Repair of Flank and Lumbar Defects

Sergey Y. Turin

Chad A. Purnell

Gregory A. Dumanian

DEFINITION

A defect in the flank/lumbar region of the abdominal wall can be a challenging problem as there is much discord in the literature regarding its etiology and management. Defined as an inability of the abdominal wall to properly contain the viscera and located lateral to the semilunar line, flank defects are encountered after surgeries requiring retroperitoneal access (transplant, vascular, urologic); these defects occurred fairly frequently, ranging from as low as 8% to 23% in the literature.1,2,3,4 The etiology of these defects can be of two types—a hernia or a focal weakness of the abdominal wall, usually attributed to denervation injury. A true hernia implies violation of one or more of the layers of the abdominal wall musculature. In contrast, a bulge secondary to denervation injury leading to muscle attenuation and weakness implies continuity of all three layers of the abdominal wall. In our recent review of 31 patients, we found that 55% of patients had a disruption of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, whereas the external oblique muscle was intact—a type of “partial” hernia often confused with a denervation bulge. In 32%, all three abdominal wall layers were disrupted as true incisional hernias. In the remainder, the three layers of the abdominal wall were intact but had a loss of tone due to denervation— true abdominal wall bulges.

We present a reliable technique to repair the flank defects that is efficacious for true hernias and can be used for certain denervation injuries.

ANATOMY

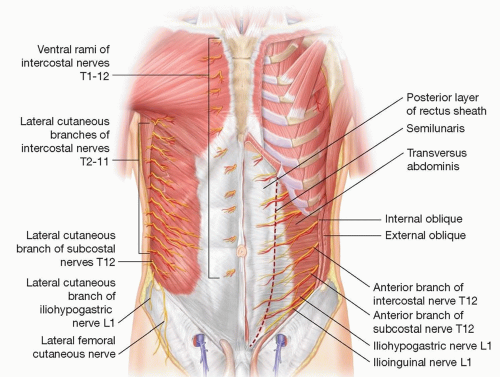

The lateral and lumbar abdominal wall is composed of three load-bearing muscular layers and their respective fascial envelopes—the external and internal oblique and the transversus abdominis. All three of these can be compromised by an incision for retroperitoneal access. Discontinuity of these layers would lead to a hernia defect. (See the chapter on “Synthetic and Biologic Mesh for Abdominal Wall Defects,” FIG 1, for example.)

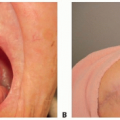

The muscles of the abdominal wall are segmentally innervated by the 7th through 12th intercostal as well as the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves running between the transversus abdominis and the internal oblique muscles. In this plane, they are vulnerable to transection during a retroperitoneal approach for incisions that cross dermatomes. They are also susceptible to focal injuries from retractors, cautery, and abdominal wall full-thickness sutures (FIG 1).

PATHOGENESIS

True hernias occur when the ultimate tensile strength of the repair is less than the forces applied. Acutely, the sutures can tear through the abdominal muscles during coughs and forceful movements and lead to a dehiscence or evisceration. Chronically, tissue located within the loop of suture becomes scar. When the strength of the scar, sutures, and foreign body reaction to those sutures is less than the forces applied, an incisional hernia develops. In comparison to incisional hernias, flank bulges are due to denervation of the abdominal wall. Narrow zones of denervation with loss of just one or two intercostal nerves during the original surgery do exist, often due to resection of spinal cord roots for exposure or tumors. Alternatively, there can be a large zone of denervation from a profound spinal injury. The larger the zone of injury, such as with a spinal cord injury, the less the techniques in this chapter apply.

With maneuvers that are intended to stabilize the torso such as the Valsalva maneuver, the viscera instead distend the flank defect and cause a disagreeable and sometimes painful contour irregularity. Patients complain of discomfort due to an inability to raise their intra-abdominal pressure and altered torso mechanics—a loss of “core strength.”

See the chapter on “Abdominal Hernia Reconstruction” for a discussion of the biomechanics of the abdominal wall and the importance of evaluating abdominal wall compliance when dealing with these defects.

NATURAL HISTORY

These defects can often be a cause of marked pain and lead to functional impairment with diminished quality of life.5 The plastic surgeon will usually see the patient in a delayed setting, with the consultation being prompted by worsening symptoms.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients are encouraged to obtain all the previous operative notes, and it is important to record if a rib was resected at the original procedure. Hernias present for many years are more difficult to close than a hernia less than 1 year from the index surgery. It is of great importance to discuss the medical history and comorbid conditions, such as COPD, diabetes, cardiac disease, and any rheumatoid conditions.

Prior incisions are recorded, and an evaluation of skin quality and abdominal wall compliance is made. The patient is asked to stand as well as to lie in the lateral decubitus position to clarify the borders and size of the defect. Palpate the bulge with an eye toward feeling any muscle contraction or edge to the defect to gain an idea of whether the remaining muscle is innervated and continuous. Look for incisions of the midline back that denote spine pathology and possible denervation.

A social history is important to appreciate the stresses on the torso required to return to work or important social activities.

IMAGING

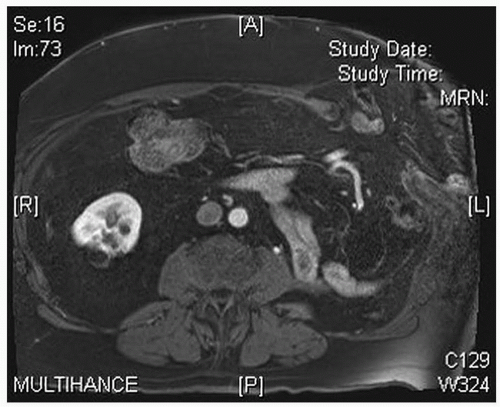

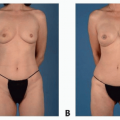

We routinely obtain a CT scan of the abdomen using oral and IV contrast to assess the layers of the abdominal wall, to measure the size of the defect, and to screen for any other intra-abdominal pathology (such as a recurrent cancer) as dictated by the patient’s history. Any midline hernias would be documented (though typically not addressed) at the time of the flank repair (FIG 2).

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

If there is adequate soft tissue coverage over the viscera, we counsel the patient that closure of these large defects is indicated if they are symptomatic and the hernia affects their lifestyle and activities. Given the usually large size of these hernias, bowel incarceration is infrequent. Nonoperative management with binders or fajas is encouraged, but typically is only partially effective, and patients typically do not feel comfortable in these hot and heavy garments. Patients with significant medical problems and patients with large zones of denervation are often encouraged not to have repair in an effort to balance risks and benefits of the procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree