Fig. 10.1

Macular lesions

Fig. 10.2

Plaque lesions

Fig. 10.3

Nodular lesion

Fig. 10.4

Tumoral lesions

10.2.2 Endemic (African) KS

It accounts for up to 9 % of all malignancies in central Africa, with a male to female ratio of 18:1 (adults). The mean age of onset is of 36 years in females and 40 years in males. Clinically the disease is often similar to classic KS. The form that arises in middle-aged adults commonly follows an indolent course favouring the lower limbs. In children it is described a lymphadenopathic form rapidly progressive and generally fatal, with a male to female ratio of 3:1.

10.2.3 Transplant-Related (Iatrogenic) KS

It is a rare form of KS, presenting as an indolent or, rarely, aggressive disease in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, with organ transplants, cancer or autoimmune diseases.

Clinically the lesions are similar to those observed in classic KS. Both systemic and cutaneous involvement may occur. It may resolve completely upon ending of immunosuppressive therapy.

The progression of the disease may be aggressive, causing the death of the patient.

10.2.4 HIV-Related (Epidemic) KS

The outburst of the disease began in the late 1970s and in the pre-HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral Treatment) era, about 40 % of AIDS-affected homosexual men developed KS, compared with less than 5 % in other risk groups.

It has declined substantially after the introduction of HAART (1997) and for the avoidance of high-risk sexual practices.

Clinically, it is characterized by either small round or oval pink to reddish macules.

Initial lesions frequently develop on the face and on the trunk. In prolonged courses, KS lesions may be disseminated, often coalescing to form large plaques. The oral mucosa, primarily the palate, is the initial site of localization in 10–15 % of all HIV-KS patients (Fig. 10.5a–c). The involvement of viscera, including the gastrointestinal tract, lymph nodes and lungs is frequent.

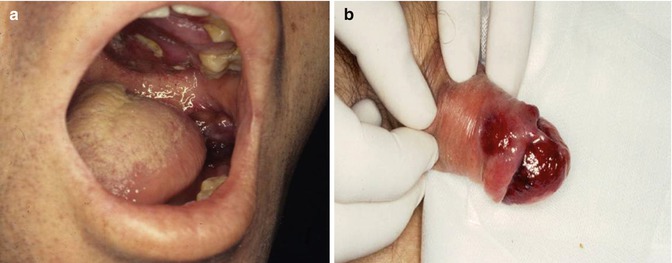

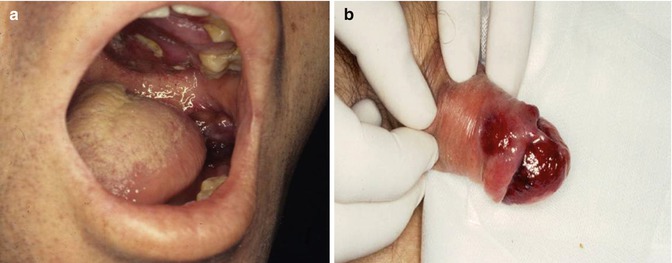

Fig. 10.5

(a–c) Typical presentations of HIV-related KS lesions

10.3 Histopathology

To the different clinical expressions of the disease correspond the distinct histopathologic pictures [3].

In the patch stage a dermal proliferation of small, thin-walled, irregular lymphatic-like channels is prevalent around pre-existing normal blood vessels and adnexal structure.

In the plaque stage there is an exaggeration of the patch stage features with involvement of the whole reticular dermis and even the subcutis.

The nodular stage is characterized by well-defined mostly dermal tumours composed of intersecting fascicles of uniform spindle cells which show only mild cytological atypia and frequent mitotic figures. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies have firmly established the endothelial nature of KS.

10.4 Aetiology

In recent years the role of HHV-8 tumorigenesis of all forms of KS has been hypothesized, after the detection of viral DNA sequences in many cases. This virus was first identified in KS cells of a patient with AIDS and now is known to be present in most patients with all clinical types of KS [6].

10.5 Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes many clinical pictures also according to the stage of the disease.

In macular stage one would consider angiosarcoma, benign lymphangiomatosis, microvenular haemangioma and hobnail haemangioma; in nodular stage Kaposiform haemangioendothelioma and spindle cell haemangioma; and in late stage acroangiodermatitis of chronic venous insufficiency and Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma) [2].

10.6 Staging

To assess the stage of the disease, the more common investigations performed are the following: involved tissues biopsy with histopathological examination, haematological and biochemical studies, chest radiography and, when clinically indicated, gastrointestinal radiography or endoscopy, abdominal ultrasound or computerized tomography scan [7].

10.7 Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy, as all therapies for KS, must be individualized and its planning depends upon size, location and number of lesions, presence or absence of symptoms, overall state of health including comorbidities and goals of therapy (palliation vs. cure).

KS is a tumour relatively radioresponsive. Radiotherapy can be used for different scopes: curative, as far as possible in spite of the multicentric features for classic KS, and palliative or reducing the extent of the disease in HIV-related KS. It is a treatment option for the patients presenting with multifocal but relatively localized KS. Furthermore, typical indications for radiotherapy are palliation of pain, bleeding or lymphoedema and improvement of cosmetic appearance. It is the treatment of choice for the majority of patients with nodular disease of the extremities.

After the introduction of HAART (1997), the employ of radiotherapy in the HIV-related KS has become sporadic.

Local irradiation of KS includes the lesion plus a marginal tissue border in healthy skin of approximately 1–2 cm, whereas a larger margin is necessary for lesions whose edges are poorly defined. The thickness of the lesion dictates the type of radiation required. Thin cutaneous lesions can be effectively treated either by superficial X-ray therapy (50–150 kV) or relatively low-energy electron beams (4–6 MeV) and bolus. Six MeV beam penetrates approximately 2 cm into tissue with 90 % of its intensity before becoming markedly attenuated. The bolus ensures that the most superficial aspect of the tumour receives the prescribed dose and, because the bolus material absorbs some of the beam, simultaneously limits the degree of penetration of the beam into underlying tissues. Palliation of swollen and painful extremities can be achieved by covering the limb with bolus or by placing it in a water bath and applying irradiation by parallel-opposed photon portals.

High dose rate brachytherapy techniques have also been published: they are useful for lesions with a diameter not bigger than 2.5 cm; the median dose administered is 24 gray (Gy) in 3 fractions. Complete response of all lesions with no relapse is reported [8].

The literature supports the use of a wide range of doses and fractionation patterns. As long as a sufficient dose is delivered, e.g. 20–30 Gy in 10 fractions or, for small lesions, 6–8 Gy in 1 fraction [9] or 8 Gy in single dose to 30–40 Gy in 10–20 daily fractions [10], a salutary outcome is likely [11]. A conventional fractionation regimen was compared with a hypofractionated regimen in the treatment of epidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma (24 Gy in 12 fractions/20 Gy in 5 fractions). The two treatment regimens produced equivalent results for treatment response, local recurrence-free survival and toxicity [12]. As far as regards the optimal “biologic dose” of ionizing radiation to be administered, we share with other authors the opinion that the dose is around 30 Gy in 10 fractions over 2 weeks. Such value appears to provide an optimal balance between tumour control and rapidity of treatment [13].

Usually, the same dose schedules are used for all the forms of KS (equally radioresponsive).

The outcome of irradiation shows that more than 90 % of lesions respond to radiotherapy and approximately 70 % respond completely [14–18].

Some residual purple pigmentation remains in about 55 % of treated patients, especially in HIV-related KS [19].

Side effects are rare, and radiation is usually well tolerated, with minimal skin reactions, except for mucositis reaction occurring as a rule in patients with HIV-related KS and mucosal (oropharyngeal) lesions, after transcutaneous radiotherapy [20, 21]. The employ of intracavitary contact X-ray radiotherapy (ICX RT) can avoid or reduce the mucositis reactions as it has been demonstrated by a study of ours [22]. The same results may be obtained with brachytherapy to the hard and soft gum palate, using individual dental plates [23].

Yet it has been frequently observed that patients treated with extended field irradiation suffer from severe skin reactions (exudative epidermitis with skin ulcerations) in 5 % of cases [16]. Such toxicity of radiotherapy, more evident in patients affected by HIV-related KS, obviously caused by the condition of immune depression, is related to the need of treating extensive lesions or to the intention of obtaining a preventive action on disease dissemination [24].

On the skin of the pretibial area, the appearance of radiodermatitis (chronic and acute) is more frequent (due to thinning of the skin, vascular alterations and trauma possibilities). Therefore, particular attention has to be paid in the irradiation of KS lesions localized on that area, by limiting the total dose and performing small-sized irradiation fields (Fig. 10.6).

Fig. 10.6

Extensive chronic radiodermatitis of the pretibial area on nodular classic KS, irradiated elsewhere

10.8 Clinical Results

Our experience is relative to a retrospective study of 711 lesions of classic KS and 771 lesions of HIV-related KS treated with radiotherapy in the period from 1976 to 2003 [25].

10.8.1 Radiotherapy Techniques

Traditional radiotherapy techniques were used (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1

Techniques of radiotherapy

Voltage | Amperage | FSD | Field diameter | HVD | Filtration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contact X-ray therapy (CXRT) | 55–60 kV | 4 mA | 1.5–5 cm | 2–4.4 cm | 2–12 mm | – |

Half-deep X-ray therapy (HDXRT) | 100–120 kV | 6 mA |