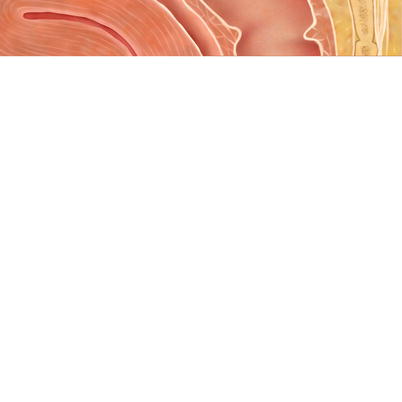

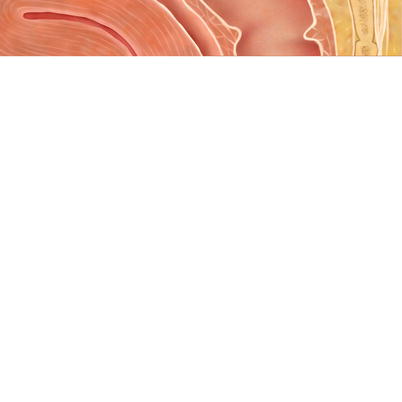

Fig. 38.1

(a) Creation of an endorectal advancement flap and closure of the rectal opening. (b) Covering the internal opening of the fistula with the flap

With this approach, Rothenberger and colleagues [37] reported a success rate of 86 % with the endorectal advancement flap as early as 1982. The same group has analyzed the correlation between their success rate and previous repairs and found a decreased success rate in repeat repairs. Successful repair was achieved in 88 % at the first attempt, 85 % with a history of one prior repair, and 55 % with a history of two previous attempts [38]. Kodner and colleagues [39] reported in 1993 a large series of 71 patients with rectovaginal fistula who underwent repair with an endorectal advancement flap, with good results. All of those who had failed the initial procedure underwent repeat endorectal advancement flap, resulting in complete healing of the fistula in all cases. Hull and Fazio [40] reported a series of 35 patients, all with Crohn’s disease, who had undergone rectal advancement flap for rectovaginal fistula. The success rate of the initial procedure was 54 %, and in five patients in whom the procedure had failed, a repeat endorectal advancement flap was successfully performed. Mizrahi et al. [41] reported a series of 106 patients who had undergone endorectal advancement flap for complex perianal fistulas, of whom 32 had rectovaginal and 5 pouch-vaginal fistulae. Long-term success for the rectovaginal fistulae was achieved in 66 % of the patients compared with 60 % in the entire series. Nearly half of the patients in this study had some kind of previous attempt at repair, ten of whom had undergone an endorectal advancement flap. The success rate in patients with a previous repair was 74 % and, specifically, eight of the ten patients who had undergone repeat advancement flap had a successful outcome. These results, however, relate to all types of anorectal fistulae and subgrouping of rectovaginal fistulae was not specifically examined. Recently, de Parades et al. [42] have suggested the addition of a muscular plication before coverage of the repaired internal opening by the flap. In their series, 9 of the 23 patients had prior failed attempts. Complete cure was achieved in 65 % of the patients.

Recently, repair techniques utilizing biologic materials into the fistula tract have been developed. In these techniques, no tissue dissection is required and there is minimal risk of complications. Biologic materials are acellular matrices that promote migration of inflammatory cells into the matrix, leading to wound healing and resulting in permanent obliteration of the fistula tract. Initially, the use of fibrin glue was attempted. Fibrin glue is a blood product that uses the activation of thrombin to form a fibrin clot, mechanically sealing the fistula tract. The clot promotes tissue healing while being gradually absorbed by fibrinolysis. However, this technique seems to be more successful in long and narrow fistula tracts, such as those crossing through the perineal body between the anal canal and the vaginal opening, and is less appropriate for the short fistulae typically located in the rectovaginal septum. Reports of the use of fibrin glue for the indication of rectovaginal fistula are sporadic. Loungnarath and colleagues [43] attempted this repair in three patients, one of which was successful. Newer biologic substances include the collagen plug. This collagen acellular matrix forms a semirigid cylindrical plug that is deployed into the fistula tract. To prevent migration of the plug, especially in short fistula tracts, a plug attached to a fixation button also is available. Using this plug, which is available in several sizes for different fistula widths, the fistula tract is first probed throughout its length and cleaned using a commercially available pipe cleaner brush. The collagen plug is then transanally inserted and pulled into the fistula tract from the rectal opening to the vaginal one until the fixation button reaches the rectal wall. The button is than secured to the rectum using several absorbable sutures. Excess length of the plug may be trimmed on the vaginal side and the plug may be loosely secured to the vaginal side with an additional absorbable suture (Fig.38.2). The plug is gradually absorbed by an inflammatory process and replaced by scar tissue, and once the stitches used to secure the button are absorbed, the button falls out and is expelled with a bowel movement.

Fig. 38.2

Rectovaginal collagen plug with button (Permission for use granted by Cook Medical Incorporated, Bloomington, Indiana)

Thekkinkattil et al. [44] reported ten patients with rectovaginal or pouch-vaginal fistulae treated with collagen plugs without a button. Fistula healing was achieved in only two patients compared with a 50 % success rate in patients with perianal fistulae not involving the vagina. Ellis [45] treated seven patients with rectovaginal fistulae using the collagen plug without the button, five of whom had Crohn’s disease. In all cases, this was the first attempt at repair. In six patients the fistula healed and only one suffered recurrence. Gonsalves and colleagues [46] performed 20 fistula repairs using the buttoned plug in 12 female patients, 7 of whom had pouch-vaginal fistulas. Of these 12 patients, 5 had previous surgical repairs, including 3 with the nonbuttoned plug. Successful repair was achieved in 7 of the patients (58 %), resulting in a success rate of 35 % with all plugs used. Of interest, only one of six patients who had a second plug inserted healed successfully, and neither of the two patients who had a third attempt had a successful outcome, suggesting that the chance of repeat insertions is lower if the first insertion failed. Recent results by Lupinacci et al. [47] were poor in 15 cases, 7 of which had undergone prior repairs, with a moderate expulsion rate of the anal fistula plug in this series.

Vaginal Repairs

Repair of a rectovaginal fistula using the vaginal approach allows easy access to and a superior view of the vaginal opening of the fistula. This approach usually allows easier access to the fistula tract in comparison with the transanal operation, although there is a potential disadvantage of repair of the fistula from the lower pressure side. This approach seems to be less commonly used by colorectal surgeons. Several surgical techniques have been described for the transvaginal repair. Most often, the procedure involves the creation of a vaginal wall flap, dissection in the rectovaginal septum below the flap to divide the fistula tract, repair of both sides of the fistula, and suture of the vaginal flap again over the repair of the tract. An adjunct to this technique may be the use of absorbable or biologic mesh, which can be interposed between the rectum and the vagina to reinforce the rectovaginal septum before closure of the flap to enhance the formation of scar tissue and to bolster the deficient perineal body (Fig.38.3a, b).

Fig. 38.3

Transvaginal repair with biologic mesh. (a) Creation of the flap using a vaginal approach. (b) Placement of the biologic mesh

Bauer et al. [48] used the vaginal approach for low or mid rectovaginal fistulae in 13 patients with Crohn’s disease, 12 of whom successfully healed. Importantly, all patients in this series had temporary diversion either before or concomitantly with the repair. Casadesus et al. [49] used the same approach in 12 patients with fistulae of various etiologies, 9 of whom successfully healed. One of the patients with a failed repair underwent repeat repair using the vaginal approach, which failed again. Ruffolo et al. [50] reported a systematic review comparing the success rate of transvaginal repair with transanal advancement flaps in patients with Crohn’s disease. The fistula healed in 54 % of the patients who had undergone a transanal repair compared with 69 % in those undergoing transvaginal repair, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Perineal Approach

The perineal approach for the repair of rectovaginal fistula involves a perineal skin incision, cephalad division of the rectovaginal septum to separate the fistula tract, repair of both sides of the fistula, and interposition between the rectum and the vagina. Traditionally, such interposition should be performed with well-vascularized, fresh, noninflamed, and nonirradiated tissue, which may include labial fat tissue, a pedicled muscular graft, and, recently, biologic mesh.

The Martius graft is made of labial fat tissue rotated into the space created between the rectum and the vagina. In this procedure, an elliptical incision is made over the labia majora and the flap is mobilized and separated from adjacent structures, preserving the posterolateral pedicle. It is then tunneled beneath the vaginal mucosa and labia minora to overlie the closure in the rectum and the vagina. Such a procedure may be more appropriate for the treatment of fistulae in the lower part of the rectovaginal septum, where such a flap can easily be interposed without tension. An example of a Martius graft for a cryptogenic fistula is shown in Fig.38.4a–c.

Fig. 38.4

Martius bulbospongiosus graft in cryptogenic rectovaginal fistula. (a) Lockhart-Mummery probe is placed into the rectovaginal fistula. (b) Redirection of the probe through the perineum after vaginal repair. (c) Bulbospongiosus (Martius) graft fashioned for rectovaginal interposition (Figures courtesy of A.P. Zbar)

McNevin and colleagues [51] reviewed their experience in 16 patients in whom the rectovaginal fistula was repaired using a Martius flap. In most of these patients, the fistula was the result of obstetric injury. Several of these patients had undergone previous repairs using a rectal mucosal advancement flap, local transvaginal repair, and a lay open repair. In this study, six patients were diverted at the time of the Martius flap repair. The fistula healed successfully in all but one patient, although, importantly, five patients complained of postoperative dyspareunia. Songne et al. [52] reported their experience with the Martius flap repair in 14 patients with rectovaginal fistula, half of whom had Crohn’s disease and 4 of whom had a pouch-vaginal fistula. In all 14 cases, the fistula completely healed by 3 months of follow-up. In two cases, however, recurrent, aggressive perianal Crohn’s disease required subsequent proctectomy.

Several muscular interposition flaps had been used for the repair of rectovaginal fistula, of which the gracilis muscle seems to be the most common. Harvesting of the gracilis muscle may include two to three 3- to 5-cm-long incisions alongside the inner part of the thigh over the gracilis muscle. Tunnels are made between the incisions in the subcutaneous tissue overlying the muscle, and the muscle is dissected throughout its length (Fig.38.5a–e). The most proximal incision is situated approximately one hand’s breadth beneath the inguinal ligament to allow adequate exposure of the neurovascular bundle. The gracilis muscle is disconnected from its insertion near the tibial plateau and then is dissected free and delivered through the proximal incision. Care should be taken to identify and preserve the neurovascular bundle. A subcutaneous tunnel is then made through the proximal thigh incision rostrally toward the perineum, and the muscle is placed in the pocket proximal to the upper incision.

Fig. 38.5

Gracilis muscle transposition. (a) location of thigh skin incisions. (b) Muscle dissection. (c) The neurovascular bundle. (d) location of perineal skin incision. (e) The muscle is brought to interpose between the rectum and the urethra or the vagina

The perineal dissection is then carried out. Such an approach may be used in an exaggerated litothomy position or in the prone jack-knife position. In our experience, the prone jack-knife position provides a superb view of the anterior wall of the rectum, an excellent view of the perineal dissection plane between the rectum and the vagina, and easy access for adequate repair of the fistula openings and fixation of the interposed muscle. An incision is made in the perineun anterior to the anus, about halfway between the anus and the posterior border of the vaginal opening. The dissection is then undertaken at the rectovaginal septum to divide the fistula tract and reaches cephalad to noninflamed tissue. In cases of recurrent rectovaginal fistula, or when there is a history of surgery violating the rectovaginal septum (such as a coloanal or ileoanal anastomosis), redissection of this septum may be difficult because the surgical planes are fibrotic, nonareolar, and nonpliable. Care should be taken to identify the correct plane and avoid a repeat injury to the rectum and vagina during dissection. Dissection of the fat tissue lateral to the rectovaginal septum bilaterally may sometimes assist in the identification of the correct plane. The rectal defect then is closed primarily or with an advancement flap. The subcutaneous tunnel between the perineum and the thigh is approached through the perineal incision until the pocket where the gracilis muscle has been placed is reached. The gracilis muscle is rotated and gently brought through the perineal incision. Care should be taken to avoid excessive tension on the neurovascular bundle and to prevent any compromise of the blood supply. The gracilis muscle then is brought to the previously dissected perineal space and placed to interpose between the rectum and the vagina. Four to six sutures are applied to the muscle and the apex of the incision to hold the muscle in place.

Rius et al. [53] reported 17 patients with a fistula between the rectum and the vagina, 3 of which occurred after an ileoanal or coloanal anastomosis. In nine patients, the fistula was associated with Crohn’s disease. Seventy-six percent of the patients with a pouch-vaginal fistula had undergone a mean of two prior failed attempts at repair. The rectovaginal fistula healed in 75 % of the patients without Crohn’s disease compared with only 33 % in Crohn’s fistulas. Of note, two patients required a second gracilis transposition. Ulrich et al. [54] reported nine patients with rectovaginal fistula (three of whom had Crohn’s disease) who underwent gracilis interposition. Two of the patients with Crohn’s disease had a recurrent fistula, whereas all patients without Crohn’s disease completely healed. Fürst et al. [55] reported 12 patients with rectovaginal fistula scondary to Crohn’s disease, with only one failure. One patient with a pouch-vaginal fistula required a second gracilis transposition to heal. Recently, Lefèvre and colleagues [56] reported eight patients with rectovaginal fistulas, six of whom successfully healed with gracilis transposition. The two patients who failed underwent a second gracilis transposition, which was unsuccessful in both cases. This approach recently has been reported to be highly successful in a range of rectovaginal fistulae after pelvic surgery for pelvic malignancy [57].

Recently, the use of biologic mesh to interpose between the rectum and the vagina has been suggested. The mesh is placed in the rectovaginal space after completion of adequate dissection of the rectovaginal septum and repair of both openings. Although not a vascularized graft, these meshes are made of acellular collagen matrices, into which inflammatory cells migrate to form scar tissue and fibrosis while the mesh is gradually absorbed. The use of these newly introduced meshes may avoid the need to create a muscular or fat pad flap, which may be associated with significant local morbidity. In this respect, Ellis [45] used collagen mesh in 27 patients, 14 of whom (52 %) had prior attempts at repair. Only two of these patients suffered from Crohn’s disease, and the reported success rate was 81 %. Shelton and Welton [58] used dermal collagen mesh (AlloDerm) in two cases, both of which had a successful outcome.

Abdominal Repairs

The abdominal approach for the repair of rectovaginal fistula involves a major laparotomy and deep anterior pelvic dissection to divide the fistula tract. The lower the fistula, the deeper the pelvic dissection required. In some cases, repair of both sides of the fistula and interposition with an omental flap may be possible. In several cases, however, especially when the fistula results from a circular anastomosis or is associated with radiation therapy, the affected rectal or neorectal segment may need to be resected, with the creation of a new lower anastomosis. The obvious disadvantage of this procedure is the magnitude of the surgical trauma and its associated risks. In addition, this approach may be challenging in patients with previous abdominal surgeries, and the omentum may not be available for use as an interposition flap.

Nowacki [59] used the abdominal approach with a coloanal sleeve anastomosis in 24 patients with rectovaginal fistula after radiation. There was one postoperative death and 18 of the remaining 23 patients had asuccessful outcome. Cooke and Wellsted [60] reported a 93 % success rate in 55 patients who had received radiotherapy and underwent resection and coloanal anastomosis. This technique also has been reported recently by Schouten and Oom [61] from the Netherlands in eight patients, with a successful outcome in five in whom a rectal sleeve advancement was employed via a posterior Kraske or abdomino-Kraske (Localio) approach.

Consideration and Selection of Procedure

Repair of a rectovaginal fistula is a challenging surgical task and associated with a significant failure rate, irrespective of the operative method. For this reason, patients with a rectovaginal fistula who had failed one or more previous attempts at repair are not infrequently encountered. In addition to the complexity defined by the fistula etiology, such as Crohn’s disease or radiotherapy, previous surgical repair may further complicate future attempts, obscuring anatomic planes and inducing extensive scar tissue. Despite this, repeat repairs are usually possible and are often successful. Halverson et al. [62] reported 35 patients who had 57 repairs of recurrent rectovaginal fistulae using various methods of repair. Seventy-nine percent eventually healed after a median of two operations. MacRae et al. [63] reviewed 28 patients who underwent repair of recurrent rectovaginal fistulae, with a 61 % success rate. The fistula successfully healed in 72 % of the patients with fistulae defined as simple compared with only 40 % of those with fistulae defined as complex.

As for the selection of the procedure, all of the above-mentioned surgical techniques for the repair of rectovaginal fistula also are viable for the repair of recurrent cases, and there are no strict guidelines to determine which procedure is best for the next attempt. Basically, there are three main options: to repeat a procedure that already has been attempted, to scale up to a more extensive procedure, or to scale down to a less extensive operation. The literature regarding the proper selection of procedure for reoperative rectovaginal fistula is limited, as is the number of recurrent fistulae after failed surgery in most series. Several case series dealing with procedures such as the endorectal advancement flap [41] and gracilis transposition [53] suggest that a second attempt with the same procedure carries a similar success rate as the first round, whereas series dealing with the instillation of biologic substances suggest that repeat procedures have a lower rate of success compared with the first attempt [46]. The role of sporadically reported techniques including the use of cyanocrylate [64], episioproctotomy as part of definitive repair [65], laparoscopic approaches [66], or novel vascularized flaps used for congenital conditions in children [67 68] are not sufficiently mature to render informed comment. In specific cases for which reinforcement meshes have been used in prior pelvic surgery, early evidence would suggest that the prosthetic material needs to be removed with coincident omental interposition [69].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree