Breast-conserving therapy is currently the most common method of treating patients with breast cancer. The efficiency and validity of such treatment have been established by many large prospective studies [National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) and World Health Organization (WHO)] that have identified the equivalence of survival in patients so treated when compared with those treated with standard modified radical mastectomy.

1,

2 and

3 The treatment entails removing a breast cancer with a surrounding rim of normal breast tissue with the subsequent provision of adjuvant radiation to the remaining breast parenchyma. This treatment preserves most of the patient’s breast while accomplishing resection and local control of the patient’s breast cancer. This breast-conserving treatment carries with it a 1% per year risk of local recurrence, but the survival rates of patients treated in this way are equivalent to those of patients treated with mastectomy over 15 years of follow-up.

1,

2,

3 and

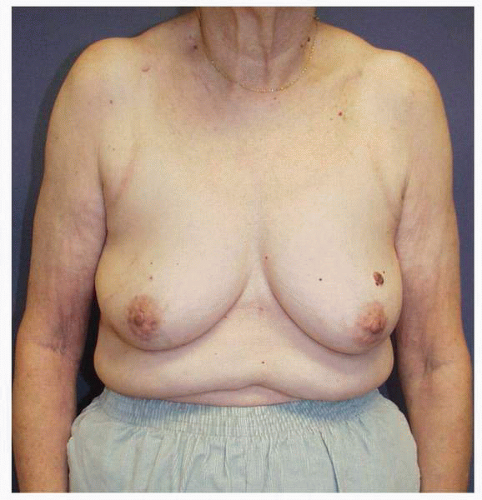

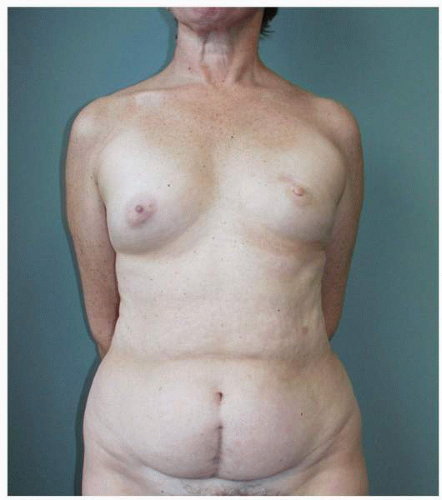

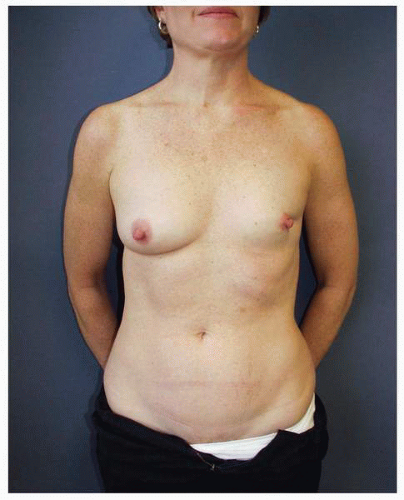

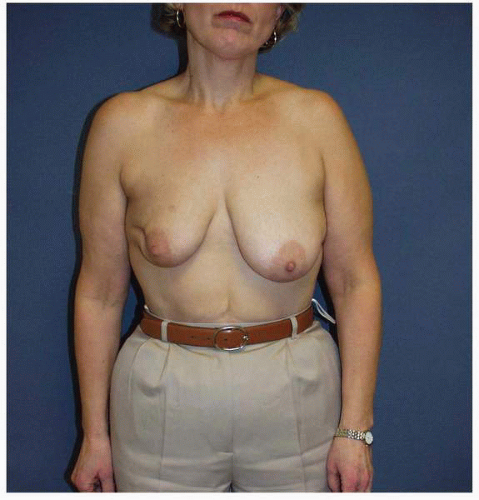

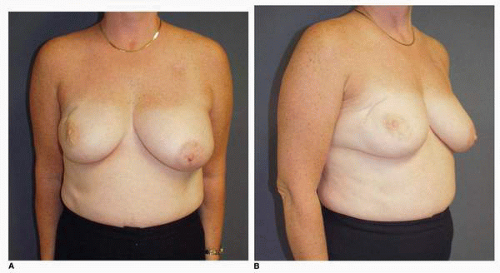

4I have come to understand this surgery not only an oncologic surgical procedure but also as a cosmetic operation. That is to say, it is generally good to preserve a woman’s breast when treating a breast cancer. However, this is only true if such treatment results in a breast that is not deformed by such treatment and that a woman believes is worth keeping or preserving (

Figs. 9-1,

9-2 and

9-3).

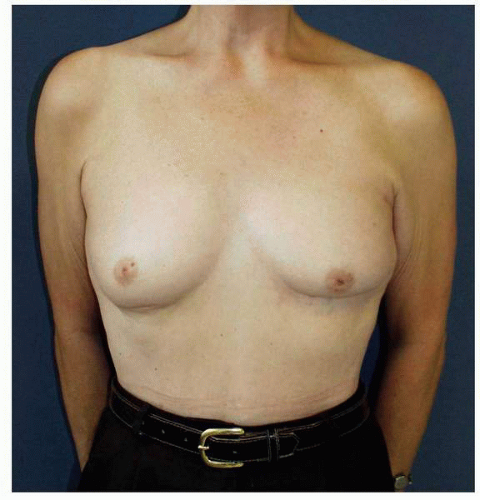

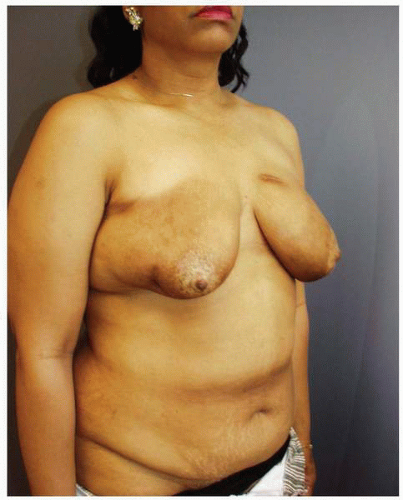

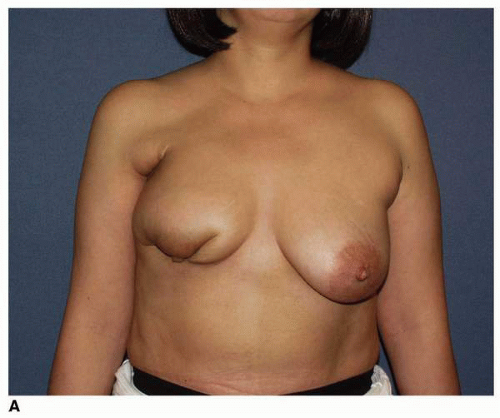

Obviously any operation that removes tissue from the breast through a surgical incision with the subsequent addition of radiation therapy virtually always alters the breast. These changes involve every anatomic component of the breast gland. There are changes in the skin pigmentation, elasticity, and thickness. In addition, there are often alterations of breast volume and contour and position of the nipple areolar complex (NAC;

Figs. 9-4,

9-5,

9-6,

9-7 and

9-8).

As the prevalence of this technique has increased, many experienced general and oncologic surgeons have become increasingly aware of which breast cancer patients are candidates for such procedures and which are not, from the standpoint of the resulting breast cosmesis. I believe that it is critical to select this option only in those patients who are likely to achieve a satisfactory cosmetic outcome.

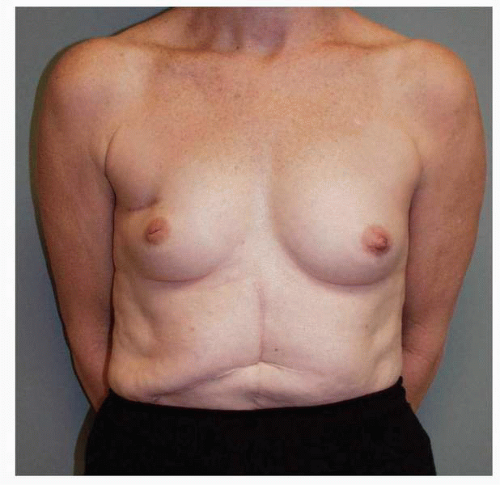

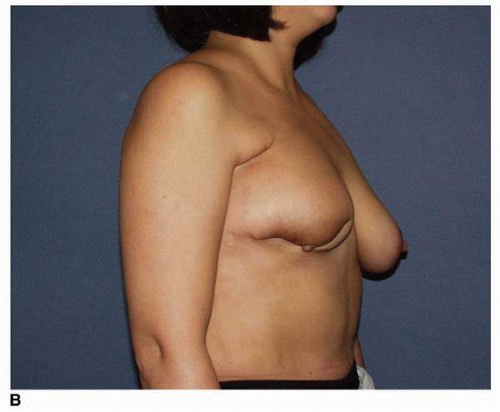

Factors that are predictive of poor results are a large tumor size relative to total breast size (large tumor in small breast) (

Fig. 9-9) and tumor location relative to NAC (tumors immediately superior to or inferior to the NAC cause more displacement of the nipple following treatment;

Fig. 9-10). Additionally, patients who require reexcision after the first attempt at resection and those developing wound problems, most notably infection, very often show a poor cosmetic outcome. Patients such as these are many times better off undergoing a mastectomy and having an immediate breast reconstruction.

An early question was whether the surgical tumor excision or the adjuvant radiation therapy was more of a factor in the production a poor outcome. This question was analyzed by Matory et al.,

5 who verified that it was the volume of breast parenchymal resection relative to total breast volume that was the most influential determining factor in the genesis of the significant postlumpectomy

and radiation deformity. Radiation plays a role due to its qualitative effect on the breast skin and remaining breast parenchyma, but its effect is less significant than that of surgical excision. In that same review, a comparison was made of patients’, surgical oncologists’, radiation therapists’, and plastic surgeons’ assessments of the overall cosmesis using a scale of 1 to 10. The patients themselves scored their own breast cosmesis most favorably. The cosmetic outcome was scored with decreasing appeal by the radiation therapists, surgical oncologists, and plastic surgeons, with the plastic surgeons issuing the lowest scores for the quality of cosmetic outcome.

Several things are clear at the time of this writing. More and more patients are being treated for breast cancer with breast-conserving therapy (i.e., lumpectomy and radiation therapy). As a consequence, more and more patients are being seen by plastic surgeons for treatment of postlumpectomy deformities that have resulted in objectionable breast asymmetries. I personally continue to see an ever increasing number of patients requesting correction of postlumpectomy deformities. Some of these patients have presented after a second and sometimes even a third excision that has been done to obtain a tumor-free

margin. Some patients probably were not optimal candidates for the procedure in the first place but were disinclined to have a mastectomy. From my discussions with these patients it appears that many of them had an unrealistic expectation regarding the outcome of such treatment.

I believe that general surgeons with whom I work closely and who focus their practice on breast oncology do a good job of selecting the patients who will not obtain a good result from such treatment and steer such patients in the appropriate direction of mastectomy. Nevertheless, there are increasing numbers of patients who are presenting to plastic surgeons around the world with significant deformities of their breasts following lumpectomy and breast irradiation. Such problems vary both in their severity and in their contributing components. Because of this it follows that successful treatment from the standpoint of improving breast appearance requires a careful analysis of each breast deformity with an individualized treatment plan devised based on the patient’s chief complaint and the surgeon’s physical examination of the breast(s).

This chapter overviews treatment options for the most commonly presenting breast problems following lumpectomy and radiation therapy for breast cancer. The treatment options for postlumpectomy deformity are outlined in

Table 9-1.

PLASTIC SURGERY RECONSTRUCTION OF THE LUMPECTOMY DEFECT

Patients seek reoperative breast surgery following a previous lumpectomy because of either breast asymmetry, with an acceptable appearance of the breast that has undergone a breast-conserving procedure, or a deformity of the ipsilateral breast that has undergone the tumor removal and radiation therapy. Such deformities requiring surgical reoperation for reconstruction are either moderate to significant in their severity, and their correction may or may not entail an adjustment of the opposite breast to optimize symmetry. Moderate defects require reconstruction methods that entail local tissue rearrangements, occasionally the placement of an implant and often the provision of a musculocutaneous flap or free tissue transfer. Patients with an acceptable appearance of their ipsilateral breast are often best treated with an adjustment of the opposite breast in the form of a mammoplasty procedure.

THE POSTLUMPECTOMY DEFECT

Postlumpectomy defects most often pose a significant challenge for the plastic surgeon. What makes them difficult is that there is almost always a tissue deficit with

varying degrees of intraparenchymal fibrosis or cicatrix and skin scarring, along with a global hypovascularity of breast due to radiation. The degree of quantitative skin deficiency varies, but there is always a qualitative skin abnormality. Very often there is an element of nipple areola displacement or dislocation in cases of larger skin resection or significant parenchymal tissue resection, with a corresponding contour abnormality of the breast. Surgery on the postlumpectomy defect, by definition, is always revisional or reoperative in nature.

The goals for treating postlumpectomy deformity are similar to those espoused in the previous chapters of this text. They are restoring symmetry by reconstructing contour deficits and correcting tissue deficits in kind, with the overall goal of restoring breast appearance as much as possible to what the eye would see and the brain would recognize as normal. There are additional constraints in treating postlumpectomy deformity that are imposed by the combination of radiation and scar effects from the previous surgery(ies), and these must be outlined for each patient by the surgeon preoperatively.

The important principles at play in reoperative surgery in this group of patients are the same as those in the treatment of every secondary defect. These include recreating the deformity by releasing and resecting all scars, and then reconstructing the defect. The defect resulting from the intraparenchymal scar almost always requires some sort of reconstruction procedure. This may entail repositioning of the residual breast pedicle and/or reshaping the skin envelope of the ipsilateral breast, a partial reconstruction of the breast with the addition of flap tissue, completion of the mastectomy, and a reconstruction of an entirely new breast.

It has been my experience that in most instances the ideal reconstructive medium is vascularized tissue, which brings in a new blood supply that can produce neovascu-larization of the wound. Although the volume deficit is a primary component in the genesis of the problem, an implant alone is rarely the answer.

5 Both modalities can be used, as is illustrated later in this chapter, but my preference is for the addition of a well-vascularized tissue flap. This has produced the best and most predictable outcome over a wide range of patients and clinical situations.

Flap reconstruction of the postlumpectomy deformity is complicated by the paucity of local flaps. Skin rearrangements adjacent to the scar are suitable for only the smallest and most superficial defects. There is a paucity of local tissue. I have no experience with the lateral thoracic skin flap because I believe that the donor scar is prohibitive in most patients. This flap has been described for postlumpectomy deficit reconstruction, however.

The workhorses in my practice have been the transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap and the latissimus dorsi flaps as illustrated later in this chapter. These flaps can provide variable amounts of new tissue, and their use in breast reconstruction is standardized. The latissimus is excellent for defects situated laterally, superolaterally, and inferolaterally, while the TRAM is better suited for the reconstruction of inferior, central, and medial defects. To reconstruct defects in these locations with a latissimus flap, dissection through the breast is required to position the flap. Therefore its use has been limited in my hands to defects located in the outer half and occasionally the inferior pole of the breast. The TRAM flap (whether free or pedicled) is also the most useful technique when there is a need for significant volume restoration or skin replacement.

I believe that the volume of resected tissue relative to the total volume of the breast is the most important determinant in the genesis of the postlumpectomy deformity (see

Fig. 9-9). The next most critical factor is the location of the resection. Tumor resections that are carried out immediately above or immediately inferior to the NAC are responsible for the large majority of postlumpectomy deformities that require a major reconstruction, with the resections in the inferior pole of the breast resulting in the worst cosmetic outcomes (

Fig. 9-11A,

B). Other predictive factors for a poor outcome are reoperations for reestablishment of a tumor-free margin and intervening infection in the lumpectomy wound. Finally, better outcomes at the site of the excision from the standpoint of breast contour are seen in patients whose breast flaps are kept thick as opposed to those patients whose skin flaps are thin.

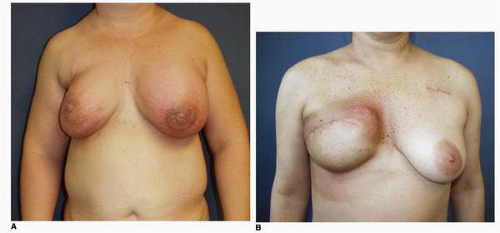

The therapeutic radiation administered to the breast(s) also plays a role in the etiology of the problems encountered by the reconstructive surgeon. It is has long been accepted that radiation therapy produces effects on all tissues subjected to it. These effects are indiscriminate (i.e., radiation therapy affects both the tumor cells and the surrounding tissues), and they are permanent, continuous, and progressive.

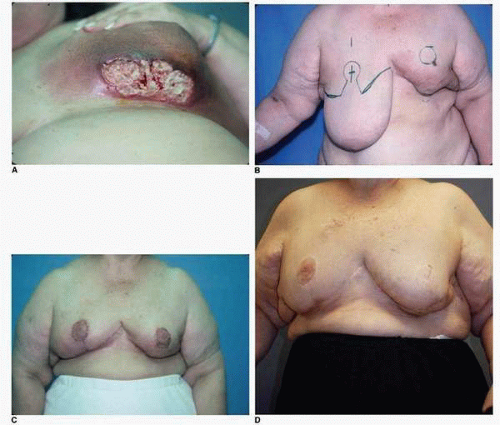

The injury produced by radiation therapy and the time line of healing are generally understood as follows. The acute phase of tissue repair following radiation therapy is noted during and up to 6 weeks following such treatment. It can be marked by redness, blisters, or frank ulceration of the skin (

Fig. 9-12A,B). After this time the skin exhibits edema and definite induration. Clearly, advances in the science of radiation therapy and refinements in the technology and instrumentation used for its administration have dramatically decreased such acute radiation injury to the skin and have almost completely eliminated persistent skin ulceration. However, such presentations are occasionally still seen (

Fig. 9-13A-D).

The subacute phase of wound healing following such treatment occurs over the ensuing 6 months and is marked by hyperpigmentation and often a tactile quality of woodiness in the breast tissues that is apparent to the patient and the surgeon.