Condition

Gene

Inheritance

Familial congenital primary lymphedema (Milroy)

Lymphedema–distichiasis

Lymphedema–hypotrichosis–telangiectasia

Hennekam syndrome

Noonan syndrome

Turner syndrome

VEGFR3

FOXC2

SOX18

CCBE1

PTPN11/SOS1

XO

Dominant/recessive

Dominant

Dominant/recessive

Dominant/recessive

Dominant

Sex-linked

Morphology of Lymphatics

Primary lymphedema is a type of lymphatic malformation. Malformed lymphatic vessels in an extremity or genitalia cause accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space. Kinmonth used lymphangiography to describe the lymphatic morphology of primary lymphedema as hypoplasia/aplasia (89 %) or hyperplasia (11 %) [9]. The maldeveloped lymphatics do not have the capacity to return interstitial fluid to the venous circulation, which causes lymphedema.

Progression of Lymphedema

Fifty-eight percent of patients with primary lymphedema exhibit progression of their disease (i.e., increased volume or symptoms) [3]. Patients with unilateral lower extremity lymphedema have a 9–25 % risk of ultimately developing the condition in their contralateral extremity [3, 9]. Lymphedema progresses through 4 stages (Table 7.2) [10]. Stage 0 indicates a normal extremity clinically, but with abnormal lymph transport (i.e., illustrated by lymphoscintigraphy). Stage 1 is early edema which improves with limb elevation. Stage 2 represents pitting edema not resolved with elevation. Stage 3 describes fibroadipose deposition and skin changes [10].

Table 7.2

Clinical progression of lymphedema

Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

0 | No edema clinically, but abnormal lymphatic function |

1 | Early edema that reverses with limb elevation |

2 | Pitting edema, not reversible with limb elevation |

3 | Fibroadipose deposition, skin changes |

In the latent phase (Stage 0) the patient is unaware of his/her lymphatic dysfunction. Compensatory mechanisms, such as increased macrophage activity and spontaneous lymphatico-venous shunts, prevent swelling until lymphatic transport has been significantly reduced. Over time, pitting edema becomes non-pitting because the high-protein fluid in the interstitial space causes inflammation, fibrosis, and progressive adipose deposition [4, 5, 10]. The extremity continues to enlarge primarily because of adipogenesis. This cycle further damages functioning lymphatics. Fat in an extremity can increase by 73 % [5].

Clinical Features

Onset

Primary lymphedema can present during: (1) infancy, (2) childhood, (3) adolescence, or (4) adulthood. Although patients with primary lymphedema have malformed lymphatics at birth, individuals often develop swelling after infancy. Similar to adults with secondary lymphedema following lymph node removal and/or radiation, an interval exists between the onset of malfunctioning lymphatics and swelling. Fluid leaking out of the venous circulation is unable to be returned by the lymphatic vasculature. The high-protein interstitial fluid causes inflammation and further injures functioning lymphatics until edema is noticed clinically. Other factors, such as hormones, may influence the onset of lymphedema. For example, females most commonly present with the disease in adolescence.

Primary lymphedema traditionally has been divided according to the age of the patient when the swelling develops: “congenital,” “praecox,” or “tarda” [1]. This classification system is neither standardized nor precise, and the terms have been applied inconsistently (Table 7.3) [3, 11]. For example, “congenital” lymphedema is used if swelling was noted at birth, “shortly after birth,” birth to 3 months, birth to 1 year, or birth to 2 years. Thus, some authors would consider a 6-month-old infant presenting with lymphedema to be “congenital,” whereas others would label it “praecox.” A “congenital” anomaly may not present at birth (a child or adolescent who develops primary lymphedema was born with malformed lymphatics). “Praecox” is synonymous with “early” and relative to another time point; it does not identify an age range. A 1-day-old child with “congenital” lymphedema is “praecox” to a 1 month-old infant with lymphedema (although both would be labeled “congenital”). Similarly, “tarda” is used to describe “late” onset lymphedema, but a 1-month-old child is “tarda” to a 1-day-old neonate with congenital swelling. Developmental terminology should be used to define the onset of primary lymphedema: infancy, childhood, adolescence, or adulthood [3, 11]. These periods are defined and their use will facilitate communication and research.

Table 7.3

Onset of primary lymphedema

Historical classification | Current developmental classification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Age of onset | Definition | Age of onset | Definition |

Congenital | At birth Birth-3 months Birth-1 year Birth-2 years | Infancy | Birth-1 Year |

Praecox | Birth-35 years After birth-24 years After birth-35 years 4 Months-20 years 1–35 Years | Childhood | 1–9 Years |

Adolescence | 10–21 Years | ||

Tarda | After 20 years After 35 years | Adulthood | >21 Years |

In the pediatric population onset occurs in infancy (49.2 %), childhood (9.5 %), or adolescence (41.3 %) (Fig. 7.1) [3]. Primary lymphedema develops during adulthood in 19 % of patients (Fig. 7.2) [9]. Males are more likely to present in infancy (68 %), while females most commonly develop the disease during adolescence (55 %) [3]. The lower extremities are affected in 91.7 % of patients; 50 % have unilateral lymphedema and 50 % have bilateral disease [3]. Eighteen percent have genital lymphedema, which is usually associated with lower extremity lymphedema. Four percent of patients with primary lymphedema have isolated genital involvement. Sixteen percent of children with idiopathic lymphedema have upper extremity disease [3]. Rarely, a child can have lymphedema affecting the legs, genitalia, and/or arms (Fig. 7.3). Bilateral lower extremity lymphedema is more common in patients presenting in infancy (63 %), compared to adolescence (30 %) [3].

Fig. 7.1

Age-of-onset of primary pediatric lymphedema. With permission from Schook CC, Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Grant F, Zurakowski D, Greene AK. Primary lymphedema: clinical features and management in 138 pediatric patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 127: 2419–2431 © Wolters Kluwer in 2011 [3]

Fig. 7.2

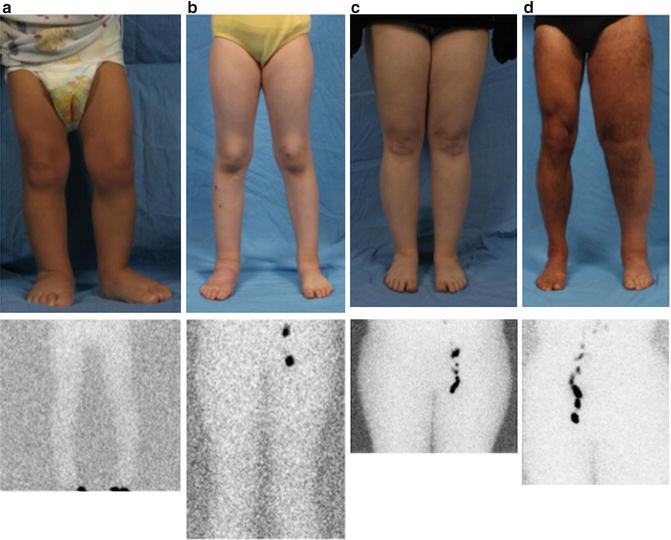

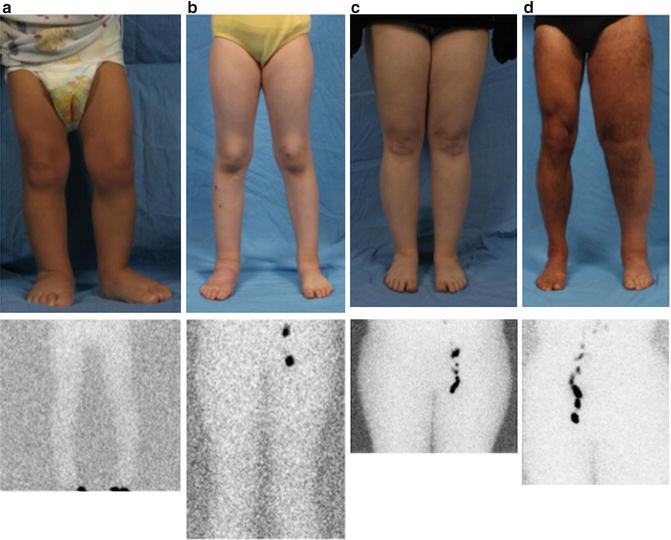

Onset of primary lymphedema. (a) Presentation in infancy: 1-year-old female with bilateral lower extremity edema since birth. Lymphoscintigram demonstrates absence of lymph node tracer accumulation in the inguinal nodes 1.5 h following injection (normal transit time is 45 min). (b) Onset in childhood: 6-year-old female with 1-year history of progressive right lower extremity swelling. No proximal transit of tracer is noted by lymphoscintigraphy 1 h after injection. (c) Presentation in adolescence: 15-year-old female with a 1-year history of right lower extremity swelling. Lymphoscintigram shows absence of tracer accumulation in the right inguinal lymph node 2 h following injection. (d) Adult onset: 48-year-old male with a 3-year history of left lower extremity swelling. Lymphoscintigram illustrates no tracer in left inguinal nodes 4 h following injection

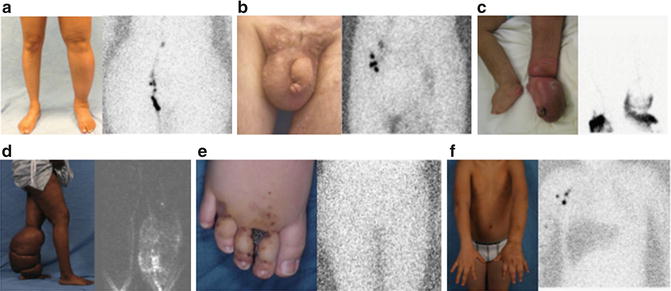

Fig. 7.3

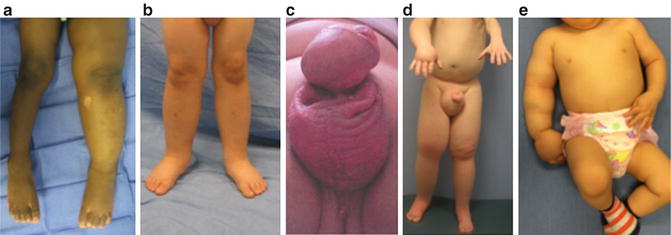

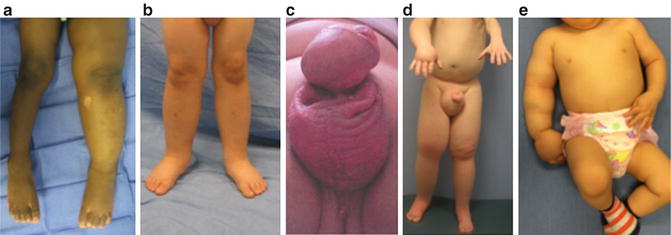

Phenotypes of primary lymphedema. (a) Infant with unilateral lower extremity lymphedema. (b) Child with bilateral lower extremity disease. (c) 14-year-old male with isolated genital lymphedema. (d) Adolescent male with right upper extremity, bilateral lower extremity, and genital lymphedema. (e) 1-year-old male with right upper extremity lymphedema

Syndromic Associations

Eleven percent of patients with primary lymphedema have a familial/syndromic association (e.g., Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome, Milroy disease) (Fig. 7.4) [3]. Children with onset in infancy and a familial history are referred to as having Milroy disease. This eponym often is erroneously applied to patients with any type of primary lymphedema. The term Milroy disease should be restricted to an infant with lower extremity lymphedema (unilateral/bilateral) present at birth with either: (1) a family history of the condition or (2) no family history of lymphedema, but a documented mutation in vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 (VEGFR3) [12]. Patients also should not be labeled as “Milroy disease” if they have either: (1) lymphedema appearing after infancy; (2) lymphedema/lymphatic anomalies outside of the extremities; or (3) associated anomalies (e.g., dysmorphic face, epicanthal folds, cardiac anomalies, or biliary atresia) [12]. A mutation in VEGFR3 is present in 75 % of children with familial lower extremity lymphedema, compared to 68 % of children without a family history of lymphedema [12]. Therefore, a positive family history of autosomal transmission is not essential for a diagnosis of Milroy disease. There can be de novo mutations in VEGFR3 and recessive transmission also can occur. Meige disease refers to familial lymphedema of the lower extremity that manifests during adolescence. “Meige disease” should not be used for patients with adolescent onset of lymphedema without a family history of the disorder [13].

Fig. 7.4

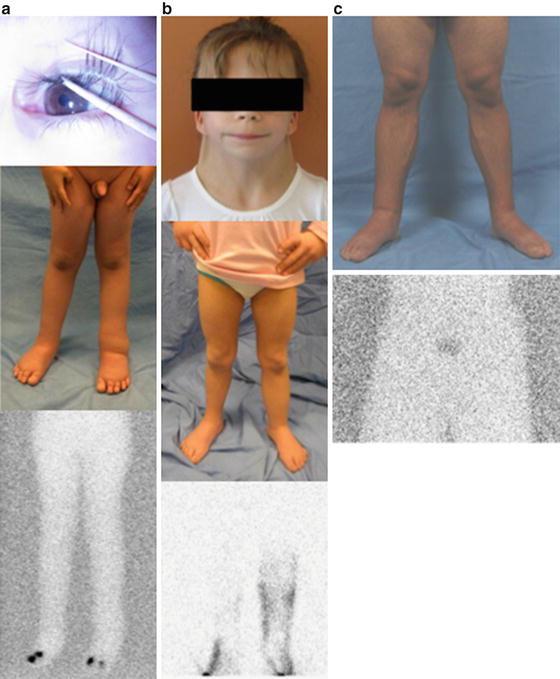

Familial and syndromic lymphedema. (a) 6-year-old male with lymphedema–distichiasis syndrome causing bilateral lower-extremity swelling. No flow of tracer to his inguinal nodes 2 h following injection. His mother also has the condition (b) 9-year-old with Turner syndrome and lymphedema of all four extremities. Lymphoscintigraphy showed delayed transit to inguinal nodes and dermal backflow on 3 h image. (c) 23-year-old with Milroy disease. The patient has lymphedema of the lower extremities and scrotum since birth, as well as a family history of the disease. The tracer has not reached his inguinal nodes 3 h after the injection

Patients with a FOXC2 mutation causing lymphedema–distichiasis have an extra row of eyelashes and may exhibit eyelid ptosis and/or yellow nails. Hypotrichosis–lymphedema–telangiectasia (SOX18 mutation) causes sparse hair, and cutaneous telangiectasias. Hennekam syndrome (CCBE1 mutation) is characterized by generalized lymphedema with visceral involvement, developmental delay, flat faces, hypertelorism, and a broad nasal bridge [8]. Patients with Turner syndrome have a 57 % percent risk of lymphedema; 76 % have onset in infancy and 19 % develop swelling during childhood or adolescence [14]. Noonan syndrome may manifest with generalized lymphedema, intestinal lymphangiectasis and/or fetal hydrops. Patients with Noonan syndrome have a 3 % risk of lymphedema [15]. Hennekam syndrome is characterized by unusual facies, seizures, lymphedema of the lower limbs, genitalia and face, intestinal lymphangiectasis, and mental retardation. Overall, a genetic cause of primary lymphedema is present in 36 % of patients’ familial disease, and in 8 % of individuals without a family history of the condition [16]. Most of the known mutations for lymphedema involve proteins involved in the VEGFR3 pathway (e.g., FLT4, GJC2, FOXC2, SOX 18, GATA2, CCBE1, PTPN14) [16].

Morbidity

Primary lymphedema is a progressive condition and there is no cure. Generally, patients with primary lymphedema have less morbidity (e.g., enlarged limb size, infections, reduced function) compared to adults with secondary lymphedema (Table 7.4). One explanation may be that patients with primary lymphedema have compensated for the lack of lymphatic function because the defect occurred during embryogenesis. Lymphedema generally is not painful; significant discomfort is inconsistent with the disease. However, as the circumferential overgrowth of the extremity worsens and the limb becomes heavier, underlying musculoskeletal symptoms can occur.

Table 7.4

Morbidity of primary lymphedema in 138 pediatric patients

Infection | Cellulitis Recurrent (>3/year) Hospitalization Chronic antibiotic prophylaxis | 18.8 % 7.2 % 13.0 % 5.1 % | (26/138) (10/138) (18/138) (7/138) |

Cutaneous | Hyperkeratosis, lymphorrea, ulceration, verrucous changes | 15.2 % | (21/138) |

Orthopedic | Gait disturbance | 5.0 % | (6/121) |

Genitourinary | Dysuria, urethritis, phimosis, spraying of urine | 16.0 % | (4/25) |

Progression | Increased volume or worsening symptoms | 57.9 % | (55/95) |

Psychosocial

The most common problem caused by lymphedema is emotional distress (Fig. 7.5). Patients have lowered self-esteem because the involved area does not look normal. Unilateral limb involvement can be more distressing than bilateral disease because the asymmetry is more noticeable. Individuals may not feel comfortable wearing clothing that exposes their diseased limb. Children may avoid changing clothes in front of their peers at school or refrain from swimming. Patients with moderate/severe disease can have significant psychosocial morbidity which negatively impacts their quality of life.

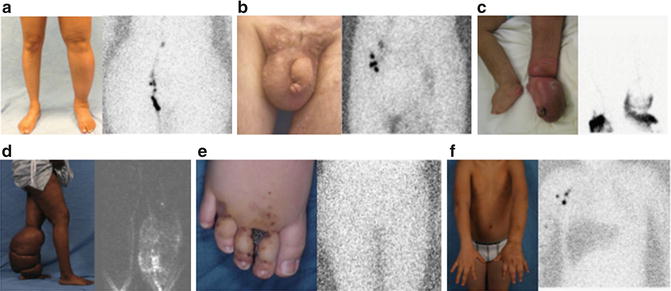

Fig. 7.5

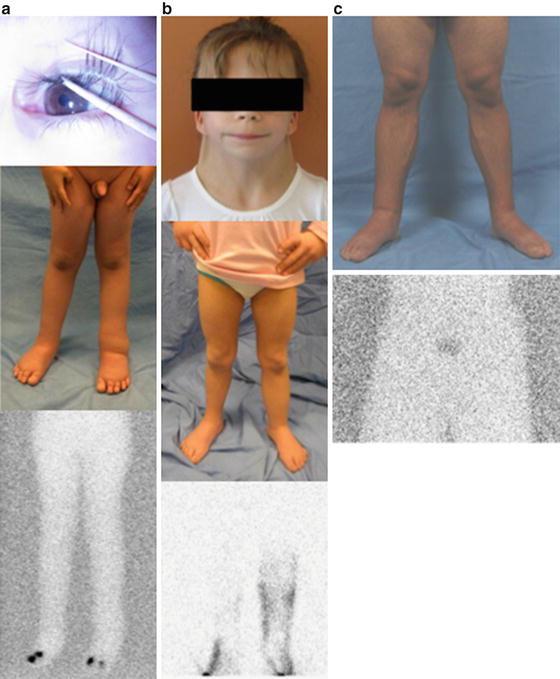

Morbidity of primary lymphedema. (a) 37-year-old female with left lower extremity lymphedema causing low self-esteem because of the asymmetry between her legs. No flow of tracer to her left inguinal nodes 2 h following injection. (b) 24-year-old male with psychosocial distress because of genital lymphedema. Absent nodal uptake of tracer on left side 3.5 h after injection. (c) 26-year-old female with lower extremity lymphedema and dermal backflow on lymphoscintigram. She has cellulitis of her left leg that required intravenous antibiotics. (d) 37-year-old female with adolescent onset lymphedema. Her disease inhibited her ability to ambulate and fit clothing. Note dermal backflow on lymphoscintigram. (e) 11-year-old male with infant-onset lymphedema and cutaneous vesicles causing bleeding, lymphorrhea, and infection. Lymphoscintigram image illustrates no flow of tracer to inguinal nodes 2.5 h following injection. (f) 12-year-old male with infant-onset left upper extremity lymphedema. He had a 3-month history of arm pain and exacerbation of this disease. Histopathology showed lymphangiosarcoma. Note absence of tracer in left axillary lymph nodes on lymphoscintigram

Infection

A lymphedematous extremity has a significantly increased risk of cellulitis compared to the non-affected limb. Lymph stagnation predisposes the area to infection after minor trauma because of: (1) impaired immunosurveillance (lymphatics function as an immunologic defense), (2) decreased oxygen delivery to the skin, and (3) a proteinaceous environment favorable for bacterial growth. Nineteen percent of patients with primary lymphedema have a history of cellulitis, 13 % have been hospitalized, and 7 % have >3 attacks each year [3]. Cutaneous infections in patients with lymphedema can spread more quickly compared to individuals without the disease. A superficial cellulitis can develop rapidly into a systemic infection and sepsis. Patients are counseled to seek medical attention quickly if they suspect an infection in a lymphedematous area. Often, individuals will carry oral antibiotics with them and administer the medication during the onset of the infection. Patients who have ≥3 episodes of cellulitis/year are placed on chronic suppressive antibiotic therapy following infectious disease consultation.

Skin Changes

Generally, patients with primary lymphedema have normal appearing skin. However, primary lymphedema can occur with other types of vascular malformations (usually capillary malformation). Because the disease is progressive, 15 % of patients will develop cutaneous problems such as bleeding from vesicles, fungal toenail lesions, hyperkeratosis, lymphorrhea, and verrucous changes [3]. Skin ulceration rarely affects patients with primary lymphedema because their arterial and venous circulations are intact. However, skin breakdown can occur in patients who also have venous insufficiency.

Orthopedic

Only 5 % of children with primary lymphedema have orthopedic problems, such as disturbance of gait or restriction of joint motion [3]. As adipose deposition increases the circumference of the affected area, patients can have difficulty using the extremity because of its weight. Individuals also may find it challenging to fit in clothes because of the soft-tissue overgrowth. The extra weight of the extremity causes the underlying muscle and bone to be hypertrophied from the added work of moving the extra subcutaneous tissue and skin [5]. Soft tissue overgrowth can be improved by removing hypertrophied tissue (e.g., suction-assisted lipectomy, staged skin/subcutaneous excision). Because lymphedema only affects the skin and subcutis, the underlying muscle and bone are not primarily affected. Consequently, axial overgrowth of the extremity does not occur and patients do not need to be monitored for a leg-length discrepancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree