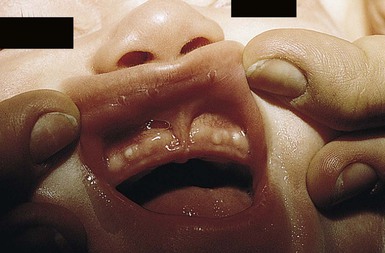

Lucia Diaz, Adelaide A. Hebert Examination of the mucous membranes is an important, yet often overlooked, part of the neonatal evaluation. This chapter discusses abnormal cutaneous findings of the oral, genital, and ocular systems. Many of these abnormalities provide important clues to the diagnosis of underlying disease and/or developmental syndromes in the newborn infant.1,2 See Table 30.1. TABLE 30.1 Benign papular and nodular lesions of the oral cavity Bohn’s nodules are multiple, small cystic structures found along the lingual gum margins and lateral palate (Fig. 30.1). These lesions are commonly found in up to 85% of newborn infants. Bohn’s nodules most likely develop from epithelial remnants of salivary gland tissue or from remnants of the dental lamina. However, some authors refute this idea because mucinous glands are rarely found on the lateral edge of the gingival margins. Bohn’s nodules are felt to be asymptomatic and occur more often in full-term infants than in premature newborns.3–6 Treatment is unnecessary as involution or shedding usually occurs. A congenital epulis is a rare, benign tumor of the newborn. Clinically, the lesion is a solitary soft nodule, measuring from 1 to several millimeters in diameter, and often pedunculated. The lesion represents a hamartoma of the alveolar ridge.7 The epulis forms over the gingival margin, most frequently along the anterior maxillary ridge or the incisor/canine.8,9 Lesions on the alveolar ridge occur twice as often as on the maxilla.7 Female infants are more often affected, with a female to male ratio of 3 : 2. Fetal ovarian estrogen levels were originally thought to account for this predominance, but this concept has been challenged.10 Currently, there is no known cause of these lesions and no teratogenic or genetic association has been reported. Histologic examination shows tightly packed granular cells surrounded by a prominent fibrovascular network. The absence of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and neural elements differentiates the epulis from a granular cell myoblastoma. Lesions may regress spontaneously over time. However, difficulties with feeding and respiration can occur with large or multiple lesions.11 Simple excision is curative; recurrences have not been reported. A congenital ranula is a very rare type of mucocele that results from an obstructed, imperforate, or atretic sublingual or submandibular salivary gland duct. Lesions are found specifically on the anterior floor of the mouth, lateral to the lingual frenulum. The overlying mucosa may be normal in color or have a translucent blue hue. These retention cysts are asymptomatic. Ranulae may resemble mucous retention cysts, dermoid cysts, or cystic hygromas. Differentiation of a ranula from a mucous retention cyst can be confirmed only by histopathologic examination. Although the mucous retention cyst is a true cyst lined by epithelium, the ranula is a pseudocyst. Ranulae may rupture spontaneously during feeding and sucking; however, lesions that enlarge over time should be treated early with marsupialization with packing. In some cases, failure to operate may lead to sialadenitis. If surgery is warranted, the risk of recurrence postoperatively is minimal.12,13 Epstein’s pearls are benign cystic lesions that occur along the median palatal raphe, most commonly at the junction of the hard and soft palates (Fig. 30.2). Lesions are multiple and small, ranging in size from less than a millimeter to several millimeters in diameter. The overall appearance is similar to that of Bohn’s nodules, but the location and etiology make this a distinct entity. Epstein’s pearls are common, occurring in 60–85% of newborn infants. Japanese newborns are most commonly affected (up to 92%), followed by Caucasians and African-Americans.4,6,14 Epstein’s pearls are epidermal inclusion cysts formed during the fusion of the soft and hard palates, and contain desquamated keratin within their lumina. They are considered the counterpart of milia, which are commonly seen on the faces of neonates. No therapy is indicated, as most lesions rupture spontaneously within the first few weeks to months of life.3,4,14 An eruption cyst (or eruption hematoma) is a circumscribed fluctuant swelling that develops over the site of an erupting tooth (Fig. 30.3). Lesions in the newborn may occur secondary to natal or neonatal teeth, but these cysts are more commonly associated with the eruption of deciduous or permanent teeth. Eruption cysts most commonly develop on the alveolar ridge of the maxilla or mandible. Size varies with the type of tooth overlaid, but most lesions are approximately 0.6 cm in diameter. The surface of the cyst may appear flesh-colored or have a bluish-red to blue-black color if the cyst cavity contains blood. Although removal of the tissue overlying the tooth may aid in its eruption, most eruption cysts resolve spontaneously within several weeks.15 Ectopic thyroid tissue is defined by the development of thyroid tissue outside the usual pretracheal position (inferior to the thyroid cartilage). This abnormality results from an arrest or irregularity in thyroid descent during embryologic development. Ectopic thyroid tissue, also referred to as a thyroglossal duct cyst, may be classified as lingual, sublingual, pretracheal, or substernal. Lingual is the most common type, representing over 90% of cases. A lingual thyroglossal duct cyst presents as a painless, nodular mass in the cervical midline or at the base of the tongue between the circumvallate papillae and the epiglottis. Lesions may be present at birth or develop in early infancy. However, most become evident during the first or second decades of life, at which time associated symptoms may occur.16–19 Thyroglossal duct cysts are a rare but serious cause of airway obstruction in newborns and infants: mortality rates of up to 43% have been reported. Although usually asymptomatic, lesions may be associated with cough, dysphagia, hemorrhage, or pain. If a cutaneous tract is present, mucous drainage can occur. Fordyce spots are collections of normal sebaceous glands within the oral cavity. Lesions appear as white to yellow macules and papules visible through the transparent oral mucosa. The papules measure 1–3 mm and may be clustered (Fig. 30.4). Plaques form when large numbers of sebaceous glands coalesce. Sebaceous hyperplasia is most commonly seen on the upper lip, but may also be evident on the buccal mucosa, tongue, gingiva, or palate. No treatment is warranted, as these lesions are asymptomatic, resolve spontaneously, and are of no medical consequence.6 Superpulsed CO2 laser has been reported to be safe and effective in a small number of cases.20 Nevus sebaceus (see Chapter 26) is a common congenital lesion that usually occurs on the scalp and face, but may be seen in continuity with growths in the oral cavity. Cutaneous lesions present as yellow, verrucous plaques (Fig. 30.5) that enlarge with the growth of the child and often become thicker in puberty. Mucosal lesions most often present as linear papillomatous plaques on the gingivae, palate, tongue and buccal mucosa. Intraoral lesions can be associated with dental anomalies and mandibular cysts.21 Extensive and multiple nevus sebaceus may be associated with cerebral, ocular, and skeletal abnormalities as part of sebaceous nevus syndrome. White sponge nevus is a rare, benign condition inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Typical lesions are asymptomatic white plaques in which the oral mucosa appears thickened and folded, with a spongy texture (Fig. 30.6). The most common location for a white sponge nevus is on the buccal mucosa, often in a bilateral distribution. Extraoral locations, such as labial, nasal, vaginal, esophageal, and anal mucosa, are uncommon, and such lesions usually do not occur in the absence of oral involvement.22 The white sponge nevus is most often present at birth or discovered during early childhood.23 The clinical differential diagnosis of white sponge nevus includes candidiasis, leukoderma, leukoplakia, lichen planus, and local irritation. White sponge nevus is sometimes seen in association with pachyonychia congenita. However, the clinical and histologic findings are usually characteristic enough to differentiate this condition from other white mucosal lesions.24 The histopathology of a white sponge nevus shows epithelial thickening with hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. The suprabasal cells exhibit intracellular edema with pyknotic nuclei and compact aggregates of keratin intermediate filaments within the upper spinous layer.25 White sponge nevus is a benign disorder that does not require treatment. The granular cell tumor, first described in 1926, was originally thought to arise from skeletal muscle and was hence named a granular cell myoblastoma.26 However, more recent immunohistochemical testing suggests a neural origin.27 Intraoral granular cell tumors most commonly occur on the tongue, but may also affect the lips and gingiva. The lesion is typically a solitary, small (<3 cm), firm, asymptomatic nodule, with a smooth, nonulcerated surface. These lesions may rarely cause obstruction of the oral cavity.28 The differential diagnosis includes other benign neural neoplasms (neuromas, neurofibromas), and vascular tumors (hemangiomas, venous malformations).29–32 Histologically, large, eosinophilic granular cells are arranged in clusters and fascicles. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium may be present, mimicking squamous cell carcinoma.33 Although the majority of granular cell tumors are entirely benign, these tumors can be locally invasive and metastases have been rarely reported. Surgical excision is recommended and curative. Recurrences are uncommon.34 A neurofibroma is a tumor of neural origin, which may occur as an isolated finding or in association with the syndrome of neurofibromatosis. Neurofibromatosis may be difficult to diagnose in the newborn period, when many of the features of the syndrome are not yet evident. Neurofibromas may be found on the skin or within the oral cavity, although intraoral lesions are exceedingly rare in the newborn. The most common intraoral location is the tongue, though tumors have also been observed over the buccal mucosa and palate. Oral lesions are typically asymptomatic, slow-growing, soft nodules, of the same color as the surrounding mucosa. Neurofibromas range in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. Histologically, the tumor is unencapsulated and composed of Schwann cells, perineural cells, and fibroblasts. Neurofibromas are benign and can be electively surgically excised with little risk of recurrence.35,36 The oral mucous membranes are the most frequent site for yeast colonization in infants. Candida albicans causes the white pseudomembranes (thrush) on the palate, gums, gingivae, tongue or buccal mucosa. Removal of the plaques leaves an underlying area of erythema. This is a clinical diagnosis that can be confirmed with KOH or culture. Thrush can be treated with nystatin oral suspension 200 000 units (2 mL) on the tongue four times daily for 7–10 days. Fluconazole may be more effective than oral nystatin and should be considered for treatment failures. Treatment of immunocompromised oropharyngeal candidiasis with systemic azoles can be beneficial. Black hairy tongue is characterized by accumulation of keratin on the filiform papillae that give the central dorsal tongue a brown-black appearance (Fig. 30.7). This condition is usually seen in adults but has been reported in an infant as young as 2 months of age.37 Although the etiology is unknown, black hairy tongue is attributed to bacterial or yeast infections as well as chronic antibiotic use. Treatment involves improving oral hygiene. Brushing of the tongue with toothpaste three times a day often helps this condition. Herpangina and HFMD (see Chapter 13) are common illnesses caused by echoviruses, predominantly coxsackie A16. Herpangina is characterized by fever, sore throat, anorexia, and sometimes abdominal pain. Multiple 1–2 mm vesicles develop on the uvula, tonsils, pharynx, and soft palate. In HFMD, patients have vesicles and erosions on the buccal mucosa in addition to the oral lesions of herpangina. Patients also have oval gray-white vesicles and erythematous papules and macules on the hands, feet and buttocks. The diagnosis of both diagnoses above is made clinically but can be confirmed with PCR.38 Treatment is supportive and the course lasts less than 1 week. Herpetic oral infections are usually caused by HSV-1 (see Chapter 13). There may be a prodrome of fever, vomiting, and irritability. The infant may also have tender cervical or submental lymphadenopathy. Small vesicles on an erythematous base may develop on the tongue, palate, pharynx, buccal mucosa, lips and floor of the mouth. In contrast to aphthous ulcers, the lesions coalesce into irregular shallow ulcers. Due to the pain, the infant may have difficulty with feeding. Diagnosis can be confirmed with a Tzanck smear, viral culture, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Treatment includes supportive care and oral acyclovir. The course usually lasts less than 2 weeks. Oral verrucae or papillomas occur less frequently in children and infants than other forms of HPV infection (see Chapter 13).39 Exophytic, pedunculated or sessile papules with a papillated white or pink surface can present anywhere on the oral mucosa, but are most common on the tongue, palate, and labial mucosa.39 When associated with laryngeal papillomas the infant or child may also have a hoarse voice or respiratory symptoms.40 Vertical transmission of HPV during delivery, or in utero is the most likely, but horizontal transmission by household members and transmission from sexual abuse are also possible.39–41 If necessary, a clinical diagnosis of oral HPV infection can be confirmed by biopsy. HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 are most commonly found in oral papillomas. Treatment should depend on the severity of the presentation and associated symptoms. Treatment options include watchful waiting (as most spontaneously resolve within 1–2 years); destructive modalities such as cryotherapy and laser; and excision by tangential shave.39 IH of the mucosa in newborns most commonly develop within the first few days to weeks of life. Most often IH involve the oral mucosa (lips, buccal mucosa, or palate), but can also involve the nasal and ocular mucosa (Fig. 30.8). Superficial lesions consist of bright red papules, nodules or plaques, whereas deeper lesions are generally flesh colored, and may have a bluish hue or overlying telangiectasias. Lesions with a combination of both superficial and deep features are also common. Hemangiomas of the oral cavity are prone to trauma, which can lead to ulceration and/or bleeding, particularly during the newborn period. The lip can also be a high-risk location for deformity and scarring, particularly when lesions ulcerate or are superficial and cross the vermillion border. There is also a known association between hemangiomas in a cervicofacial, or ‘beard’ distribution (preauricular skin, chin, anterior neck, or lower lip) and airway hemangioma. At-risk infants should be followed closely during the newborn period for the development of stridor or other signs of airway compromise, in which case direct visualization of the airway can provide a definitive diagnosis.42,43 Treatment indications and options for hemangioma treatment are discussed in Chapter 21. Ulceration of a lip hemangioma can be particularly difficult to manage owing to the challenges of wound care in this location, and because associated pain can interfere with feeding. Such cases may require additional management with beta blockers, corticosteroids, laser, or excisional surgery.44,45 Lymphatic malformations (LM) are benign, structural malformations of lymphatic vessels, and are much less common than hemangiomas. They are congenital, but sometimes do not manifest until later in childhood. No known sexual predilection or hereditary predisposition exists. Unlike hemangiomas, LM remain static or undergo slow expansion over time, and rarely undergo any significant degree of involution.46–48 The cervicofacial region is a common site for LM. Lesions may be localized, diffuse or multiple in distribution, and may be microcystic (‘lymphangioma’), macrocystic (‘cystic hygroma’) or combined. Microcystic lesions of the skin present as translucent papules or nodules, which often turn red or purpuric due to intralesional bleeding (Fig. 30.9). The most common location for intraoral LM is the tongue, although the lips, buccal mucosa, palate, or alveolar ridges may also be affected. LM of the tongue most commonly affects the dorsal anterior two-thirds and may result in macroglossia and difficulties with feeding and speech.47–49 Large macrocystic (Fig. 30.10) or combined LM of the posterior triangle of the neck, which often present as fluctuant, flesh-colored tumors, may also involve the floor or the mouth and submandibular space. Bacterial cellulitis occurring within cervicofacial LM is potentially dangerous because of the risks of airway compromise. In such instances, systemic antibiotics should be administered at the first sign of swelling, pain, redness, or systemic toxicity. Histologically, LM consist of multiple lymphatic channels lined by single or multiple layers of endothelial cells. Treatment is rarely necessary in the first year of life, and is generally reserved for lesions causing functional compromise or cosmetic deformity. MRI is the best means of determining lesion extent and microcystic or macrocystic morphology, which is generally necessary before decisions regarding treatment can be made. The mainstay of therapy for LM includes surgery and/or sclerotherapy, though cure is rarely achieved except for the smallest, most well-localized lesion. Attempts at surgical resection are often accompanied by a variety of intraoperative and postoperative complications, including recurrence. Sclerotherapy with agents such as absolute ethanol, sodium tetradecyl sulfate, or doxycycline, can be used for treatment of macrocystic LM, alone or in conjunction with surgical techniques.50,51 Microcystic LM of the tongue can also be treated with laser photocoagulation, though this is also a temporary measure.52,53 Venous malformations (VM) are slow-flow structural anomalies of the venous vasculature, which are generally present at birth but may not manifest until later in childhood. Lesions most commonly involve the face and oropharynx, but may occur in any anatomic location. Though usually solitary, lesions may be multiple, especially when associated with the autosomal dominant, familial cutaneous–mucosal VM syndrome, or blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, both characterized by small dome-shaped lesions. VMs are bluish, compressible nodules, which slowly refill upon release and are often intermittently painful. Lesions may result in skeletal alterations, such as facial asymmetry, dental malalignment, open mouth deformity, and bony hypertrophy. MRI with or without venography or Doppler ultrasound is the best way to confirm the diagnosis of a venous malformation and determine the extent of tissue involvement. In addition, the presence of phleboliths is highly characteristic of the diagnosis. Extensive lesions may be complicated by a localized, intravascular coagulopathy, characterized by a normal or moderately low platelet count and fibrinogen, increased d-dimers, and normal prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times. VMs characteristically undergo slow expansion over time. Treatment is rarely necessary in the first years of life, and is generally reserved for lesions leading to functional compromise, bleeding, coagulopathy, or cosmetic disfigurement. Depending on the location and size of the lesion, surgical excision and/or sclerotherapy can be considered.54 A port-wine stain (PWS) is a common capillary malformation in newborns. Histopathology shows a normal number of dilated capillaries in the superficial dermis. The well-demarcated vascular stains grow in proportion to the growth of the child. An orodental PWS may lead to hyperplasia of the gingivae, oral bleeding, overgrowth of bony structures, and possible interruption in dental eruption. This is thought to be from increased blood flow to the areas.55 Pyogenic granuloma is an acquired vascular lesion that most commonly presents on the skin, but is not uncommonly seen on the mucous membranes. The typical clinical presentation is a solitary red papule with a collarette of scale at the base that occurs in areas prone to trauma and may bleed. Treatment includes shave excision with electrodesiccation of the base, which helps prevent recurrence. Pulsed-dye laser has been used in smaller lesions.56 Macroglossia is defined as a resting tongue that protrudes beyond the teeth or gum line (Figs 30.11, 30.12). When this is present in a newborn, a thorough evaluation should be performed to rule out genetic, metabolic, or other possibly contributing factors. True macroglossia may be ‘primary,’ whereby the tongue is enlarged due to hyperplasia or hypertrophy of normal lingual structures, or, more commonly, ‘secondary’ to an underlying process, as with a lymphangioma or in amyloidosis (Box 30.1).

Neonatal Mucous Membrane Disorders

Introduction

Disorders of the oral mucous membranes

Developmental defects, growths, and hamartomas

Lesion

Morphology

Most common location

Bohn’s nodules

Multiple, small cysts

Gingival margin, lateral palate

Congenital epulis

Pedunculated, soft nodule from 1 mm to several cm in diameter

Gingival margin

Congenital ranula

Translucent, firm papule or nodule

Anterior floor of mouth, lateral to lingual frenulum

Epstein’s pearls

Multiple, tiny (< few mm) cysts

Median palatal raphe

Eruption cysts

Circumscribed, fluctuant swelling; may have bluish-red to black surface if hemorrhage has occurred

Alveolar ridge of mandible or maxilla

Granular cell tumor

Small (<3 cm in diameter), firm, flesh-colored nodule

Tongue

Hemangioma

Red to blue, soft to semi-firm nodule

Lip, buccal mucosa, palate

Lymphangioma

Translucent papules or nodule

Tongue

Neurofibroma

Soft, flesh-colored nodule

Tongue

Nevus sebaceus

Verrucous yellow plaques

Lip, gingiva

Venous malformation

Bluish, compressible nodule; often intermittently painful

Oropharynx

Verrucae

Papillomatous white or pink papules

Lip, tongue, palate

White sponge nevus

White plaque with thick, folded surface

Buccal mucosa, tongue

Bohn’s nodules

Congenital epulis

Congenital ranula

Epstein’s pearls

Eruption cysts

Ectopic thyroid tissue

Sebaceous hyperplasia of the lip (Fordyce spots or granules)

Nevus sebaceus

White sponge nevus (of Cannon)

Granular cell tumor

Neurofibroma

Infections

Thrush

Black hairy tongue (lingua pilosa nigra)

Herpangina and hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD)

Herpetic gingivostomatitis

Human papillomavirus

Vascular lesions (see Chapters 21 and 22)

Infantile hemangiomas (IH)

Lymphatic malformations

Venous malformations

Port-wine stain

Pyogenic granuloma

Signs of extracutaneous disease

Macroglossia

Neonatal Mucous Membrane Disorders

30