Plaques

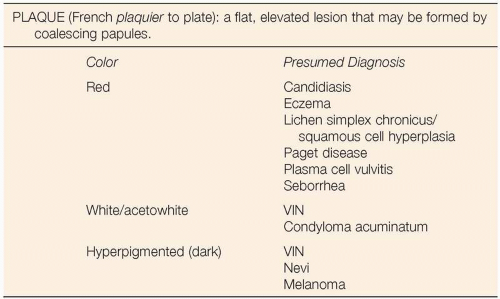

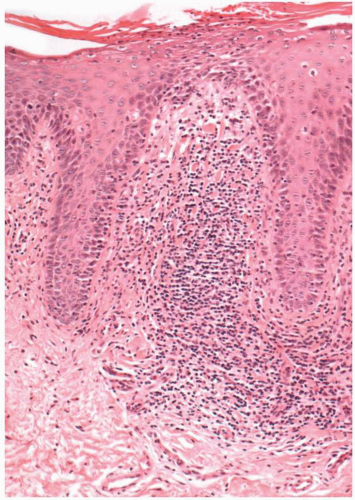

Figure 6.3. Fungal infection. This erosion has acute inflammatory cells in the superficial epithelium, where fungal organisms were identified. |

DEFINITION

Candidiasis is a fungal infection most commonly caused by Candida albicans.

GENERAL FEATURES

Vulvar candidiasis is a fairly common external manifestation of an internal vaginal infection with candida organisms. Rarely does one see an external infection without a concomitant internal vaginal infection. Candidiasis is often seen in patients who have an altered immune system, such as is noted in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals. Patients with diabetes will have frequent bouts of candidiasis, especially if the diabetes is under poor control. Women will develop candidiasis frequently after taking antibiotic therapy for extragenital infections such as pharyngitis, otitis, and cystitis. Antibiotic therapy will alter the normal flora of the vagina and allow overgrowth of candida species, resulting in vaginitis and vulvitis.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients with vulvar candidiasis will most commonly present with a complaint of an intense vulvar pruritus. There may also be an associated vaginal discharge. The vulva will be intensely erythematous and will often demonstrate a white adherent film. This white film overlying an erythematous base may appear suggestive of Paget disease. The medical history may not contain a history of diabetes. Because vulvar candidiasis may be the initial manifestation of occult diabetes mellitus, consideration should be given to obtaining a blood glucose assay on patients with intense vulvar candidiasis or recurrent vulvar candidiasis. A patient who gives a recent history of antibiotic usage with resultant candidiasis does not routinely need a blood glucose assay. Nor would it be imperative to obtain HIV serostatus on such an individual. However, if no risk factors are noted for the development of recurrent candidiasis and a blood glucose assay is normal, consideration should be given to obtaining an HIV assay, after appropriate counseling.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Erythematous vulvar candidiasis must be differentiated from Paget disease, eczema (lichen simplex chronicus [LSC]), psoriasis, and reactive vulvitis. Discovery of hyphae on potassium hydroxide (KOH) smears from the vagina and or vulva will almost always resolve this point of differential diagnosis. Paget disease is rarely as diffuse as vulvar candidiasis and requires biopsy for diagnosis. Psoriasis will usually demonstrate a scaly appearance. LSC will be more hyperplastic and less diffuse, but may be associated with chronic and recurrent vulvar candidiasis. A reactive vulvitis will usually be associated with an antecedent history suggestive of recent use of an irritative substance on the vulva.

CLINICAL BEHAVIOR AND TREATMENT

Efforts to clear candida vulvitis will be unsuccessful if the patient has undiagnosed and untreated diabetes mellitus. Persistence of vulvitis in spite of adequate therapy should prompt blood glucose evaluation and control of the blood glucose, if it is elevated. Patients who are taking recurrent or long-term antimicrobial therapy for extragenital disease should be forewarned that persistent and recurrent candidiasis may be a complication and antifungal therapy should be instituted at the earliest exhibit of symptoms.

Numerous antifungal preparations exist to treat vaginal candidiasis; if these are ineffective, consideration should be given to culturing for a resistant strain of fungus such as Torulopsis glabrata. Such infections may require topical application of gentian violet 1% solution or boric acid powder (600 mg in 0 gelatin capsules) intravaginally once daily for 10 to 14 days. With failure

of topical therapies to alleviate recurrent candidiasis, consideration should be given to oral ketoconazole (Nizoral) at a dose of 200 mg daily. Therapy should be discontinued after alleviation of symptoms, and the patient should be observed closely for evidence of hepatotoxicity induced by ketoconazole.

of topical therapies to alleviate recurrent candidiasis, consideration should be given to oral ketoconazole (Nizoral) at a dose of 200 mg daily. Therapy should be discontinued after alleviation of symptoms, and the patient should be observed closely for evidence of hepatotoxicity induced by ketoconazole.

A useful agent for treating vulvar candidiasis is a combination of clotrimazole and betamethasone (Lotrisone cream). The steroid component of the topical cream will reduce inflammation and the desire to scratch, and the clotrimazole exerts an antifungal activity. The cream should be used twice daily for approximately 2 weeks.

PROGRESSIVE THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Progressive therapeutic options are as follows:

Treat vaginal candidiasis with over-the-counter or prescription antifungal preparations. Apply clotrimazole and betamethasone (Lotrisone) to the vulva twice daily for 10 to 14 days.

For recurrent disease (and a negative glucose screen, negative oral antibiotic history, and negative HIV screen):

Gentian violet 1% painted on the vagina and vulva weekly for approximately three episodes. Patients should be forewarned that clothing may be stained and that occasionally a reactive vulvitis may be noted.

Boric acid vaginal suppositories (600 mg in a 0 gelatin capsule) once or twice daily. Therapy may be continued for several weeks; however, irritative symptoms may prompt discontinuation.

Oral ketoconazole (Nizoral) at 200 mg PO daily to be discontinued after 2 to 4 weeks in the face of resolution of symptoms. If therapy is continued longer, the possibility of hepatotoxicity increases and liver function tests should be followed closely.

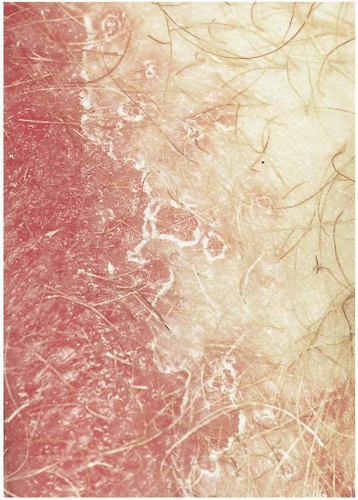

Figure 6.4. Moderate erythema in patient who complained of pruritus for 3 years. The clinical impression was eczema, and the patient was advised to use hypoallergenic soap. The condition resolved. |

DEFINITION

Eczema, with a name derived from the Greek word ekzein (to boil out), is an inflammatory dermatologic disease, often of indeterminant etiology with acute, subacute, and chronic manifestations, most commonly presenting as a pruritic rash.

GENERAL FEATURES

Eczema may well be the most common inflammatory skin disease. The vulva is not a common site of eczema; however, pruritic vulvar rashes are common and an understanding of the evolution of acute eczema into chronic eczema is important for the clinician. Acute eczema is most commonly a manifestation of direct contact with an allergen. The classic example of this condition is the contact dermatitis noted after exposure to poison ivy. This process is self-limited; however, other allergens, either exogenous or endogenous, may result in a subacute inflammation, which eventually evolves into a chronic eczematous pattern associated with self-induced trauma secondary to intense scratching of pruritic vulvar skin. Often the inciting agent for the pruritus is unknown.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The typical patient with vulvar eczema will present with a complaint of intense vulvar pruritus. This discomfort may have been present for weeks to years. Rarely, a patient exposed to an allergen such as poison ivy or poison oak will present in the acute phase complaining of pruritus, but the phase of acute eczema secondary to such contact is rarely seen. Most commonly the subacute and

chronic phases of eczema will be observed by the clinician. Whereas acute eczema is a vesicular eruption associated with erythema, the subacute and chronic phases are associated with erythema and scale with nondescript borders. Persistence of inflammation and irritation, especially associated with scratching, will result in a plaquelike disease process with thickened skin and prominent skin markings. Rarely is it necessary to perform a biopsy to arrive at a diagnosis.

chronic phases of eczema will be observed by the clinician. Whereas acute eczema is a vesicular eruption associated with erythema, the subacute and chronic phases are associated with erythema and scale with nondescript borders. Persistence of inflammation and irritation, especially associated with scratching, will result in a plaquelike disease process with thickened skin and prominent skin markings. Rarely is it necessary to perform a biopsy to arrive at a diagnosis.

MICROSCOPIC FINDINGS

The histopathologic features of atopic dermatitis, seborrhea dermatitis, dyshidrosis, and atopic eczema are essentially identical. Acute spongiotic dermatitis with intraepithelial edema is an early feature and may be associated with vesicles. Subacute changes may be seen with a lymphocytic infiltrate within the epithelium, as well as in the papillary and superficial dermis. The diagnosis of contact (irritant) dermatitis should be considered if eosinophils are present. When the change is severe, allergic contact dermatitis should be considered.

ADJUNCTIVE STUDIES

No adjunctive studies are necessary to discern the etiology of this process.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The condition most commonly confused with eczema is psoriasis. Psoriasis generally has a much more intense erythema and discrete borders associated with silvery white scales. Psoriasis may also be found in rather characteristic extragenital areas such as the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees and in prior incisional sites. Such findings would lend support to a diagnosis of psoriasis without the necessity to perform biopsy. Seborrhea may also be confused with eczema in the vulvar region. Seborrhea is particularly noted in such anatomic locations as the scalp and the face (eyebrows, nasolabial folds, ear canals and posterior auricular folds, and presternal area). These areas will demonstrate a fine, whitish scale over an erythematous base. Borders will appear nondescript. Often it may be impossible to differentiate on clinical grounds the rashes of eczema, psoriasis, and seborrhea.

CLINICAL BEHAVIOR AND TREATMENT

Acute eczema, secondary to contact allergy, requires control of pruritus primarily. This may be accomplished initially with cool, wet dressings containing Burow solution. Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or hydroxyzine (Atarax) may be administered to relieve pruritus. Although topical steroid-containing creams may be applied to relieve itching, significantly greater relief may be obtained by administering oral prednisone in high doses for short periods. Twenty to 30 mg prednisone taken twice daily for 7 to 10 days in adults will have significant anti-inflammatory action and will contribute markedly to relief of the patient’s pruritus. If evidence of infection is present (perhaps as a result of scratching), oral antibiotics with activity against coagulase-producing staphylococci should be administered.

When dealing with a subacute or chronic eczema, efforts should be made to define an allergen and remove the allergen from contact with the patient’s vulva. Such substances may be included in synthetic clothing materials or perhaps feminine hygiene products. Patients may be advised to wear no undergarments until severe symptoms subside. Often this will result in significant relief of symptoms. Topical steroids such as medium-strength betamethasone 0.1% (Valisone) may be applied 2 to 3 times daily for 2 weeks with subsequent tapering of frequency of application. Weaker steroid preparations can be used, such as triamcinolone 0.1% (Kenalog). Ointments applied after showers or bathing will help seal in moisture and improve hydration of the skin. Lotions such as Keri lotion, Nutraderm, and Nutraplus may also be of assistance. Similar preparations are found in cream form. Soaps should be mild and hypoallergenic. Plaquelike chronic lesions unresponsive to topical steroids may require intralesional injection with triamcinolone (Kenalog-10). Because long-term steroid applications may cause skin atrophy, the patient with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis may benefit from topical applications of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment (Protopic) twice daily. If tacrolimus is used, patients should be warned that the most common side effect is skin irritation (burning), which will usually decrease after the first week of therapy. Tacrolimus is an immunosuppressant, and care should be taken in deciding to administer it to patients with a prior history of herpes simplex or human papillomavirus (HPV), to avoid recurrence.

PROGRESSIVE THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Progressive therapeutic options are as follows:

Hydration and lubrication of the skin with such creams and lotions as Keri, Nutraderm, or Nutraplus. Avoid frequent bathing with drying soaps and instead use hypoallergenic soaps such as Dove, Keri, or Lowilla.

For subacute and chronic eczema, topical steroids such as 0.1% betamethasone (Valisone) applied 2 to 3 times daily for 2 weeks, with subsequent tapering to less frequent application or to a weaker

steroid preparation, such as triamcinolone 0.1% (Kenalog).

For subacute and chronic eczema with moderate to severe symptoms, topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment twice daily. (Warn about burning and consider alternative therapy in patients with history of herpes simplex virus or HIV to decrease risk of reactivation.)

Antibiotic therapy directed against coagulase-producing staphylococcal organisms, if evidence of cellulitis is present (amoxicillin/clavulanate [Augmentin] 250 mg three times a day in non-penicillin-allergic patients).

Intralesional infection of triamcinolone (Kenalog-10) with a small-gauge needle.

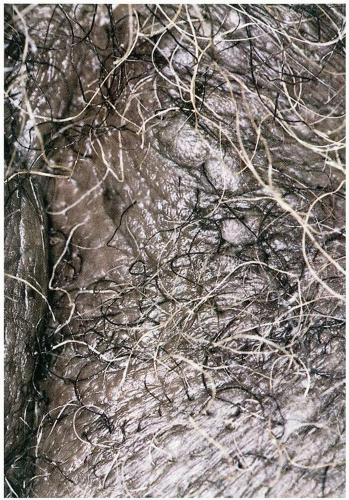

LICHEN SIMPLEX CHRONICUS AND SQUAMOUS CELL HYPERPLASIA (Figures 6.6., 6.7., 6.8., 6.9., 6.10., 6.11. and 6.12.)

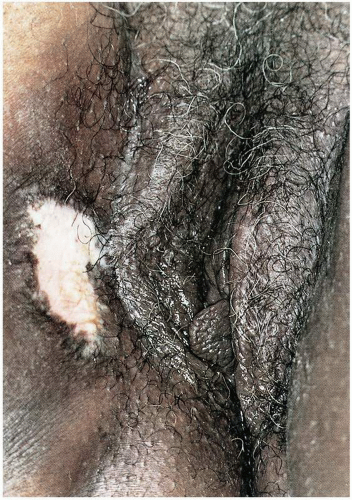

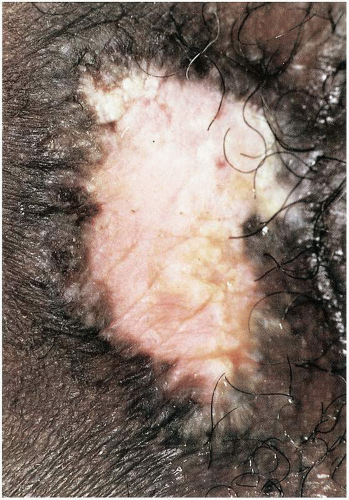

Figure 6.6. Pruritic, hypertrophied plaque of squamous cell hyperplasia/lichen simplex chronicus, managed with Valisone 0.1% ointment with resolution of symptoms. |

DEFINITION

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic eczematous inflammation that results in thickened skin and often associated with excoriation and fissures. It is characterized by acanthosis with a prominent superficial dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate. The term squamous cell hyperplasia is used by some to describe a non-specific thickening of vulvar epithelium characterized by acanthosis without a significant dermal inflammatory component. The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), that initially introduced the term squamous cell hyperplasia, now recommends that such cases be included under the term lichen simplex chronicus. The terms replace the ISSVD’s prior term hyperplastic dystrophy.

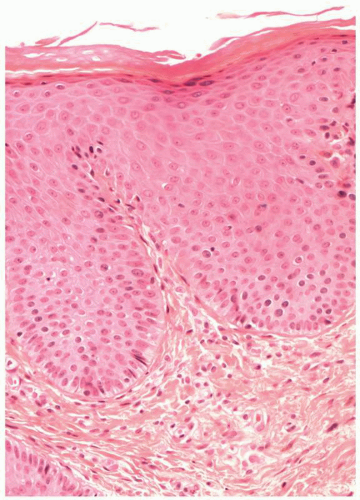

Figure 6.7. Magnified view of plaque of squamous cell hyperplasia/lichen simplex chronicus, biopsy confirmed. There is associated postinflammatory hypopigmentation. |

GENERAL FEATURES

LSC can be a primary dermatosis, or secondary, presenting as a reaction to another vulvar disease such as lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), and some other disorders. Both primary and secondary LSC are observed most frequently in adults. Primary LSC is the more common condition and may be a consequence of exposure to an irritating or inflammatory agent such as laundry products or occlusive underwear fabrics. Usually the inciting agent will remain undetermined. It may be related to stress. No known etiology for the condition has been determined; however, chronic irritation is a factor and some patients derive localized relief or comfort from scratching the extremely pruritic regions. This scratching leads to persistence of the localized area of inflammation.

This condition is relatively common in the vulva, where cases interpreted only as squamous cell hyperplasia on biopsy are uncommon.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients with vulvar LSC usually present complaining of moderate to severe pruritus that is typically fairly well localized on the labial skin. Pruritus is the usual presenting symptom. This symptom at this region will have been present for weeks or months. The patient will often describe an inability to sleep because of the intense desire to scratch the pruritic region. Scratching may lead to secondary infection. On examination, plaquelike, white epithelium will be noted. The contour will be irregular. The disease is usually unilateral. Consideration that the LSC may be secondary to a possible underlying vulvar disease, such as lichen sclerosus, will assist in establishing the

correct diagnosis. Confirmation of diagnosis will require biopsy.

correct diagnosis. Confirmation of diagnosis will require biopsy.

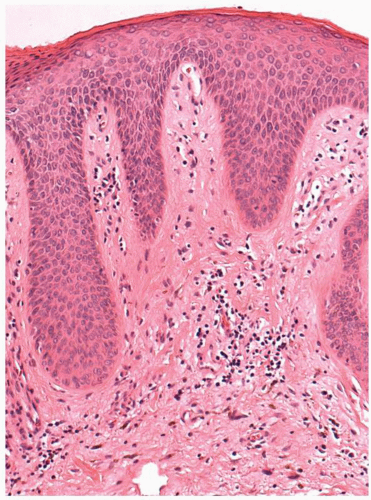

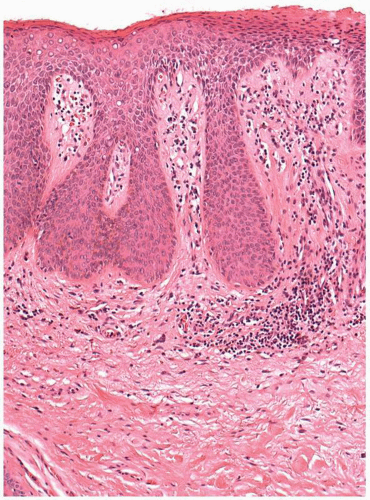

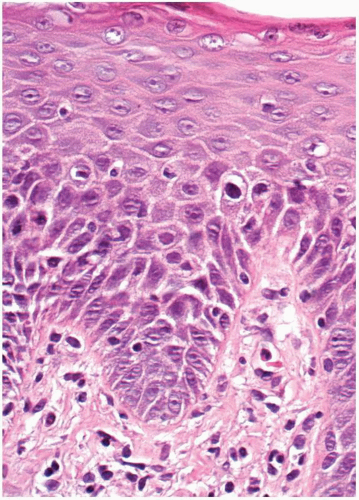

MICROSCOPIC FINDINGS

LSC is characterized by prominent acanthosis with elongation, widening, and deepening of the rete ridges and thickening of the epidermis. Hyperkeratosis may be present, but there is no epithelial atypia. Within the superficial dermis, immediately beneath the epithelium, superficial dermal collagenization may be present. There typically is an associated mild chronic superficial dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis may be present. Superficial erosion with associated inflammatory cell exocytosis may be evident, secondary to scratching. The term squamous cell hyperplasia has been limited to cases in which all of the above findings may be present except that the inflammatory infiltrate is absent.

When inflammatory cell exocytosis is present within the epithelium, silver stain for fungus and periodic acid- Schiff (PAS) are of value to evaluate for fungal infection. In those cases demonstrating significant epithelial atypia, VIN and Paget disease should be considered.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Certain monilial, candida, and dermatophyte infections may demonstrate similar epithelial changes and should be excluded. Candida infections are of a more immediate duration than observed with LSC. Usually there will be concomitant vaginal candidiasis. Wet mount to search for fungal organisms assists in making the proper diagnosis.

Other conditions to be considered to determine if the LSC is primary or secondary include evaluation for psoriasis, lichen sclerosus, VIN, and Paget disease. Lesions seen with psoriasis are more sharply demarcated, and evidence of psoriasis may be present in extragenital locations such as the extensor surfaces of the arms.

Plaquelike white epithelium on the vulva may be consistent with a hyperplastic variety of lichen sclerosus. In such cases there will be the usual stigmata of lichen sclerosus observed diffusely around the hyperplastic epithelium. Associated agglutination of the labia minora and partial or complete obscuring of the clitoris related to agglutination of the frenulum or prepuce may be seen. Patients with lichen sclerosus will not demonstrate the scaly appearance that may be seen with LSC, but an occasional patient with lichen sclerosus will have adjacent squamous hyperplastic and hyperkeratotic features, sometimes associated with differentiated VIN.

Plaquelike white epithelium may also be noted in patients with VIN. This process will usually be multifocal, although not invariably. Examination of the vulva after topical 3% to 5% acetic acid and visualization with a colposcope or other well-lighted magnification will demonstrate this multifocal pattern. Biopsy will be necessary and is usually diagnostic.

The identification of the presence of associated specific dermatologic conditions, such as psoriasis and lichen sclerosus, establishes that the LSC is secondary and directs the therapy primarily to the underlying vulvar disease. Biopsy will be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and distinguish these conditions.

CLINICAL BEHAVIOR AND TREATMENT

LSC can be cured only if the itch-scratch cycle is terminated. Repetitive scratching leads to persistence of irritation and subsequent itching. Patients must be advised strongly to avoid scratching the lesion. Efforts should be made to determine what agents may be the etiologic factors. Alterations in laundry products and avoidance of synthetic underwear and any other possible contact irritants may be of assistance. Occasionally it may be necessary to have patients wear cotton gloves at bedtime to decrease trauma induced by subconscious scratching while asleep. If stress is a significant component of the patient’s symptomatology, emphasis should be placed on alleviating this stress with behavioral modification and appropriate counseling.

Extremely hypertrophied skin may require moderate to superpotent steroid application in the form of ointments. Moderate-strength ointments such as betamethasone 0.1% (Valisone) may be tried initially. The ointment may be applied twice daily until symptoms are controlled, usually in 10 to 14 days. Use thereafter will be episodic. If no response is noted, a trial of superpotent steroid such as clobetasol 0.05% (Temovate) may be used for short periods. If no response is noted to topical applications of steroids, it may be necessary to use intralesional injections of triamcinolone (Kenalog-10). If evidence of infection is present, oral antibiotics directed at common organisms such as staphylococci may be administered to decrease the infectious irritation. Because LSC is a variant of eczema, consideration may be given to using the topical immunosuppressant tacrolimus 0.1% ointment twice daily in patients with moderate to severe symptoms. Patients should be warned of the potential for burning, which usually resolves after 1 week of continued use.

PROGRESSIVE THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Progressive therapeutic options are as follows:

Topical steroid ointment with emphasis on lowest effective potency. For markedly hyperplastic skin it may be necessary to use moderate-strength steroids such as betamethasone 0.1% ointment (Valisone). Decrease to a lower strength steroid preparation after 2 weeks, especially if the condition involves the intertriginous folds.

High-potency topical steroids such as clobetasol (Temovate) applied twice daily until symptoms are controlled and then tapered to sparing use of a less potent steroid.

Tacrolimus 0.1% ointment twice daily (warn about potential irritation and burning). Also, consider other alternatives in patients with a history of herpes simplex or HPV to decrease risk of reactivation).

Intense behavioral modification for patients demonstrating stress-related or stress-induced LSC. In addition to counseling, patients must be advised not to scratch pruritic vulvar lesions.

Intralesional injection with triamcinolone (Kenalog-10).

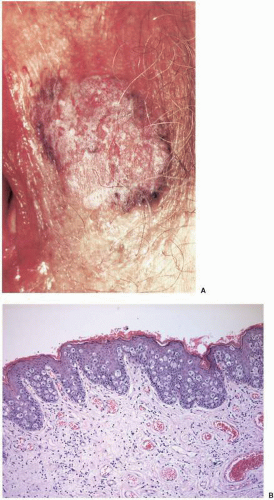

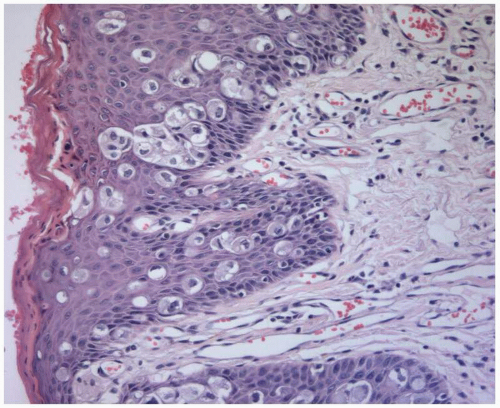

Figure 6.14. Paget disease. Paget cells are present in the basal and parabasal areas. A few isolated Paget cells are in the superficial epithelium. |

DEFINITION

Paget disease is an intraepithelial neoplasm of cutaneous glandular, or noncutaneous, origin associated with proliferation of neoplastic cells characterized by eczematoid changes of the involved epithelium. The etiologic classification of vulvar Paget disease by Wilkinson and Brown (2002) is summarized in Table 6.1.

GENERAL FEATURES

Paget disease is primarily a disease of postmenopausal women, most commonly Caucasian women. It accounts for approximately 2% of vulvar neoplasms. The original description of Paget disease pertained to breast adenocarcinoma. It was later observed that Paget disease could occur in extramammary locations, primarily the vulva. Paget disease of the breast is always associated with underlying intraductal or invasive adenocarcinoma of the breast; Paget disease of the vulva is not and, in fact, is usually only intraepithelial. Vulvar Paget disease may be of cutaneous or noncutaneous origin, as defined in the 2002 classification of Wilkinson and Brown. Cutaneous Paget disease is the more common form and is associated with adenocarcinoma of the vulva in fewer than 25% of cases. Cutaneous Paget disease may be associated with invasive Paget disease or related to an underlying adenocarcinoma of the vulva of glandular or skin appendage origin. Paget disease of the noncutaneous type arises from nonvulvar sites but secondarily involves the vulva, presenting as Paget disease. This may be observed in patients with Paget disease of urothelial cell (transitional cell) carcinoma of the bladder, gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma (rectal or anorectal), or other noncutaneous site adenocarcinomas, including the cervix.

Table 6.1 Etiologic Classification of Vulvar Paget Disease of Cutaneous and Noncutaneous Origin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||