CHAPTER 55 Neurovascular Injury

Total hip arthroplasty has become a predictable operation with few complications and excellent long-term results. Among the most serious complications are peripheral nerve injuries. These infrequent complications occur in 0.08% to 7.6% of total hip replacements and are more common in revision hip surgeries.1–29 Schmalzried and colleagues reported a 3.2% prevalence in revision hip surgery, whereas earlier reports noted a higher percent.21,30,31

ANATOMY

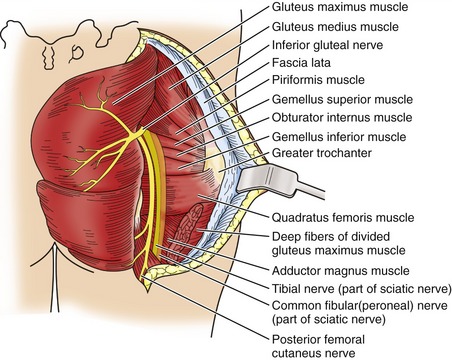

The sciatic nerve is the most common nerve injured during hip surgery, accounting for 79% of all peripheral nerve injuries.30,32 Isolated femoral nerve injury is less common, accounting for 13% of injuries, and obturator nerve injuries are the least common (1.6%). The predominance of sciatic nerve injuries has been a source of great interest and may be best explained by the nerve’s anatomic location and peculiarities. The sciatic nerve is composed of roots from L4 to L5 and the anterior division of the first three sacral nerve roots. The sciatic trunk is normally 15 to 20 mm across and has a relatively flat band that exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch. It is below the piriformis at this point and continues above the muscle belly of the superior gemelli. In 10% of cases, the tibial and common peroneal nerves are two distinct divisions and are separated by the piriformis. In either situation the nerve continues over the remaining external rotators and is beneath the gluteus maximus. The nerve runs slightly laterally around the ischial tuberosity and provides branches to the obturator quadratus femoris, the obturator internus gemelli group of muscles, and the adductor magnus. The nerve continues from this point into the thigh.33

PERIPHERAL NERVE INJURIES ASSOCIATED WITH TOTAL HIP ARTHROPLASTY

It is well documented that the common peroneal division is injured more often than the tibial division. Furthermore, when it is injured, the damage is greater, with less likelihood for recovery. The most widely accepted explanation for the more frequent and severe injuries to the common peroneal division has been proposed by Sunderland.33 His anatomic study found that the common peroneal division contains a higher percentage of nerve tissue versus connective tissue than does the tibial division. The common peroneal division also contains fewer but larger bundles of nerve or funiculi. Therefore the more tightly bound and larger bundles of the common peroneal nerve make it more susceptible to mechanical injury than the smaller and less bound funiculi of the tibial division (Fig. 55-1).34

FIGURE 55-1 Sciatic nerve anatomy.

(Redrawn from Sunderland S: The sciatic nerve and its tibial and common peroneal divisions: Anatomical and physiological features. In Sunderland S (ed): Nerves and Nerve Injuries. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1978, pp 925-966.)

The femoral nerve is the second most commonly injured. The femoral nerve is well protected in the psoas and iliacus muscles in the pelvis and also as it exits the pelvis below the inguinal ligament. After exiting the pelvis, the femoral nerve divides into two terminal branches. In the femoral triangle the nerve lies lateral to the femoral artery, and approximately 4 cm distal it divides into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior division is short and divides into one motor and two sensory branches. The posterior division divides into the saphenous branch and the motor branch. The saphenous branch travels through the thigh with the infrapatellar branch terminating at the knee. The saphenous branch continues distally, becoming two branches, one to each ankle and foot. The motor branch of the femoral nerve innervates the quadriceps, hip, and knee joints.35 The obturator nerve is found in the substance of the psoas major muscle and crosses the pelvic brim to reach the obturator foramen. As it traverses the pelvis, it is on the obturator internus during the first part of its course but anteriorly may be in contact with the adjacent pelvis before entering the obturator foramen. After exiting the obturator foramen, the nerve branches into anterior and posterior divisions supplying innervation to the adductor musculature, gracilis (anterior division), pectineus (anterior division), and obturator externus (posterior division). The anterior division continues to the subsartorial plexus and the posterior division as an articular branch to supply the knee joint.36

ETIOLOGY OF PERIPHERAL NERVE INJURIES IN TOTAL HIP ARTHROPLASTY

Injury to the nerves around the hip can be caused by one of several mechanisms. The complication of nerve injury is grouped into the major categories of traction or stretch, direct trauma, and compression or ischemia. It is important that the cause of the nerve injury be determined so appropriate action when indicated can be taken in an attempt to improve long-term function of the limb.1,21,30,37 The categorizing of nerve injuries is ideal, but surgeons may not be able to identify the cause of injury in a large percentage of their patients.32,38

Weber and colleagues prospectively studied 30 total hip arthroplasties in 28 patients. Electromyograms were performed 24 hours before and 18 to 28 days after surgery.26 After the surgical procedure in 21 of the hip arthroplasties (70%), there was electromyographic evidence of involvement, whereas in the remaining nine there was no evidence of electromyographic abnormalities. None of the patients had complaints consistent with nerve injury, although in two patients, mild muscle weakness was detected on examination. Although Weber’s study was done when total hip arthroplasty was still a relatively new surgery, the study nevertheless highlights the susceptibility to injury of the nerves around the hip during total hip arthroplasty. The prevalence of electromyographic changes without significant clinical findings is also important and suggests that the injuries are much more common than those that are reported.

The risk factors for nerve injury include congenital hip surgery, revision or previous surgery, female gender, and lengthening of the limb more than 4 cm or more than 6% of the limb’s length.9,19,26 Patients with congenital hip disease who have undergone total hip arthroplasty have been reported to have a nerve injury ranging from 5.2% to 13%.11,21,39 This group of patients possesses two significant risk factors for a higher risk for injury. First, they are more commonly female, and second, their legs are normally lengthened during the procedure. A third potential risk factor is the abnormal anatomy of the hip in these patients, which contributes to a high prevalence of injury, although this is difficult to measure.37

Limb lengthening is a second significant risk factor, and how much a limb can be lengthened is unknown. Farrell and colleagues reported on their experience with motor nerve palsy after primary total hip arthroplasty.40 In their patients in whom a nerve palsy developed, the limb was lengthened an average of 1.7 cm (−0.1 to 4.4 cm). This group was compared with a cohort of patients matched for age, gender, diagnosis, approach, and year of surgery in whom a nerve palsy did not occur after total hip arthroplasty despite lengthening of the limb an average of 1.1 cm (−0.2 to 3.7 cm).40

It does seem reasonable that if a limb has been lengthened and the patient is noted in the recovery room or on the floor early after the surgery to have a nerve injury (femoral or sciatic), then exchanging a modular head to a shorter modular head may improve the outcome. This has been reported,40,41 and each patient must be carefully studied to determine if this possible benefit warrants an additional operation that can potentially lead to soft-tissue laxity and hip instability.*

A third cause of nerve injury is direct trauma. Nerve injury may occur during the surgical approach to the joint, during retractor placement, from surgical devices used to secure implants, or via any other method that can damage the nerve.† Smith and colleagues47 reported contralateral lower extremity nerve injuries in patients undergoing hip surgery in the lateral decubitus position. It is controversial whether the surgical approach is associated with a particular nerve injury. For example, in the anterior approach to the hip, the use of retractors placed anteriorly may increase the risk of femoral nerve injury, whereas the posterior approach may be associated with sciatic nerve injuries.21,22 An additional source of direct nerve injury may involve the contralateral extremity. Smith and colleagues reported six patients with contralateral limb complications, and in five of the six the complication was transient paresthesia. They proposed that the cause of the complications was related to underlying or preexisting vascular disease or obesity and that the lateral decubitus position as well as hypotensive anesthesia contributed to compression phenomena to the neurovascular structures of the contralateral femoral triangle.46 They also proposed several techniques, which include checking and padding the area of the femoral triangle before surgery and at intervals throughout surgical procedures that may be of long duration. This surgical approach has not been associated with higher overall nerve palsy and has been investigated by numerous authors.18,20 The retractors placed anteriorly can increase the risk of femoral nerve injury.22

Superior gluteal nerve injuries are also clinically relevant and related to the surgical approach. The anterolateral, modified anterolateral, and Hardinge approaches to the hip involve releasing the gluteus medius or releasing the gluteus medius and vastus lateralis in continuity through their fascial connection at the greater trochanter. The superior gluteal nerve exits the sciatic notch and provides innervation to the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae. Jacobs and colleagues47 dissected 10 cadavers to determine the superior gluteal nerve’s susceptibility during the Hardinge surgical approach to the hip. They identified two patterns of nerve distribution. In 18 of the 20 dissections a spray pattern was identified as the nerve divided into numerous branches 1 to 2 cm proximal to the superior boarder of the piriformis. The branches were anterior and slightly distal to the greater sciatic notch and averaged seven in number to the gluteus medius, one to three to the gluteus minimus, and one to the tensor fasciae latae. Also, the distance from the greater trochanteric midpoint to the superior gluteal branches was an average of 6.6 cm (anterior to the midline) and 8.3 cm (posterior to the midline) (Table 55-1).47,48 The second pattern was the transverse neural-trunk pattern and was found in the remaining two dissections—both left hips from two different cadavers. The pattern included short branches to the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles with the terminal branch to the tensor fasciae latae. A thorough understanding of the anatomy and limiting the dissection so the nerve is not disrupted are essential to preserving abductor function when this hip approach is used.

TABLE 55-1 DISTANCE OF THE SUPERIOR GLUTEAL NERVE BRANCHES FROM THE TROCHANTERIC MIDPOINT TO THE POINT OF TERMINATION

| Branches | Distance (cm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | |

| Anterior to the midlateral line | 6.6 | 4.9-8.3 |

| Posterior to the midlateral line | 8.3 | 5.0-12.4 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree