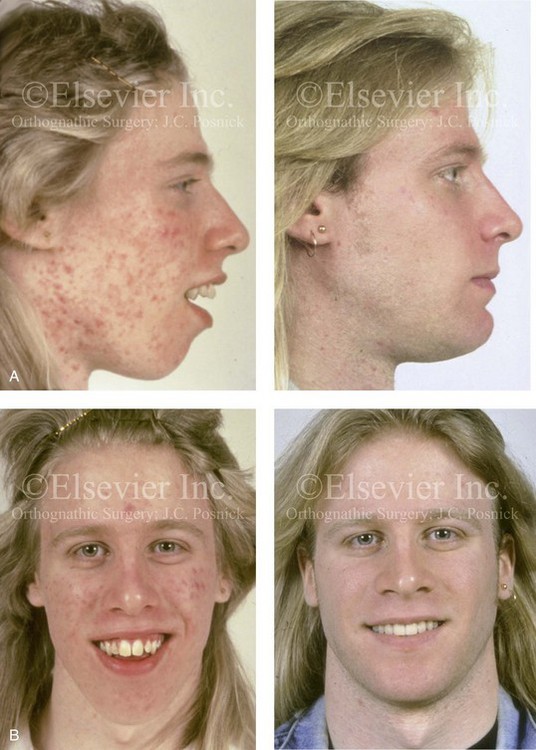

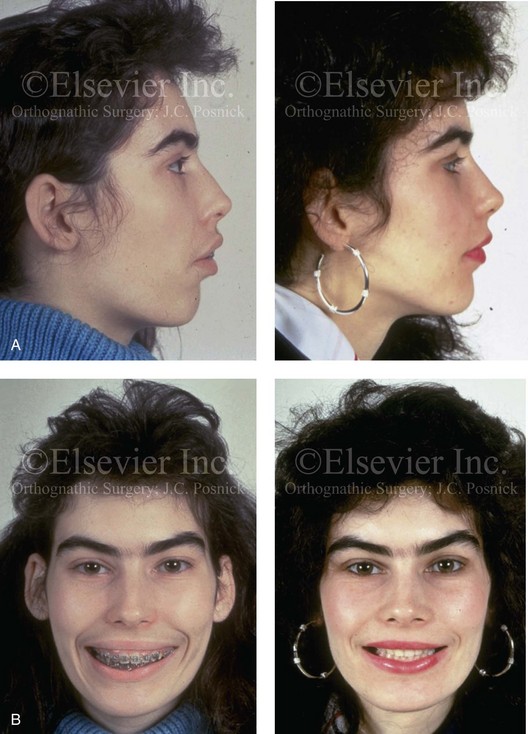

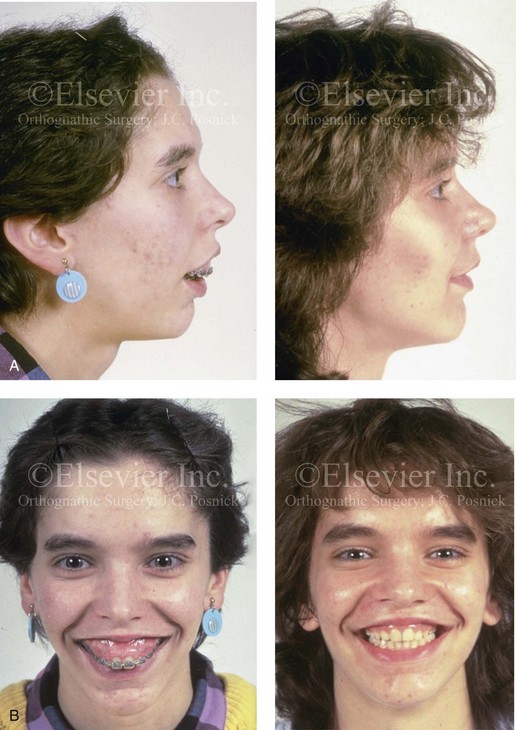

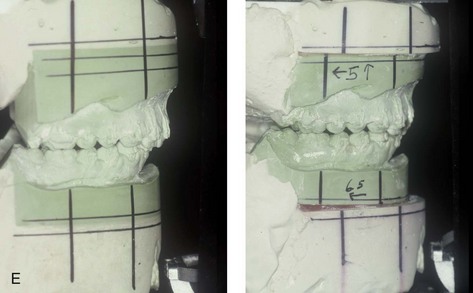

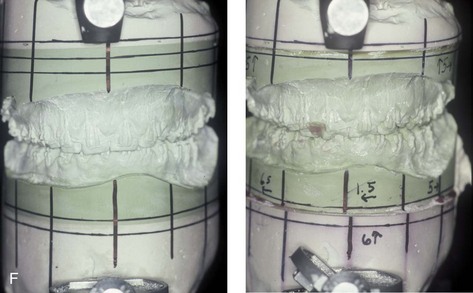

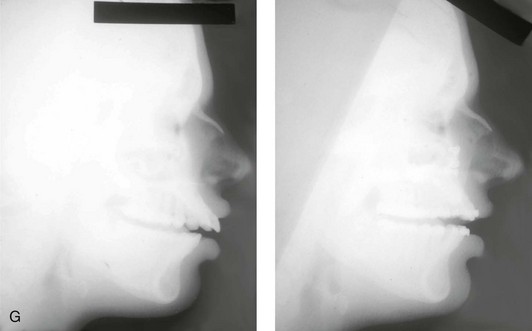

7 • Psychosocial Aspects to Consider Before Surgery • Psychological Functioning in the Individual With a Facial Deformity • Patient and Family Decision for or Against the Correction of a Dentofacial Deformity • Patient and Family Education Regarding Convalescence After Orthognathic Surgery • Patient-Centered Assessment of Surgical and Orthodontic Outcomes • Controversies Surrounding “Successful” Orthognathic Outcomes The initial discussion regarding the need for orthognathic surgery may come as a surprise to the patient and his or her family. This is especially true for the individual whose jaw dysmorphology occurred gradually during facial development, without special attention being drawn to it all of a sudden as would occur from a traumatic event, a birth defect, or after tumor resection.9,10,37,68,71,80,81,101,103 Although they have typically been aware of the malocclusion and the associated facial characteristics for at least several years, the patient and his or her family generally assume that orthodontics alone or some other minimally invasive approach is all that will be required for treatment.87 The orthodontist may have already exhausted the patient and his or her family’s energy and resources with several years of treatment to “avoid surgery” before finally “giving up.” The family may have inaccurate preconceived ideas about the surgery and the patient’s expected convalescence. The decision-making role of the parents and the compliance (i.e., the attitude) of the adolescent patient will also be important. Any dysfunctional family interactions involving the mother, the father, the patient, or the patient’s siblings, stepparents, or grandparents at this moment of stress (i.e., when a decision is needed) may also come into play. From the adolescent’s point of view, social interactions with his or her peers and concerns about the interpretation (by others) of any change in his or her appearance—as well as his or her evolving self-image and identity—will also have an impact on the situation in ways that are ongoing and somewhat unpredictable. Research confirms a correlation between an adolescent’s self-reporting of improved appearance ratings and a decrease in social, physical, and psychological problems after successful reconstruction.58,67,73,78 Patel and Kapp-Simon prospectively studied 70 teenagers who were slated to undergo orthognathic surgery.69 Before surgery, 78% stated that a functional reason was their primary motivation for undergoing orthognathic surgery. Not surprisingly, before surgery, the adolescents rated their appearance significantly less favorable than their parents did. Two years after surgery, the adolescents reported significantly increased self-confidence, and a majority (58%) felt that they had achieved improvements in their facial appearance as a result of surgery. They stated that improvements in their facial appearance would be a motivating factor for them to undergo similar surgery again. It would appear that, when all is said and done, adolescents—like adults—rate the enhancement of their facial appearance as a high priority when measuring the success or failure of their orthognathic procedures. Experience confirms it is better to openly discuss facial aesthetic aspects before surgery. This encourages the clinician to set realistic objectives, and it forces the patient and the family to confront their outcome expectations in advance. Both adolescents and adults undergoing orthognathic surgery should be screened to assess emotional baseline functioning as well as psychological readiness for surgery. The pre-surgical mental health screening should clarify any past or current symptoms of depression, anxiety disorders, panic attacks, aggression, drug/alcohol use, eating disorders, school-related problems, family or social (peer) dysfunctional relationships.4 The individual’s personal motivation to seek the correction of a dentofacial deformity is an important factor for clinicians to consider (Figs. 7-1 through 7-5).* In 2000, Rivera and colleagues surveyed 142 patients regarding their reasons for choosing to undergo orthognathic surgery.86 Seventy-one percent indicated facial aesthetic concerns, 47% stated functional issues, and 28% confirmed temporomandibular disorders as their reasons for seeking treatment. In 2007, Narayanan and colleagues surveyed 50 patients who sought orthognathic surgery and found that, for the majority, facial aesthetics rather than the correction of their occlusions was the primary motivating factor.59 In 2007, Stirling and colleagues conducted a questionnaire and interview survey of individuals who had undergone orthognathic surgery. The 46 interviewed patients stated that their primary motivations generally included both “improvement of the occlusion and to gain a more normal facial appearance.”97 More recently, Proothi, Drew, and Sachs completed a retrospective survey of 501 individuals who underwent orthognathic surgery to determine why they sought the procedures.83 The survey group was 43% male and 57% female, and the individuals ranged in age from 12 to 45 years. Seventy-six percent stated that facial appearance was negatively affected by their pretreatment jaw condition, but only 15% claimed that their appearance was their primary motivation for undergoing surgical evaluation. Thirty-six percent stated that their occlusion was the primary motivating force. Interestingly, 33% admitted to having significant speech difficulties, and 15% complained of swallowing problems that resulted from their presenting jaw deformity. Figure 7-1 A 17-year-old boy who was born with a nonprogressive congenital myopathy was referred by an orthodontist for surgical evaluation. The lack of masticatory muscle strength resulted in a constant open mouth posture. The long face growth pattern is characterized by vertical maxillary excess; a clockwise-rotated retrusive mandible; a vertically long and retrusive chin; and an Angle Class II anterior open-bite malocclusion. The patient underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach. Four bicuspid extractions relieved dental crowding. This was followed by surgery that included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical intrusion and horizontal advancement); bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); and osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement). A, Profile views before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. Figure 7-2 A 15-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She had a long face growth pattern and a Class II anterior open-bite malocclusion. She had been treated for several years with orthodontics alone, and this included four bicuspid extractions. The anterior open bite was essentially closed, with only minor degrees of malocclusion. The history and physical examination confirmed lifelong nasal obstruction, heavy snoring, and the suggestion of sleep apnea. Facial aesthetic concerns of the patient and her family included an awareness of a gummy smile, severe lip strain, a weak profile, and an irregular shape and position of the lips. The family agreed to an orthognathic approach. The procedures performed included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement with counterclockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement and vertical shortening); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. Figure 7-3 A 16-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She had a long face growth pattern in combination with asymmetrical mandibular deficiency. This resulted in difficulty with speech articulation, swallowing, chewing, and lip closure/posture. Facial aesthetic awareness of a gummy smile, lip incompetence, a weak profile, and lip irregularities was discussed. With orthodontic decompensation complete, orthognathic surgery was carried out. The procedures performed included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments, with first bicuspid extractions (vertical retrusion, arch form correction, and counterclockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, and asymmetry correction); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor contouring. A, Profile views before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. Figure 7-4 A 14-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation of a dentofacial deformity. She had a long face growth pattern that presented with excessive vertical height and significant horizontal projection and narrowness of the maxilla and the midface. She had limited airflow to the nose, severe lip incompetence, and the impression of a weak chin. Several years of orthodontics have already been carried out, and she agreed to surgical reconstruction. The procedures performed included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with first bicuspid extractions (vertical intrusion, horizontal setback, and arch correction) as well as septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal recontouring. A, Profile views before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. Figure 7-5 A 16-year-old congenitally blind girl presented with maxillary and mandibular protrusion and anterior open-bite malocclusion. Although she was unable to visualize the deformity, she felt self-conscious after years of teasing as a result of her facial appearance and her difficulties with chewing, swallowing, and speech articulation. The patient underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach. The procedures performed included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical intrusion and horizontal setback) and bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (horizontal setback). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction. E and F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment. Individuals who do not have sufficient preoperative psychological or emotional stability are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, or panic attacks and to demonstrate difficulty complying with treatment demands during the early postoperative phase.16,17,21,27 They will also have greater difficulty with an outcome that does not meet their preconceived and often incompletely articulated expectations. If so, after surgery, they may become easily frustrated and then angry, and this may involve a loss of confidence in the surgeon. They may break off communication and seek additional opinions to justify their concerns. Some may even resort to litigation should a perceived complication or suboptimal outcome occur. Recognizing and addressing these patient-specific tendencies before surgery is the best way to limit or mitigate problems after surgery. After an initial screening examination, a more in-depth psychological evaluation may be beneficial.8,18,24,96 The patient and his or her family’s motivation and the patient’s readiness for surgery should also be assessed. Unless a sufficient support system is in place, the stress of the necessary convalescence is likely to worsen any premorbid conditions in the patient. An initial screening that results in red flags for potential emotional problems is best followed up with a more focused psychological evaluation. The patient’s therapist should give clearance that the individual is considered emotionally stable enough to undergo the proposed treatment. When the treating clinicians (i.e., the surgeon, the orthodontist, and the general physician) have knowledge of the patient’s premorbid tendencies, coping strategies can be instituted proactively to minimize postoperative stress. The treating mental health professional should be available to the patient, the family, and the surgical team during hospitalization, after discharge, and throughout the patient’s convalescence. Clinical studies indicate that between 0.5% and 1.0% of late adolescent and young adult women meet the criteria for anorexia nervosa, and between 1% and 3% meet the criteria for bulimia nervosa.92 Eating disorders are multi-determined problems, and they are most commonly recognized among female adolescents. Risk factors may include a perfectionist personality type, a family history of an eating disorder, a history of trauma, a tendency toward feelings of inadequacy, and low self-esteem despite external accomplishments. Patients with eating disorders often exhibit rigid cognitive patterns that are characterized by an all-or-nothing way of thinking. Orthognathic procedures will significantly alter the diet (i.e., liquids only) and appetite level, with an expected change in nutritional intake for at least 5 weeks. Significant weight loss during the initial 2 weeks of recovery is to be expected, even among healthy individuals. The question is raised as to whether or not these dietary and postsurgical metabolic changes will tend to exacerbate a baseline eating disorder. Maine and Goldberg completed a study to determine if an elective dental manipulation—which, by necessity, results in eating discomfort and dietary restrictions—would likely influence the recovery of or result in a relapse for an individual with a baseline eating disorder.54 Three questions concerning dental and maxillofacial procedures were added to a standard questionnaire assessment of a consecutive series of 97 individuals who were entering an eating disorder therapy program. The additional questions were designed to determine the influence of dental and maxillofacial interventions on individuals with baseline eating disorders. All 97 study subjects complied with the questionnaire; 75 of the study patients were 25 years old or younger, and 53 were diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. Ongoing family or social peer conflicts or greater-than-average worries expressed by the individual or his or her family regarding the surgery, the preparation for the surgery, or the anticipated recovery period are red flags.1,29,33,41 When considering the timing of surgery for the adolescent or young adult, the family should take into account the anticipated impact on the patient’s everyday school and social activities, including examination schedules, college applications and interviews, and participation in sports activities. The surgeon’s ability to provide a clear picture of the expected recovery time and the patient’s ability to return to partial and regular activities is important and will vary according to the patient’s age and stage in life (e.g., adolescent, college or graduate student, middle-aged adult with family and work commitments). Clarifying anticipated postoperative limitations in physical, cognitive, and emotional activities is important to setting the stage for a successful outcome. It is estimated that more than 5% of individuals who are seeking cosmetic surgery consults have body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).14,19,65,91 BDD is a somatoform disorder that involves a preoccupation with a slight or imagined defect in some aspect of the individual’s physical appearance that leads to a significant disruption of daily functions. It is important to distinguish an individual with a legitimate cosmetic or functional concern from one who is hyperconcerned about minor imperfections of some aspect of his or her face. Cunningham and colleagues documented that a percentage of individuals who request orthognathic surgery will have underlying BDD.19

Psychosocial Considerations in the Evaluation and Treatment of Dentofacial Deformities

Psychosocial Aspects to Consider Before Surgery

Personal Motivation

Baseline Mental Health

Baseline Eating Disorders

Social Interaction Issues

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine