Chapter 1 Patient Assessment

A cosmetic surgery patient requires a different evaluation from the patient who is seeking a reconstructive procedure. Since the former is an elective surgery, decisions regarding the patient’s medical suitability to undergo surgery, patient preparation and selection of a procedure that will successfully fulfill the aesthetic objectives must be approached with more scrutiny every step of the way.

Summary

Introduction

Careful listening to the patients’ statements, exploration of their reasons for surgery and their expectations from the surgery, may lead the surgeon to suspect that a patient may have, at least, unrealistic expectations from the surgery or even perhaps body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Visits to numerous plastic surgeons’ offices, having undergone multiple surgeries with resultant dissatisfaction and/or disparaging remarks about the previous surgeon should alert the examining surgeon to the need for exercising more caution, analyzing the patient’s emotional stability more in depth and, if deemed necessary, seeking consultation from a psychiatrist or a psychologist, especially when a depressive or dysmorphic type disorder is suspected. A morose, tearful patient who sees only the negative aspect likely suffers from a depression, while the patient with BDD either sees a deformity that does not exist or sees a great deal more than is present (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Alarming clues suggestive of further patient assessment or avoidance of surgery

| You have an uncomfortable feeling about the patient |

| Patient exhibits clinical signs of emotional instability |

| Patient’s expectations seem unrealistic |

| Patient’s objectives are in conflict with your aesthetic judgment |

| Patient provides you with deceitful information |

| Patient demands guarantees |

| Patient makes disparaging remarks about the previous surgeon |

| Patient asks you to take part in keeping the truth about surgery from the spouse |

| Patient treats you or your staff disrespectfully |

| Patient appears to have difficulty comprehending the recommended course |

The mean age of BDD onset is 16.4 ± 7 years, although most patients don’t seek treatment until their late thirties.1,2 The course of the disorder tends to be continuous rather than episodic and complete remission of symptoms appears to be rare, even after treatment. The disorder appears to affect men and women with equal frequency.2,3 Male patients may be more likely to be unmarried.

Clinical features of BDD include varying degrees of preoccupation with perceived defects. Men may become preoccupied with their genitals, height, hair and body build, whereas women typically report concerns with their weight, hips, legs and breasts. Some patients may present with highly specific concerns (e.g. perceived asymmetry of a body part), whereas others may have vague complaints (e.g. concern that a body part just does not look right). Rhinoplasty, liposuction and breast augmentation are among the most frequently sought surgical procedures by the patients afflicted with BDD.4,5 Seven to fifteen percent of cosmetic surgery patients meet criteria for BDD.

Medical History

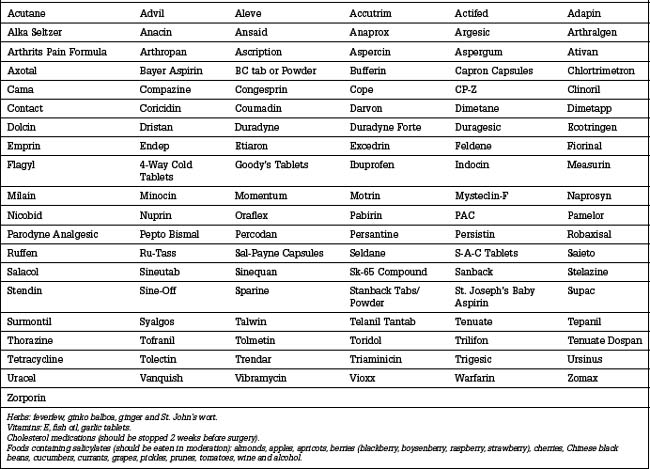

Consumption of prescription, over-the-counter or herbal medications should be investigated carefully (Table 1.2). These may have deleterious effects on surgery and recovery by causing intraoperative bleeding, subsequent hematomas and delayed healing.

Patients in the age group of 50 years or older, and those with known medical conditions that could potentially increase the risk of surgery, should undergo a full medical check up, or an ophthalmology examination within 1 year of surgery if eyelid surgery is being considered.

The most common medical condition that may have deleterious influence on an aesthetic surgery outcome is hypertension. Undoubtedly, controlling the hypertension plays a prodigious role in reducing the risk of postoperative hematoma development. The patient’s blood pressure must be normalized during the several weeks before surgery. If the patient is consuming medications that may contract the blood volume, the surgeon must exercise caution for any developing intraoperative hypotension and, if it occurs, it should be corrected before the incisions are closed. Otherwise, hypotension prevents visualization of the transected blood vessels since they do not bleed, which can start bleeding when the blood pressure rises to the normal level post operatively. In other words, it is the relative hypertension that may cause postoperative hematomas.6

Diabetes is another condition that may lead to postoperative complications.7 Patients with a positive family history of diabetes may have a weakened immune system without clinical or laboratory evidence of diabetes, causing infectious complications that would not otherwise occur under ordinary circumstances. A history of recurrent infection or poor healing on a patient with a family history of this condition, may aid in diagnosing previously undetected diabetes.7 When diabetes is suspected and the fasting blood glucose levels are normal, a simple glucose tolerance test can help uncover an unrecognized diabetes. History of easy bruising or prolonged bleeding, if no pharmaceutical products which can cause bleeding have been consumed, should raise the suspicion of some type of coagulopathy, such as Von Willebrand’s disease.7a

Facial Analysis

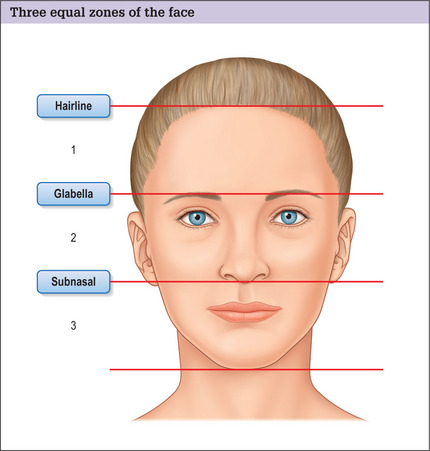

In this chapter we will focus on facial analysis in detail. Analysis of the other parts will be incorporated within the related chapters. To analyze the face in an organized manner, the face is arbitrarily divided into three anatomic zones by three imaginary horizontal lines. The upper line lies at the hairline; the second is at eyebrow level; and the lower line passes through the columella-labial junction (Fig. 1.1). In a comely face these three horizontal lines divide the face into three equal sections. The components of these three zones are appraised individually from frontal and profile views, and likewise the relationships between these units are examined.

Front view of the upper zone

The harmony of the upper aesthetic unit can be marred by a highpositioned hairline, leading to an elongated forehead. This finding is of particular significance when planning the incision for forehead rejuvenation on a patient with a senescent forehead (Fig. 1.2). When the forehead is long, the surgeon may forego a coronal incision or an endoscopic forehead rejuvenation and choose a pretracehial incision, using either the subcutaneous or subgaleal dissection to reduce the forehead height.8,9

Deep wrinkles in the forehead area are commonly the result of compensation of the frontalis muscle to minimize the effects of eyebrow or eyelid ptosis (Fig. 1.3). Thus, it is critical for the surgeon to relax the forehead before selecting a forehead rejuvenation procedure. This can often be accomplished by asking the patient to smile. Usually a compensatory elevation of the eyebrow is eliminated while smiling. The second approach is to ask the patient to close the eyes tightly, and then gently start opening the eyes until the patient can see the viewer. The compensation will become evident as soon as the patient is asked to open the eyes at libre. Analyzing the type of existing wrinkles also aids in choosing a more effective forehead rhytidectomy procedure. In general, deep forehead wrinkles do not respond as favorably to a subgaleal forehead rhytidectomy or an endoscopic forehead rejuvenation. A subcutaneous approach may produce a more successful result in patients with pronounced forehead wrinkling.10 A combination of endoscopic forehead rejuvenation and laser resurfacing is a logical choice for those who exhibit eyebrow ptosis and many fine wrinkles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree