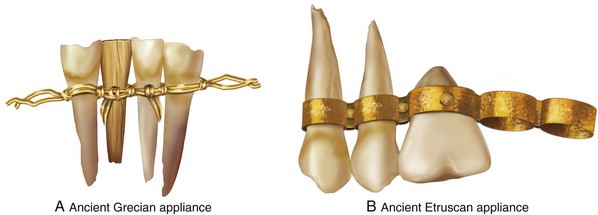

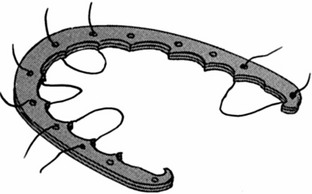

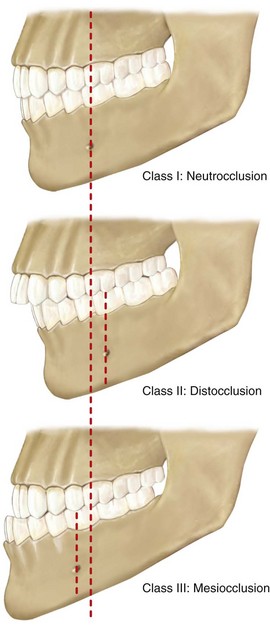

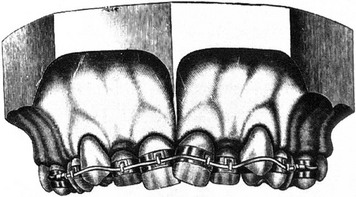

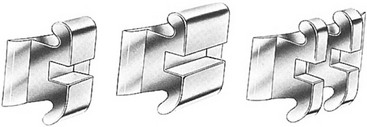

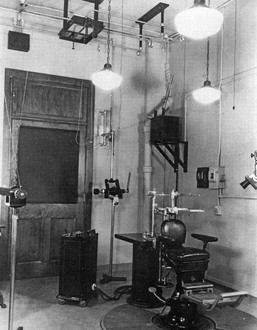

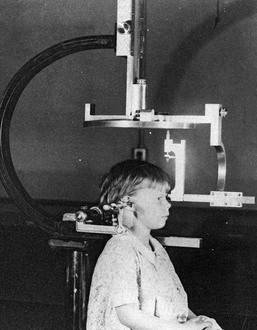

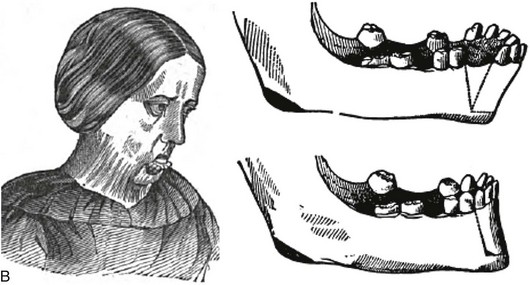

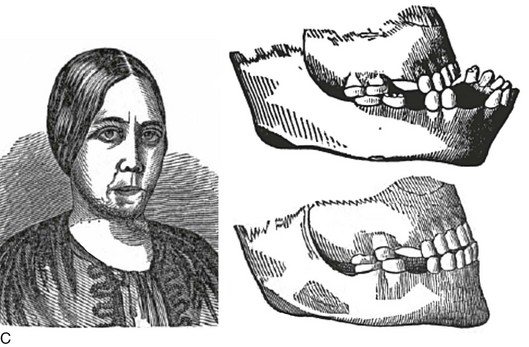

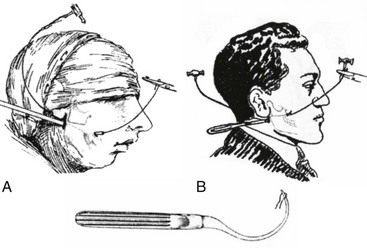

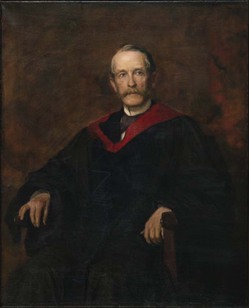

2 • Pioneers in the Field of Orthodontics • Early Pioneers in the Field of Orthognathic Surgery • Hugo L. Obwegeser: Development of the Standard Orthognathic Procedures • William H. Bell: Experimental Studies to Confirm the Biologic Basis of the Standard Orthognathic Procedures • Hans G. Luhr: Development of Plate and Screw Fixation for Craniomaxillofacial Surgery • Paul Louis Tessier: Development of Craniofacial Surgery Orthodontic appliances that are somewhat primitive but surprisingly well-designed for their time have been found in Ancient Greek written materials.8 Four Etruscan specimens of young adult women dating back to 900 B.C. that specifically demonstrate appliances on the teeth have also been recovered.23,208 The orthodontic type appliances are gold bands around teeth that are adjacent to an edentulous gap. The appliances appear to be for the purpose of managing the space left by tooth loss earlier in life (Fig. 2-1).209 In addition, the Ancient Greek scholars Hippocrates and Aristotle both have writings that discuss various ways to straighten teeth and to treat various dental conditions.20,51 Knowledge of dental extractions carried out for the purpose of mechanically straightening the remaining teeth was also reported by Leonardo da Vinci during the High Italian Renaissance.166 The bandolet or bandeau, which was created in 1723 by Pierre Fauchard of France, was the first documented dental arch expansion appliance (Fig. 2-2).202 It consisted of a heavy maxillary labial arch wire to which the teeth were ligated.202 The term orthodontia is said to have been coined in 1841 by Lafoulon, and it appeared in the book about malocclusion written by J.M. Alexis Schange.11,157,203 Figure 2-1 A, A drawing of the anterior mandibular dentition in a mummy specimen from ancient Greece (approximately 1000 B.C.) currently housed in the Archaeological Museum in Athens, Greece. A gold wire was used to tie teeth together and to band others to support replacements. The use of human, animal, carved wood, bone, or ivory for replacement teeth was practiced by the ancient Grecian society. B, A drawing of an ancient Etruscan orthodontic appliance found on the maxilla of a mummy in a tomb (approximately 700 B.C.), which is currently at the Civic Museum in Cornet, Italy. It demonstrates gold soldered rings and rivets to hold dental replacements as a bridge. The specimen has two natural teeth, one riveted oxtooth and four spaces for others Figure 2-2 Illustration of the “bandolet” bandeau, which was created in 1723 by Pierre Fauchard of France. This was the first documented dental arch expansion appliance. In 1858, perhaps the first formal article on orthodontics published in a medical journal was written by Norman W. Kingsley (Fig. 2-3). By the 1880s, Norman Kingsley’s Treaties on Oral Deformities as a Branch of Mechanical Surgery systematically described the current techniques of the day for the repositioning of teeth (Fig. 2-4).109 Kingsley was among the first to fully describe how extraoral forces (e.g., headgear) could be used to correct protruding maxillary anterior teeth. His emphasis was primarily on the alignment of the anterior maxillary teeth in an attempt to improve facial appearance. To Kingsley, the extraction of teeth for the purpose of uncrowding and to reduce the protraction of the incisors was acceptable practice. Details of how the upper and lower teeth articulated with each other (i.e., occlusion) were of secondary importance. He used a wide variety of apparatus to reposition the anterior teeth, including wires, bands, custom palatal plates, elastics, wedges, linen twine, rubber tubing, leathers, gold bands, and vulcanite. Impressions of the teeth and dental models were used during planning and for the precontouring of labial placed wires. The use of an external apparatus placed over the top of the head and then either secured to the chin or held with bands secured to the maxillary incisors became part of his everyday practice (Fig. 2-5). Figure 2-4 Norman Kingsley’s text entitled A Treatise on Oral Deformities as a Branch of Mechanical Surgery, which was published in 1880. Figure 2-5 Headgear designed and used by Norman W. Kingsley. According to Kingsley, “I sat to work to make an apparatus that would pull the lower jaw back. As you can see from the photograph taken at the time she was wearing the apparatus, it consists of two parts. For the lower part, I made a brass plate to fit the chin, having arms with hooked ends reaching to a point just below the point of the chin. These arms were arranged in such a way that the distance between them could be altered at will by simply pressing them apart or to gather. The upper part consisted of a simple network going over the head and having two hooks on each side, one hook being above and the other below the ear. When the apparatus was completed and in use, there were four ligatures of ordinary elastic rubber pulling in such a way as to force the lower jaw almost directly backward.” From Kingsley NW: A treatise on oral deformities as a branch of mechanical surgery, London, 1880, H.K. Lewis, pp 137, Figure 68. Kingsley’s basic principles for the mechanical alignment of the teeth can be summarized as follows: • The positioning of the six maxillary anterior teeth with regard to each other and in relationship to the lip is essential for facial aesthetics. • The contact of a certain number of maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth, at least on one side, is important for the grinding and mastication of food. • All other teeth are potentially expendable, depending on the effort required by the clinician for straightening and the individual’s desire to maintain them. • From both a mastication and an aesthetic perspective, there is no particular need for the maintenance of all 32 teeth or to achieve a specific and detailed way of the upper and lower teeth occluding with one another. Dr. Kingsley also commented on facial aesthetics, stating that “the eye soon tires of the stiffness and formality of unbroken uniformity, and is only permanently pleased with the beauty which comes from graceful variation.”109 He acknowledged the occurrence of jaw deformities when he said that “[a] lack of harmony between the maxilla and mandible is occasionally seen. For instance, when the mandible is very large and massive or unusually small in comparison to the upper jaw. When present, this will interfere with the harmony of the surrounding parts of the face.”109 In 1897, J.N. Farrar published a two-volume illustrated text entitled A Treatise on the Irregularities of the Teeth and Their Corrections (Fig. 2-6).12 In that text, he also demonstrates detailed orthodontic appliances, and he was among the first to suggest the advantages of mild (rather than heavy) force applied at intervals to effectively move the teeth.10 It was common practice through the later half of the 19th century to extract the teeth in response to most dental problems.9,60 Restorative dentistry was generally not the first choice for the management of “toothaches.” Most adults at that time (i.e., the 1880s) did not have a full complement of teeth nor was there much stigmata associated with partial edentulism.210 Details of how the teeth occluded with each other seemed important only when establishing how upper and lower dentures were to meet so as to prevent loosening or mobility when wearing them and to improve chewing ability. It was a natural extension of this thinking for a prosthodontic-trained dentist like Edward H. Angle to develop a more holistic concept regarding the importance of the occlusion of the natural dentition (Fig. 2-7).5–8 During his career, Angle taught prosthetics at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minn), Northwestern University Dental School (Chicago, Ill), and the Missouri Dental College (St. Louis, Mo). Dr. Angle’s interest in dental occlusion and his ingenuity and dedication with regard to the correction of malocclusion led to the development of the specialty that we now call “orthodontics.” Angle’s textbook, Treatment of Malocclusion of the Teeth, was first published in 1887 (Fig. 2-8).6 It went into seven much-revised editions, and it laid the foundation for the modern specialty of orthodontics. The publication of Angle’s classification of malocclusion during the 1890s was a key step in the development of orthodontics (Fig. 2-9).42,43 Angle introduced the first precise and simple definition of the normal human occlusion of the natural dentition. He postulated that a key aspect of how the teeth should fit together was the positioning of the maxillary first molars. He then went on to describe three classes of malocclusion that were based on the occlusal relationships of the first molars: Figure 2-8 Dr. Angle published a comprehensive text entitled A Treatment of Malocclusion of the Teeth and Fractures of the Maxillae, the first edition of which was published in 1887. It went into seven revised editions, and it laid the foundation for the modern specialty of orthodontics. Figure 2-9 Angle described three classes of malocclusion based on the relationships of the first molars: Class I, Class II, and Class III. Class I: There is a normal relationship of the molars, but the line of occlusion is incorrect as a result of malposed teeth, rotations, or other causes. Class II: The lower molar is distally positioned relative to the upper molar, and the line of occlusion is not specified. Class III: The lower molar is mesially positioned relative to the upper molar, and the line of occlusion is not specified. Angle’s classification actually has four classes: By the early 1900s, orthodontists no longer just aligned irregular teeth in each arch.175,218 The practice had now evolved into the treatment of malocclusion (i.e., how the upper and lower teeth align with each other). Angle’s philosophy was to achieve a specific relationship between the upper and lower teeth for each patient. Since Angle’s precisely defined dental relationships also required a full complement of teeth in each arch, the maintenance of an intact dentition became an important component of orthodontic treatment. Angle and his followers strongly opposed extraction for orthodontic purposes.69 In an attempt to achieve the three-axis control of tooth movement, Angle introduced the ribbon arch (Fig. 2-10).70 He then devised the edgewise appliance to overcome the weaknesses of the ribbon arch (Fig. 2-11). The Angle reoriented bracket slot was designed to control the bodily movement of teeth and to limit tipping.135 Angle also heavily relied on the use of intraoral rubber bands and limited the use of extraoral appliances (e.g., headgear) as much as possible. Figure 2-10 The ribbon arch appliance, which was introduced by Angle in 1916. The vertical slot in the bracket accepts either round or rectangular wire, which in turn is held in place by a locked pin. Figure 2-11 The edgewise bracket attachment comes in a variety of modifications. The original single bracket (left) has been widened for molar teeth and for greater rotational control (center). The twin edgewise modification (right) is available in different widths, and it is used most frequently because of its greater versatility, its reduced frictional component, and its adaptability to various light-wire techniques. Angle was among the first to state that jaw discrepancies exist in some individuals and that these discrepancies will prevent the achievement of a normal occlusion. He then acknowledged the need for jaw-straightening surgery. In Chapter 14: Operative Surgery of the sixth edition of Angle’s textbook, he states that the use of appliances to move teeth may be properly called conservative surgery to distinguish it from more bold or aggressive operations involving the use of cutting instruments, which were designated as operative surgery. He states the following: “While such operations [mandibular osteotomies] should probably be employed only as auxiliary to the conservative method, they are doubtless destined to play an more important part in the practice in the future.”6 Dr. Angle worried that no technique that relied solely on tooth movement could establish the appropriate relationships of the teeth or truly improve the facial lines in cases involving the severe overdevelopment of the inferior maxilla [mandible].6 He felt that these cases may be successfully treated by removing a section of bone from each of the lateral halves of the mandible. At the time, the removal of a single complete section of the jaw had been reported for cases involving such conditions as ankylosis, tumors, and gunshot wounds, but Dr. Angle was unable to find information about the removal of complete sections from each of the lateral halves of the mandible. This idea was discussed by Dr. Angle with various surgeons and dentists and determined to be feasible. His proposal involved the following6: • Careful photographs should first be taken of the patient. • Two accurate models should be made of the lower dental arch, and one should be made of the upper. • One of the plaster models of the lower jaw should then be sawed through and the sections removed. • The positions and extent of the sections should be carefully experimented with until the three remaining sections of the model could be made to best harmonize with the upper arch so that the teeth may be in best possible occlusion with those of the upper jaw. • The sections of the plaster model should then be cemented or waxed together. • Over this reconstructed model, a vulcanite or metal splint should then be formed. • With the use of careful comparisons and measurements of the reconstructed model as compared with the unchanged model, the exact size and form of both resections of bone to be removed can be determined so that there need be no guessing as to the relationships of the bone. In this way, complete apposition of the cut ends can be made. • Because there is a lingual inclination of the lower incisors in all cases of mandibular prognathism, the sections of bone to be removed must not be parallel on their sides but instead more or less wedged or V-shaped to gain the best positions for the occlusion of the incisors as well as for the appearance of the chin. • The degree of variation from the parallel of the lines of bone resection must be determined by the conditions that are present (i.e., patient variation). • Because the operation must be skillfully performed, the most rigid support should be given to the reconstructed jaw. This technique (i.e., a cap splint over the teeth) should give more rigid support than is possible with the crude, unstable, and unmechanical plan of wiring the ends of the bone together, which is so often employed for the reduction of fractures. According to Dr. Angle, “The question most often raised by dentists in discussing the practicability of an operation as outlined above was the uncertainty as to union of the bones and as to impairment of vitality of the teeth in the anterior segment [of the mandible].”36 However, Dr. Angle helped with the overcoming of these concerns via two case reports that were presented in his textbook, Treatment of Malocclusion of the Teeth and Fractures of the Mandible: Angle’s System6 (pp 173-184): The introduction of the cephalometer by Holly Broadbent in 1931 was another important milestone that placed orthodontic research on a scientific foundation (Fig. 2-12).157 For the first time, it made possible the accurate study of the facial bones in the growing child (Figures 2-13 and 2-14). It became a valuable supplement to the orthodontist’s plaster models and intraoral x-rays. The value of serial cephalograms in clinical practice was quickly realized. Broadbent’s original work on the “face of the normal child” and Brody’s classic research “on the growth pattern of the human head from the third month to the eighth year of life” were among the earliest contributions.163 These were followed by the research of Down’s “Variations in Facial Relationships,” the work of Thompson in “Functional Analysis of Occlusion,” Wylie’s “Assessment of Anterior-Posterior Dysplasia,” and the work of Margolis’ “Basic Facial Pattern and Its Application in Clinical Orthodontics.”174 The use of cephalometric radiography in clinical practice became widespread after World War II and made clear to all clinicians that many of the Class II and Class III malocclusions being treated actually resulted from abnormal skeletal relationships rather than just malposed teeth.165 These radiographic truths were hard to ignore and further inspired orthodontists and surgeons to search for operative solutions.181 Figure 2-12 Photograph of Holly Broadbent (1894-1977). From Broadbent BH Sr., Broadbent BH Jr and Golden WH: Bolton Standards of Dentofacial Developmental Growth, St. Louis, C.V. Mosby, 1975. Figure 2-13 Broadbent was the first to develop the standardized lateral “head plate.” The cephalometer is a device for holding the patient’s head, the x-ray film, and the central ray of the x-ray machine in proper relationship with one another. Ear-rod extensions are necessary to adjust the head so that the profile is centered, regardless of the size or shape of the head. The orbital pointer and the ear rods adjust the patient’s head along the horizontal or Frankfort plane. An adjustable chair is used, and the teeth are placed in “centric occlusion” unless otherwise indicated. The cephalometer may be rotated so that posterior and anterior radiographs as well as profile radiographs can be taken. The central ray is directed through the ear rods, thereby producing a circle on the x-ray film. From Broadbent BH Sr., Broadbent BH Jr and Golden WH: Bolton Standards of Dentofacial Developmental Growth, St. Louis, C.V. Mosby, 1975. Figure 2-14 The cephalostat device, as described in Figure 2-13, is shown with a patient who is positioned and ready for film exposure. From Broadbent BH Sr., Broadbent BH Jr and Golden WH: Bolton Standards of Dentofacial Developmental Growth, St. Louis, C.V. Mosby, 1975. Another “orthodontic truth” was also soon to fall. A purest “Angle” approach to maintaining and straightening all of the teeth in all patients frequently proved untenable with regard to the maintenance of the occlusion after the appliances were removed.54,144,145 This non-extraction, arch-expansion approach gave little consideration to long-term periodontal health or to the individual’s overall facial aesthetics.161 The extraction of teeth (typically the bicuspids) to achieve occlusal stability and periodontal health was reintroduced into American orthodontics during the 1930s by Charles Tweed (Fig. 2-15) and simultaneously into the United Kingdom (Australia) by Raymond Begg (Fig. 2-16) (see Chapter 17 for in-depth discussion).47–49,59,204 Dr. Lawrence F. Andrews’ pioneer contributions to the field of orthodontics and the treatment of dentofacial deformity must also be mentioned (Fig. 2-17).2–4 After completing orthodontics training at Ohio State University in 1958, he entered private practice that was limited to orthodontics. Early in his career, Dr. Andrews recognized clinical problems that were yet unsolved and sought solutions. This sent him on a search to better understand occlusion as well as deviations from normal. Between 1960 and 1964, Dr. Andrews began to gather data for analysis. One hundred and twenty non-orthodontic normal (dental) models were acquired with the cooperation of local dentists, orthodontists, and a major university. The models selected for study were of teeth that had never undergone orthodontic treatment; that were straight and pleasing in appearance; that had a bite that looked generally correct; and that, in Dr. Andrews’ judgment, would not benefit from orthodontic treatment. Dr. Andrews studied the crowns of this multisource collection of models to ascertain which characteristics, if any, would be found consistently in all of them. Angle’s molar cusp groove concept was validated but found to be incomplete. After meticulous evaluation, including comparison with “treated cases” from the nation’s most skilled orthodontists (n = 1150), six consistent occlusal characteristics were formulated by Dr. Andrews in general terms and then explained in detail.2 The six fundamental qualities or Six Keys of Optimal Occlusion were validated not solely because all were present in each of the non-orthodontic normal models (n = 120) but because the lack of even one of the six was a defect that was predictive of an incomplete end result in the orthodontically treated models that were studied (n = 1150). In his published article, Dr. Andrews acknowledged that, although each normal person is unique in his or her own way, they nevertheless have much in common.2 The 120 non-orthodontic normal models studied differed with regard to certain aspects, but all shared the Six Keys. Dr. Andrews suggested that we use as our benchmark “nature’s best” and that, in the absence of abnormalities outside of our control, we limit compromise and strive for the ideal. He developed the straight-wire appliance in 1970 for orthodontic use to help accomplish these objectives. This preadjusted appliance soon became the standard of the specialty.2–4 Element I: Proper arch shape and positioning of the maxillary and mandibular teeth (roots) over the basal bone Element II: Proper horizontal (sagittal) projection of the maxilla Element III: Proper width of the maxillary and mandibular arches Element IV: Proper vertical height of the maxilla Element V: Proper prominence (shape) of the chin (i.e., pogonion prominence) Element VI: Establishment of the Six Keys to Optimal Occlusion By the mid 1970s, Dr. Proffit recognized the benefits of a collaborative surgeon–orthodontist interaction for the correction of dentofacial deformities.164 He and others convincingly demonstrated to surgeons that rectangular orthodontic arch wires in edgewise brackets were satisfactory for surgical patients without the need for the intraoperative placement of Erich arch bars. This paved the way for the routine preoperative orthodontic relief of dental compensations, and it was followed by the placement of orthodontic “surgical wires and hooks” for intraoperative use. After the initial surgical healing, a smooth transition to orthodontic maintenance and detailing soon became the standard of care. Dr. Proffit was also an early believer in the importance of a collaborative effort to understand the patient’s presenting dysfunction and dysmorphology and then to develop a comprehensive treatment plan. The use of a cephalometric analysis with prediction tracings followed by dental model planning with splint construction became the routine. Dr. Proffit and others also insisted on analysis of the early results that were achieved. This was followed by critical studies of the long-term outcomes after various surgical approaches and orthodontic techniques were employed. This analytic approach has been responsible for much progress in the field over the past four decades. According to Dr. William R. Proffit* (Fig. 2-18), orthodontics in the 21st century differs from that of the previous century in three fundamental ways162,163: 1. There is more emphasis on both facial and dental aesthetics and less on the details of dental occlusion as an overriding objective. This has much to do with the safe and reliable orthognathic surgical techniques that are currently available and with the recognition that long-term stable occlusion and periodontal health can best be achieved in conjunction with harmonious jaw relationships. This will require extractions when necessary to uncrowd and achieve periodontal health; decompensating orthodontic therapy to place teeth that are solidly in the alveolar bone; and jaw-straightening surgery, when indicated. 2. Patients and families expect greater involvement in the treatment planning process. Full disclosure requires the orthodontist to consider and review ideal and compromised treatment options. Providing a balanced and objective assessment of each option’s effect on facial aesthetics, dental stability, periodontal health, speech articulation, and the upper airway is ideal. Consultation with appropriate dental, surgical, and medical specialists before instituting treatment has become the standard of care. 3. Orthodontics is now offered not just to children, adolescents, and young adults but also to older adults through an interdisciplinary approach. Consideration should be given to facial aesthetics, occlusion, periodontal health, the upper airway, speech articulation, and the long-term maintenance of the dentition. There is increased emphasis on coordinated treatment with other dentists, surgeons, and medical specialists. Taking advantage of currently available sophisticated orthodontics and orthognathic surgery to provide individuals of all ages with quality care should now be considered routine. Simon Hullihen described a procedure for the correction of mandibular dentoalveolar protrusion in the American Journal of Dental Science in January 1849 (Fig. 2-19, A).18,98 Technically, this was a bilateral bicuspid region wedge ostectomy to “set back” the anterior mandibular dentoalveolar segment. The osteotomy did not violate the inferior border of the mandible. The procedure was performed on a middle-aged woman whose mandibular deformity was the result of a severe burn scar contracture of the anterior neck and lip from an injury that had occurred during her childhood (see Fig. 2-19, B and C). Figure 2-19 A, Photograph of Simon Hullihen (1810-1897). B, Illustration of anterior mandibular dento-alveolar segmental osteotomy proposed and C, carried out by Dr. Hullihen. A from Ambrecht EC: Hullihen, the oral surgeon. Int J Orthod Oral Surg 23:377, 511, 598, 711, 1937. B and C from Hullihen S: Case of elongation of the under jaw and distortion of the face and neck, caused by a burn, successfully treated. Am J Dent Sci 9:157, 1849. In 1887, Berger from Lyon, France, described bilateral condylar neck osteotomies to set back the prognathic mandible.90 In 1895, Jaboulay also reported the bilateral osteotomy of the condylar neck (condylectomy) for the correction of prognathism.100 This method continued to be popular in France for the treatment of prognathism through the 1950s.75 On December 19, 1897, Vilray Blair in St. Louis, Mo, carried out a distinct modification of the original Hullihen procedure for the treatment of mandibular prognathism (see the “Second Patient (Operation)” case report by Dr. Angle earlier in this chapter) (Fig. 2-20).38 The operation was performed on a 22-year-old man with asymmetric mandibular prognathism. The young man had difficulty with chewing and speech articulation, and he also was self-conscious about his appearance; thus, he was enthusiastic about proceeding with the recommended surgical plan. Dr. Blair stated that the immediate surgical objective was to carry out bilateral body osteotomies to shorten the horizontal ramus [body of the mandible] and to change the mandibular angle [rotate the distal mandible counterclockwise], thereby allowing for the closure of the open bite. Dr. Blair’s preoperative concerns about the operation included the following: 1. Could a portion of the mandible be cut out on each side in a satisfactory way? 2. Would sacrifice of the inferior dental nerve cause detrimental injury to the distal mandible? 3. After healing had occurred, would the mandible continue to grow and cause a recurrence of the deformity? Through cadaver dissections, Dr. Blair satisfied his concerns regarding whether the mandible could be sectioned and repositioned successfully. As a result of the age of the patient (22 years), he had little concern regarding further growth after surgery. He conferred with two other surgeons (Dr. E.H. Gregory and Dr. P. Tupper), both of whom concurred that the surgical plan seemed reasonable. The patient was also under the care of Dr. J.W. Whipple (orthodontist). Dr. Blair had discussed the feasibility of a surgical solution for mandibular prognathism with Dr. Angle (the patient had also consulted with Dr. Angle before surgery), and Dr. Angle “had advised such an operation.”38 The surgery was carried out at the Missouri Baptist Sanatorium. The surgery commenced with the patient under chloroform anesthesia at 9:20 AM with the patient in the recovery room by 10:30 am. During the operation, the patient’s head was hyperextended over the end of the operating room table. Skin incisions below the inferior border of the mandible on each side provided exposure. The incisions extended up into the mouth and involved cutting through the mucous membrane. A full-thickness osteotomy was to be completed on the left side of the mandible between the first and second bicuspids and on the right side between the second bicuspid and the first molar. The osteotomy was initiated with a “double-bladed saw” three quarters of the way through on each side; the inferior border remained intact.38 This allowed for the presence of a stable mandible on each side before the cut was fully completed on either side. A drill was used to place holes on either side of the osteotomy site for eventual “cooper wire fixation”38 near the inferior border on each side before cutting through the inferior border on either side. After the completion of both full-thickness osteotomies, soft gutta-percha was placed over the mandibular dentition, and the upper and lower teeth were firmly wired together through the gutta-percha. This method of intermaxillary fixation immobilized the distal mandible in its new position for the closure of the open bite. Dr. Blair stated that “this method of fixation was suggested to him by seeing Dr. Angle’s fracture bands.”38 The fracture band method of mandible fracture management was commonly in use. Dr. Blair stated that, as the patient was emerging from the anesthesia, the vomiting of mucus and blood occurred, thereby necessitating the cutting of the intermaxillary fixation.38 After the vomiting subsided, rather than reapplying intermaxillary fixation, a Barton bandage of plaster was used to secure the mandible into occlusion with the maxilla.21 When the Barton bandage was removed several weeks later, Dr. Blair felt that there was “bony union on the right side and a very slight but perceptible motion on the left side when the fragments were grasped.”38 Dr. Blair decided to take the patient to the office of the treating dentist (orthodontist), Dr. Whipple. He requested that Dr. Whipple place two dental bands with a bar between them across the weak left osteotomy site. This would afford the patient sufficient support and allow him to go without the additional protection of a Barton bandage or intermaxillary fixation.” Unfortunately, while he was tightening the bands across the left and right osteotomy sites, Dr. Whipple “broke the union of the provisional callus.”38 At this point, Dr. Whipple applied properly adjusted bands to the teeth on the left side of the mandible, and Dr. Blair reapplied a Barton plaster external facial bandage.38 Dr. Whipple also placed crowns on the mandibular teeth posterior to the osteotomy sites so that the molars would occlude properly with the upper teeth, and he filled some points on the teeth to improve the occlusion of the incisors.38 Apparently, the combination of the mandibular setback with the clockwise rotation resulted in “a small [osteotomy] gap between the second bicuspid and first molar on the right side” but “without a gap [previous edentulous space] in the left first bicuspid region.”38 Despite these difficulties, the osteotomies went on to heal with a reasonable correction of the occlusion.38 Dr. Blair stated that there was “almost a complete loss of cutaneous sensation of the lower lip” but that the “sensation of the tooth-pulp is good.”38 Interestingly, Dr. Whipple, the treating dentist and orthodontist, published his version of the patient’s surgery, convalescence, and ultimate result in Dental Cosmos in 1897.212 This was before the journal publication by Dr. Blair, in which he gave a full account of the case from his perspective.38 Although Dr. Whipple’s description of events varied somewhat from what was eventually reported by Dr. Blair, both concurred that the procedure had taken place and that it was a success. In his textbook, Dr. Blair cautions the surgeon that “the lower jaw should be set back only far enough to be in harmony with the rest of the face” and that the surgeon should “leave it to the orthodontist to bring forward the upper incisors if necessary.”40 He stated that “an orthodontist should be involved in the planning of the patient’s treatment from the beginning.”40 For some patients, Dr. Blair notes that “it would be of considerable advantage to have the upper jaw [orthodontically] expanded and the upper incisors and canines brought forward before the lower jaw is surgically set back.”40 A horizontal osteotomy through the ascending ramus, on each side and above the occlusal plane, as a method of “setting back” the prognathic mandible was first described by Lane.117 During the early 1900s, Blair39 and Babcock19 also made use of the horizontal ramus osteotomy on each side for the correction of prognathism.36 In 1912, Harsha reported bilateral wedge resections of the mandible body near the angle regions to set the mandible back; this was similar to the procedure that Blair described in 1897.89 Unfortunately, at least one of his reported patients suffered the loss of (and the eventual need to remove) the entire anterior part of the jaw. In 1945, Moose143 may have been the first to describe a fully intraoral technique to carry out horizontal ramus osteotomies for the correction of mandibular prognathism. In 1950, G.V. Barrow and Reed O. Dingman discussed the surgical management of mandibular prognathism.22 They described a method to determine the exact amount and shape of mandibular bone to be resected on each side by using dental models that involved the construction of splints and templates. Their described meticulous approach was similar to that of Angle in the 1903 edition of his textbook.7 The operation was reported by Dingman as having a two-stage approach71,72; this was to separate the intraoral and extraoral aspects to maintain control of the segments and to limit the risk of infection. During the first stage, the teeth to be extracted (i.e., the first molars) were removed with the use of local anesthesia. As determined by the “preconstructed template,” osteotomies for wedge resection were initiated through the intraoral approach at the time of the extractions. Approximately 4 weeks later, the patient was anesthetized in the operating room for the second stage. An incision of the skin of the neck was made 2 cm below the inferior border, and the lower aspect of the mandible was exposed on each side. The previous intraoral vertical cuts on each side were identified. With a power-driven bur or saw, the two vertical cuts were continued through the inferior border. Attempts to preserve the inferior alveolar nerve were made. Stabilization across the osteotomy on each side site was with 24-gauge stainless-steel wires. The teeth were placed into occlusion with the use of either orthodontic appliances or Erich arch bars. In either case, to improve accuracy, the mandibular dentition was secured into a prefabricated acrylic wafer before intermaxillary fixation occurred. In 1954, J.B. Caldwell and G.S. Letterman devised a vertical osteotomy of the ascending ramus that involved the decortication and perforation of the fragments and then the splitting of the medial and lateral cortices of the ramus to allow for setback of the mandible followed by direct wire fixation.45,46 This innovative technique had the advantage of providing at least a degree of overlapping of the bone for more reliable and rapid healing. All of these techniques for the management of mandibular prognathism79,87,91–93,96,138,167,211 eventually fell by the wayside after the introduction by Hugo Obwegeser of what we now refer to as the “intraoral sagittal splitting of the mandibular ramus,” which is described later in this chapter.149 The stabilization of the osteotomy segments is now generally accomplished with titanium bicortical screws or with a titanium plate and screws in accordance with the pioneering innovations of H. Luhr, who is also discussed in a later section of this chapter.127 An important early maxillofacial textbook publication was Surgery and Diseases of the Mouth and Jaws by Vilray P. Blair (Fig. 2-21).40 At the time of publication, Dr. Blair was a Major in charge of the subsection of Plastic and Oral Surgery, Section of Surgery of the Head Office of the Surgeon General of the Army in Washington, DC.197 He was also a professor of oral surgery at the Washington University Dental School and an associate in surgery at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo. In his textbook, Chapter 21 deals with the treatment of deformities and malrelations of the jaws. Figure 2-21 Vilray P. Blair published a text entitled Surgery and Diseases of the Mouth and Jaws, the first edition of which was published by the C.V. Mosby Company in 1912. • To not undertake any cases without first having the fullest confidence in his or her patient • To remember that procedures undertaken for only “moderate” deformity should not be taken lightly • To remember that maximum restoration will also require orthodontics • To remember that the earlier a competent and genial orthodontist is associated with the case, the better it will be for both the surgeon and the patient According to Dr. Blair, for the treatment of mandibular micrognathia, a surgical procedure may be used to “bring forward the lower jaw to harmonious outline” with the maxilla.40 Malocclusion in a patient with a jaw deformity results from the “pressure and counter pressure of growth and apposition.”40 Normal occlusion cannot be established by jaw surgery alone. To reach certain objectives, the surgeon “shall have knowledge of occlusion and of the scope and limitations of orthodontic procedures.”40 Blair went on to say this: “We have to accept the upper jaw position but the lower jaw is capable of almost any kind of surgical adjustment. The complication of an ununited fracture of the lower jaw is rare. The complication of necrosis or loss of teeth from surgically sectioning the ramus is not reported in the world literature.”40 However, “osteotomy of the ramus of the mandible is a recognized procedure for the treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis.”40 Esmarck, who was a prominent surgeon when Dr. Blair was discussing this treatment, recommended the removal of a whole section of the horizontal ramus to avoid a union (i.e., reankylosis) when creating a pseudoarthrosis for the treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. However, Blair felt that surgeons did not need to concern themselves with the possibility of necrosis or nonunion when “completing an osteotomy through the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle.”40 Blair felt that the surgeon could correct mandibular retrognathia by completing a ramus osteotomy on each side and then “bringing the distal mandible forward to meet a good occlusion with the maxillary arch.”40 Intermaxillary fixation could then be achieved with stainless steel wires and the use of soft cement in between the occluding teeth.40 Fixation across the osteotomy site was felt to be unnecessary. The (horizontal) ramus osteotomy was made at or just above the mandibular occlusal plane with the use of a Gigli saw placed transcutaneously.39 The osteotomy was cut through the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle, which was not felt to be important either to the circulation of the mandible or as a cause of disability. The ramus osteotomies were later made blindly and transorally with a Gigli saw.40 According to Dr. Blair, “the operation presented three distinct problems: (1) the cutting of the bone [which is the easiest of the three]; (2) the placing of the jaw into its new position; and (3) holding it there [for the time required for healing].”40 He used postoperative x-rays to show that the fragments of the ramus remained in contact at the posterior border of the osteotomy. “[A]s the distal mandible is brought forward,” said Dr. Blair, “a gap is created anteriorly while the fragments remain in contact at the posterior border. For healing to occur, the bone gap must be filled with granulations. The resulting bone scar tends to contract [relapse] for months afterwards.”40 The maintenance of tight intermaxillary fixation was felt to be essential to maintain the new position. Blair used iron wire for its strength, lack of stretch, and pliability; it could also be twisted, unless it was damaged by sharp instruments.40 He also used quick-setting cement between the occlusal surfaces of the molars to prevent the placement of postoperative forces on the anterior teeth, which could cause the patient significant pain.40 Dr. Blair also used this same operation involving horizontal ramus osteotomies for the treatment of ankylosis associated with severe mandibular retrusion; this operation was first carried out by Dr. Mudd with Dr. Angle assisting in 1897. Dr. Blair also suggests addressing the residual chin deformity by either “injecting paraffin into the chin or by inserting a piece of cartilage or rib.”40 Most of the early reported attempts at horizontally advancing the retrognathic mandible focused on the mandibular body. Dr. Blair specifically addressed the problem of an anterior open bite by rotating the distal mandible counterclockwise after body osteotomies and ostectomies. He states that the “sectioning of the mandible on both sides in front of the first molars [as long as the molars are in occlusion] is the preferred procedure. The anterior mandible can then be moved into good occlusion with the upper teeth. In other cases, it is necessary to remove a V-shaped section of the bone on each side with extraction of the tooth [bicuspid]. The apex of the V-shaped ostectomy segment is at the lower border of the mandible and usually a tooth is extracted from the site of the section on each side. The bone is cut using a Gigli saw or a cross-cut Fisher bur.”40 Dr. Blair goes on to state that “the deformity is in both jaws but the operation is limited to the lower jaw. It is best to restore the lower jaw to its proper form and then manage the residual open bite by bringing down the upper incisors with orthodontic appliances or by extending the upper teeth with porcelain crowns. Fixation is achieved with a prefabricated splint constructed on plaster dental models. This will prevent pulling down of the distal segment by the digastric and geniohyoid muscles.”40 A variety of techniques were carried out by pioneering surgeons to address concerns regarding the maintenance of contact between the fragments to achieve bony union; soft-tissue coverage to limit infection; opposing muscle pull to limit relapse; and adequate fixation. In 1928, a “step osteotomy” of the body of the mandible was proposed by Von Eiselberg.201 Also in 1928, Gadd reported a stepped procedure for the body of the mandible for the purpose of correcting asymmetric mandibular deficiency.80 That same year, Limberg completed L-shaped sliding osteotomies of the mandibular body to improve bone-to-bone contact after advancement.122,123 In 1931, Kostecka published his work with the Blair-type transcutaneous horizontal ramus osteotomies with the use of a Gigli saw (Fig. 2-22).115 In 1936, Kazanjian performed mandibular “step” osteotomies anterior to the mental foramen with extension back into the body of the mandible to allow for advancement and fragment approximation (Fig. 2-23, A through D).68,103–108 The constant problems encountered with all of these approaches involved maintaining sufficient bone-to-bone contact and achieving adequate fixation for a stable long-term result. The problems were finally solved through the pioneering work of Hugo Obwegeser (i.e., the intra-oral sagittal splitting of the ramus of the mandible) and Hans Luhr (i.e., plate and screw fixation across the osteotomy site), which is described later in this chapter. In 1960, Caldwell described vertical osteotomies of the ramus with interpositional iliac bone graft for the correction of micrognathia.45 A C-osteotomy of the ramus was later described by Caldwell and colleagues, in 1968.46 Although these osteotomies with interpositional grafting are occasionally used for the management of mandibular retrognathism, the Obwegeser sagittal split ramus osteotomy is generally preferred. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, many surgeons saw the need to mobilize the maxilla for better access either to remove an epipharyngeal tumor or for the correction of maxillary deformity. Figure 2-22 As originally depicted, methods for the correction of mandibular deformities by the blind technique. A, The method of Blair. From Blair VP: Surgery and diseases of the mouth and jaws, ed 3, St. Louis, 1914, C.V. Mosby Company. B, The method of Kostecka. From Kostecka F: Die chirurgische therapie der proggeni. Zahnaertzliche Rundschau 40:669–687, 1931. Figure 2-23 A, Dr. Varaztad H. Kazanjian leaving Buckingham Palace after his investiture as a Companion of St. Michael and St. George for his services during World War I, March 15, 1919, B, View of the hospital showing Dr. Kazanjian’s three wards, circa 1916, C, Photograph of the hospital ward within the makeshift (Harvard unit) barrack where trauma patients were under the care of Varaztad H. Kazanjian (1915-1919). D, Photograph of Varaztad H. Kazanjian later in his career. A and B, From The Harvard Medical Library in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine. C, From Deranian HM: The miracle man of the western front. Bull Hist Dent 32:85-95, 1984. In 1868, David Williams Cheever of Boston published a report of a Le Fort I osteotomy for the purpose of exposing and removing a large nasopharyngeal polyp (Fig. 2-24).55,88 After completing the tumor resection, the maxilla was placed back in its original location. Cheever stated, “so far as I know, the operation including both superior maxillary bones—is novel.”55 “Nothing but the posterior attachments of the upper maxilla now prevented their depression and hinging on the pterygoid processes. The upper jaw was brought down so as to expose the tumor.”55 By the early 1900s, reports of series of patients undergoing maxillary osteotomies for the purpose of tumor resection were detailed in the literature.37 Figure 2-24 Photograph of David Williams Cheever of Boston (1831-1915). Courtesy Harvard University Portrait Collection. With reference to the treatment of dentofacial deformities, in 1921 in Berlin, Cohn-Stock was the first to report an elective maxillary osteotomy to establish a preferred occlusion.56,214 He used a two-stage approach (a precaution against flap necrosis) when completing an anterior maxillary osteotomy. Martin Wassmund, the founder of the “German school” of maxillofacial surgery, is credited with developing the one-stage anterior maxillary osteotomy.205–207 The Wassmund procedure was completed through limited palatal and labial incisions with subperiosteal tunneling. The tunneling incisions limited mobilization, but this was thought to be necessary to maintain circulation. Karl Schuchardt is credited with developing the posterior maxillary segmental osteotomy.171–173 This was completed with the use of broadly elevated full-thickness palatal flaps and limited labial flaps. In 1959, Köle described the combined simultaneous maxillary and mandibular anterior segmental (alveolar) osteotomies for the correction of bimaxillary protrusion and other forms of open bite, deep bite, and posterior crossbite.111–114

Pioneers and Milestones in the Field of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

Pioneers in the Field of Orthodontics

Background

Edward H. Angle

Holly Broadbent

Charles Tweed and Raymond Begg

Lawrence F. Andrews

William R. Proffit

Early Pioneers in the Field of Orthognathic Surgery

Mandibular Setback for Prognathism

Mandibular Advancement for Retrognathism

Maxillary Osteotomies for Management of Dentofacial Deformity

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pioneers and Milestones in the Field of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery