Chapter 50 Reconstruction of burn deformities

An overview

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

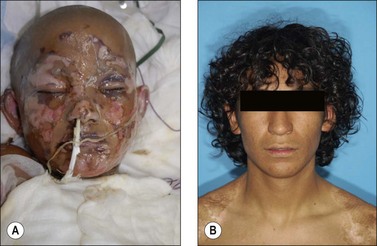

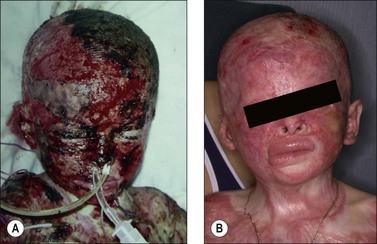

The severity of burn injuries is usually assessed, if not by patient survival, by the consequence of burn injuries, i.e. scar hyperplasia/hypertrophy, scar contracture, and structural deformities due to loss of bodily components. Since the bodily deformity is closely related to the magnitude of injuries, restorative procedures are seldom indicated if the depth of injury is superficial and the burned area limited (Fig 50.1) but are required for deep burns (Fig 50.2).

The possibility of surviving burn injuries has changed dramatically over the past 30 years, attributable singularly to an aggressive approach in surgical treatment of burn wounds, i.e. early wound debridement and wound coverage.1–3 It is ironic that the success attained in burn treatment has resulted in a higher number of patients who will need to undergo reconstruction because of an aggressive ‘life-saving’ surgical treatment.

Formation of scar tissues at a wound site and contraction of the scar tissues are the normal consequence of an injury. Although the exact mechanisms accounting for the sequential changes in wound healing and scar formation remain incompletely understood, wounds with infection and/or those allowed to heal spontaneously, for instance, tend to result in a thickened scar that is contracted circumferentially; an observation suggestive that various fibrogenic cytokines such as transforming growth factor β could play an important role in the pathogenesis of otherwise clinically undesirable consequences.4,5

Thickened and contracted scar tissues, i.e. the changes that are ‘normal’ and ‘expected’ consequence of the wound healing processes, are microscopically composed of collagens arranged in whorls and nodules. The changes may be observed as early as 3–4 weeks following the injury and they are cosmetically unsightly and functionally disturbing (Fig. 50.3).

Reconstruction of burn deformities

General principles

Burn injuries are a traumatic illness resulting in aberrant body physiologic processes caused by thermal destruction of the skin. The altered physiologic processes will affect not only the healing of the original burn wounds but also healing processes of the secondary surgical procedures aiming to restore the consequence of the original injuries. The treatment, under an aberrant physiologic circumstance, should aim to repair the burn wounds first. Attempts to restore deformities should be delayed until recovery from the initial phase of injury is complete.6

Early treatment of deformity

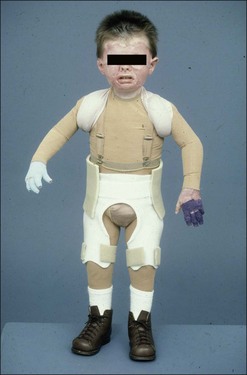

Of the consequences of burn injuries, hyperplasia and contracture of resultant scars at wound sites and the contraction of mobile bodily parts, i.e. eyelids, neck, axilla, elbow, hands-fingers, groin, knee and ankle-foot, are two most common problems that are in need of attention. The regimen of applying pressure upon scar tissues and of immobilizing joint structures has been advocated to minimize the undesirable consequences of scarring and scar contracture (Fig. 50.4).

Although the true efficacy of a non-surgical regimen to control the deformities has not been established, the frequency of secondary joint release among individuals who ‘endured’ the morbidities associated with proper joint splinting for a period of no less than 6 months has been noted.7,8 The use of pressure dressing, especially in the areas such as upper and lower limbs, with proper splinting of the hand and fingers is strongly recommended soon following the injury. The regimen of non-surgical management of burn deformity must include daily physiotherapy and exercise to maintain joint mobility and to prevent muscle wasting.

Assessment of burn deformities

Indication and timing of surgical intervention

The 2-year ‘moratorium’ on early burn reconstruction, in some ways, is justifiable. Operating on an ‘immature’ scar characterized by redness and induration is technically more cumbersome; hemostatic control of the wound is difficult and inelasticity and lack of tensile strength noted in scar tissues render tissue manipulation more difficult. A high rate of contracture noted in instances where a partial-thickness skin graft is used for releasing a wound showing active inflammatory processes may further support the advocacy of two years of delay in initiating burn reconstruction.9

Our recent change in handling individuals who were in need of reconstruction followed the finding that contracted bodily parts can be effectively reconstructed in the first 2 years post-burn if skin flap, fasciocutaneous flap or musculocutaneous flap techniques are used. Reconstruction is initiated in individuals as early as 3–6 months following the initial injury. The approach is well-suited for those encountering functional difficulties because of scarring and scar contracture.10

The techniques of reconstruction

Primary wound closure technique

The margins of scar requiring excision are marked. It is important to determine the amount of scar tissue that can be removed, yet the resultant defect could be closed directly. ‘Pinching’ the edge of scar at three or four different sites along the length of scar to determine the mobility of the wound edges is the simplest yet most reliable method to determine the amount of scar tissues that can be removed safely. Leaving a rim of scar tissue is generally necessary unless the size of scar is so small that removal and direct closure of the resultant wound would not lead to contour deformity. A circumferential incision is made in the line marked and is carried through the full thickness of the scar down to the subcutaneous fatty layer. While the outer layer of the scarred tissue is excised, 4–5 mm of collagen layer is left attaching to the base. The conventional approach of wedged scar excision will result in depression along the site of scar excision, an iatrogenic consequence that could be difficult to amend secondarily. In order to minimize vascular supply interference along the wound edges, undermining of scar edge should be kept minimal. Synthetic sutures are preferred for wound closure (Fig. 50.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree