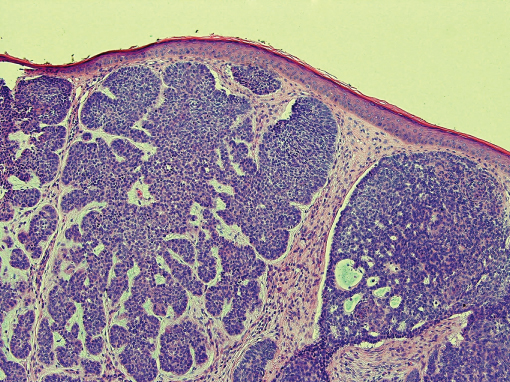

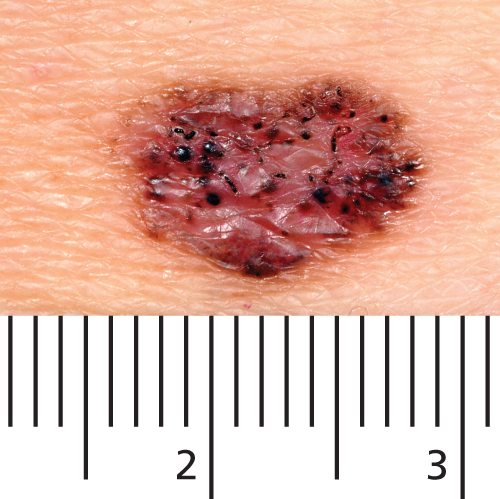

Chapter 22 Malignancies of the skin are among the most common cancers known to man. In benign tumours, there is a proliferation of well-differentiated cells with limited growth, whereas in a malignant tumour, the dysplastic cells are undifferentiated and expand in an uncontrolled manner. The carcinogenic effect of the sun is thought to play an important role in many types of skin cancer. One hundred years ago, a tanned skin indicated outdoor work. Nowadays, many individuals deliberately seek the sun for the purposes of tanning. Longer holidays, cheap flights and a fashion to be tanned may all have contributed to the doubling of melanoma incidence over the past decade. However, recently there has been an increasing global awareness concerning the dangers of strong sunlight. Public health campaigns such as ‘slip slop slap’ (‘slip on a shirt, slop on sunscreen and slap on a hat’) in Australia have been very successful at modifying people’s behaviour in the sun. High-intensity ultraviolet (UV) light can lead to sun-burning episodes in fair-skinned individuals, and this is thought to be a risk factor for melanoma, the most serious form of skin cancer. The visible nature of skin cancer means detection should be straightforward by the trained eye, although histological confirmation is essential. Early recognition of malignant skin tumours by medical practitioners is essential in order that patients suffer minimal morbidity and avoid skin-cancer-induced mortality. Actinic keratoses (AKs) occur on exposed skin, particularly in those who have worked outdoors or have been exposed to short intervals of high-intensity UV. AKs occur on the face (including the lip), dorsal hands, distal limbs and bald scalp, particularly in those with fair/sun-damaged skin and increasing age (Figure 22.1). Clinically, their appearance varies from a rough area of skin to a raised keratotic lesion. The edge is irregular and they are usually less than 1 cm in diameter. Histologically, AKs have altered keratinisation, which may lead to dysplasia and eventually invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Malignant change may be suspected in an AK that suddenly grows rapidly, becomes painful or inflamed. Figure 22.1 Sun-damaged skin with multiple actinic keratoses. Treatment with liquid nitrogen (cryotherapy) by a medical practitioner is usually effective for individual lesions with cure rates of around 70% (see Chapter 23). Various topical preparations that can be applied by patients themselves are currently available. 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) 5% cream (Efudix®) and 0.5% solution (Actikerall) are useful in treating large areas of sun-damage with multiple AKs, and is applied once daily for 4–6 weeks. The 5-FU kills any dysplastic keratinocytes and therefore produces brisk inflammation at the application site. Patients may therefore need to stop using the cream for a few days during the treatment course if discomfort is severe. Currently, 5-FU appears to be the most cost-effective treatment for AKs. Imiquimod 5% (Aldara®) is an immunomodulatory preparation that recruits immune cells to the area of skin where it is applied, which then attack the dysplastic cells. Imiquimod is applied three times a week for 4 months. 3.75% imiquimod (Zyclara) has recently been launched and should be used daily for 2 weeks, 1 week off and then treatment repeated for a further 2 weeks. There is some evidence that memory T-cells are induced by this therapy, resulting subsequently in lower numbers of clinical AKs. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory diclofenac (Solaraze®) has been shown to be effective against small AKs if it is used regularly twice daily for 3 months. This treatment seems to produce less skin irritation than 5-FU or imiquimod. Ingenol mebutate gel (Picato®) is a recent addition to the treatment choice for actinic keratosis. It is a cytotoxic agent derived from Milk Weed plants that is formulated in two concentrations 0.015% (for the face once daily for 3 consecutive days) and 0.05% (for the trunk and limbs once daily for 2 consecutive days). Its effects are mediated by a brisk inflammatory reaction at the site, and the rates of clearance are reported between 34% and 42%. At 1 year follow-up, relapse rates are reported to be around 50%. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) (see Chapter 24) has been shown to be as effective as 5-FU in the treatment of AKs. PDT is carried out by a medical practitioner rather than the patients themselves and can treat large areas of skin. The main limitation of PDT is usually the patient’s ability to tolerate the burning pain felt in the skin during delivery of the treatment. Any lesions not responding to the above measures should be biopsied to check for invasive malignancy. Bowen’s disease is SCC in situ; SCC occurs in the epidermis with no evidence of dermal invasion. Bowen’s disease is more common in the elderly and is seen most frequently on the trunk and limbs. Risk factors for Bowen’s disease include solar radiation, human papillomavirus warts (HPV 16), radiotherapy, ingestion of arsenic in ‘tonics’ and exposure to chemicals. Clinically, Bowen’s disease is characterised by well-defined, erythematous patches with slight crusting (Figure 22.2). Lesions enlarge slowly and may reach up to 3 cm in diameter. After many years, invasive carcinoma may develop. Bowen’s disease may be confused with a patch of eczema or superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a similar process occurring on the glans penis or prepuce. Figure 22.2 Bowen’s disease Skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis histologically. Management includes excision, curettage and cautery, cryotherapy, 5-FU, imiquimod 5% and PDT (see Chapters 23 and 24). This is the most common cancer in humans with a lifetime risk of around 30%. Known risk factors for BCC include increasing age, fair skin, high-intensity UV exposure, radiation, immunosuppression, previous history of BCCs and congenital disorders such as Gorlin’s syndrome. Sun-exposed skin in the ‘mask area’ of the face is most frequently affected. Typically, lesions start as small papules that slowly grow. Lesions often have a ‘pearly’ shiny translucent quality. Colour varies from clear to deeply pigmented. The tumour is composed of masses of dividing basal cells that have lost the capacity to differentiate any further. As a result, no epidermis is formed over the tumour and the surface breaks down to form an ulcer, the residual edges of the nodule forming the characteristic ‘rolled edge’. Once the basal cells have invaded the deeper tissues the rolled edge disappears. Nodular lesions appear as small papules or nodules with a rolled edge (Figure 22.3) and frequently a central depression that may become ulcerated. The nodules are pearly and may have dilated telangiectatic vessels on their surface. The histological features of BCC show collections of basaloid tumour cells (Figure 22.4), the pattern of which determines the histological type (i.e. nodular, superficial, morphoeic, cystic, etc.). Determining the tumour type histologically prior to definitive treatment ensures that the most appropriate management plan can be devised for each patient. If the initial tumour is incompletely excised/inadequately treated then the BCC can recur (Figure 22.5). Many BCCs on the face are now treated routinely with Mohs’ micrographic surgery to ensure that the tumour is fully resected (see Chapter 23) at the primary procedure. Figure 22.3 Nodular-type basal cell carcinoma above the eye. Figure 22.4 Nodular basal cell carcinoma histology. Figure 22.5 Recurrent nodular basal cell carcinoma. Superficial lesions appear as an erythematous patch on the skin, often on the trunk. They may be mistaken for a patch of eczema or tinea, but are not usually pruritic and slowly enlarge (Figure 22.6). A firm ‘whipcord’ edge may be present. Figure 22.6 Superficial basal cell carcinoma. Pigmented lesions can lead to confusion with naevi, seborrhoeic keratoses and melanoma (Figure 22.7). Figure 22.7 Pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Morphoeic or sclerosing type appears as a superficial atrophic scar in the skin. There is loss of the normal skin markings and the edge is usually indistinct (Figure 22.8). This can lead to incomplete excision of these infiltrative BCCs and therefore Mohs’ micrographic surgery may be indicated (see Chapter 23) to ensure surgical cure. Figure 22.8 Morphoeic basal cell carcinoma. The growth pattern determined histologically usually guides management, so most tumours are biopsied prior to definitive treatment. The site and the size of the BCC, co-morbidities and patient preference all guide what treatment option is most suitable. Treatment options include excision (including Mohs’ micrographic surgery), excision and grafting, curettage and cautery, radiotherapy, cryotherapy, imiquimod 5% and PDT for large superficial BCCs (see Chapters 23 and 24). For advanced or metastatic BCCs unsuitable for surgery/radiotherapy oral Vismodegib (Erivedge™) 150 mg daily can be taken. Erivedge has been shown to shrink 30–40% of tumours by blocking the abnormal signalling found in the Hedgehog pathway (present in 90% of BCCs). Decisions as to the optimum therapy for each individual patient is complex and is therefore frequently discussed with the patient at a multidisciplinary skin cancer meeting including dermatologists, plastic surgeons, oculoplastic surgeons, oncologists and specialist cancer nurses. As a general rule, surgical scars will improve with time compared to radiotherapy sites which tend to deteriorate cosmetically. Mohs’ micrographic surgery is becoming the ‘gold standard’ for complete excision of BCCs on the face/scalp, particularly those near the eyes and other vital structures where identifying clear tumour margins is essential to preserve normal tissue and function. Large nasal tip lesions may be more optimally treated with radiotherapy as this can be a difficult site for grafting.

Premalignant and Malignant

Skin tumours

OVERVIEW

Introduction

Premalignant skin tumours

Actinic keratoses

Management

Bowen’s disease

Malignant skin tumours

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

BCC types

Management of BCC

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree