Nose

BIOANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

Together with the eyes the nose forms the centerpiece for initial impression. It has a complex three-dimensional structure, and its skin is nonuniform. With its many distinct forms, the nose is among the most challenging sights for surgical reconstruction, and one of the most rewarding.

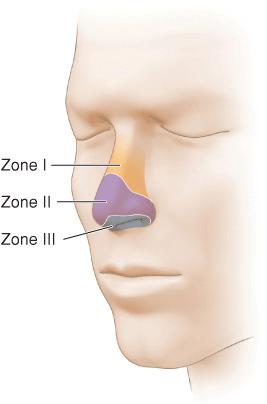

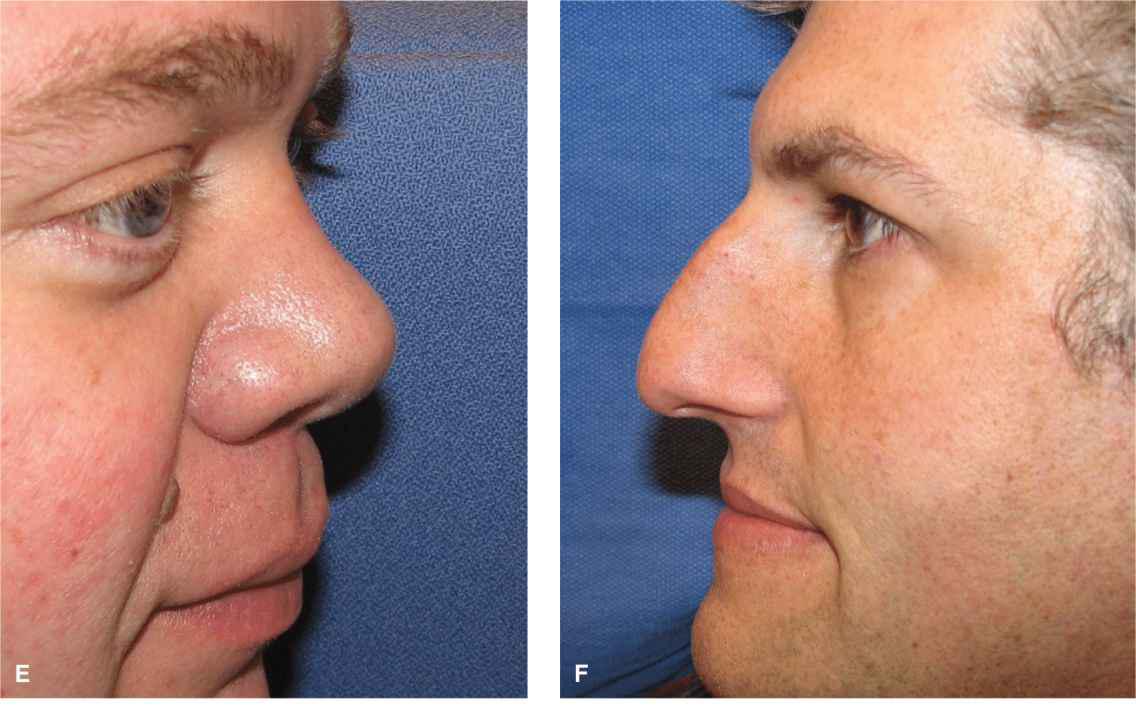

The takeoff point of the nose is from the nasion. From this point, the nasal bone extends inferiorly and anteriorly. The majority of the nose is composed of cartilage, fascia, muscle, and skin. The structure of the upper nose rests on the upper lateral alar cartilages. The lower nose is supported by the columella and the lower lateral alar cartilages. Biomechanically, the nasal tissues are relatively inelastic. The upper nose tends to have thin, nonse-baceous skin. The lower nose is more sebaceous. The very tip of the nose and the columella are often thinner and less sebaceous as well. These three zones of nasal skin are identified as type I, II, and III1 (Fig. 7.1). They do not exist in a predictable location and transition variably. Some individuals have thin, mobile type I skin on the majority of the nose, while others—particularly older men—have a thick sebaceous quality of almost all of the nasal skin. In these individuals, reconstruction with local flaps can be particularly challenging due to the inherent visibility of complex surgical scars. The bony/cartilaginous structure of the nose is lined internally by a loose, thin, subcutaneous tissue and mucosa. The external surface of the upper and mid nose is lined by epidermis, dermis, a thin loose superficial fascia, a layer of nasals muscle, and a thicker multilayer inframuscular fascia.

Figure 7.1 Three types of skin are present on the nose. The type 1 skin of the nasal bridge and upper nose is less sebaceous and more mobile. Type 2 skin is present on the alae and distal nose. It is thicker and sebaceous in nature. Type 3 skin lines the nares, columella, and soft triangle. It is thin, less sebaceous, and relatively immobile

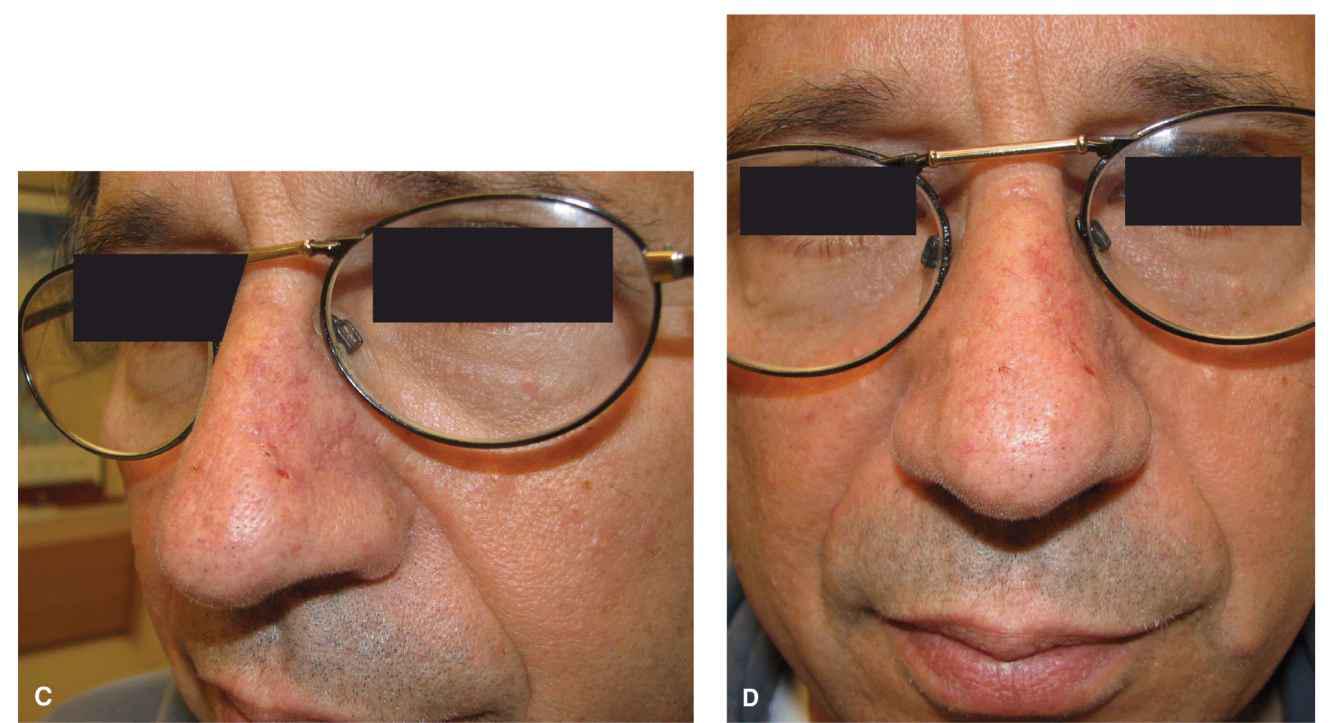

The shape of the nose varies dramatically (Fig. 7.2). Hooked or so-called Roman or Aquiline noses have a very prominent convex shape with a shaper nasal spine. The hawk nose is an accentuated hooked nose, with a very thin side-to-side profile. The Greek or straight nose has no curve to it, proceeding straight from the nasal spine to the tip. The Nubian nose starts thin at the upper bridge and widens and enlarges in thickness toward the wide open nares. This nose type is common in African Americans. The pug nose is a short slightly concave nose, with a flattened tip. The upturned or celestial nose is a long, thin nose with an upwardly projected tip, often with large, prominent lower lateral alar cartilages. Each such nasal subtype presents a different challenge to the reconstructive surgeon. For example, the sharp, convex nasal bridge of a hawk nose conveys substantial wound tension to a side-to-side closure, and its shape is accentuated by such repairs. This can exaggerate the existing hump and result in a beaked appearance. Alternatively, an upwardly projected tip with large, prominent alar cartilages and tense, thin overlying skin can preclude the use of smaller local flaps owing to resultant free margin distortion. For that matter, any repair on the nose that places too much tension in a vertical direction can result in free margin distortion, alar asymmetry, or tip elevation.

Figure 7.2 Noses vary tremendously in size, shape, and texture. (A, B) Elegant nose. The nose is thin with well-defined symmetric alae. Only the distal nose is sebaceous. On lateral view, the wing of the nose is very well defined and the bridge is a straight line. In repairing such a nose, it is imperative to maintain or recreate the well-defined deflections of the alar creases. (C) The nose is similar to A/B but slightly more full and flatter distally. (D, E) A more sebaceous nose with an upturned tip. This common nasal subtype presents a challenge to repair as the sebaceous tissues are relatively immobile and scars tend to be more visible. (F) Classic Roman nose with prominent nasal bridge seen on lateral projection. When a midline linear repair is performed, it will accentuate the triangular peak. (G, H) Prominent lower lateral alar cartilages are noted and create a distinctive appearance. This type of nose is challenging to repair with local flaps and will often be best reconstructed with an interpolated subunit approach. (H, I) In this postrhinoplasty nose, the skin is relatively nonsebaceous but also relatively immobile. The alae are thin but well defined. The lower lateral alar cartilages are prominent. Local tissue rearrangements on the lower portion of such a nose are challenging

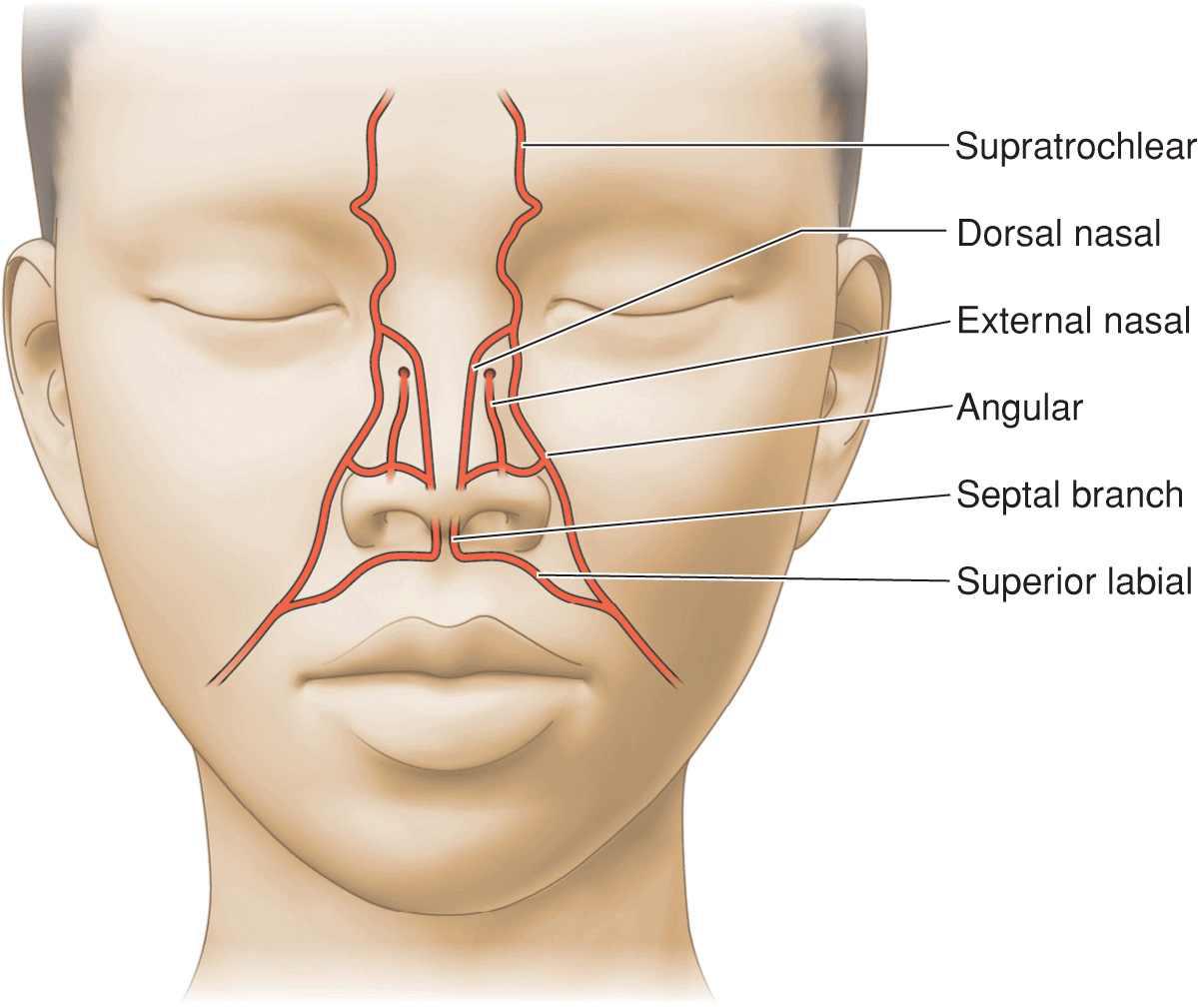

The nose is supplied by a rich, anastomotic plexus of vessels originating from both the external and internal carotids (Fig. 7.3). The facial arteries reach the nose as the angular arteries, passing just lateral to the nasalis. At this point, they supply a large branch to the nose that ascends to the midline nose within or along the inferior belly of the nasalis muscle. The dorsal nasal arteries extend from the distal branches of the ophthalmic and ethmoid arteries, emerging from the skull close to the origin of the medial canthal tendon. They extend distally just below or above the medial fibers of the nasalis musculature. The columella is supplied by its own branch, which ascends from the superior labial arteries.

Figure 7.3 The nose is richly supplied with redundant vasculature from the facial arteries and the internal carotid system

The main vessels supplying the nose anastomose broadly and have many small branches. In aggregate, they supply the nasal tissue with a robust blood supply. Flaps elevated in the loose deep fascial planes beneath the major vessels benefit from this predictable vasculature, and as a result, local adjacent tissue transfers on the nose can rotate and move substantial distances while maintaining viability. There are no significant motor nerves on the nose. Sensory input to the nose is from the supratrochlear, infratrochlear, external nasal, and infraorbital nerves. Nerve blocks of the infraorbital nerve provide dense anesthesia of much of the ipsilateral ala, but other areas of the nose require multipoint anesthesia with local infiltration. The external nasal or nasociliary nerve is particularly vulnerable toward its distal extent and is frequently transected with adjacent tissue transfer completion. Numbness of the distal nose is frequent following reconstruction, but restoration of sensation is usually seen at 1 year.

While the reconstructive surgeon is often concerned with form, the nose has a substantial function as well. Airflow through the nasal valve must be smooth and effortless, and repairs that cause stenosis or collapse of the nasal valve can fail even as the external appearance is satisfactory. For that reason, attention to the three-dimensional structure of the nose is imperative in nasal reconstruction.

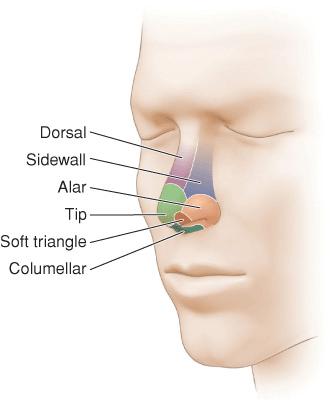

In the last several decades, a great deal of attention has been placed on anatomic subunits in nasal reconstruction. For this purpose, the nose is divided into nine subunlts: a dorsal subunlt, two sldewall subunlts, a tip subunlt, two alar subunlts, a columellar subunlt, and two soft tissue triangle subunlts2 (Fig. 7.4). For larger wounds, especially those requiring interpolated pedicle flap repair, surgical reconstruction of an entire cosmetic subunit—even if it Involves enlarging the defect—can produce a very aesthetic outcome. When feasible, smaller wounds should be repaired in a manner that best recreates lines and inflections that approximate the original subunit configuration. On the other hand, the subunit concept need not and should not be the overriding factor in deciding which local adjacent tissue transfer is utilized for a given wound. For example, the bilobed transposition flap is not a subunit repair, yet, when done artfully, it can provide a highly aesthetic outcome.

Figure 7.4 Nasal subunits as delineated by Gary Burget, MD. Aesthetic nasal reconstruction takes into account the normal boundaries of the nasal subunits

While the following regional approach is meant as a guide for nasal repair, it is important to note that every case requires a thoughtful analysis and no atlas of reconstruction can approximate a given clinical scenario. A flap that works beautifully in a patient with a long thin nose and mobile nonsebaceous skin may be a very poor choice in an operative candidate who has a short nose with thick, sebaceous, nonmobile skin. In the latter case, an adjacent tissue transfer may not even be indicated.

As a final introductory comment, it has been suggested by some highly skilled surgeons that local adjacent tissue transfers on the distal nose have a very limited place in aesthetic nasal reconstruction. In lieu of these repairs, the authors note the superior outcomes of delayed pedicle flap reconstructions with a subunit approach. While we agree that complex distal nasal wounds are reliably repaired with interpolated pedicle flaps, with care many operative wounds of the nose can be beautifully reconstructed with local adjacent tissue transfers, thus saving enormous amounts of time, effort, and monetary expenditure. Most patients would prefer to have a one-staged procedure, and therefore it is important for the dermato-logic surgeon to be solidly versed in these repairs.

NASAL BRIDGE

The nasal bridge is created by the nasal bones and the upper lateral alar cartilages. The skin in this area is usually nonsebaceous. In some individuals, substantial laxity exists, while in others, the integument is draped tautly like a drum. Laxity for the upper nasal bridge is located superiorly in the glabella, while laxity for the lower bridge can be identified on the sidewalls, and in some cases from the nasofacial sulcus. The upper nasal bridge has a natural concavity in most individuals, and this graceful genuflection should be maintained where possible.

Upper Nasal Bridge

Linear repairs

Only relatively small wounds of the upper nasal bridge should be repaired linearly. While tissue laxity may be adequate to close larger wounds without tension, horizontal closure may lead to a horizontal web, and vertical closures may result in standing tissue cones on the glabella and mid bridge. For that reason, the favored repairs are usually adjacent tissue transfers. The glabella often provides a suitable reservoir for such flaps and as the resultant multidirectional tension vectors and broken up scar lines are generally preferred.

Advancement

A historically preferred repair was the single pedicle advancement flap3 (Fig. 7.5). This repair suffers from two design flaws. It recruits little additional laxity from the glabella, and the rectangular flap has the tendency to obliterate the natural concavity of the upper bridge and produce tip elevation. For that reason, this flap is no longer in common use. Similarly, direct island pedicle flaps have been described for this region, but the pedicles for these flaps are relatively immobile, and other repairs are usually preferred.

Figure 7.5 Classic advancement flap of the dorsal nose seen in many texts. This flap is relatively immobile and blunts the natural reflection from the forehead to the nasal bridge. It is best avoided

Rotation

Small glabellar rotation flaps can provide a suitable repair for defects of the nasal bridge, especially those with a horizontal dimension greater than the vertical dimension. The arc of rotation bows vertically on the glabella and allows for closure of the secondary defect in a horizontal direction (Fig. 7.6). The flap will usually rotate into the operative wound under low to no tension. This reconstruction should be elevated above the procerus and fascia to allow for greater tissue movement. In addition, it is important to ensure that the flap is not too thick for the recipient wound.

Figure 7.6 Rotation flaps from the upper nose and glabella can be utilized to repair operative wounds of the nasal bridge. A backcut into the glabella facilitates flap motion. (A) A moderate wound of the nasal bridge. A linear repair is considered, but a rotation flap from the glabella and upper bridge provides more motion. (B) Immediate reconstruction. (C) Repair at one year (Reproduced with permission from Goldman GD. Rotation flaps. In: Rohrer TE, Cook JL, Nguyen TH et al. Flaps and grafts in dermatologic surgery; Saunders Elsevier;Philadelphia. 2008: Fig 5.7. Copyright Elsevier.)

Transposition

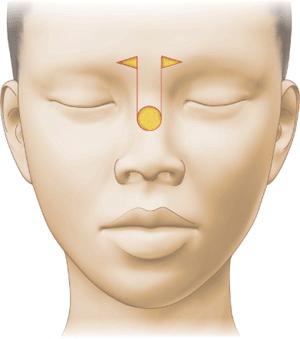

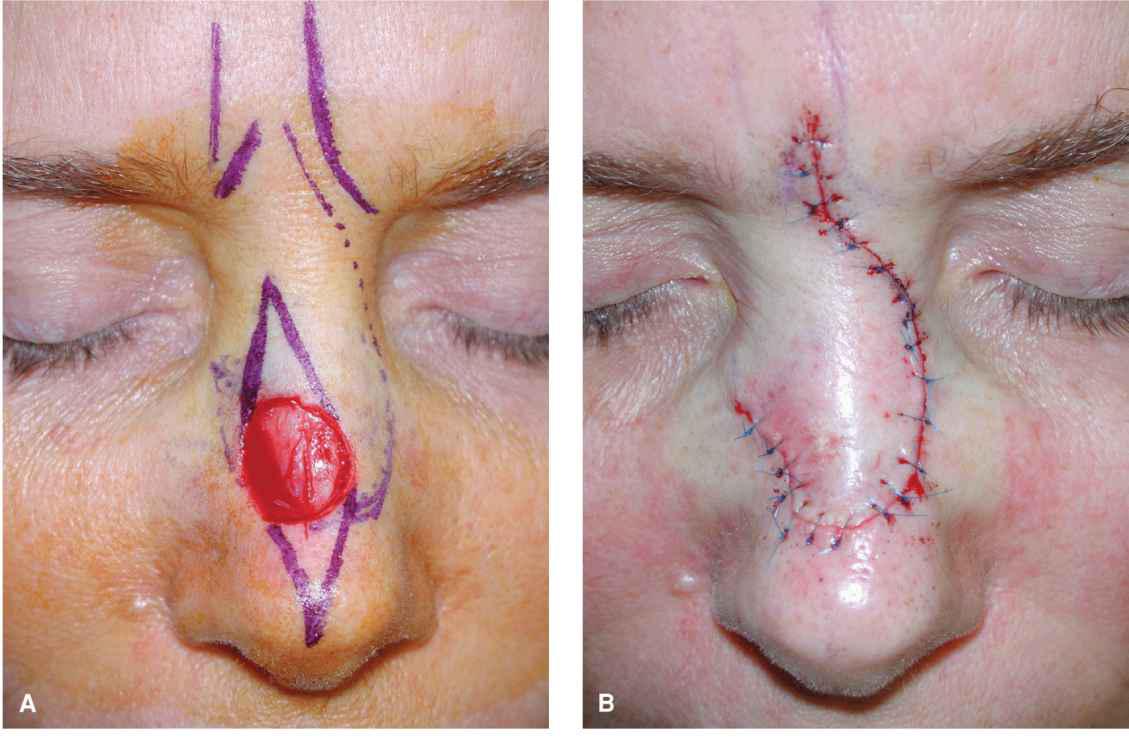

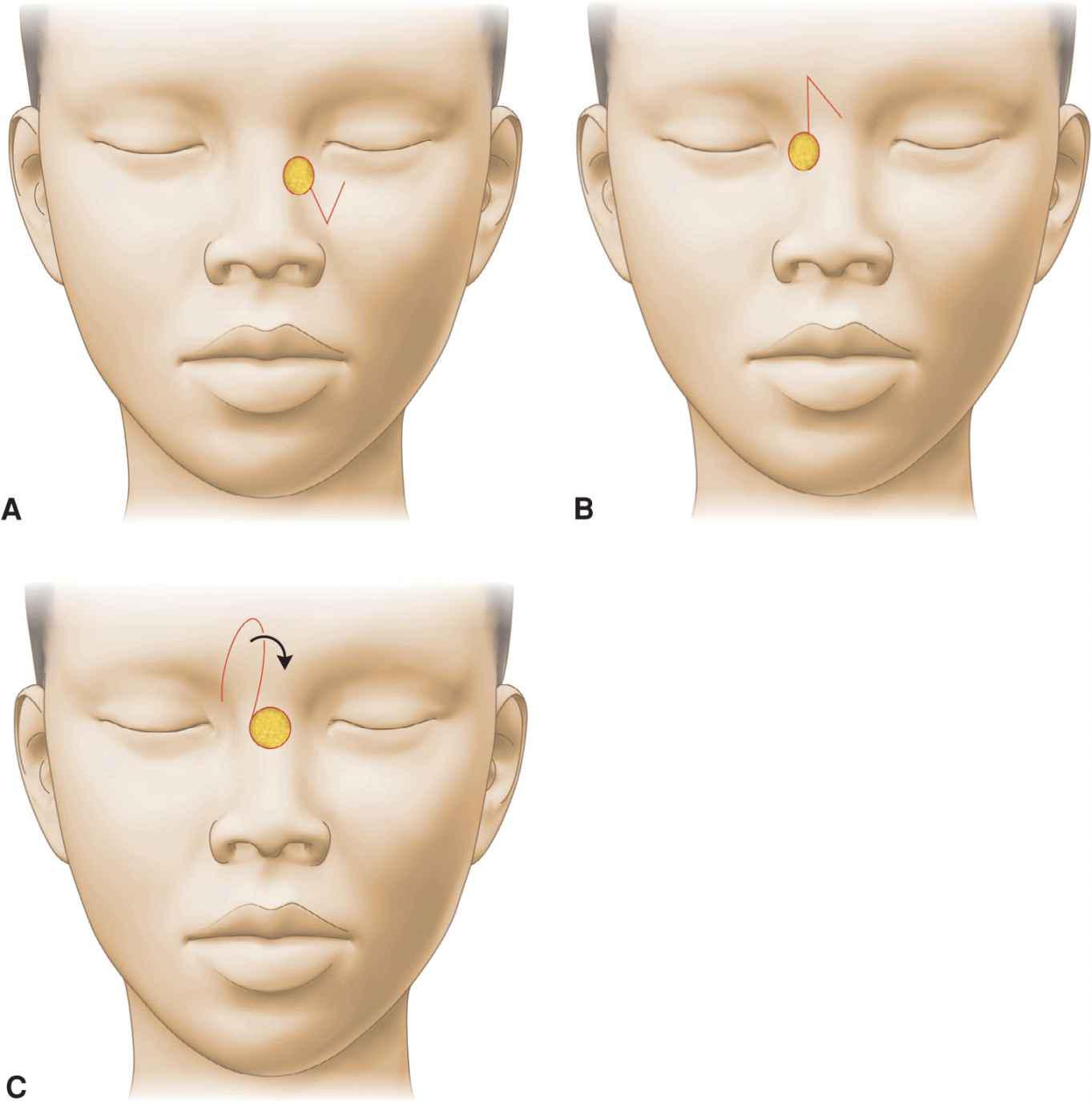

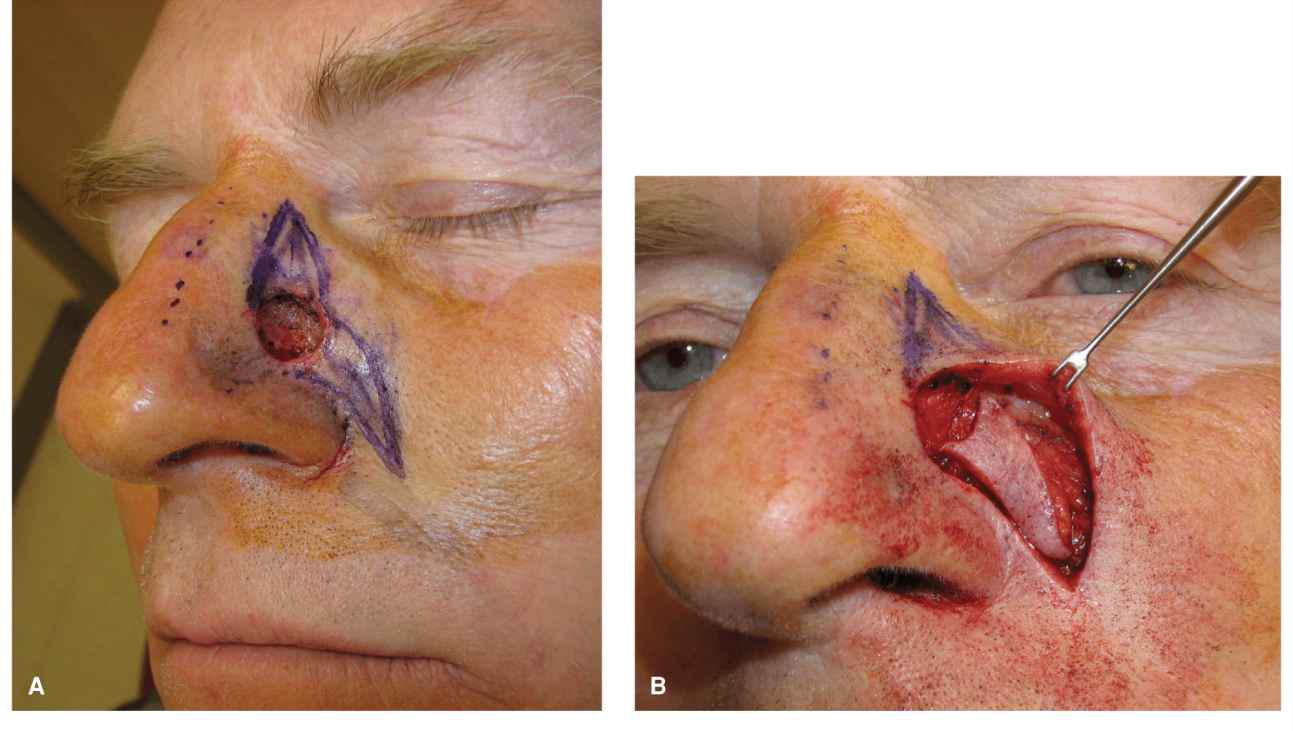

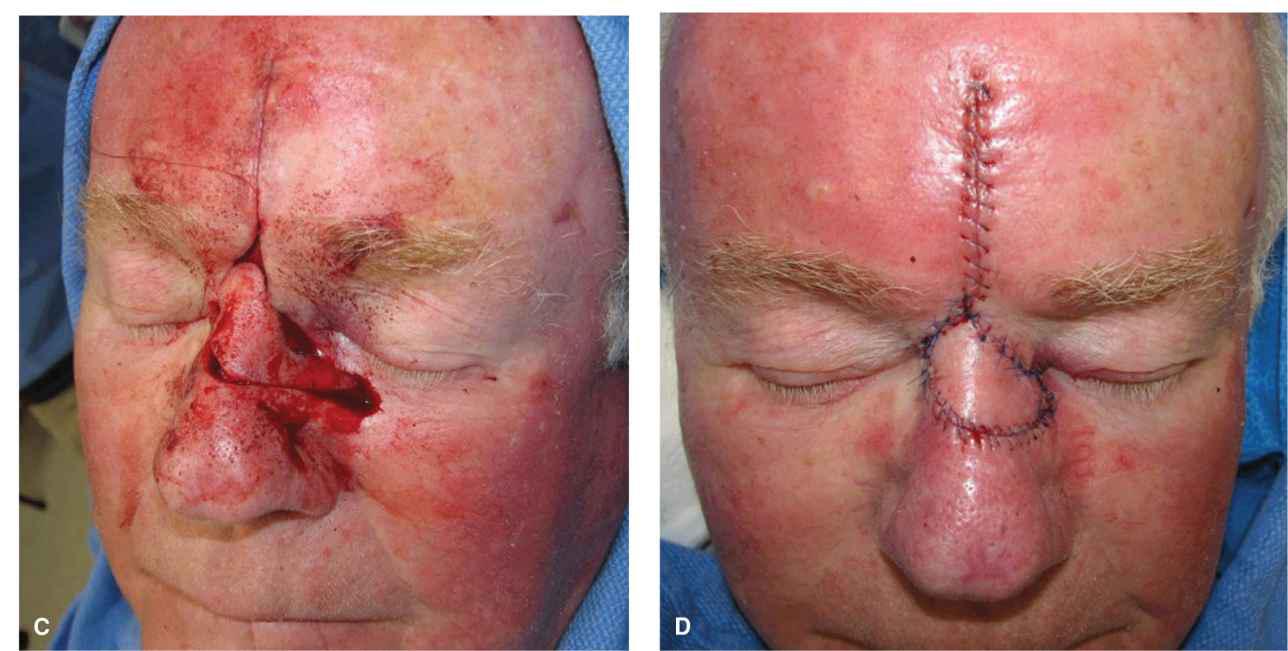

Glabellar transpositions represent a conceptual extension of the glabellar rotation flap. Transposition flaps can be designed such that the secondary defect of the reconstruction creates a vertical glabellar crease, thus blending in as a natural appearing rhytid. In general, these cannot be classic rhomboid flaps, as the basic rhomboid flap will often produce unwanted tensions and tissue redundancy at this three-dimensional location. For that reason, a modified rhomboid or banner transposition is favored4 (Figs. 7.7 and 7.8). For wounds on the lateral bridge, a medially elevated flap is favored, and for more central wounds, a lateral elevation is designed. Substantial wounds of the central or lateral upper bridge can be repaired in this manner, albeit the reservoir of hairless, mobile glabellar tissue varies greatly from patient to patient. A nice feature of this repair is that essentially all tension is placed medially to laterally on the forehead, allowing the flap to drape under no tension into the operative wound. A variation of this repair involves the creation of a mobile island flap, in which the island has a pedicle based on perforators from the supratrochlear artery5 (Fig. 7.9). By severing the dermal attachment toward the base or the flap, while maintaining a deep pedicle, this repair can diminish the formation of a superficial standing tissue cone which sometimes results from a simpler banner flap reconstruction.

Figure 7.7 The upper nasal bridge is usually best repaired with transposition flaps, either rhombic or banner, using adjacent laxity. Linear repairs in this area change the topography of the bridge and can cause bridging and or distortion. (A) The medial cheek often provides laxity for a small rhombic flap. (B) Rhombic flap from the glabella. (C) Somewhat larger wounds may be repaired with a banner flap or a banner island flap from the glabella

Figure 7.8 Defects of the upper lateral nasal bridge are reliably repaired with transposition flaps. (A-C) A banner flap from the glabella takes advantage of glabellar laxity to repair a wound on the nasal bridge. The repair also establishes a junction between the nose and forehead, thus maintaining the natural concave deflection at this point. (D-H) A modified (oversized) rhombic flap is used to repair a wound adjacent to the medial canthus. Follow-up at 1 year is demonstrated (A-H: Reproduced with permission from Cook JL, Goldman GD. Random pattern cutaneous flaps. In: Robinson JK, Hanke CW, Siegel DM, et al. (eds). Surgery of the Skin. Copyright Mosby Elsevier; Edinburgh. 2010.)

Figure 7.9 A sizeable wound of the upper lateral nasal bridge is repaired with a rotated and transposed island flap. The original flap design is similar to that in Figure 7.7A, but the flap is elevated as an island and then rotated and transposed into place. (A) Large operative wound of the upper nasal bridge. (B) An island flap is incised on the glabella. (C) The flap is elevated, rotated, and transposed into place. (D) Immediate reconstruction. (E) Repair at one year (Photos courtesy of Todd Holmes, MD.)

Nasal Bridge—Mid and Lower

Linear

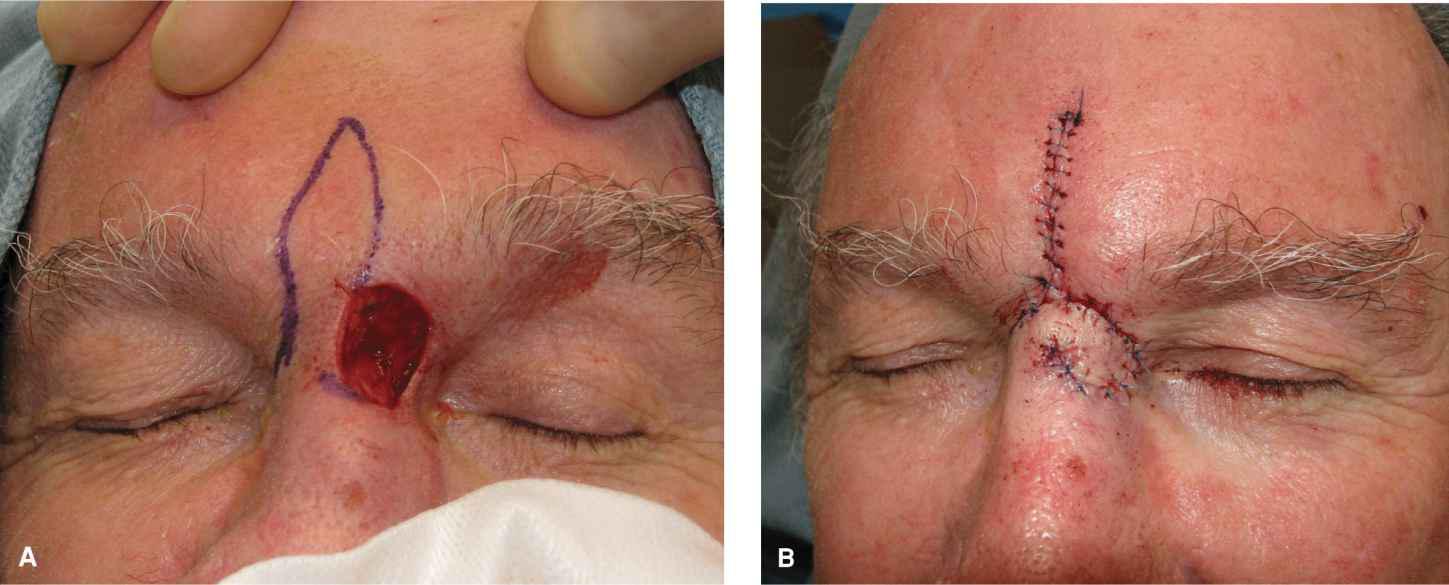

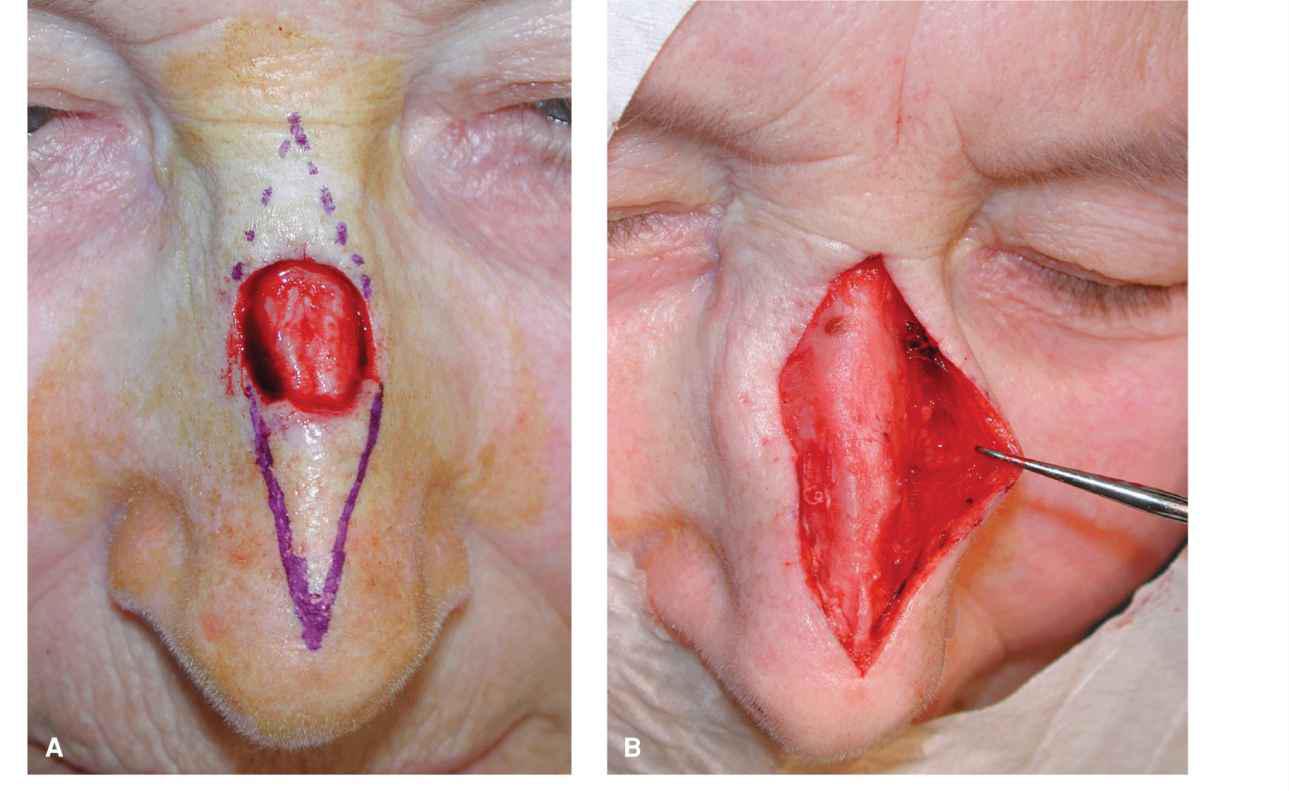

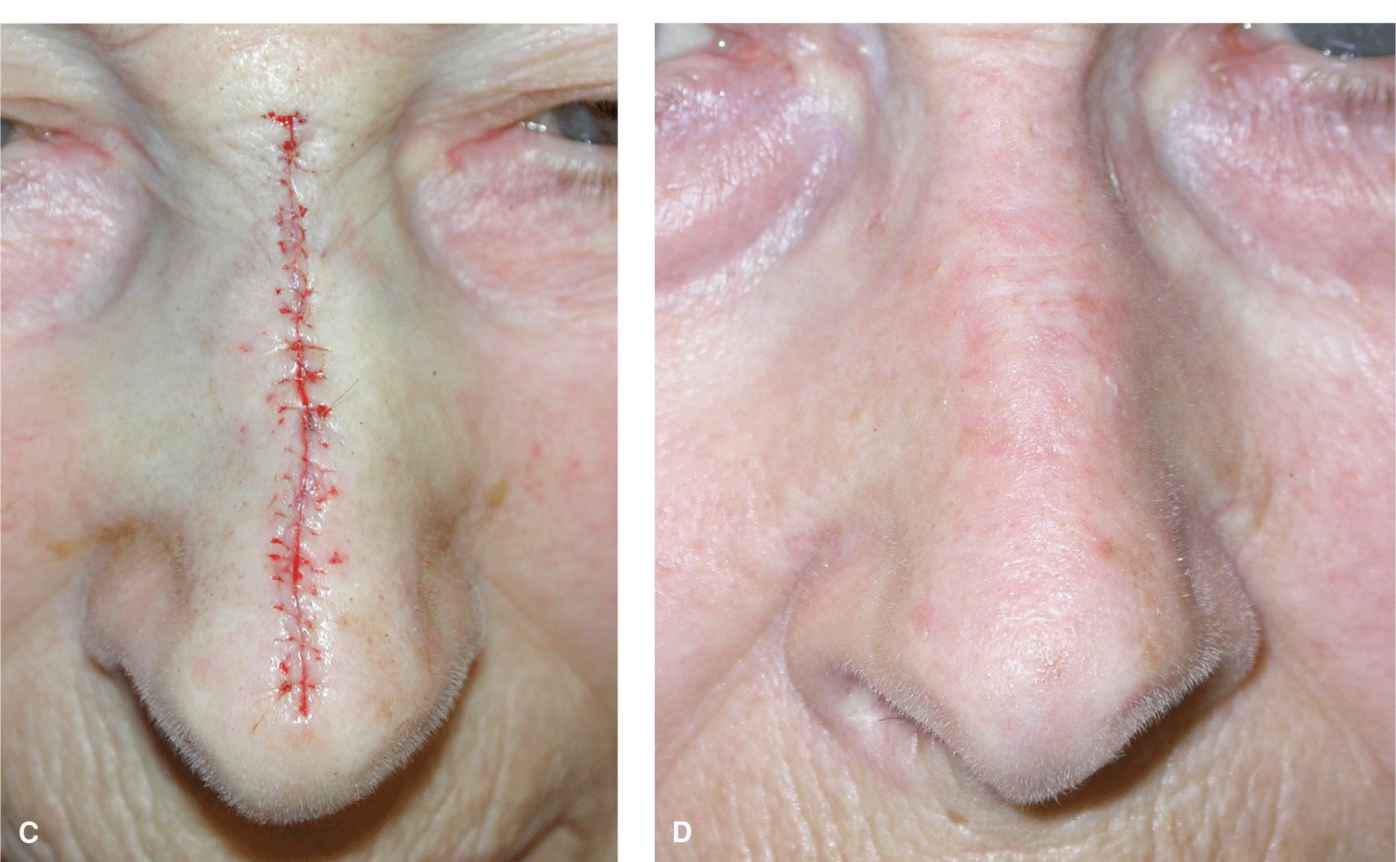

In distinction to defects of the upper bridge, small-to-moderate defects of the lower nasal bridge can be suitably repaired with a vertical linear reconstruction. Such wounds are generally less than 1.0 cm in diameter, but can occasionally be larger in patients with longer straight noses. Because of the normal convexity of the nose, it is imperative that such repairs have an adequate vertical dimension. A length-to-width ratio of 4:1 or 5:1 prevents accentuation of the dorsal nasal hump and diminishes the formation of standing tissue cones6 (Fig. 7.10). Except for the smallest defects, this repair should be accomplished by elevation at the level of the deep fascia underlying the nasal musculature. Wide undermining may be needed, and in some cases, the attachment of the fascia to the nasofacial sulcus may be lysed in order to achieve additional mobility. When achieving this last step, it is imperative to remain just above the periosteum in order to pass under the distal extent of the angular artery.

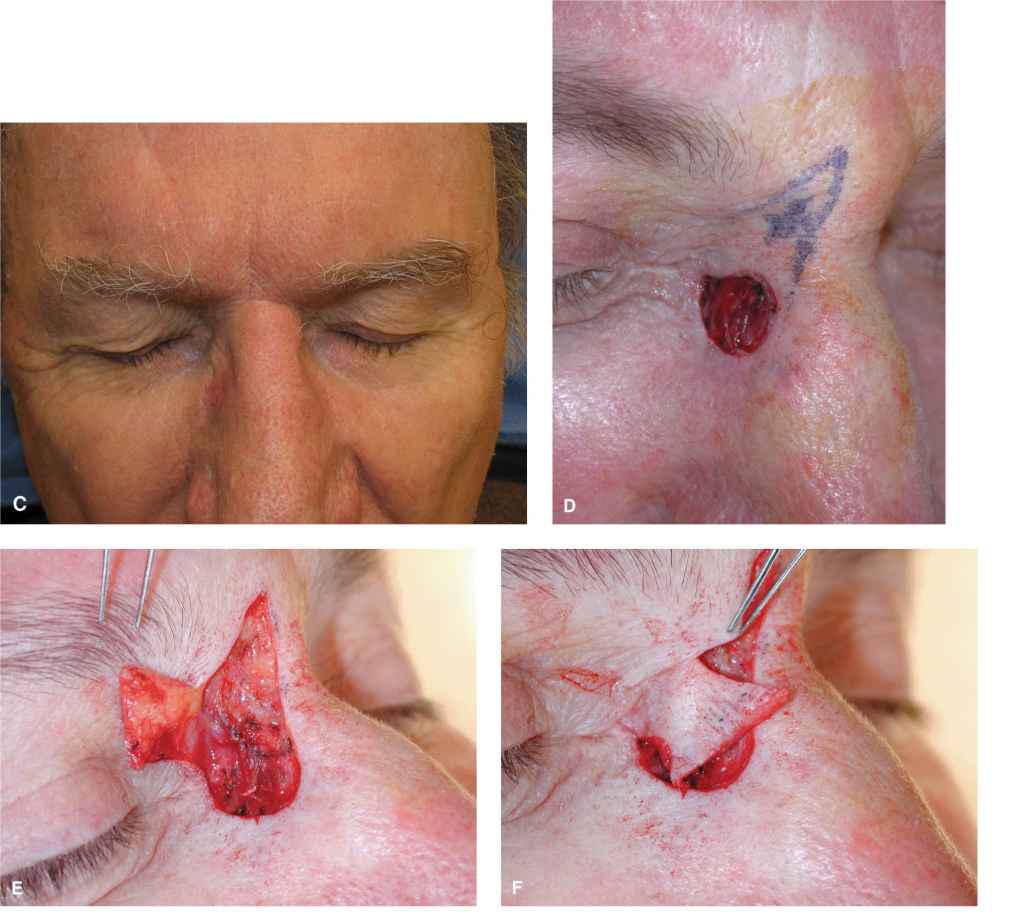

Figure 7.10 Complex linear repair for a wound of the nasal bridge. A length-to-width ratio of 4:1 or 5:1 is often preferable to prevent nasal hump accentuation and dog-ear formation. Such repairs are best elevated at the perichondrium and periosteum, and undermining out to the nasofacial sulcus may be necessary. (A) Operative wound and long repair design. (B) The repair is incised and the edges are undermined at a periosteal plane out to the nasofacial sulcus. (C) Immediate repair. (D) Reconstruction at one month

Nasal Sidewall

Defects of the nasal sidewall are common, and the mobile skin of the sidewall and medial cheeks afford a multitude of reconstructive options.

Linear repairs

Smaller wounds of the upper and mid nasal sidewall are suitably repaired in a linear fashion. Most of the literature demonstrates linear closures that conform to an axis based on a radial spoke with an origin at the medial can-thus. In practice, this is often useful for modest wounds of the upper sidewall. On the other hand, many sidewall defects, especially those further down the nose, are better repaired with linear closures with their apex at the mid upper bridge and with an inferolateral slant. In each case, the surgeon should do a manual exam in order to determine where laxity exists and orient the repair in the manner that optimizes tissue laxity and creates the least tension on the medial canthus, nasal tip, and/or nasal ala.

Advancement

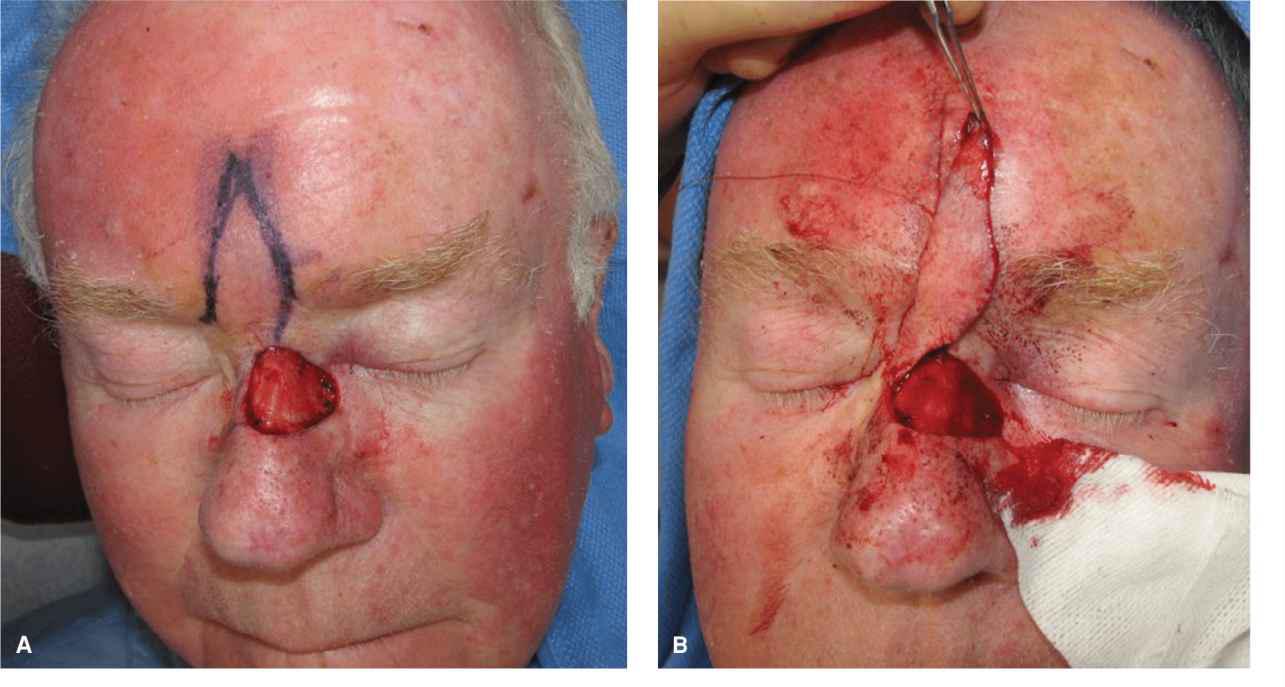

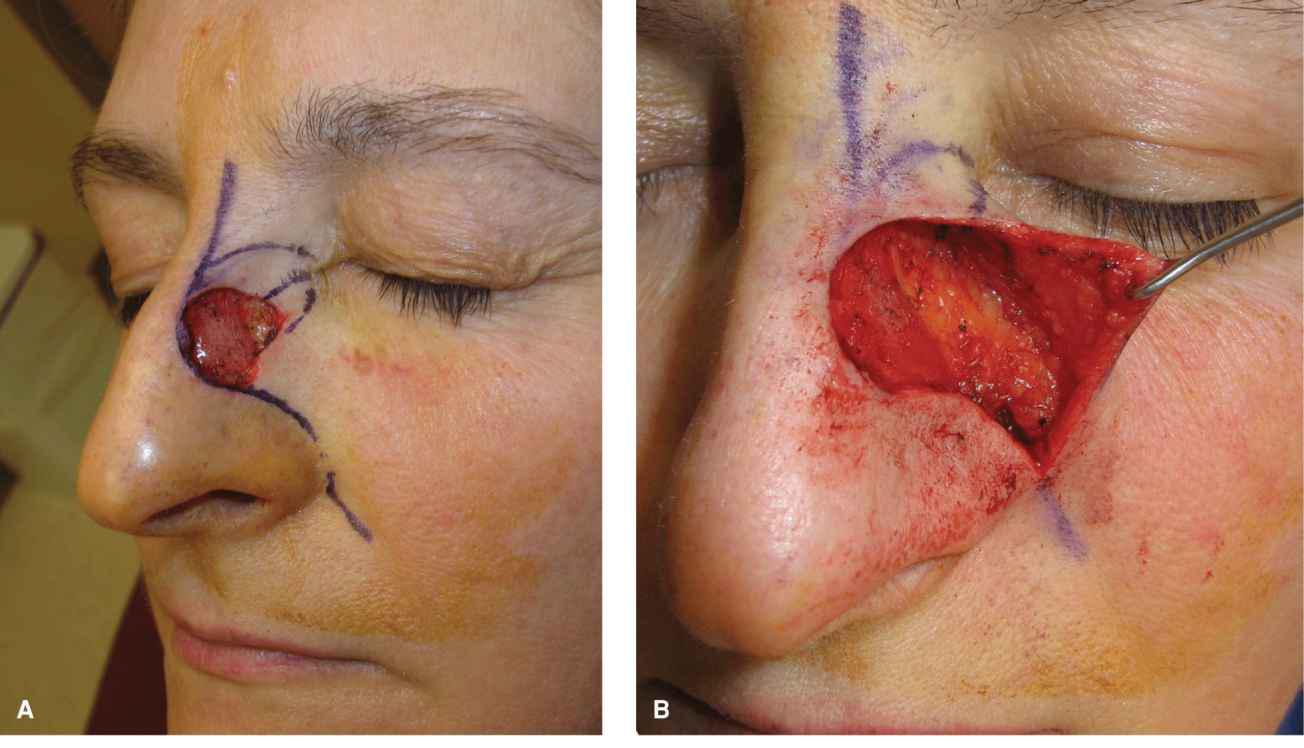

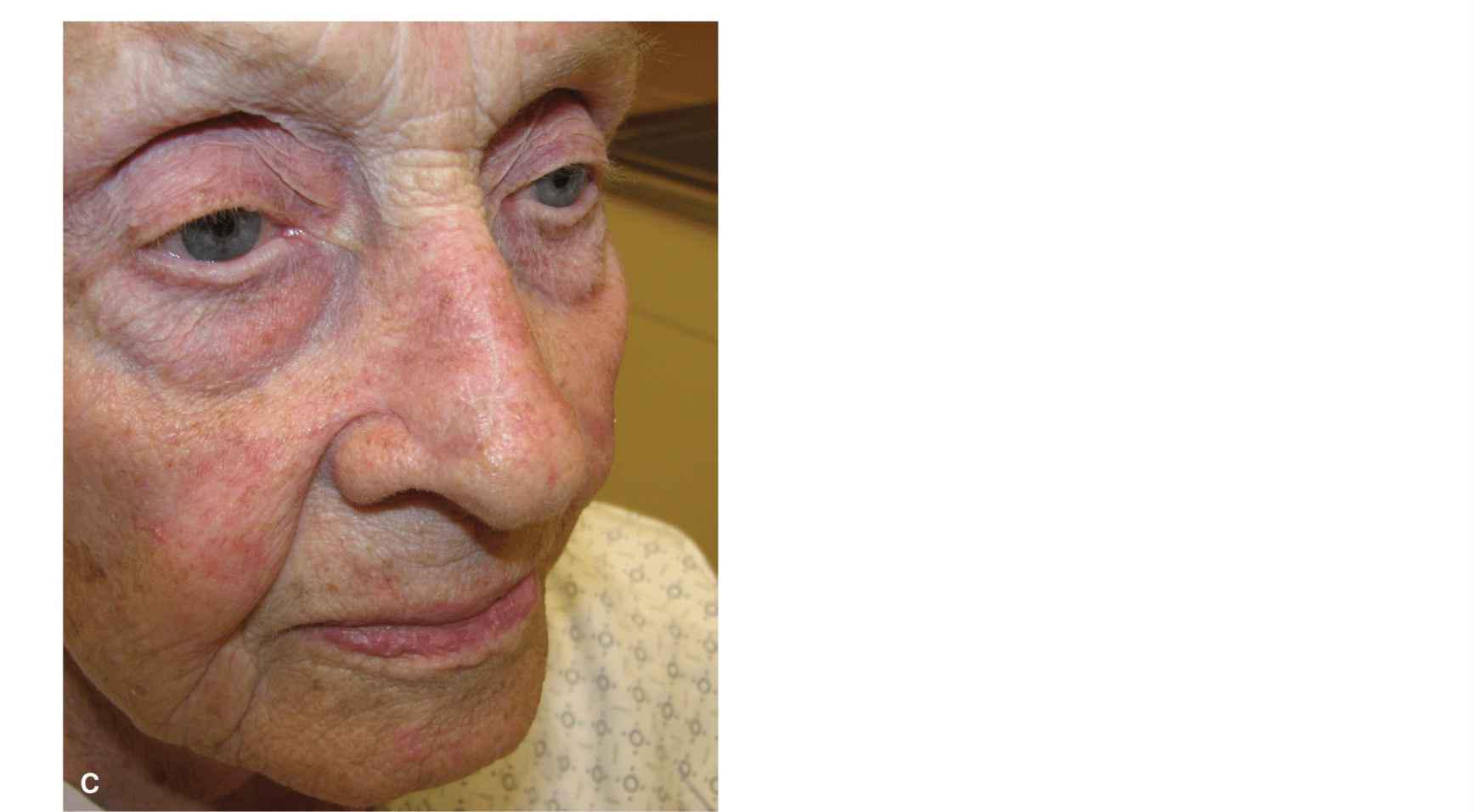

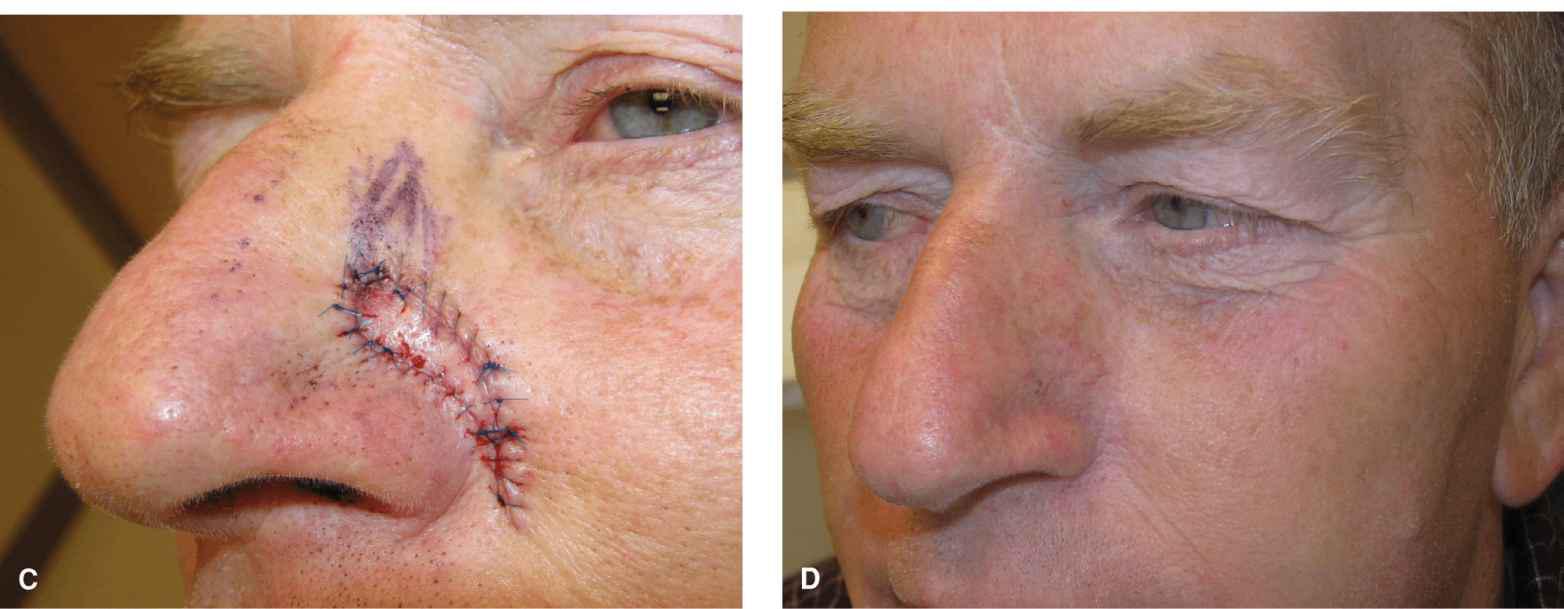

Moderate-to-large operative wounds of the sidewall may be repaired with cheek laxity. Advancement flaps allow for closure of wounds with excellent aesthetics, often placing repair line parallel to or within normal skin lines7,8 (Fig. 7.11). Such repairs usually place incision lines within or adjacent to the nasofacial sulcus. The superior redundant tissue cone is usually removed vertically, but sometimes it is angled toward the medial can-thus. The inferior tissue redundancy is managed by extending incisions around the nasal ala and, as needed, down the nasolabial fold. The flap is elevated in the deeper subcutaneous plane, but above the nasal musculature. Undermining may not need to be extensive, as substantial tissue laxity often allows for facile closure even of larger wounds. It is imperative to remove an adequate displaced standing tissue cone or crescent of tissue in order to maintain the position of the lateral ala and nasolabial fold (Fig. 7.12).

Figure 7.11 A crescentic cheek-to-nose advancement flap. The flap is elevated above nasalis and advanced from cheek to nose. The flap must be of adequate length to avoid bridging or tenting the nasofacial sulcus. The tissue redundancy created by advancing the upper portion of the flap is excised as a crescent around the alar crease. (A) Operative wound of the nasal sidewall and planned advancement. (B) An advancement is elevated on the cheek. (C) The repair is advanced and sewn into place, using a crescentic approach inferiorly. (D) Reconstruction at six months

Figure 7.12 In older patients, a lax cheek can be utilized to repair large nasal operative wounds. In this case, the flap was used to resurface the majority of the broad nasal operative wound, and the crescentic dog-ear was used as a full-thickness skin graft to cover the remaining wound. This repair would not be feasible in a younger patient with less tissue redundancy

Rotation

Smaller wounds of the lower nasal sidewall can be repaired with relatively small rotation flaps.9 The typical wound for this type of repair is a modest defect of the lower medial nasal sidewall just above the medial alar crease (Fig. 7.13). Such repairs are based on a lateral pedicle and are elevated above nasalis. Tension is medial to lateral and is shared by the upper nose and medial cheek. The lower margin of the flap can often be tucked into the alar crease.

Figure 7.13 A small rotation flap is utilized to repair a wound just above the alar crease. The flap is elevated above nasalis and has extensive mobility. (A) Deep sidewall defect and planned reconstruction. (B) The flap is elevated above muscle and rotated into place. (C) Side view at one month. (D) Anterior view at one month

Island

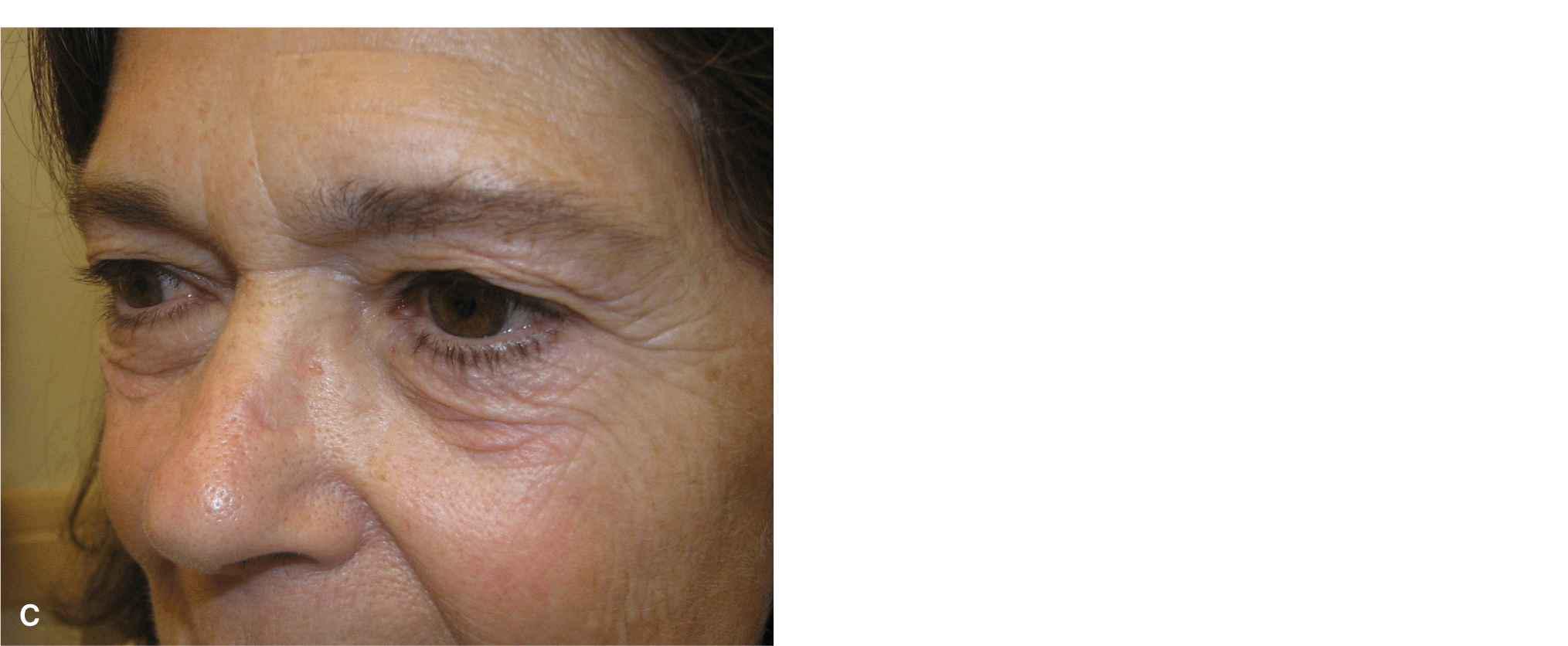

Island flaps are niche repairs for defects of the lateral nasal sidewall which do not lend themselves to closure by advancement. The advantage of an island flap in this region is that it can often be a more limited repair from a standpoint of area. Defects of the upper lateral nasal wall can be repaired with laterally based subcutaneous pedicles. After separating the depth of the flap from the underlying levator labii, the flap moves with great ease and swings into position with minimal tension. The disadvantage of any island flap is the tendency to trapdoor, albeit this usually resolves within 1 year. Another disadvantage is that the scar, if visible, has an unnatural triangular contour.

Defects of the lower lateral sidewall can be readily repaired with an island flap in which the island curves around the lateral ala (Fig. 7.14). Such flaps must be carefully freed from underlying pivotal restraint, and the base of the flap in this case contains many perforators from the levator labii and/or nasalis. It is imperative in this case to substantially undermine the leading edge of the flap, to free the lagging restraint, and to suture the flap into place at a slightly recessed level. All three of these technical issues minimize the pincushioning of such reconstructions in the months following repair.

Figure 7.14 A small island flap is used to repair a wound of the upper ala. In this case, the pedicle has a simple, deep base with multiple arterial perforators. The repair hides nicely in the alar crease

Transposition

Small and moderate defects of the nasal sidewall are amenable to repair with modified rhomboid transposition flaps (Fig. 7.15). While simpler repairs such as a direct closure should be considered first, a transposition flap can readily recruit laxity from the cheek and redirect tension vectors. This can be particularly valuable when the sidewall skin is tight and immobile, but the adjacent upper nasal or cheek skin is loose and mobile. Flap elevation is done in the subcutaneous plane above the nasalis. An advantage of a transposition over an advancement is a shorter, more geometrically broken up scar, but a disadvantage can be the tendency to pincushion and to form a small web at the nasofacial sulcus.

Figure 7.15 Moderate wounds of the upper lateral sidewall and/or bridge are amenable to closure with relatively small rhombic transposition flaps. Ample laxity is usually found on the upper lateral nasal bridge or adjacent cheek. (A) Defect and planned reconstruction. (B) Immediate closure. (C) Result at 6 months

Nasal Tip

The nasal tip is one of the more challenging areas facing the reconstructive surgeon. Even small topographical deflections and surgical scars are readily visible at a conversational distance. The skin of the tip of the nose can vary widely. In some individuals, this area is tight, thin, and tightly draped over prominent lower lateral alar cartilages. In other individuals, the tip is thick, rubbery, and highly sebaceous. Essentially, all repairs of the nasal tip should be performed just above perichondrium. Sutures should be placed more deeply in this region to avoid spitting sutures.

Linear

Diminutive wounds of the midline nasal tip can be closed with a vertical linear repair. It is important, just as with a nasal bridge repair, that the repair be long enough to avoid the formation of a dorsal nasal hump.

Advancement

A common wound on the distal nose or tip is a modest defect just to one side of the midline and above and medial to the soft triangle. Such wounds are often repaired with a transposition flap, but if the wound is relatively distal, and if the tip and columella are adequately broad, a suitable reconstruction is a modified burrows advancement flap10,11 (Fig. 7.16). In this repair, a standing tissue cone is removed vertically, and the inferior standing tissue cone removal is displaced at the midline. This repair can only be utilized for defects of the supratip, and care must be taken to ensure that the ipsilateral nostril is not flared by the lateral tension placed on it.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree