What is the single most difficult challenge in revision rhinoplasty and how do you address it? During revision rhinoplasty, when dorsal augmentation is necessary and septal and ear cartilage is not available, what is the best substance for correcting the problem? If rib cartilage is used for dorsal augmentation during revision rhinoplasty, what is the technique to prevent warping of the graft? Alloplast in the nose – when, where, and for what purpose? Does the release and reduction of the upper lateral cartilages from the nasal dorsal septum always require spreader graft placement to prevent mid-one-third nasal pinching in reductive rhinoplasty?’ Analysis: Over the past 5 years, how has your technique evolved or what have you observed and learned in performing revision rhinoplasty?

Peter Adamson, Jeremy Warner, Daniel Becker, Thomas Romo, and Dean Toriumi address questions for discussion and debate:

- 1.

What is the single most difficult challenge in revision rhinoplasty and how do you address it?

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

Alloplast in the nose – when, where, and for what purpose?

- 5.

- 6.

What is the single most difficult challenge in revision rhinoplasty, and how do you address it?

Adamson and Warner

The single most difficult challenge in revision rhinoplasty is the psychology of the revision rhinoplasty patient. With respect to the psychology of the revision rhinoplasty patient, there is no doubt that the consultative process and partnership with the patient in a revision setting is vastly different from that of the primary rhinoplasty patient. While primary rhinoplasty patients are often hopeful and optimistic, the revision rhinoplasty patient is often hesitant, upset, and leery regarding what can be achieved after a failed attempt to achieve their goals. While it is important to carefully listen to patients’ concerns in any consultation, it is especially important to understand the revision rhinoplasty patient’s original concerns in addition to their current concerns. In cases where the original concerns can truly no longer be addressed adequately, it is important to be honest with the patient and tell them so. An attempt to lead the patient down a pathway likely to fail is a recipe for disaster for both the patient and the surgeon. We often would like to think we can “save the day,” but we must realize what our limits are, especially in the patient who has had 3 or more surgeries. Fortunately, in many cases, the original concerns can be addressed surgically, and it is incumbent upon the surgeon to listen to these concerns and determine what can, and what cannot, be achieved.

Iatrogenic rhinoplasty deformities can come in a variety of shapes and forms. Patient concerns may be focused on the aesthetics of the nose, function of the nose, or both. Any deformity may have an impact on the patient. The challenges for the surgeon are to determine:

- 1.

If the deformity is real or imagined

- 2.

If the surgeon has the ability to correct the deformities

- 3.

If the surgeon has the ability to achieve the patient’s original goals

- 4.

Whether or not the patient has realistic expectations coupled with the likelihood of satisfaction after surgery.

The latter is the most difficult component of the decision making process because it can be unpredictable. But we can make reasonable assumptions during the consultation process based on the patient’s personality and demeanor. The patient who understands that surgical outcomes can be partly based on nature and the healing process, and who gives the previous doctor credit for doing their best, can typically be assumed to move forward in an optimistic manner. Conversely, the patient who is very negative regarding their previous doctor, and expresses this in a revision consultation, should be considered cautiously for surgery, as they may be likely to shift their negative feelings toward the new surgeon should there be a suboptimal revision outcome.

Becker

The nationally reported revision rate for primary rhinoplasty ranges from 8% to 15%. Experienced surgeons consistently achieve a high level of satisfaction among their patients. Still, complications can and do occur despite technically well-performed surgery. All surgeons have complications.

The single most important challenge in revision rhinoplasty is to reduce the occurrence of the most commonly seen complications. On a national and international level, the most common complications that I see relate to the midnasal pyramid and lateral alar sidewalls. These complications can be reduced by recognizing this and taking steps to mitigate the risk. In both situations, the key is to ensure strong structural support. For the lateral alar sidewalls, this relates to preserving appropriate support and adding additional support as needed. In the case of the midnasal pyramid, this relates to preserving support after hump reduction. This is discussed further in the final question.

Revision rhinoplasty is a term that encompasses a wide spectrum of technical problems, from straightforward to complex. For the more complicated revision rhinoplasties, in my practice the single most difficult challenge is the psychological aspect. The revision rhinoplasty patient is someone who sought aesthetic improvement and had the opposite result. They are acutely aware of the risks of surgery, they have a strong desire for repair coupled with fear of further worsening. The challenge is to help the patient understand the realistic expectations for surgery, and to empower them to be happy after a successful surgery.

In an established revision practice, patients seeking consultation include many who have all but lost hope. Commonly, the experienced revision surgeon will find that significant improvement is possible. However, to achieve success, it is important that the patient and surgeon come to a realistic understanding of what can and cannot be accomplished. Verbal communication supplemented by computer imaging helps surgeon and patient arrive at a shared surgical goal.

The revision rhinoplasty patient needs an environment in which they will be able to develop and maintain trust. This environment is best created by dedicating oneself to revision surgery, by placing a strong emphasis on patient education, by taking the time necessary to answer the patient’s questions and concerns, and by being honest and plain-spoken. The patient must feel that the surgeon has a passion for the operation, and that the surgeon has dedicated him or herself to the pursuit of excellence in nasal surgery, and specifically revision surgery.

I have addressed this challenge by dedicating my practice to nasal surgery. I have created an atmosphere where the patient understands that they are “in the right place.” I take the extra time with these patients that they need. I include them in the process so that they are empowered.

For the most part, the surgical techniques required for a difficult rhinoplasty are available and accessible to the dedicated, experienced and skillful surgeon. This does not ensure success. The current condition of the patient’s nose may be the primary limiting factor, and it is important to educate the patient about this. Unexpected problems can be encountered during surgery as well. Ultimately, if the possibility of satisfactory improvement cannot be offered, and/or if the patient is unwilling to accept the risks that are inherent to their surgery, the patient may not be a suitable surgical candidate.

Romo

The single most difficult challenge in revision rhinoplasty is lengthening the scarred cephalically rotated, shortened nose with absence of vestibular mucosa under the upper lateral cartilages. These problems are often associated with a myriad of other nasal deformities, including internal valve collapse, external valve collapse, overresected dorsum, tip asymmetries, bossa, columella show or retraction, and alar deformities. Each of these conditions needs to be diagnosed and treated appropriately.

When patients present for an initial revision rhinoplasty consultation, a considerable amount of time – 45 minutes to 1 hour – is allowed. A thorough history of prior nasal surgery is documented. Prior treatment records are obtained if necessary. A complete physical examination of the internal and external nasal structures is completed. The deformities and problems are then documented on a template. Subsequently, a discussion with the patient commences on the philosophy, complications, benefits and possible treatment plan for the revision rhinoplasty.

Once the extent of the stenosis is determined, the treatment plan proceeds to surgical management. It is well known that lysis of stenosis with stenting using either silastic sheeting or tubing will result in restenosis once the stenting is removed. Therefore relining of the structures is required.

I perform this procedure using a full-thickness skin graft taken from the trichophytic hairline at the mastoid region. An open rhinoplasty technique is employed. The residual upper lateral cartilages are detached from the nasal dorsal septum. Scar tissue lateral to the cartilage is resected. The skin graft is inset at the dorsal septum-nasal bone interface. The skin graft is positioned so the epithelium is facing into the nasal vault. One side of the graft is sutured to the superior nasal septal mucosal line and the alternate edge of the skin graft is sutured to the mucosal lining of the released upper lateral cartilage. This continues inferiorly in a widening manner allowing for expansion of the mid- and lower one-third of the nose. This relining is carried down medially to the septal angle inferiorly and to the superior rim of the planned position of the lower lateral limb cartilage. Structural grafting of the upper lateral cartilages, dorsal augmentation, and lower lateral cartilage reconstruction can then commence. This may entail spreader grafts with caudal extension, caudal septal extension grafts, lower lateral battens, alar rim grafts and columellar augmentation ( Fig. 1 ). This structural grafting is doomed to failure unless nasal vestibular lining is replaced, thereby releasing the tethered scarred down nose.

Toriumi

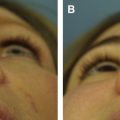

In my experience the most challenging problem in revision rhinoplasty is correction of soft tissue deformities of the nose. These include cases of skin compromise after necrosis or infection ( Fig. 2 ), severe columellar scarring ( Fig. 3 ), severe alar notching ( Fig. 4 ), and over-resection of the alar base ( Fig. 5 ). Some of these deformities are associated with the use of alloplastic implants. In such cases of soft tissue deformity it is very difficult to recreate normalcy to the nose. When addressing soft tissue deformities, damaged soft tissues may need to be replaced. Reconstruction is complicated when these soft tissue deformities are in three-dimensionally complex areas of the nose such as the soft tissue triangle or facets ( Fig. 6 A, B). These areas are very difficult to reconstruction and unfortunately are damaged or deformed from previous surgery more often than I would like to see. To correct these deformities I typically place composite skin cartilage grafts into the site of scar contracture to replace missing vestibular mucosa. This requires creative use of composite grafts taking special care to design grafts to fit the defect and also placement to maximize camouflage of the grafts (see Fig. 6 C–G). Despite placement of structural grafts and composite grafts complete correction is rarely possible. These deformities do not fall into the category of typical deformities seen in revision rhinoplasty such as the pinched nasal tip, inverted-V deformity, saddle nose deformity, polly-beak deformity, alar retraction, over-rotated nasal tip, short nose, hanging columella, and supra-alar pinching. With a normal skin envelope most of these more typical secondary deformities are readily correctable using structural grafting. However, with severe soft tissue defects it is very difficult to completely correct the deformities.