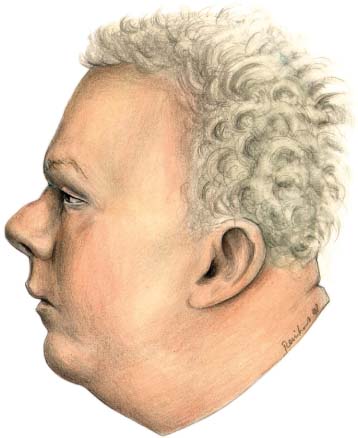

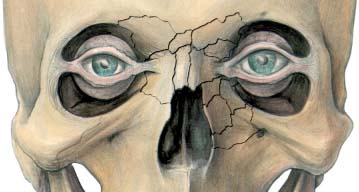

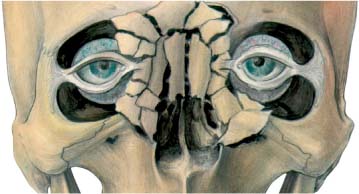

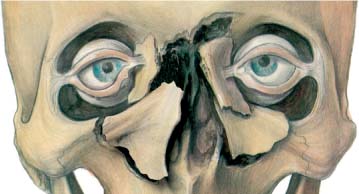

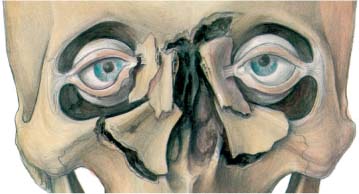

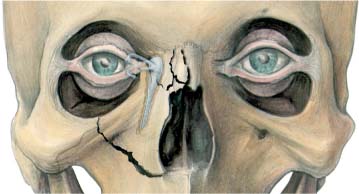

20 Naso-ethmoid Fractures Naso-ethmoid fractures represent a spectrum of injuries, from simple nasal fractures with undetectable ethmoid involvement through to grossly comminuted and compounded naso-ethmoid fractures involving the base of the skull and significant displacement. The tentlike nasal bone is relatively thick, especially in the bridge area, but it is the triangular shape that provides the strength. Further strengthening is given by the “tent pole” of the vertical bony septum. Thus, there is considerable strength against fracture from a direct anterior blow. A blow laterally, however, meets little structural resistance; hence the relative frequency of simple fractured noses that have minimal effect on the ethmoids or the base of the skull. Once the nasal “tent” collapses, forces are dissipated into the air cells, which act like air bags. While this mechanically protects the base of the skull, collapse of the naso-ethmoid complex may occur relatively easily if these air cells are large and pneumatized. With minimal force the whole complex may collapse, frequently as one unit, into the frontal sinus. Thus a naso-ethmoid fracture may occur with relatively minimal injuries in some patients. Severe forces, however, may extend the fracture into the base of the skull, frequently seen as a cerebrospinal fluid leak, as the cribriform plate is ruptured. The medial canthus has a small attachment point to the lacrimal crest. Loss of this attachment leaves an ugly, “blunt” medial canthus that is further damaged by the inevitable lateral drift. The resultant defect is very un-sightly. The lacrimal apparatus is more frequently damaged by lacerations and more rarely by secondary bony injury. On occasion, damage may be iatrogenic during osteosynthesis stabilization of the fractures. Soft-tissue injuries are readily evaluated by clinical examination. Gross swelling may obliterate the canthal attachment but careful exploration normally overcomes this confusion. This exploration should be particularly directed at pulling the canthus to ensure that it is still attached to stable bone. If the bone attachment has itself been fractured, lateral displacement of the canthus should be evaluated. When the lacrimal apparatus is damaged, it is most frequently by direct laceration. However, this is a rare complication. Lacerations in this area must be carefully explored. If doubt remains, radiological examination may be indicated. However, even where swelling is pronounced, careful clinical examination will normally yield a clear understanding of the extent of the fractures. This is important for requesting radiographic examinations that are well “targeted,” so that maximum information is generated. Fig. 20.1 A simple naso-ethmoid fracture illustrating the depression of the soft-tissue nasion. This tilts the nose back producing the “pig snout” appearance of the nares. Fig. 20.2 Ayliffe classification type 0. Undisplaced. Fig. 20.3 Ayliffe classificationtype I. Comminuted but “platable.” Fig. 20.4 Ayliffe classification type II. Requiring bone graft. Fig. 20.5 Ayliffe classification type III. Canthal disruption, requiring canthoplexy. Fig. 20.6 Ayliffe classification type IV. Lacrimal reconstruction.

Introduction

Anatomical Considerations

Clinical Examination

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree