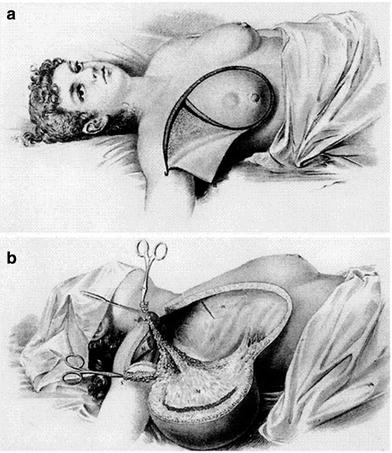

Fig. 1.1

Advanced breast cancer showing fungating lesions extruding through the skin

As far as we can tell, although Hippocrates discussed the potential for removal of the breast, the first documented account of mastectomy is credited to Johan Schultes (1595–1645). However, a detailed description of the operation was only published after his death in 1665 [3–5]. Early mastectomies were made possible with the introduction of surgical instruments that allowed very rapid removal of the diseased tissue. Although the idea of removing the diseased area gained popularity, women often died from bleeding, infection, shock, or anesthetic complications. However, once anesthetic techniques were perfected, and antibiotics became a routine part of surgical regimens, successful removal of the breast was accomplished. As surgeons go, Halsted is most often credited as the innovative surgeon who perfected the technique of radical mastectomy in the USA in 1882. In fact, Halsted achieved a 5 year cure rate of 40 %, which was highly regarded. In addition to his aggressive removal of tissue, other factors likely contributed to this success rate as well, such as his use of antiseptic techniques and his use of rubber gloves. Apparently, Halsted had asked Goodyear to develop gloves in 1889. Other surgeons such as Crile and Haagensen were also important in the consistent move toward innovation in fighting breast cancer through surgery, and the Halsted radical mastectomy was the mainstay of breast cancer treatment throughout most of the last century. In fact, it was used in over 90 % of all breast cancer patients treated between 1910 and 1964 [6].

As we examine the results of the Halsted radical mastectomy (i.e., removal of the entire breast, including much of the skin along with the nipple–areola complex, underlying pectoralis muscles, and the axillary contents), we quickly begin to understand the physical and psychological challenges that women face(d) when deciding to undergo this presumed “life-saving” surgery ( 1.2). Although hundreds of thousands of women have lived through this life-altering surgery, it is clear that the psychological impact on women undergoing mastectomy is profound, and includes body image changes as well as many other emotional challenges that must be addressed in order for successful adaptation to a “new way” of life. Some of the critical issues that most women struggle with after being diagnosed with breast cancer are as follows:

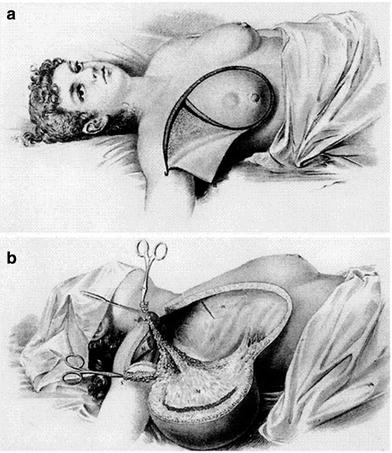

Fig. 1.2

Etchings of Halsted radical mastectomy showing enormous en bloc resection of the breast, underlying muscles, and overlying skin

Fear, anxiety, and stress

Depression

Grief

Body image

Sexuality

Fertility

Planning for the future

Social support system

Each and every woman will weigh differently the priority of these things in their own particular life, but for most women the single greatest challenge is the adjustment to their new body image.

The photograph in Fig. 1.3 shows a woman many years after radical mastectomy of the right breast. In this photograph her body language speaks to us, as it shows her stance with her right shoulder angled upward and forward in a manner suggestive of protecting, guarding, and/or trying to “hide” the area of her mastectomy. Many studies confirm that breast reconstruction assists women in their adjustment to mastectomy; however, it does not eliminate the need for psychological adjustment and, in fact, consideration to undergo breast reconstruction brings with it additional and somewhat different issues for a woman to grapple with (Table 1.1). It is essential for the breast surgeon to be trained not only in the technical aspects of dealing with breast cancer but in the skills to assist women struggling with these difficult and often very delicate psychological challenges as well.

Fig. 1.3

Patient following standard radical mastectomy. Note the body posture with the right shoulder slightly forward as if “guarding” or “hiding” the mastectomy site

Table 1.1

Emotional pros and cons of breast reconstruction

Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

Feel whole again | Fear |

Maintain femininity | Not essential for well-being |

Balanced physically | Too old to matter (i.e., being vain) |

Marital/sexual acceptance | Interfere with treatment |

Avoid embarrassment of prosthesis | Concern about masking disease |

Surgeon’s recommendation | Uncertainty about breast appearance |

Forget about disease | Requires additional surgery, risk of complications |

1.2 Breast Surgery: Evolution of the Science

With women’s advocacy groups forming throughout the 1960 s to 1970 s, social awareness about breast issues and breast cancer began to change dramatically. Just a few decades ago, women were loathe to speak about breast cancer in social circles, whereas today, women take to the streets, gather by the thousands, and celebrate their successes in conquering their battle with breast cancer. This awakening coupled with the “feminist movement” of the 1970 s created an environment for women to begin questioning their “rights” in the treatment of breast cancer. At the time, most women underwent open surgical biopsy with preoperative consent for the surgeon to proceed with mastectomy if the frozen section tested positive for cancer. One can only imagine how traumatic it was for women who faced the uncertainty of waking up from surgery with or without their breast(s). This practice soon came under scrutiny and ultimately called for the standard of care to include a preoperative confirmation of the diagnosis of cancer prior to mastectomy, as well as informed patient consent prior to surgery. There is no doubt that the work of the well-known patient advocate Rose Kushner irreversibly changed history in regard to breast cancer treatment. She was the first breast cancer survivor to bring these issues to Washington, and her efforts led to the creation of legislation that helped fuel many changes in the USA. Her efforts were of paramount importance.

Although surgical removal of the breast was touted as a giant step forward in the treatment of breast cancer, no doubt surgeons and their patients both struggle(d) to accept this method as the “best” possible solution. For decades, a growing consciousness began to form about the possibility of imaging the breast in order to find tumors at an earlier stage. Thankfully, through the development of imaging techniques that ultimately led to screening mammography programs, the diagnosis of smaller and often “earlier” cancers was made possible. Thus, with the advent of modern-day breast imaging and the diagnosis of earlier and often noninvasive tumors, improved survival rates and better treatment options became a reality [7–9]. For the breast surgeon, this included the notion that perhaps surgical treatment need not be so aggressive. In addition, the interaction between physicians in different subspecialties became popular as it was noted that a more comprehensive plan could be developed if and/or when a patient’s treating physicians communicated directly with one another in the best interest of the patient.

As radiologists began to diagnose smaller tumors, surgeons began to modify the techniques of Halsted, and they began saving the pectoralis muscles and more of the overlying skin of the chest. Studies quickly noted that survival rates were equivalent to those for radical mastectomy, and thus the “modified” radical mastectomy became popularized. This huge change in breast surgery was most likely due to the earlier stage of disease at the time of diagnosis, but nonetheless, this changed breast surgery forever. As can be seen in Fig. 1.4 the standard modified radical mastectomy has a typical horizontal scar across the breast area and in most cases does not require a skin graft for closure, which was quite commonly needed with the radical mastectomy.

Fig. 1.4

The left image shows the patient 30 years after bilateral modified radical mastectomies. She requested bilateral reconstructions with nipple reconstructions (central image). Note the horizontal incision limits the ability to get projection in the center of the reconstructed breast, resulting in a somewhat globular shape (compare with Fig. 1.6). The patient’s improved body image and self-confidence is evident in her selection of undergarments as seen in the right image

From here, surgeons began to hypothesize that perhaps the breast tissue itself (including the nipple–areola complex) could be preserved if additional therapy (such as radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy) were administered to help decrease or eliminate the potential for recurrent disease. Of course, the scientific community required classic studies to be performed in order to prove this hypothesis, and through decades of tedious clinical trials, Umberto Veronesi and his clinical group at the Milan Cancer Center ultimately proved the hypothesis. Veronesi’s pioneering work as well as numerous other scientific studies by various surgeons around the world have shown that survival rates for women undergoing breast conservation are equivalent to those having mastectomy if, and only if, many factors are also taken into consideration, such as appropriate selection of patients, wide excision of the tumor with substantial clear histologic margins, and the use of adjuvant therapy (chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy) as needed [10, 11]. Ultimately, with these critical decisions being made in the field of breast surgery and through the extraordinary courage and foresight of innovative surgeons, scientists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and other breast cancer specialists working together, the field of breast surgery began to evolve dramatically and it has never been the same since.

Although the idea of breast conservation surgery became a reality, and surgeons and patients alike hoped that mastectomy would become a distant historical footnote, studies ultimately showed that not all women were truly good candidates for breast conservation. Interestingly, not all women choose breast conservation either, and so mastectomy has remained a mainstay in the treatment of breast cancer. Two important questions remain: How can we best identify suitable candidates for breast conservation, and how can we improve the aesthetic appearance of the breast(s) following mastectomy? In fact, the selection of appropriate patients for the appropriate procedure becomes the critical question for the breast surgeon’s judgment.

Given today’s current imaging techniques, as well as other sophisticated methods to assist with patient assessment such as genetic testing, the selection of appropriate patients has become much more comprehensive and precise. Today, preoperative assessment is the cornerstone of effective, efficient, and appropriate breast surgery and it is a vital expertise that the breast surgeon must be able to offer in order to provide optimal care to patients. The principles of oncoplastic surgery within the multidisciplinary framework for preoperative assessment of patients can be summarized as follows:

Primary diagnosis, extent of disease, and risk assessment prior to surgical intervention

Psychosocial needs and desires of the patient

Surgical planning to include resection and reconstruction options

En bloc tumor resection (with wide margins) and intraoperative margin assessment if possible

Marking of tumor bed margins for adjuvant radiation and follow-up

Axillary node sampling (sentinel node)

Need for adjuvant treatment (type and timing)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree