masses, with any family history of breast cancer, is thoroughly investigated.

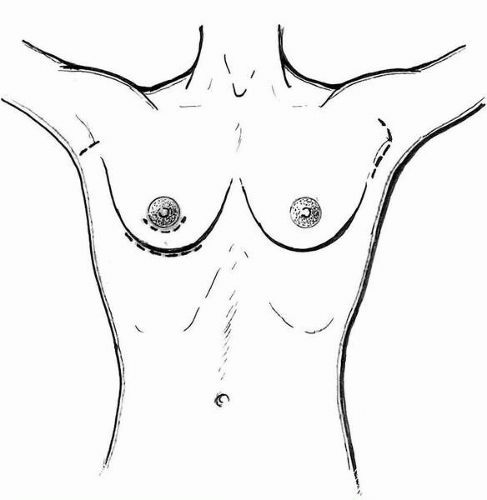

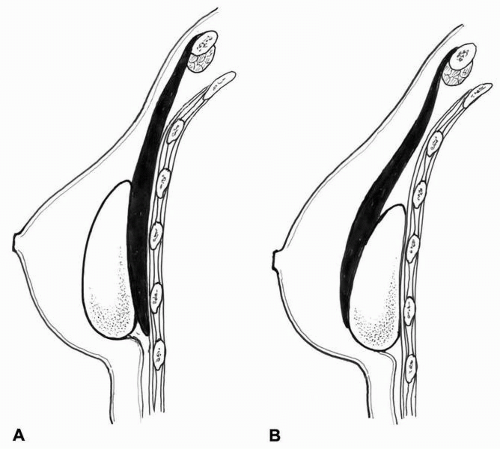

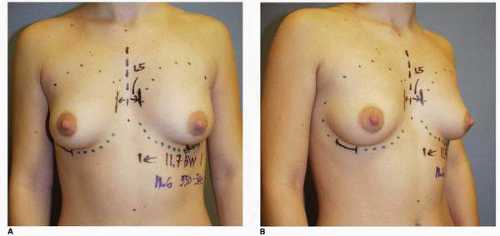

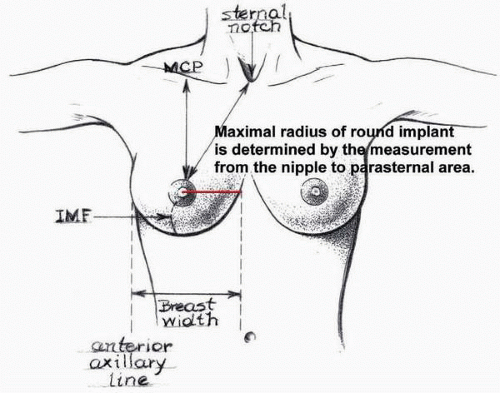

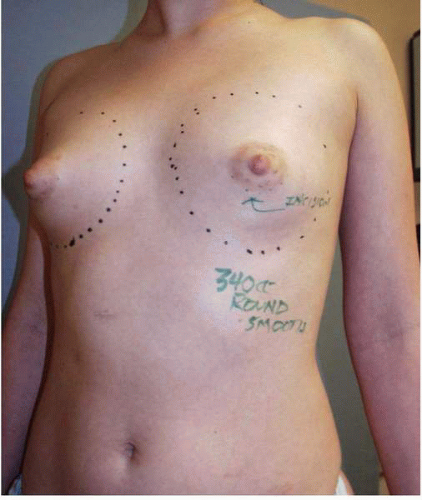

FIGURE 3-4. Measurement of nipple to parasternal area yields maximum possible radius if a round implant is selected. |

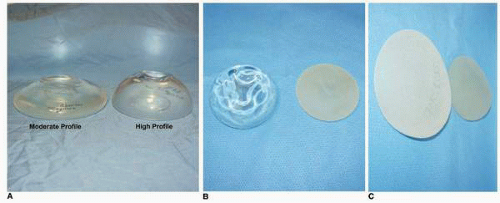

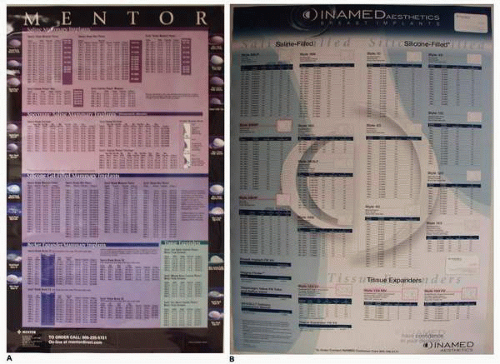

FIGURE 3-5. Charts for surface dimensions and volume of various implants manufactured by the Mentor (A) and the McGhan Corporation (B). |

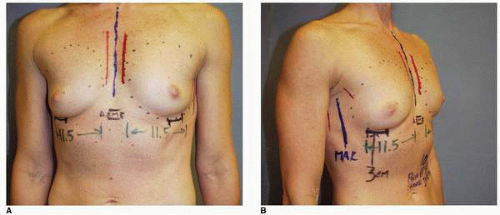

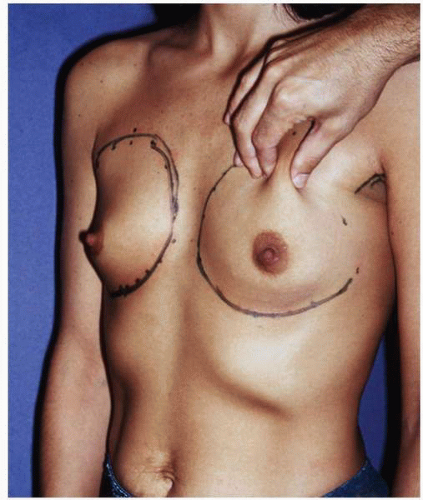

FIGURE 3-8. Pinching upper pole of the breast parenchyma is an accurate way of estimating the thickness of the breast tissue in that region. |

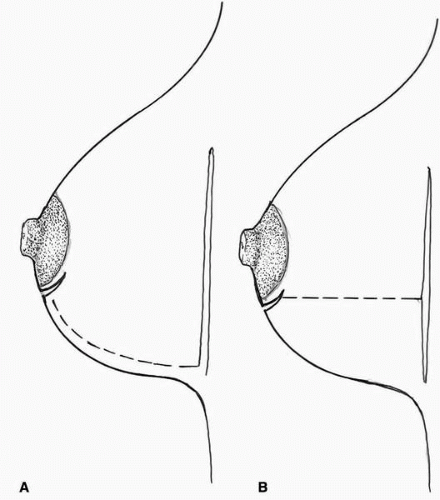

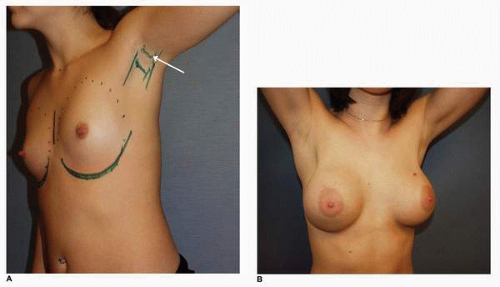

FIGURE 3-11. Constricted breast deformity (oblique view) is best approached through periareolar incision. |

lies midway between the lateral border of the PMM and the anterior edge of the latissimus dorsi muscle, which can be easily appreciated in most patients (Fig. 3-16B). I do not dissect lateral to this point. Limiting the extent of lateral pocket dissection is an important factor in limiting the likelihood of lateral implant malposition.

FIGURE 3-15. The superior extent of the patient’s breast tissue is noted by gently compressing the breast against the chest wall. |

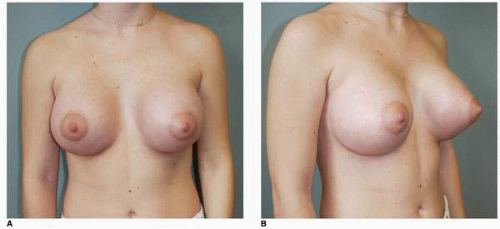

FIGURE 3-17. One-year postoperative AP (A) and oblique (B) views of the patient noted in Figure 3-14. |

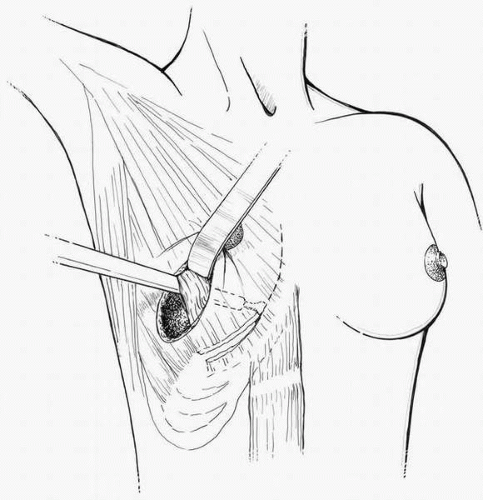

FIGURE 3-18. Lateral dissection is performed with gentle digital dissection to maximally preserve the sensory nerves to the nipple. |

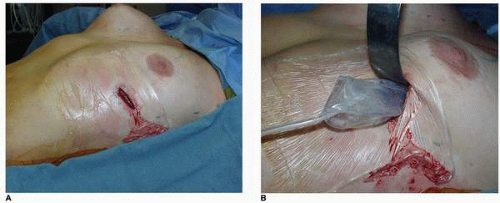

FIGURE 3-20. A, Sterile OpSite barrier drape is placed over the incision on patient’s skin before implant insertion. B, The implant is inserted through an opening in the barrier drape. |

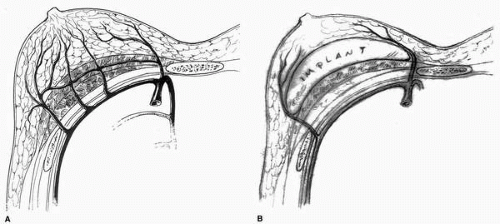

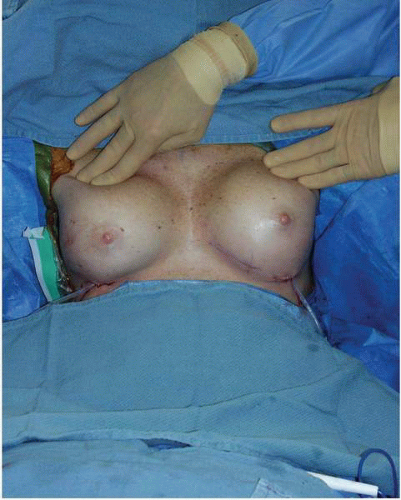

cavity. I have found that a sample sizing implant works equally well for this maneuver. Next the endoscope is inserted, and operating through the same transaxillary incision the origin of the PMM is visualized (Fig. 3-22B). This technique provides a controlled release of the muscle (Fig. 3-22C) and can also facilitate hemostasis. The final inferior dissection to establish the inferior aspect of the implant pocket is done with the Agris-Dingman dissector. After completing the dissection of both pockets, the space is irrigated with a solution containing 50,000 IU of bacitracin, 500 cc cefazolin (Ancef), and 80 cc gentamicin in 1,000 cc of sterile saline IV fluid27 and the sample sizing implants are placed. Symmetry between the breasts is checked with the patient in the sitting position. I find that it is helpful to gently compress the upper poles of the sizers to ensure symmetry of the lower aspect of the breasts (see Fig. 3-19). When the appearance of the breasts is completely satisfactory, the implants are inserted and the axillary incision is closed in two layers, including the deep dermis and skin wound. I prefer to approximate the skin incision with 5-0 nylon sutures. A similar dressing to that described earlier is placed.

treatment is to maximize the mobility of the implant and the distensibility of the periprosthetic capsule. I personally believe that this maneuver helps keep the implant as soft as possible, and it may limit the occurrence or extent of capsular contracture. This opinion is shared by many plastic surgeons.29,30 More important, this maneuver is something that the patient can do to help her recovery and preserve the softness and natural feel of her result.

complications. This will build the best possible doctor-patient relationship that I find so helpful during the recovery from additional surgery—especially if there are additional complications.

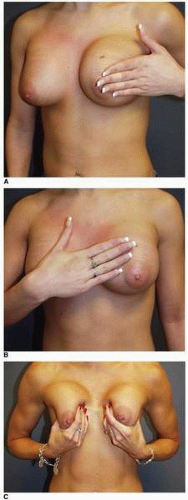

FIGURE 3-23. Implant displacement exercises following breast augmentation. A, Medial displacement. B, Lateral displacement. C, Vigorous superior displacement may also be helpful. |

TABLE 3-1 Overview of Reoperative Breast Augmentation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

particular positions that bother the patient, specific descriptions of these circumstances should be elucidated. Is there pain or discomfort in the breast(s)? The etiology of such breast pain or mastodynia in the setting of a previous breast augmentation is often difficult to establish and most of the time is multifactorial. I most often tell the patient that there is no surgical solution or surgical cure for breast pain. Has there been a change in the appearance of the breast, and if so what is the time course of the change? Is there a history of previous implant rupture or deflation of a breast implant, and if so how was that problem treated?

commonly noted abnormality early on after breast augmentation. From my perspective, in these situations there is little concern that the implant will descend to the appropriate level if the implant was noted to be in the appropriate position at the completion of the operation. Most often the implant will settle into a lower position as the pectoralis major muscle stretches out during the first 4 months following surgery. However, if significant malposition of the implant in a medial, lateral, or inferior location is present at 3 months following surgery, it can lead to a permanent breast asymmetry or deformities that very well might represent an indication for revisional surgery on the breast(s) later in the postoperative course. Additional surgical or technique-related complications are decreased nipple sensibility; breast asymmetry; implant edge palpability; and the presence of ripples, ridges, or folds that can be seen through the skin. The latter three conditions are noted if the dimensions of pocket dissection is inappropriate—either too large or too small.

FIGURE 3-24. The typical appearance of superficial thrombophlebitis in the axillary veins. Note cord below skin. |

FIGURE 3-26. A hematoma in the right breast following a partial subpectoral breast augmentation seen on postoperative day 6. Note ecchymosis and size difference between the breasts. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree