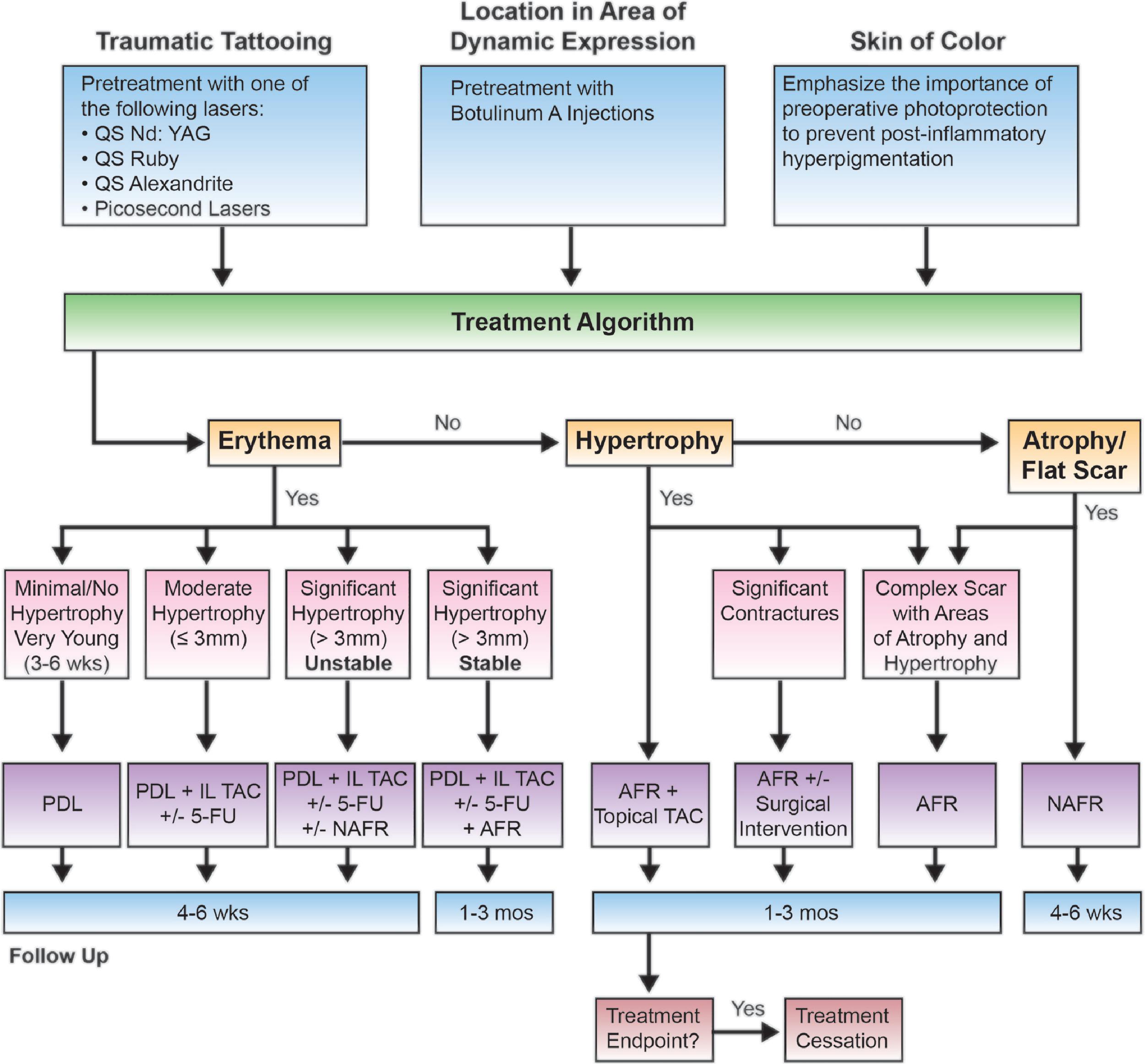

Background and Treatment Algorithm

This chapter combines information and treatment pearls presented throughout this book to provide a practical framework for approaching the management of scars based on specific scar features. Although each section will provide treatment recommendations for managing an isolated scar feature, it is important to remember that scars are inherently heterogeneous and often contain multiple features. For example, burn scars are often complex with features of erythema, hypertrophy, atrophy, dyspigmentation, and contracture. The best clinical outcomes occur with combining treatments in an approach that holistically treats the multifaceted features of the scar.

This treatment algorithm ( Fig. 11.1 ) has been adapted from Kauvar et al.’s excellent paper to help guide the laser surgeon in their approach to the management of scars.

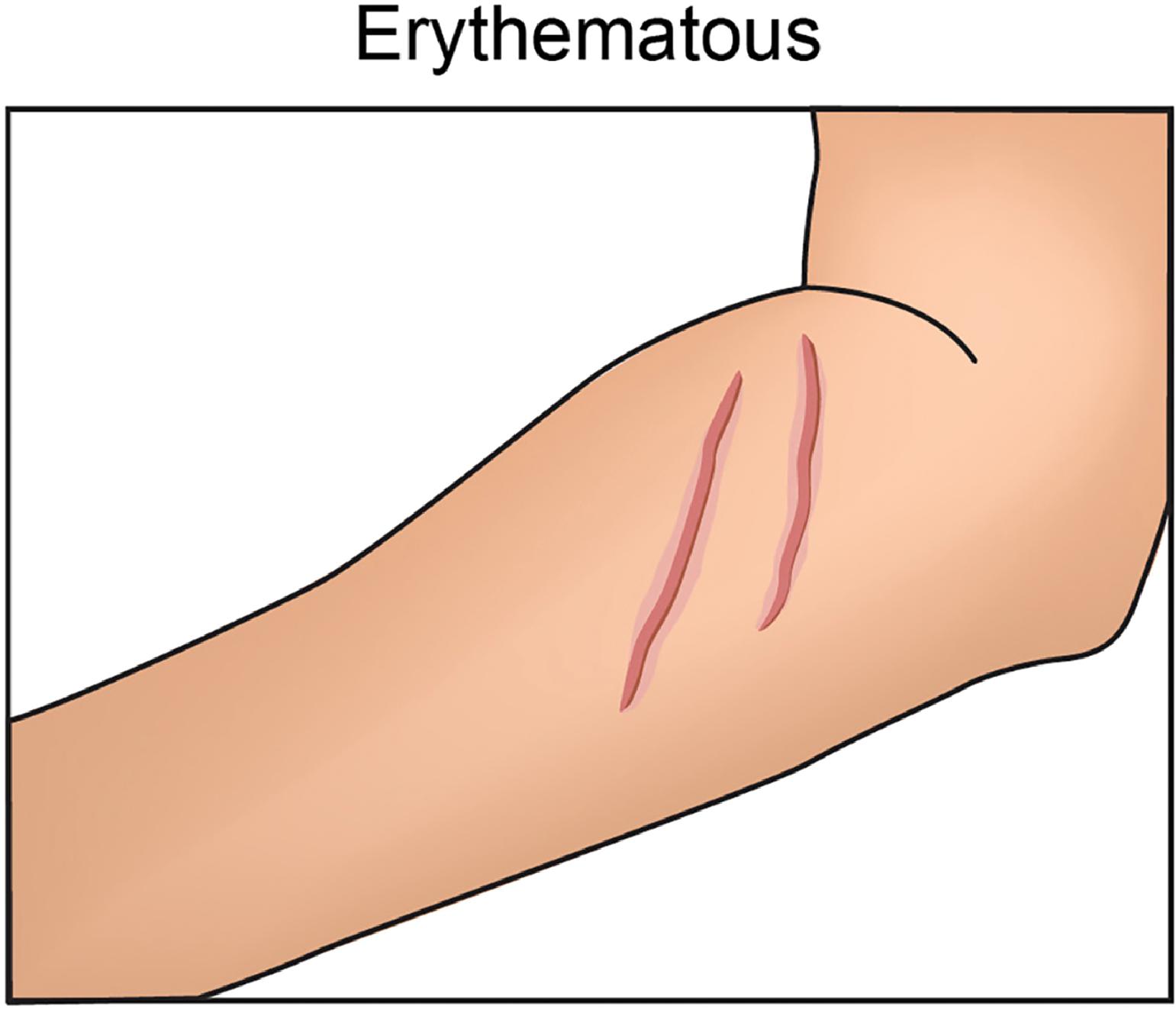

The Erythematous Scar

- •

Prolonged erythema ( Fig. 11.2 ) is often the first manifestation of scar formation and can be treated early to improve symptoms and impede scar spread and hypertrophy.

Fig. 11.2

The Erythematous Scar.

Medical illustration courtesy of Sheila Macomber, medical illustrator.

- •

Vascular lasers and light are used, most often the pulsed dye laser (PDL, 595 nm) or the potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP, 532 nm) and lithium triborate (LBO) lasers and, less frequently, intense pulsed light (500–1300 nm).

- •

The target chromophore is oxyhemoglobin within vessels created during the neovascularization process of wound healing.

- •

The clinical endpoint may be as subtle as erythema, as vessels are not often visible in red scars. Transient vessel disappearance or vessel darkening may be seen. Mild bruising, erythema, and edema may occur, although the endpoint of bruising is not necessary for treatment benefit. Tissue graying, immediate purpura, or splatter is an unwanted endpoint, and settings should be reevaluated.

- •

Treatments can be performed as soon as reepithelialization has occurred and repeated monthly, with improvement typically seen after two to four treatments.

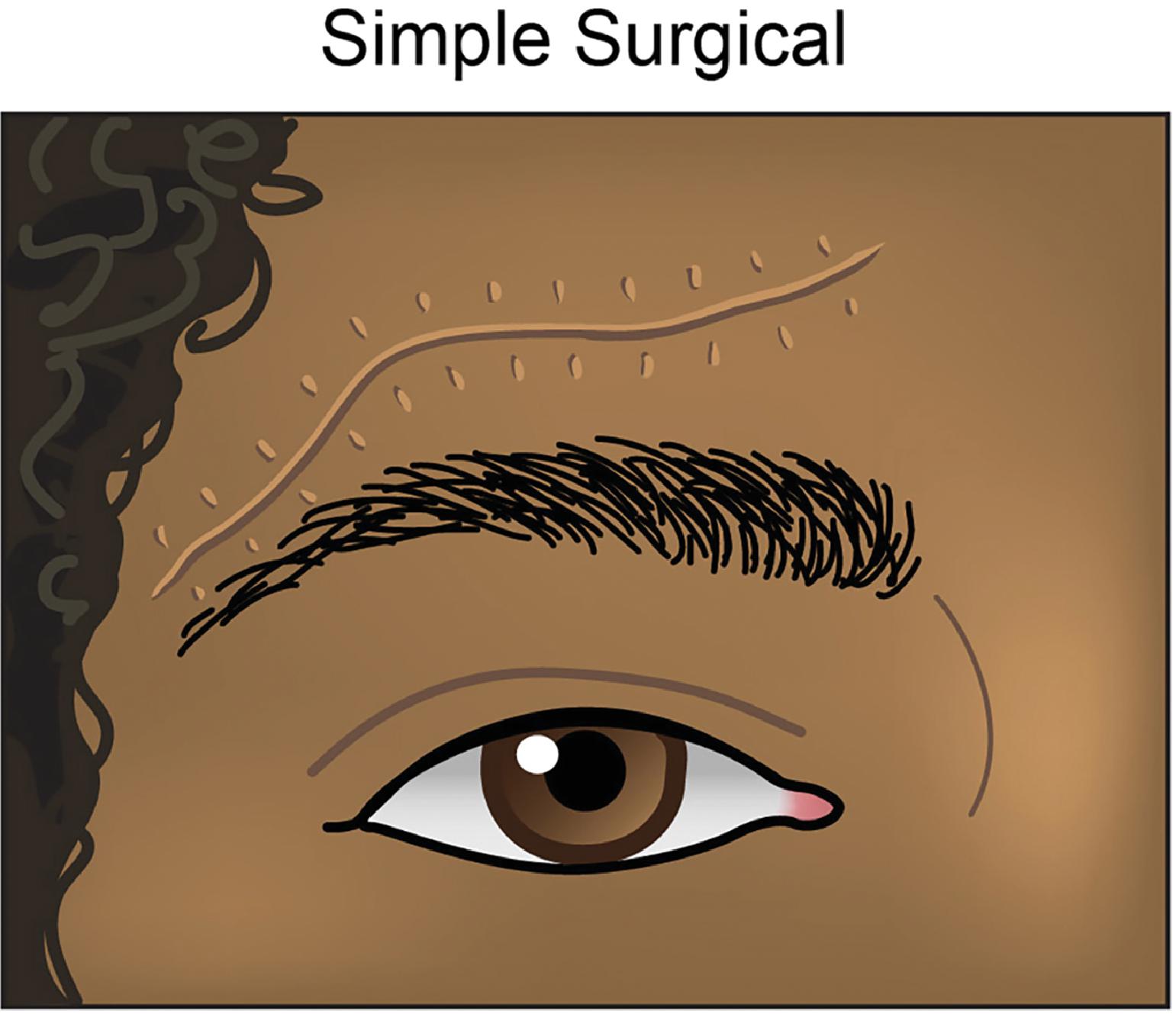

The Simple Surgical Scar

- •

Simple surgical scars ( Fig. 11.3 ) have more favorable treatment outcomes due to more organized wounding and repair.

Fig. 11.3

The Simple Surgical Scar.

Medical illustration courtesy of Sheila Macomber, medical illustrator.

- •

For erythematous, flat surgical scars, early treatment with PDL or KTP/LBO lasers is recommended.

- •

For hypertrophic surgical scars in the early postprocedural period, treatment with low-energy and low-density nonablative fractional lasers (NAFL) is preferred over ablative fractional lasers (AFL) to reduce risks of potential scar destabilization and worsening.

- •

Intralesional (IL) triamcinolone acetonide (TAC) mixed 1:1 with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) can be added to treat the hypertrophic component.

- •

When combining lasers and injectables, it is recommended to treat the scar with the laser or energy-based device first.

- •

PDL and NAFL can be performed alone or during the same session at 4- to 6-week treatment intervals.

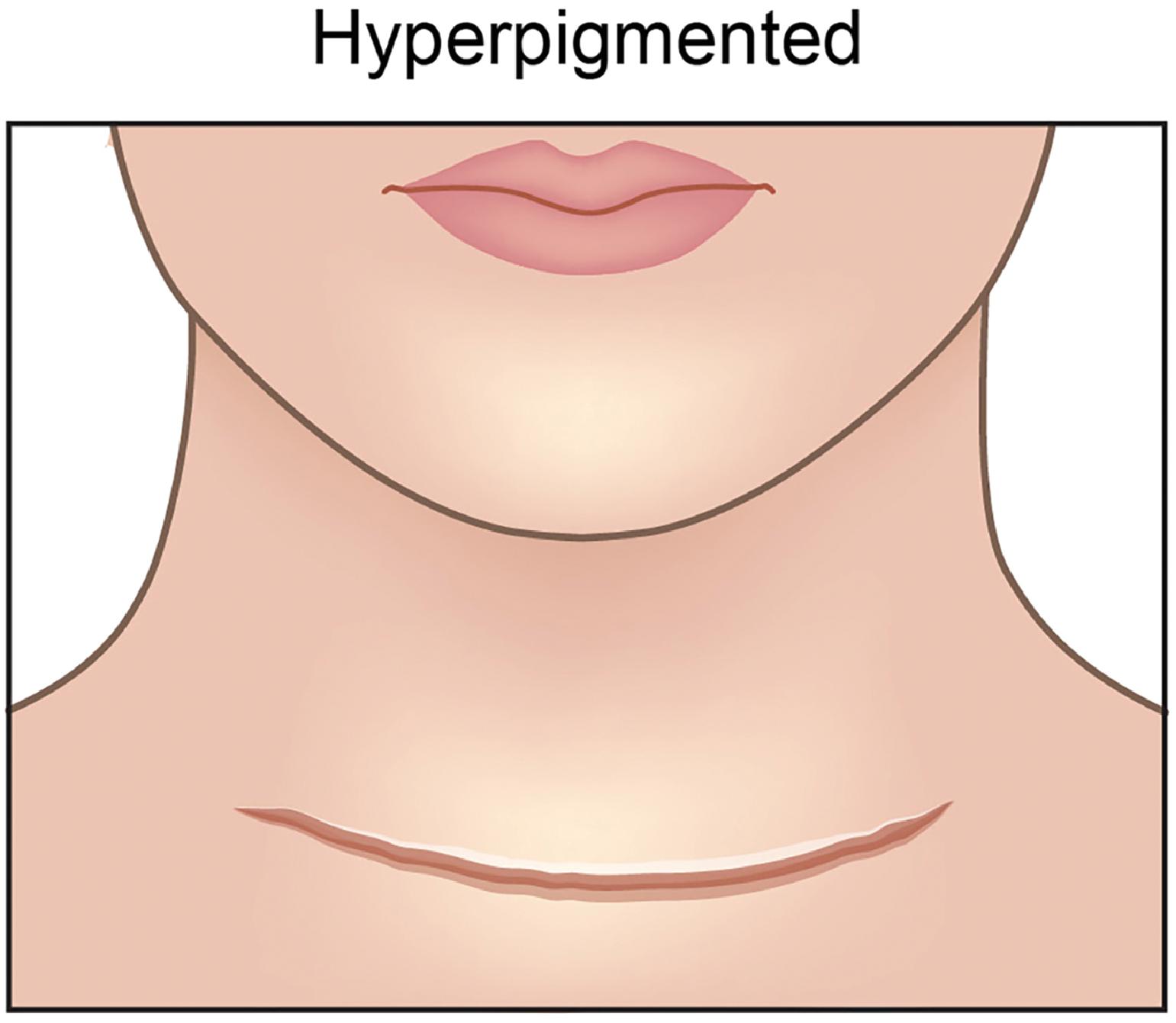

The Hyperpigmented Scar

- •

For hyperpigmented scars ( Fig. 11.4 ), bleaching creams such as low-potency hydroquinone (4%) alone or the triple combination of low-potency hydroquinone, moderate-potency topical corticosteroid, and tretinoin can be trialed first or in conjunction with laser treatment.

Fig. 11.4

The Hyperpigmented Scar.

Medical illustration courtesy of Sheila Macomber, medical illustrator.

- •

Laser management with quality-switched (QS), nanosecond (NS) or, more effectively, picosecond (PS) lasers may be used to clear pigment.

- •

The target chromophore is typically melanin or, less commonly, hemosiderin. The clinical endpoint is immediate epidermal whitening. This endpoint is most apparent with initial treatments. Given decreased chromophore with subsequent treatments erythema and dermal edema are adequate endpoints.

- •

Hemosiderin and melanin pigment can be improved with a QS or PS ruby (694 nm), QS or PS alexandrite (755 nm) +/– a fractional array tip, or a QS or PS Nd:YAG (1064 nm) laser.

- •

For patients with darker skin types, QS/PS Nd:YAG (1064 nm) should be used to reduce risk of dyspigmentation.

- •

Number of treatments depends on the patient’s skin type and the composition, extent, and size of the pigment.

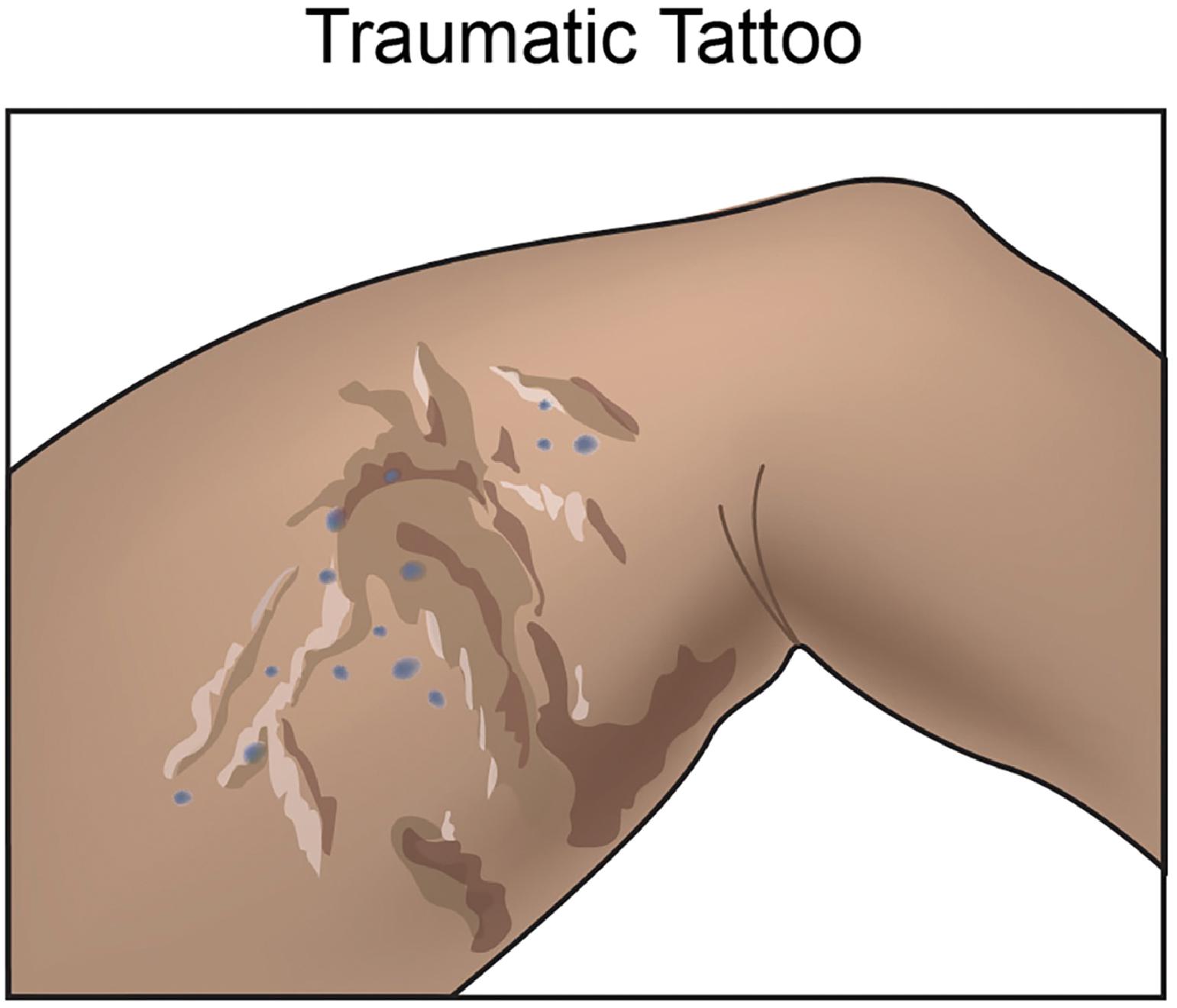

The Traumatic Tattoo Scar

- •

Treatment of scars with embedded traumatic tattoos ( Fig. 11.5 ) is based on similar concepts as treatment of hyperpigmented scars.