Chapter 3 Non-surgical Facial Rejuventation with Fillers

Summary

Soft Tissue Loss in the Aging Patient

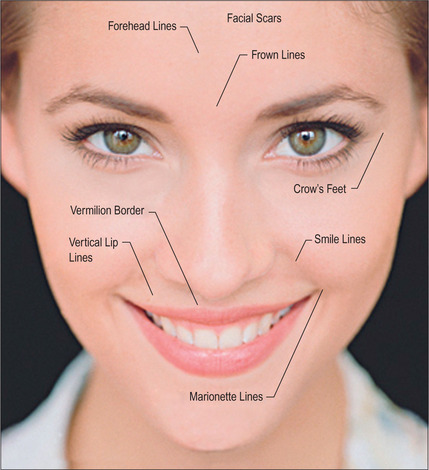

Some of the features that a youthful face exhibits include smooth contours, few wrinkles, except in dynamic expression, and full subcutaneous tissues with minimal or no soft-tissue atrophy (Fig. 3.1). Nasolabial, glabellar and crow’s feet skin folds are almost uniformly absent at rest, and minimally noticeable, even with muscular contraction. During aging of the normal, healthy adult, there is loss of soft-tissue fullness in the face, often beginning in the nasolabial folds and progressing inferiorly along the marionette lines. Lines in the upper face may show years earlier during dynamic expression than at rest. Lipoatrophy can distress the aging patient with resultant low self-image and self-esteem, depression and social isolation.1,2 With the severe rise in obesity in recent years, loss of facial fat due to aging may be partially offset due to fatty accumulation after weight gain.

In the normal aging face there is gravitational pull on sagging skin, flattening of the youthful contours, accompanied by solar degeneration, variation in pigmentation, an increase in rhytids, capillary break-down, loss of muscle tonicity and progressive thinning of the skin and subcutaneous tissues (Figs 3.2 and 3.3). One of the hallmarks of aging skin – and one for which we have essentially no topical or minimally invasive corrective solution – is poor elasticity, breakdown of elastic fibers and excess skin envelope. In essence, with an imbalance of soft tissue volume to skin envelope, there are three basic approaches: 1) fill up the lost tissue volume, 2) chemically peel, laser, or mechanical dermabrade or excise the excess skin, or 3) live with the difference. Because few patients have one isolated contributing factor, the ideal approach would often include volume restoration and treating the skin. However, many patients do not desire more aggressive treatment. Chemical peels and lasers chemically denude the superficial layers of the skin, but do not reduce the surface area of the skin sufficiently to balance the loss of soft tissue volume in any but the mildest conditions in the youngest patients. While they tighten the skin, in essence by cross-linking collagen and other proteins, they do not restore the elasticity of youth.

Soft Tissue Loss in Disease Conditions

While less common, certain disease conditions cause premature loss of soft-tissue volume; some are genetic and some acquired. Congenital generalized lipodystrophy (autosomally recessive) results in lack of adipose tissue from birth. Familial partial lipodystrophy (autosomally dominant) causes progressive peripheral fat loss beginning at puberty and, typically, the facial fatty tissue will stay the same, or rarely gain fat, while the body atrophies. Mandibulosacral dysplasia (autosomally recessive) shows two forms: type A demonstrates peripheral fat loss with normal or excess facial fat, while type B shows generalized fat loss. Partial lipodystrophy (autoimmune mediated) presents during childhood or adolescence and the upper body, including the face, presents with fat loss. Excess fat is found in the legs and hips. Generalized lipodystrophy (immune mediated) presents during childhood or adolescence and shows generalized fat loss, including the face.

Acquired lipodystrophies arise from multiple mechanisms, but more commonly small localized areas of fat loss may occur from drug injections, local trauma or crush injuries, immune-mediated mechanisms, cancer or HIV, the most prevalent form. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is associated with the condition, but its actual mechanism is unknown. There appears to be some interaction with protease inhibitors and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The HIV patient shows rapid loss of peripheral fat and fat in the face, occurring within 1 year of treatment.3 Fat paradoxically accumulates in the abdomen, breast and dorsocervical spine. In the face, the buccal and temporal fat pads are most locally affected; however, there is loss of fat diffusely in the face. Fat loss may be rapid and progressive and is often permanent, refractory to steroid administration and dietary intervention. The prevalence has been reported as variable (18-83%) due to differing definitions.4 Lipoatrophy in HIV patients can lead to compliance issues, reducing the effect of HAART and accelerating disease progression, fear of stigmatization and recognition.5,6

Indications

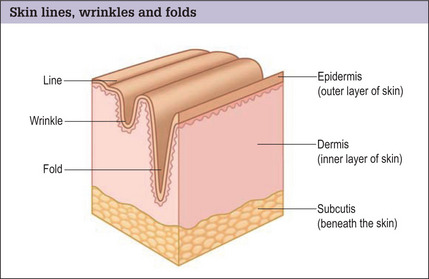

Skin lines, wrinkles and folds

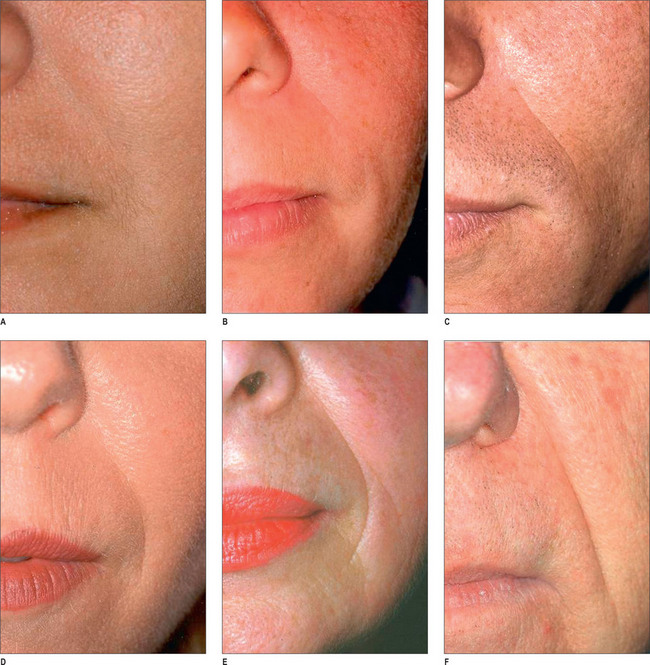

By far the most frequently injected area, the nasolabial fold (NL), may be best evaluated by the standardized Lemperle scale of severity (Fig. 3.4). Natural folds in the face are created by attachment of the facial muscles to the undersurface of the skin. No comparable scale is widely used in the marionette lines, the crow’s feet and/or other skin folds of the face. However, an appropriate approach would be to use the commonly accepted Lemperle scale. The NL fold may begin to appear in the early 20s and progresses with aging. While this scale is primarily focused on skin wrinkling, soft tissue loss is a contributing factor as well.

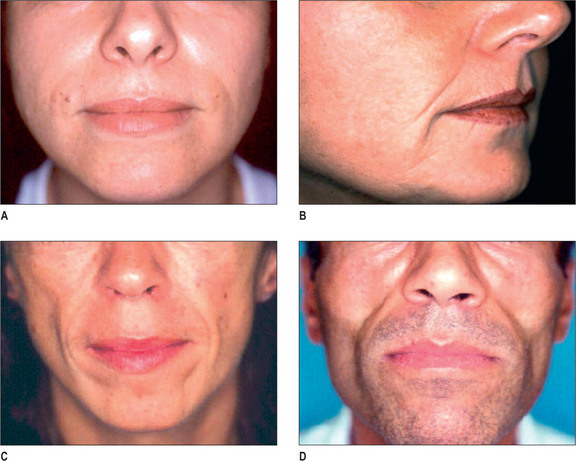

Facial lipoatrophy scale

A four-point grading system is commonly used to measure facial lipoatrophy (Fig. 3.5). Grade 1 is characterized by small localized areas of fat loss, especially in the nasolabial folds. Grade 2 includes mentolabial folds (marionette lines) and may include concavity of the lips. Grade 3 progresses to malar fat atrophy, preauricular hollowing and shadowing of the cheeks and mandibular ridge, while Grade 4 demonstrates malar fat ptosis, temporal hollowing and protruding musculature and bones.

Preoperative History and Considerations

Pre-procedure analysis

Age is an important factor, as approximately 80% of all injections are performed between the ages of 35 and 64.7 Increasing age leads to the tendency of decreased immunogenicity, so, presumably, there would be less of an inflammatory response to a permanent or semi-permanent filler. However, thinner skin and dermal atrophy make superficial injection techniques risky, as lumpiness and color deformity may occur more readily. Avoidance of aspirin, NSAIDs, gingko biloba, St. John’s Wort, and high-dose vitamin E for 1-3 weeks prior to the injection is encouraged.

Injectable Fillers

We have truly entered the ‘filler revolution’ and the number of new fillers on the market is constantly increasing.8 The first injectable filler that was approved by the FDA was bovine collagen (Zyderm/Zyplast; Inamed Aesthetics, Santa Barbara, CA). The need for skin testing and its lack of longevity were key issues hindering its widespread use.9 Since this time, many classes of fillers have been approved by the FDA, with more likely in the future. Listed in this section is a brief description of each of the major injectable fillers currently being utilized in the USA.

Hyaluronic acid

Of the 9.2 million non-surgical cosmetic procedures performed in 2004, almost 900 000 included augmentation using injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers.10 Hyaluronic acid is a glycosaminoglycan that is a naturally occurring polysaccharide. Hyaluronic acid is an essential component of the extracellular matrix, essentially ubiquitous throughout all animal species. Therefore, it has no species or tissue specificity, making HA ideal from an immunologic standpoint. In its native form, catabolism of HA is rapid (hours to days), therefore stabilization via crosslinking is essential for utility as an injectable filler. HA is hydrophilic and able to retain 95% of volume with water.11 Unique to HA is its ability to follow isovolemic degradation, a process by which the remaining molecules of HA are able to bind an increasing amount of water thus maintaining volume until the majority of product is degraded.

Currently, there are several HA derivative products approved by the FDA. All products are approved for mid-to-deep dermal implantation for correction of moderate-to-severe facial wrinkles and folds:12–14 Restylane (Medicis, Scottsdale, AZ), Perlane (Medicis, Scottsdale, AZ), Juvederm (Allergan, Irvine CA), Captique (Allergan, Irvine, CA), and Hyalform (Allergan, Irvine, CA). Restylane was the first of the HA fillers to be FDA approved (12/2003); in initial studies by Narins et al it showed superiority to Zyplast with a smaller concentration of product.15 Restylane has a HA concentration of 20 mg/ml, a gel particle size of 400 μm, and a 1% degree of crosslinking.16 It is distributed in 0.4 ml and 1.0 ml disposable syringes. Wang et al17 recently reported that, in addition to the physiochemical properties of Restylane, it may augment dermal filling by stretching fibroblasts and thereby stimulating de novo collagen formation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree