PSORIASIS

Psoriasis is an autoimmune skin condition that affects 2% to 5% of the world population. There is no race that is spared from this disease, although there is a lower incidence in African Americans for unknown reasons. It is equally present among males and females, and onset can occur at any age; however, it is most likely to appear between the ages of 15 and 30 years. Approximately one third of patients with psoriasis have a first-degree relative affected with the disease, and most experts agree that there is strong evidence to demonstrate a genetic family link.

Medications such as β-blockers, lithium, and antimalarials have been associated with inducing psoriasis. Emotional stress, streptococcal and other bacterial infections, and viral infections, such as HIV, can initiate psoriasis as well as inducing flares of the disease. Interestingly, psoriasis has also been triggered by surgery or trauma, with the resulting initial plaque occurring directly over the injury or incision (Koebner phenomenon).

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous symptoms of psoriasis can occur in several forms and is subsequently named based upon clinical presentation.

Plaque psoriasis

The thick, red plaques of classic

plaque psoriasis affect approximately 80% to 90% of patients. Plaques can range from a violaceous red to pinkish red which may be covered with a thin or thick adherent silvery scale. Lesions have well-demarcated borders and occur anywhere on the body, but typically favor the scalp and extensor surfaces of the knees and elbows (

Figure 5-1). This is compared to eczema, which favors flexural surfaces and is typically not well-demarcated. Removal of scale from a psoriasis plaque will reveal punctate blood vessels that bleed (

Auspitz sign) and aid in the clinical diagnosis of psoriasis. The severity of disease can range from limited scalp involvement (mild disease) to widespread or severe disease involving greater than 5% of the body surface area (

Figure 5-2).

Scalp psoriasis

Scalp psoriasis, which often appears as a “cap” of thick, silvery, adherent scale on an erythematous (even violaceous) base, can be a very challenging form of psoriasis and is often mistaken for seborrhea or seborrheic dermatitis (SD) (

Figure 5-3). Scalp psoriasis can be a particularly distressing manifestation for patients due to the visibility of the plaques, the significant pruritus, and the extensive scaling that sheds on clothing.

Palmoplantar psoriasis

Psoriasis can be localized on the palms and/or soles in a condition known as palmoplantar psoriasis. Lesions can present as erythematous papules, patches, deep-seated vesicles, and pustules. Fissures can form on the palms and fingers, along with dystrophic nail changes. Because of the pustular nature of this type of psoriasis, many providers may conclude that it is a bacterial or viral infection; however, culture of these sterile papules does not reveal any microorganisms.

Guttate psoriasis

Guttate psoriasis occurs in 2% of patients with psoriasis who are usually younger than 30 years, and is characterized by round 1-to 10-mm, salmon-pink papules (“dew-drops”) with a fine white scale (

Figure 5-4). In many cases, it is preceded by a streptococcal throat (strep throat) or sinus infection; however, the pathophysiologic association between the infection and disease is not clearly understood.

Inverse psoriasis

Psoriasis that occurs in the intertriginous areas of the skin is called inverse psoriasis and is often mistaken for a fungal or candidal infection. These conditions can present as thin, erythematous, shiny patches with little to no scale. The folds of the axillae, groin, and intergluteal, and inframammary areas are the most common locations. It is not unusual for patients to be treated with topical antifungals for months before making the diagnosis of inverse psoriasis.

Erythrodermic psoriasis

A more severe form of psoriasis which presents with full-body (>90% BSA) erythema and scaling is referred to as

erythroderma (

Figure 5-5). This condition may be triggered by environmental factors or as a response to medication. Interestingly, patients with plaque psoriasis who may be treated with systemic corticosteroids may show an initial remission, and then experience a severe “rebound,” resulting in erythrodermic psoriasis. Most dermatology providers do not treat any form of psoriasis with systemic corticosteroids for this very reason. Patients with erythroderma often require hospitalization and are quite ill.

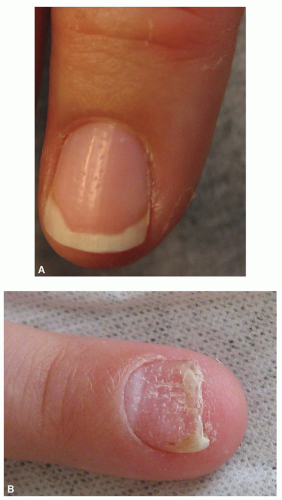

Psoriatic nails

Most patients with psoriatic disease have finger and toenail involvement. Thickened, dystrophic, and yellow nails, which may separate from the nail bed, are often mistaken for fungal disease. In more subtle involvement, pinpoint “pitting” may be observed and is classically associated with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) (

Figure 5-6). “Oil spots” are a nail finding in some patients with psoriasis and present as pink or tan round areas within the nail. Nail involvement can be incredibly disfiguring as well as painful for patients, and presents a challenge for providers to manage (

Figure 5-7). Severe dystrophy of the nails may require removal of the entire nail and nail matrix in order to alleviate painful symptoms.

Comorbidities

Psoriasis was initially believed to be limited to the skin. However, because it is an immune-mediated disease, it is now clear that the inflammation that occurs in the skin can also be found in other systems, including the joints, heart, brain, and other organs. Patients with more severe psoriasis have shown an increased incidence of joint disease (psoriatic arthritis), cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and other immune-mediated conditions such as Crohn disease. Additionally, there are numerous psychological disorders that can be associated with psoriasis, including depression, increased risk of suicide, alcoholism, and social isolation.

Understanding the concept that psoriasis is associated with other inflammatory diseases is critical for two reasons. First, it heightens the clinical suspicion of practitioners to screen patients with psoriasis for associated comorbidities as soon as psoriasis is diagnosed (

Table 5-1). Second, the education and prevention of these diseases can start earlier in life.

Cardiovascular disease

Patients with severe plaque psoriasis may be self-conscious of their appearance and therefore avoid participating in exercise or social activities. The lack of physical activities can result in increased weight gain, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic pain syndromes. Conversely, the chronic inflammatory nature of psoriasis itself may lead to other inflammatory conditions such as cardiovascular disease and myocardial infarction.

Metabolic syndrome

Studies have demonstrated that there is an increased risk of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis. Clinicians should assess psoriatic patients for the coexistence of disorders, which include obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, and prothrombic and proinflammatory state. Metabolic syndrome raises an individual’s risk for heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

Depression

One quarter of patients with psoriasis suffer from depression. Social isolation may contribute to increased risk of depression and anxiety, smoking, alcoholism, job instability, and financial problems. In addition to depression, patients with psoriatic disease often contend with low self-esteem and chronic pain issues. Patients report difficulties maintaining relationships due to fears of being ostracized because of their skin disease. Young patients often fear participating in sports or social events as they are concerned their peers may think that their condition is “contagious.”

Malignancy

The increased risk of cancer in patients with psoriatic diseases is controversial. Because psoriasis is an immune-mediated disease, some psoriasis experts hypothesize that this may be associated with an increased risk of lymphoma and solid tumor cancers. Although phototherapy with narrow-band ultraviolet radiation is a common treatment for skin psoriasis, it has a low but nonetheless significant risk for the development of squamous and basal cell carcinomas. Lastly, the overall increased risk of smoking and alcohol use in patients with psoriasis makes it difficult to determine whether these factors also contribute to cancer risk rather than the psoriatic disease itself.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriasis is typically identified as a skin disease, yet approximately 10% to 30% of these patients develop associated joint disease referred to as PsA. The inflammatory mechanisms that form thickened skin plaques also result in bony destruction and overgrowth in joints. Patients with PsA suffer from significant joint pain and dystrophy. In addition to examining the skin, it is imperative that the clinician obtain a thorough history of joint pain and family history of rheumatologic diseases, as well as conduct a physical examination of hand and foot joints. Patients may have dactylitis (sausage digits), asymmetrical oligoarticular (few joints) arthritis, distal interphalangeal arthropathy, and joint deformity (

Figure 5-8). Patients with psoriasis should be assessed yearly and if PsA is suspected, should be referred to rheumatology. Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment with systemic therapies can prevent permanent joint destruction and significantly improve the quality of life (QOL) for psoriatic patients.

Diagnostics

Psoriasis is usually a clinical diagnosis after conducting a detailed patient history, physical examination, and documentation of their medication (prescribed and over-the-counter). In more complex or atypical presentations, a punch biopsy of the affected skin can aid in the diagnosis. Laboratory studies are usually not helpful in diagnosing psoriasis but are critical in identifying comorbidities. Radiology studies are indicated if the patient is suspected of PsA.

Equally important in the assessment and diagnosis of a patient with psoriasis is the perceived impact on their QOL from psoriatic disease. QOL can be measured with a 10-point questionnaire, Dermatology Life Quality Index (www.dermatology.org.uk). A clinician may diagnose the patient with mild cutaneous disease; however, it may be incredibly distressing for the patient. Of course, screening tools for depression, anxiety, and substance abuse should be utilized when there is clinical concern.

Management

Unfortunately, there is no cure for psoriasis, and control of the disease is the goal of management. Once diagnosed, treatment of the psoriasis patient is focused on symptom management, disease control, reducing the risk for comorbidities, and optimizing QOL. Developing a plan of care for a psoriasis patient should consider the type of psoriasis, location, severity and extent of disease, age, symptoms and comorbidities, response to previous treatments, pregnancy (or intent) and lactation, access to treatment facilities, economic factors related to insurance coverage and cost of care, and QOL. The severity of the disease can be a starting point for the clinician in selecting appropriate treatment options. Here are some guidelines.

Mild-to-moderate psoriasis

Most primary care providers who have a basic understanding of psoriasis should feel comfortable treating mild-to-moderate skin disease. Good skin care including emollients should be employed even before prescribing therapy. Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are the

first-line treatment for mild disease; however, patients should be warned about the side effects with prolonged use (see

chapter 2). Use of TCS should be avoided or limited on the face, axillae, and genitals. Topical immunomodulators (TIMS) are often selected for treatment in these areas.

Reevaluate adult patients in 4 weeks and children in 2 weeks, to assess their response to therapy. If there is an inadequate response, evaluate the patient’s understanding and use of TCS, consider changing the class of TCS, or add another topical agent (TCS chart on inside of back cover).

Vitamin D derivatives can be used as adjuvant topical therapy and are safe to use in steroid-sparing regions; however, they may cause some skin irritation initially. Coal tar has been used for centuries to treat psoriasis but is less common now; it decreases the rapid proliferation of skin and reduces inflammation. It can be very effective for controlling the itch associated with psoriasis. Keratolytics help thin the plaques of psoriasis and improve the penetration of TCS (

Table 5-2).

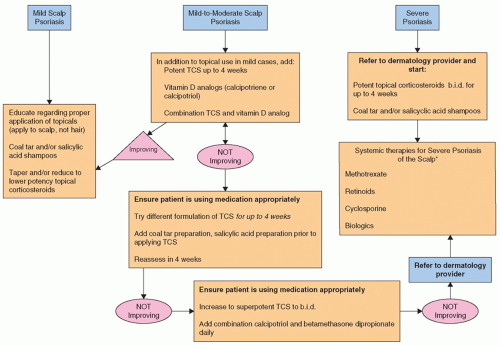

Management of scalp psoriasis can be frustrating for both the patient and the clinician (

Figure 5-9). The first-line treatment for scalp psoriasis is the initiation of topical therapies at the first sign of erythema, scaling, or scalp pruritus. Tar preparations, salicylic acid, and oils are recommended for mild disease and are now available in easier-to-use shampoos, solutions, gels, and foams. Some are used as overnight applications for a greater effect. Mild-to-moderate scalp

involvement may require the addition of TCS, vitamin D analogs, or both. Patients should be advised not to pick or scratch the scale of their scalp, which puts them at increased risk for infection. Scalp psoriasis that is severe should be referred to a dermatologist.

Moderate-to-severe psoriasis

Moderate-to-severe psoriatic disease warrants a referral to a dermatology practitioner experienced in psoriasis care. The definition of “moderate to severe” has varied definition and complicated metrics that are used in clinical trials, but are not very practical in primary care. For the purposes of this text, the parameters of moderate-to-severe psoriasis and indications for referral are outlined in

Table 5-3.

Phototherapy can be a very effective modality for moderate or severe psoriasis. However, if phototherapy is not available or effective, systemic therapies must be considered. These traditional agents have been utilized in the management of psoriasis for decades; however, they do pose significant health risks, not limited to, but including liver, kidney, cardiovascular, and blood dyscrasias.

Biologics are the newest therapeutic agents for the management of moderate-to-severe psoriasis and with some also indicated for the treatment of PsA. These systemic agents directly target specific chemical mediators within the immune systemic that are associated with psoriatic disease.

Table 5-3 provides an overview of treatment options in the management of moderate-to-severe psoriasis. These agents should be prescribed and managed by a dermatology provider.