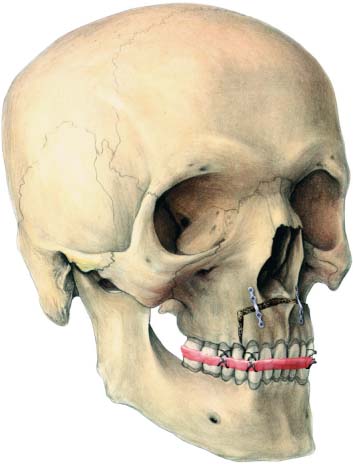

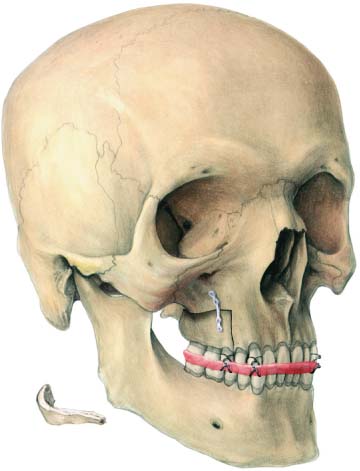

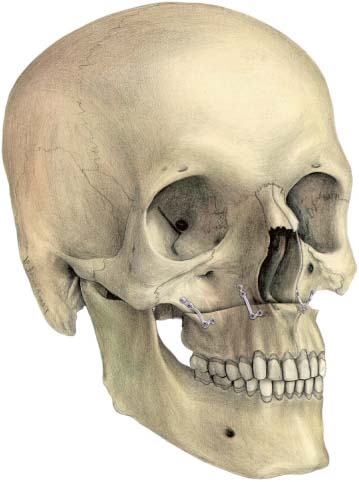

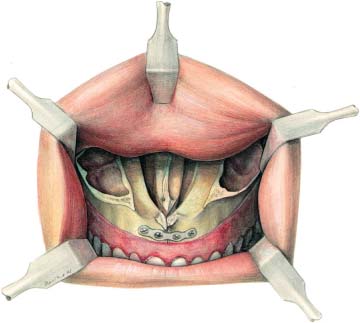

23 Osteotomies of the Maxilla The anterior maxillary segmental osteotomy described by Wassmund (1935a) and Wunderer (1962) was one of the most frequently used osteotomies to set back the anterior segment of the maxilla in cases of dentoalveolar protrusion. With the increased cooperation between orthodontists and surgeons, the need for these osteotomies has been drastically reduced. Yet, there are still indications for performing an anterior maxillary segmental osteotomy, particularly when vertical movements are required or when asymmetries need to be corrected. Miniplates may play an important role in stabilizing the anterior segment. Both the Wassmund and Wunderer approaches include a distally curved but basically vertical incision in the buccal vestibule. This usually provides sufficient access to apply a four-hole plate on each side to stabilize the fragment. Attention should be paid to the location of the root tips of the canines and bicuspids in order not to make burr holes in these roots. There is usually room for one plate on each side, which provides enough stability, particularly when an acrylic splint is wired in place (Fig. 23.1). Fig. 23.1 Anterior segment secured by two four-hole plates and an acrylic splint wired to the maxillary teeth. The bilateral posterior maxillary segmental osteotomy, introduced by West and Epker (1972), to close the anterior skeletal open bite is rarely used anymore, because tilting osteotomies on a Le Fort I level have largely replaced this technique. The posterior maxillary segmental osteotomy, however, has several other indications. It may be used to close gaps in the alveolar process when teeth are missing, or to correct asymmetries in the arch form in any direction. The technique is most useful, however, when the lesser fragment in patients with cleft lip and palate needs to be repositioned. Miniplates, but especially microplates, are almost indispensable for stabilizing the fragment. The technique most commonly used entails a buccal mucoperiosteal pedicle as the main blood supply to the fragment. This implies that a relatively small vertical incision can be made which, of course, limits the access. After completion of the osteotomy through a palatal incision, the fragment is maneuvered into place and fixed to the main fragment using an acrylic splint. A suitable four-hole microplate is selected, which may be straight or L-shaped. In most cases only one microplate can be placed, fixed with 4 mm or 6 mm long screws. Defects resulting from positional changes of the segment should be grafted, preferably using autogenous bone. One plate does not provide enough stability, but in combination with an orthodontic arch wire or acrylic splint, or both, stability is usually adequate (Fig. 23.2). Fig. 23.2 Posterior segment secured with one four-hole micro-plate and an acrylic splint wired to the maxillary teeth. The Le Fort I osteotomy, first described by Wassmund (1935b) and later standardized by Obwegeser (1965) and Bell (1975), has become the most frequently used osteotomy in the maxilla. This osteotomy allows for almost any movement of the tooth-bearing area of the maxilla including advancement, caudal and cranial positioning, tilting, and rotation in a horizontal plane. All these movements can be achieved fairly easily, and often two or even more directional changes can be accomplished at the same time. Narrowing or widening of the arch can also be accomplished by extra palatal cuts. The only movement not easily achieved is a setback, since it implies cutting away bone in the tuberosity area or pterygoid plate. The stability of Le Fort I osteotomies using wire osteo-synthesis is adequate, particularly if advancement and intrusion is the main purpose. When extrusion is wanted, however, the stability is far from acceptable. Furthermore, it is difficult (if not impossible) to predict the extent of any relapse that will occur, even if bone grafts are used. Miniplates and microplates have also proven to be highly successful in providing stability in cases of extrusion of the maxilla (Baker et al., 1992). This is particularly important when carrying out bimaxillary surgery, where postoperative positional changes of the maxilla can be detrimental to the final result. Since the application of miniplates and microplates is simple and quick, a further advantage of using them to stabilize the fragment is a considerable reduction in operating time. A Le Fort I osteotomy is performed in the usual fashion and the fragment is temporarily secured by intermaxillary fixation. The mandibular–maxillary complex can then be placed in the desired position, but attention should be paid to avoid pulling the condyles out of the fossae when rotating the mandible. If this happens it usually requires bone to be trimmed in the posterior area of the osteotomy. This mistake is particularly prone to happen when intrusion is the main objective. The plates can best be fixed at the zygomatic buttress and alongside the piriform aperture, since the bone in these locations is usually thicker than in the canine fossa. Miniplates or microplates are bent to follow the curvature of the bone structures or to accommodate discrepancies that may exist in a transverse or anteroposterior plane. Two straight, four-hole or L-shaped plates on each side are usually sufficient to adequately stabilize the maxilla (Fig. 23.3). An additional plate, placed horizontally under the piriform aperture, may be necessary in the case of midline splits to adjust for transverse discrepancies. This plate can be bent under the nasal spine (Fig. 23.4). The same applies when simultaneous segmental osteotomies are performed in the bicuspid–molar area. Bone grafts should be used when defects are apparent after repositioning of the fragment. This is particularly important when the maxilla is moved downward. The blocks are contoured to fit the gaps in the lateral sinus wall and preferably placed with their cortex toward the plates (Fig. 23.5). If necessary, a screw may be inserted in the free bone graft to help to stabilize the graft. Fig. 23.3 Position of four L-shaped microplates with bridges to secure the maxillary segment.

Anterior Maxillary Segmental Osteotomy

Introduction

Technique

Posterior Maxillary Segmental Osteotomy

Introduction

Technique

Le Fort I Osteotomy

Introduction

Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree