8.1 Reduction mammaplasty

Synopsis

Macromastia, or mammary hypertrophy, is a disease process that can result in physical and psychological symptoms.

Macromastia, or mammary hypertrophy, is a disease process that can result in physical and psychological symptoms.

Macromastia symptoms rarely improve without surgical intervention, which typically results in significant improvement in the patient’s quality of life.

Macromastia symptoms rarely improve without surgical intervention, which typically results in significant improvement in the patient’s quality of life.

Reduction mammaplasty techniques have evolved over millennia, with particularly great strides made in the last 100 years.

Reduction mammaplasty techniques have evolved over millennia, with particularly great strides made in the last 100 years.

Currently, there exist several well-designed techniques based on sound surgical principles to address macromastia via reduction mammaplasty.

Currently, there exist several well-designed techniques based on sound surgical principles to address macromastia via reduction mammaplasty.

Introduction

Patients with mammary hypertrophy can present with a variety of symptoms. Typical complaints include neck and back pain, shoulder grooving from bra-straps indenting the skin, headaches, difficulty finding well-fitted clothes and limited ability to exercise. Psychosocial issues surrounding excessively large breasts also exist, creating a focal point for embarrassment for women, especially teenagers and elderly women. Often, women with mammary hypertrophy experience intertriginous skin maceration and other rashes, as well as infections – all the result of heavy, pendulous breasts.1 Netscher et al. evince that macromastia patients’ symptoms are better defined with regard to the constellation of their symptoms rather than the volume of excess breast tissue that need be removed. Further, their work shows that disease-specific group of physical and psychosocial complaints are more directly related to large breast size than to being overweight.2 Kerrigan et al. showed that the symptoms associated with macromastia represent a significant health burden, and that nonsurgical interventions such as weight loss and special bras do not allay these symptoms.3 The main purpose of breast reduction is to address these symptoms and, in doing so, improve the quality of life of the women who suffer from mammary hypertrophy. Blomqvist et al.4 investigated the health status and quality of life of patients who underwent reduction mammoplasty. They conducted a prospective questionnaire study in 49 women who were 20 years or older, using preoperative and postoperative assessments at 6 and 12 months. The questionnaire included four parts: part I assessed pain in the neck, shoulders, back, breast, bra strap indention, and head, whereas part II assessed effects of breast size and weight on body posture, sleep, choice of clothing, sexual relations, and working capacity; part III assessed preoperative expectations for the operation in comparison with postoperative result using a scale of 1–6; part IV consisted of an international health-related quality-of-life questionnaire, the SF-36, which was standardized for the Swedish women queried in the study. The authors found that reduction mammaplasty provided significant reduction of pain in all locations (p < 0.001), with an average weight of resected tissue being 1052 g. Furthermore, the improvements continued up to 12 months postoperatively. The patients’ main subjective problems related to the size and weight of the breast were body posture and choice of clothing, and the authors demonstrated significant improvements of all subjective problems (p < 0.001) except sleep. The patients’ expectations were met to a high extent, and, in some areas such as intimate situations, femininity, and social contacts, the results exceeded the preoperative expectations. Preoperatively, the mammaplasty patients scored significantly lower (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001, depending on area) in SF-36, which indicated patients had lower quality of life compared with women in the same age group. Postoperatively, patients reported a significantly improved quality of life. These results were similar at 6 and 12 months, indicating long-term improvement. After 1 year, there was no statistically significant difference between the post-reduction patients and the age-matched unoperated women, which suggested those women were normalized in health-related quality of life.4

Though the symptomatic improvement of patients suffering from mammary hypertrophy is the primary goal of reduction mammaplasty, there is another goal that is nearly as equally important – creating a more aesthetic breast. In fact, Spear describes the reduction mammaplasty as “the clearest example of the interface between reconstructive plastic surgery and aesthetic plastic surgery.”1

History

One of the earliest descriptions of breast reduction is from the writings of Paulus Aegenita, who described a detailed account of what is thought to be the first surgical correction of gynecomastia in the 7th century AD.5 Adams’ translation from Greek of Aegenita’s treatment of gynecomastia is illustrative:

Wherefore, as this deformity has the reproach of effeminacy, it is proper to operate upon it. Having, therefore, made a lunated incision below breast, and dissected away the skin, we unite the parts by sutures. If the breast incline downward, owing perhaps to its magnitude, we make in it two lunated incisions, meeting together at the extremities, so that smaller may be comprehended by the larger, dissecting away the intermediate skin, removing the fat, we use sutures in like manner.6

One of the first cases of reduction mammoplasty in a female patient was submitted by Dieffenbach in 1848,7 who reduced the lower two-thirds of the breast via an inframammary fold incision. Later in the 19th century, Pousson described a superior wedge resection technique that addressed both ptosis and excessive mammary parenchyma in cases of macromastia.8 From the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, there were many approaches to reducing breast tissue, which, more often than not, actually attempted to correct breast ptosis. Various techniques for skin and parenchymal resections were used, but none employed transposition of the nipple-areola until Morestin in 1909.9 Resections of up to 1400 g were being reported in this time frame, mostly using an inframammary approach, such as that described by Morestin and Guinard.10

The 1920s saw the advent of more reliable operations in the work of Thorek, Aubert, and Passot.11–13 Thorek published his breast amputation technique in 1922, which consisted of a lower pole amputation and free nipple graft. His technique is still used with some modifications even today for extremely large breasts.11 The next year, Aubert put forth his technique for reduction mammoplasty, which emphasized the import of minimizing dissection of the skin overlying the breast parenchyma to minimize vascular complications.12 In 1925, Passot described transposition of the nipple-areolar complex into a buttonhole incision more cephalically on the breast mound, which results in no vertical scar on the reduced breast (Fig. 8.1.1).13 The late 1920s and early 1930s continued to offer technical advances in reduction mammoplasty. Schwarzmann posited that the perfusion and viability of the nipple-areolar complex could be improved if a ring of dermal tissue was left around it, thereby allowing more successful transposition of the nipple-areola. This innovative idea is the forerunner of the various reduction mammoplasty techniques used today that base the nipple-areola on a dermoglandular pedicle (Fig. 8.1.2).14 Another vanguard event in the history of breast reduction came with Biesenberger, who was the first to develop a reproducible parenchymal pedicle-based technique with a “cut as you go” skin resection pattern (Fig. 8.1.3).15 The procedure results in an inverted-T scar and relies heavily on wide subcutaneous undermining with folding of the breast pedicle. Though it was lauded for its reproducibility, Biesenberger’s technique resulted in high rates of skin and nipple necrosis. Yet it remained one of the most popular techniques well into the mid-20th century.

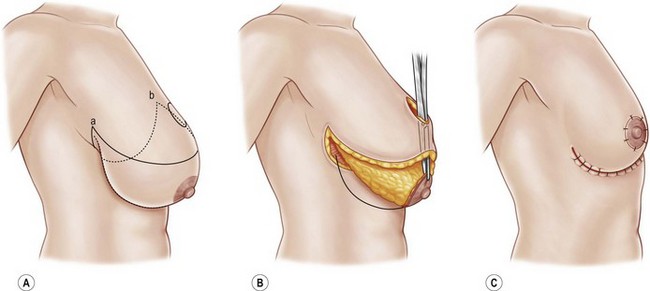

Fig. 8.1.2 (A–D) Schwarzmann reduction with superomedial dermoglandular pedicle.

(Redrawn after Lickstein LH, Shestak KC. The conceptual evolution of modern reduction mammoplasty. Operat Tech Plast Reconstr Surg 1999; 6:88–96.)

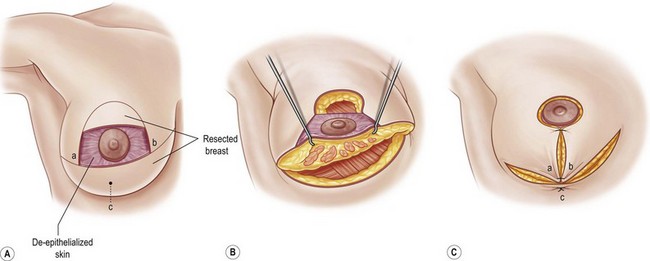

Fig. 8.1.3 (A–E) Biesenberger reduction – degloving the breast with inverted T closure.

(Redrawn after Lickstein LH, Shestak KC. The conceptual evolution of modern reduction mammoplasty. Operat Tech Plast Reconstr Surg 1999; 6:88–96.)

Advances in reduction mammoplasty continued in the 1940s and 1950s with the concept of preoperative planning being brought to the forefront by Aufricht, Bames, and Penn.16–18 In 1949, Aufricht stressed preoperative geometric planning for parenchymal resections, rather than working free-hand intraoperatively. His technique centered on a superior parenchymal resection, supplying the nipple-areola on an inferior pedicle but preserving lateral and medial pillars and their inherent perforators. Further, he emphasized the importance of redraping the skin after parenchymal resections in reduction mammoplasty.16 Bames reported his experience with a similar technique, noting the significance of preoperative markings in planning parenchymal resections.17 Aesthetic concepts of nipple areolar complex position were introduced by Penn in 1955, noting that sternal notch-to-nipple distances should be 21 cm and the nipple-to-nipple distance should be the same – to form an equilateral triangle.18 In 1956, Wise employed these concepts of preoperative marking, geometric parenchymal resections, and nipple-areolar complex placement, when he introduced his keyhole pattern of skin resection. Ultimately resulting in an anchor or inverted-T shape, the Wise pattern of breast reduction became the most reliable and reproducible breast reduction technique and remains one of the most popular techniques to this day.19

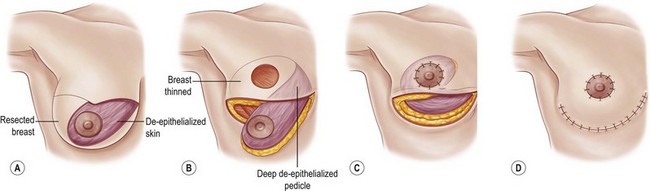

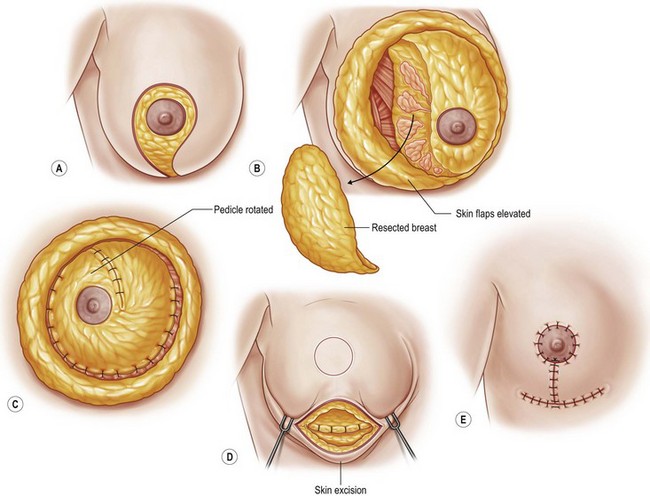

The 1960s and 1970s saw vast and different approaches toward the end of improving the pedicle in breast reductions. Strombeck demonstrated a horizontal bipedicled flap to maintain the nipple-areolar complex in 1960, thereby capitalizing on the work of Aufricht and Bames (medial and lateral perforators for perfusion, as well as innervation) and Schwarzmann (dermoglandular pedicle) (Fig. 8.1.4).20 The superolateral dermoglandular pedicle was described by Skoog in 1963, whereas Pitanguy and Weiner described superiorly-based dermoglandular pedicle some 10 years later in 1973 (Fig. 8.1.5).21–23 Orlando and Guthrie devised the technique of the superomedial dermoglandular pedicle shortly thereafter in 1975, with an eye on maintaining upper pole volume.24 In 1977, Courtiss and Goldwyn, and Georgiade, among others, made advances in inferior pedicle techniques (Fig. 8.1.6).25–28 Five years prior, McKissock modified Strombeck’s horizontal bipedicle technique into a vertical bipedicle technique. This required thinning of the superior and inferior portions of the bipedicled flap to allow folding, and resultingly does not have as much perfusion as other techniques (Fig. 8.1.7).29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree