Chapter 53 Reconstruction of the head and neck

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Introduction

Burn injuries constrict and deform the face, distorting its features, proportions and expression.1 Burns also alter the surface of the facial mask by causing scars and altering texture and pigmentation. The changes to the surface of the skin are deforming but are much less important to facial appearance than are the changes in proportion, features, and expression. The removal of scars should not be the primary goal of facial burn reconstruction. A normal looking face with scars is always better looking than an even slightly grotesque looking face with fewer scars. Mature scars that result from burn injury will often be less conspicuous than surgically created scars or surgically transferred flaps or grafts. The subtle and gradual transition between unburned skin and burn scar is an excellent example of nature’s camouflage and can render scarring remarkably inconspicuous. The principal goal of facial burn reconstruction should be the restoration of a pleasing and tension-free facial appearance with appropriate animation and expression.2 If this goal is kept in mind and pursued with persistence and determination, the amount of improvement that can result after severe facial burn injury can be remarkable. Ignoring this basic principle can result in iatrogenic catastrophes during reconstructive surgery of the head and neck following burn injury.

Successful reconstruction of burn deformities of the head and neck requires a well-functioning and extensive team.3 Major burn deformities in this area can be intimidating and overwhelming. Experience and a specialized infrastructure are required to take care of these patients comfortably and successfully. Familiarity with their unique problems and a firm commitment to correcting their challenging deformities is required from all members of the reconstructive team. The care of a patient from the onset of a major burn involving the head and neck to a successful reconstructive outcome requires skill, patience, determination, and enthusiasm from all who are involved.

Acute management

Although the main focus of this chapter is the reconstruction of established facial burn deformities, an understanding of the acute care of facial burn injuries is necessary in order for the surgeon to have an accurate perspective. Excision and grafting of deep second-degree and full-thickness burns has become the standard of care since it was first proposed in 1947.4–6 It remains controversial whether this is the optimum treatment for facial burn injuries. Early excision and grafting of the face is problematic because of the difficulty in diagnosing the depth of the facial burn and accurately predicting an individual patient’s long-term prognosis both functionally and aesthetically. The overwhelming majority of facial burns treated conservatively with a moist regimen of topical antibiotics will be healed within 3 weeks. Burns which are clearly full-thickness are best treated by early excision and grafting within 7–10 days to promote early wound closure and minimize contractile forces (Fig. 53.1). The problem cases are those where healing has not occurred by 3–4 weeks or longer. Early tangential excision and grafting has been proposed for these patients in order to achieve more favorable healing with less eventual contracture deformities.7 Proponents of conservative therapy argue that early excision and grafting may result in a patient with a grafted face who would otherwise have healed favorably by successfully epithelializing their partial-thickness burn from skin appendages.8 Conservative management has been facilitated by the myriad ancillary techniques currently available to favorably influence the healing of facial burns such as pressure, silicone, silicone-lined computer-generated facemasks, topical and interlesional steroids, vitamin E, massage, and treatment with the pulsed-dye laser. Impressive results have been obtained by advocates for early excision and grafting.9 Very good outcomes, however, can also be achieved by being more conservative with this difficult group of patients (Fig. 53.2). The majority of acute facial burns are treated conservatively in most burn centers, with early excision and grafting limited to those cases where it is clear that a full-thickness burn injury has occurred.

Pathogenesis

Superficial second-degree burns usually heal without scarring or pigmentary changes. Medium-thickness second-degree burns which epithelialize in 10–14 days usually heal without scarring, although there can be long-term changes in skin texture and pigmentation. Deep second-degree burns which epithelialize after 21 days or longer must be carefully managed for they have a propensity to develop severe late hypertrophic scarring (Fig. 53.3). These patients should be closely monitored after initial healing and at the first sign of hypertrophy must be managed with all available ancillary treatment modalities. Pressure garments have been shown over several decades to be effective in suppressing and reversing hypertrophic scarring. Adding silicone to pressure therapy seems to increase its efficacy. Computer-generated clear face masks lined with silicone have improved the ability to deliver pressure to facial hypertrophic scars and are better tolerated by patients (Fig. 53.4). When tension plays a role in the development of early hypertrophic scarring, relief of the tension with either focal z-plasty or judicious release and grafting can be very helpful. Full-thickness facial burns should usually be excised and grafted unless focal and small.

Evaluation of facial burn deformities

Facial burn reconstruction should be based on an overall strategy and a clear understanding of the fundamental problems. Many reconstructive techniques have been described in the literature and most can be successful if the strategic goals are appropriate.10–12 The best reconstructive plan is usually a judicious combination of contracture releases by z-plasty, grafts, and flaps, followed by appropriate scar revision.2

Deep second- and third-degree burns heal by contraction and epithelialization. The more severe the burn injury, the more contraction takes place during the healing process. The changes in facial appearance following a deep second-degree burn injury are dramatically demonstrated in Figure 53.5. Three weeks following a deep second-degree burn, the patient’s facial features and proportions remain essentially normal. Six months later, contractile forces have deformed the facies in a pattern that is repeated to a variable degree in virtually all severe facial burns. These changes make up the stigmata of facial burn injury and are listed in Box 53.1. The eyelids are distorted with ectropion, the nose is foreshortened with ala flaring, the upper lip is shortened and retruded with loss of philtral contour, the lower lip is everted and inferiorly displaced, the lower lip is wider than the upper lip in anterior view. The tissues of the face and neck are drawn into the same plane with loss of jawline definition. The severity of these changes is proportional to the severity of the injury.

Fortunately, the majority of facial burn injuries are not severe and do not involve the entire face. A relatively small number of patients sustain injuries which deeply involve the entire face such as shown in Figure 53.5. It can be helpful to separate patients with facial burn deformities into two fundamentally different categories as described in Box 53.2. Type I deformities consist of essentially normal faces that have focal or diffuse scarring from their burns and may have associated contractures. Type II deformities make up a much smaller number of patients who have ‘pan-facial’ burn deformities with some or even all of the facial burn stigmata. Although these categories are not rigidly defined and there are some patients who do not fit neatly into one or the other, understanding the fundamental difference between these two groups of patients can help define treatment goals. It can also aid in selecting the most appropriate methods for reconstructive surgery.

Patients with type I deformities have an essentially normal facial appearance despite scars from their burns. In these patients, one must be certain that surgical intervention does not adversely alter normal facial features or create distortion from iatrogenically induced tension. Overall facial appearance should not be sacrificed in an effort to ‘excise scars.’ The best reconstructive options for patients with type I facial burn deformities are usually scar release and revision with z-plasties, full-thickness skin grafts, or tissue rearrangement with local flaps. The pulsed-dye laser can be helpful for decreasing post-burn erythema and treating persistently erythematous burn scars. Full-thickness skin grafts are excellent for focal contractures. Z-plasties in combination with the pulsed-dye laser can be a powerful scar-improving combination (Fig. 53.6). Excision of scars and resurfacing operations in aesthetic units and major flap transpositions with or without tissue expansion are rarely indicated.

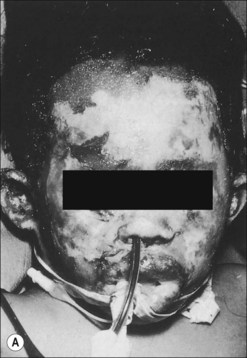

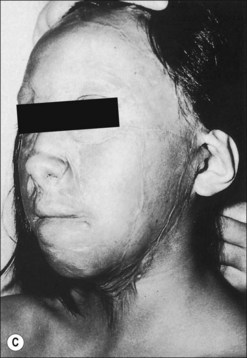

The much less frequently encountered group of patients with type II facial burn deformities presents a completely different clinical situation. Examples of patients falling into the type II category are shown in Figure 53.7. The surgical goals for this group of patients should be the restoration of normal facial proportion and as much as possible the restoration of the position and shape of normal facial features. The intrinsic and extrinsic contractures that exist in these patients require large amounts of skin. The correction of these contractures should be carried out in a carefully planned and staged fashion. The sequence of operations is usually the following: eyelids, lower lip and chin, upper lip, cheeks, nose, and then other residual deformities. As each area is reconstructed, the addition of skin results in the relief of tension, which benefits other areas of the face. Excision of normal skin or elastic healed second-degree burned skin is almost never indicated. After facial proportion has been achieved and facial features have been restored to their normal location and shape without tension, scar revision can be carried out to smooth and blend the remaining junctional scars (Fig. 53.8).

Figure 53.7 (a,b) Typical examples of patients with ‘pan-facial’ burns resulting in type II facial deformities.

Fundamental principles and techniques

Aesthetic units

The concept of facial aesthetic units has profoundly affected plastic surgical thinking since its introduction by Gonzalez-Ulloa.13 Initially conceived as the ideal approach for resurfacing the face following burn injury, this important concept has been emphasized in virtually all subsequent writings about facial burns. It is important to keep facial aesthetic units in mind during burn reconstruction but the desire to adhere to this concept should not supersede common sense. When small unburned and unimportant islands of skin are in an aesthetic unit that is being resurfaced, they can be sacrificed. Otherwise, the excision of normal facial skin is rarely indicated in burn reconstruction. All burned faces to some degree are mosaic. Scar revision with z-plasties is an excellent technique to camouflage scars in a burned face. Mosaic faces which are proportional, tension free, and normally expressive appear much better in real life than they do in images.

Z-plasty

The z-plasty operation is a powerful tool in the surgeon’s armamentarium for facial burn reconstruction. The z-plasty has been used for over 150 years to lengthen linear scars by recruiting lax adjacent lateral tissue.14 Z-plasty can also cause a profound beneficial influence on the physiology of scar tissue when it is carried out within the scarred tissues rather than after excising them.15 The physiology of this phenomenon is related to the immediate and continuing breakdown of collagen which occurs in hypertrophic scars following the relief of tension.16 Z-plasty also narrows scars at the same time that it lengthens them. In addition, the z-plasty adds to scar camouflage by making the borders of the scar more irregular. In order for z-plasties to lengthen a burn scar and restore elasticity, the lateral limbs of the z-plasty must extend beyond the margins of the scar. The improvement in the appearance of facial scars following z-plasty and without any scar excision can be dramatic, particularly when combined with pulsed-dye laser treatment (Fig. 53.6).

Laser therapy

Hypertrophic scarring is a frequent complication after partial-thickness facial burn injuries which take longer than 3 weeks to completely epithelialize.17 Despite conservative management and close monitoring, hypertrophic scarring can become severe during the first two years after the burn (Fig. 53.3).18–20 The pulsed-dye laser (PDL) has emerged as a successful treatment modality during this period of scar proliferation and is an effective alternative to scar excision in patients with hypertrophic facial burn scars.21,22 Multiple studies have demonstrated its beneficial effect on scar erythema and hypertrophy.23–27 The PDL also rapidly decreases pruritus and pain23,24 and provides an additional, low-morbidity, therapeutic intervention for patients and their families during the often prolonged period of scar maturation. Restoration of hypertrophic facial scars to their previous state of a flat, epithelialized surface is a superior outcome to surgical excision with its concomitant increase in facial tension.22 The development of fractional ablative and non-ablative laser therapy using various types of lasers including CO2 and Erbium-YAG offer promising new options for the management of facial burn scars in the future (Fig. 53.9).28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree