and Peter M. Prendergast2

(1)

Elysium Aesthetics, Bogota, Colombia

(2)

Venus Medical, Dublin, Ireland

Introduction

Sculpting the human body in order to improve definition is impossible without a thorough knowledge of muscular anatomy. The surgeon must also develop an artist’s eye so that the form ideally created by the superficial musculature can be “visualized” and then revealed through selective lipoplasty techniques [1, 2]. In most individuals with a normal body mass index, an athletic and toned appearance can be created through high-definition body sculpting by removing fat and highlighting major muscle groups [2]. The anatomy and form of the most important muscles and muscle groups for high-definition lipoplasty are detailed in this chapter. These include muscles of the trunk, shoulder, upper arm, hip, thigh, and leg. The salient features of the muscular anatomy relevant to body contouring are outlined, such as the origin, insertion, orientation, form created, and relationship to adjacent muscle groups.

Trunk Muscles

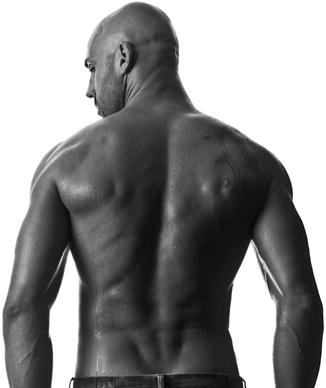

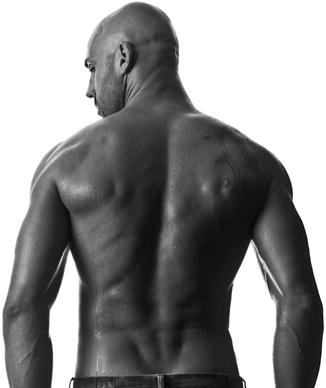

The trunk muscles consist of large and small groups arranged anteriorly and posteriorly over the abdomen and back, respectively. They also include the chest wall muscles. They form the muscular body wall, where they connect the rib cage to the bony pelvis. The trunk muscles have various actions on the torso, including flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation. The definition of the trunk muscles provides an appearance of athleticism, strength, and health. In men, the posterior trunk muscles create a V-shaped form, or triangular wedge; the broad latissimus dorsi tapers inferiorly to a narrow waist (Fig. 2.1). Anteriorly, the fleshy bellies of the rectus abdominis bulge between tendinous intersections, and the pectoralis major provides a convex muscular mass over the chest (Fig. 2.2). In women, the anterior and posterior trunk muscles between the rib cage and pelvis narrow the waist. Posteriorly, the broad V shape is lacking, but the smaller erector spinae provide attractive definition on either side of the midline (Fig. 2.3). Anteriorly, a subtle shadow over linea alba and at the lateral borders of the rectus abdominis creates beautiful definition of the female abdomen (Fig. 2.4) [2].

Fig. 2.1

The posterior male trunk. A “V” shape is produced by the back muscles tapering inferiorly to a narrow waist

Fig. 2.2

Anterior male abdomen. The major muscle groups and their tendinous intersections create a highly defined appearance

Fig. 2.3

Definition and form of the female back. Note the midline groove between the spinous muscles and the dimples in the lower back marking the location of the posterior superior iliac spines

Fig. 2.4

Anterior female abdomen. The most defining features in the athletic female abdomen are the linea alba and linea semilunaris

Rectus Abdominis

This vertically oriented paired strap muscle occupies most of the central part of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 2.5). It is narrow and thick inferiorly and broader and flatter in the upper abdomen. The rectus abdominis arises from the symphysis, crest, and pecten of the pubis and runs upward to insert into the xiphoid process and costal cartilages of the fifth to seventh ribs. Its main action is to flex the trunk. The inferior part of the rectus abdominis is covered only on its anterior surface by the rectus sheath, and above the costal margin, the muscle lies directly on the costal cartilages. The paired rectus abdominis is separated in the midline by the linea alba and by three horizontal tendinous intersections. These fibrous bands are usually located at the level of the xiphoid process, at or just above the umbilicus, and halfway between these two. A fourth tendinous intersection may be visible below the umbilicus and marks the location of the arcuate line. The tendinous intersections on one side may be in line with the contralateral side or may be at different levels, giving an asymmetrical appearance to the anterior abdominal musculature. The intersections closest to the umbilicus tend to run horizontally, whereas the uppermost tendinous intersections often run more diagonally. The orientation of tendinous intersections is highly variable, and all may be horizontal. Careful palpation of the anterior abdominal wall in slim individuals confirms the surface anatomy. The intersections divide the muscle into segments of fleshy protruding bellies that create the quintessential muscular male abdomen commonly referred to as the six-pack [2]. The superior borders of the upper segments usually coincide with the inferior margin of the pectoralis major, but variations exist. The muscle may continue superiorly under the pectoralis major or may end lower down, exposing the costal cartilages and creating a depression between the lower border of the pectoralis major and the superior border of the rectus abdominis. The borders of the segments created by the intersections are rounded. The lateral border of the rectus abdominis is often visible as a vertical groove in the anterior abdominal wall between the ninth costal cartilage and the pubic tubercle. This semilunar line typically runs along a line drawn from the midpoint of the clavicle to the middle of the thigh. It starts superiorly as a depression just below and medial to the nipple in men, runs inferiorly between the anterior limits of the muscular part of the external oblique and the lateral border of the rectus abdominis, and expands into a triangular area over the aponeurosis of the external oblique above the inguinal ligament. In the midline, diastasis or separation of the recti muscles with widening of the linea alba occurs following pregnancy or as a congenital deformity and may result in an abnormally convex abdominal contour. Plication of the anterior or posterior rectus sheath, sometimes combined with plication of the external oblique aponeurosis, improves this myoaponeurotic deformity [3]. When the body is hyperextended, stretching the skin and muscle over the rib cage, a thoracic arch is easily seen where the costal cartilages meet the sternum in the midline. Even at rest, this may be seen in females and in thin individuals. The arch forms an angle of approximately 90° in males and 60° in females. In males, a more rounded arch is created by the costal margin laterally and the highest tendinous intersection of the rectus abdominis medially. The umbilicus or navel lies within a defect in the linea alba, opposite the fourth lumbar vertebra, and about midway between the xiphoid process and symphysis pubis. In athletic males, a sharp rim is usually present at the upper border of the umbilicus, whereas the lower border is less well defined. In females, a periumbilical fat pad deepens the navel and obscures its borders.

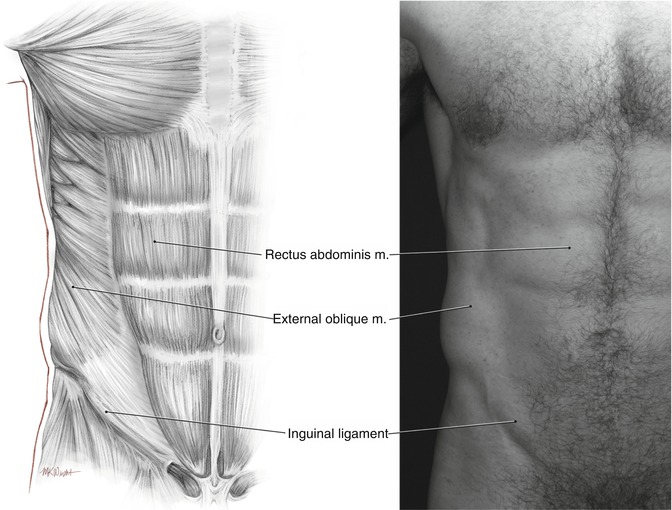

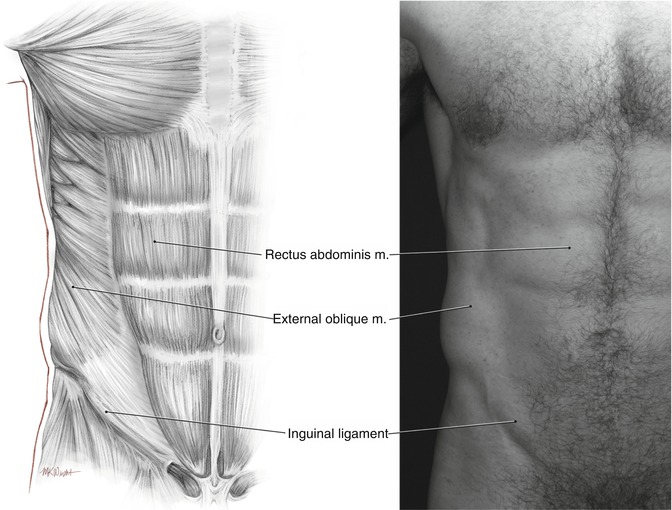

Fig. 2.5

Rectus abdominis. This represents the most important muscle in high-definition body sculpting of the anterior abdominal wall

External Oblique

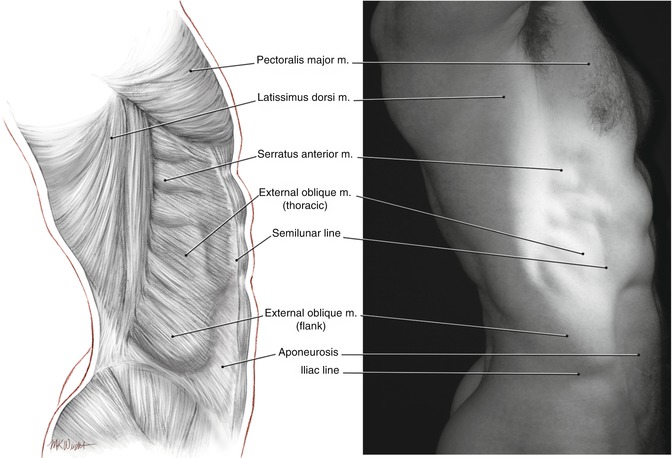

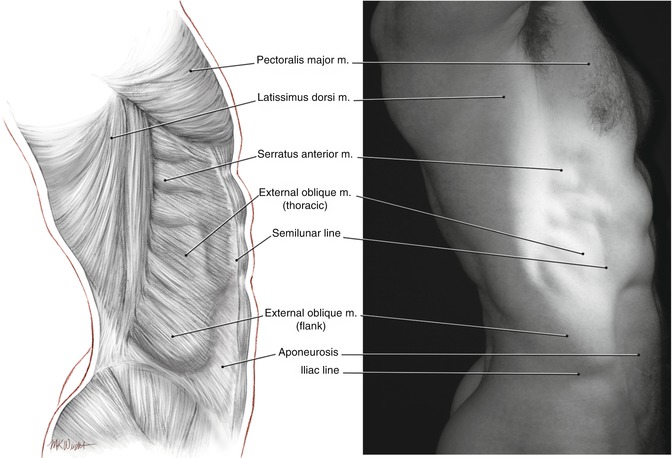

This muscle forms the fleshy part of the lateral abdominal wall as its fibers pass inferiorly and inferomedially superficial to the other flat muscles (Fig. 2.6). It originates from the external and inferior surfaces of the lower 7–8 ribs. The external oblique has two parts: an upper thoracic portion and a lower flank portion. The thoracic portion consists of separate elongated bundles of muscle that run parallel to one another and in a straight line from the external surfaces of the ribs to their aponeurosis at the semilunar line. The lower fibers of the thoracic portion form a transitional zone above the flank portion that coincides with the waist. The anterior edge of the thoracic portion of the external oblique is jagged or irregular where it inserts into its own aponeurosis as separate bundles. The flank portion of the muscle runs from the external surfaces of the inferior ribs to the anterior half of the lip of the iliac crest posteriorly and the external oblique aponeurosis and linea alba anteriorly. The flank pad represents a fleshy trapezoid between the ribs and pelvis that wraps around the waist. This comprises the flank portion of the external oblique anteriorly and a flank fat pad posteriorly. Even with good muscular development, external oblique muscle fibers are not visible in the smooth, convex flank pad. The inferior margin of the flank pad is the iliac line. Since the muscle fibers of the external oblique insert into the iliac crest, an iliac line lower than this is created by ptotic fat, and not muscle. The most posterior fibers of the flank portion of the external oblique pass vertically from the lower two ribs to insert into the iliac crest, creating a posterior free border. These fibers do not insert into the thoracolumbar fascia and constitute the anterior border of the inferior lumbar triangle of Petit, with posterior and inferior borders formed by the latissimus dorsi and iliac crest, respectively. Unusual cases of herniation through Petit’s triangle have been reported [4]. This triangle is usually covered with the fat pad. The external oblique becomes aponeurotic medially at the midclavicular line and inferiorly at the spinoumbilical line (between anterior superior iliac spine and umbilicus). The aponeurosis passes anterior to the rectus abdominis as part of the rectus sheath and decussates with aponeurotic fibers of the contralateral external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis at the midline. The external oblique aponeurosis passes the midline to be continuous with the aponeurosis of the contralateral internal oblique. Functionally, the external oblique and the contralateral internal oblique can be considered as a digastric muscle, since their simultaneous action flexes and rotates the abdomen, as occurs when the shoulder is turned toward the contralateral hip. The inferolateral fibers of the external oblique, below the spinoumbilical line, turn backward and upward between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle to form the inguinal ligament. A triangular tendinous expansion occurs just below the spinoumbilical line and lateral to the rectus abdominis. There may be a slight groove above and parallel to the inguinal ligament in this area created by the internal oblique muscle lying beneath. The tip of the tenth rib marks the base of the rib cage and the superior limit of the abdominal portion of the external oblique [5]. A small triangular depression along the semilunar line occurs here in athletic people. Subdermal lipoplasty is used to create a controlled depression in this area to enhance definition of the anterolateral abdominal wall.

Fig. 2.6

The lateral abdominal wall. The external oblique muscle predominates, superiorly as the thoracic portion and inferiorly as the less well-defined flank portion

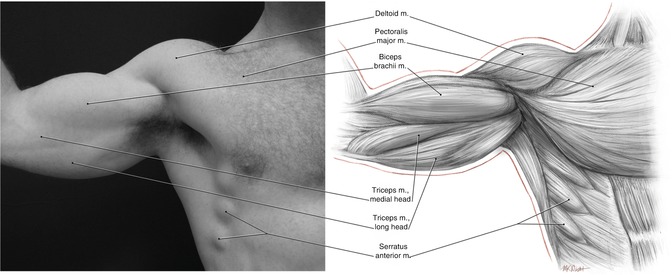

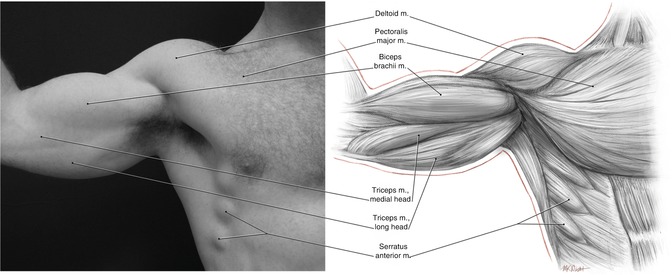

Serratus Anterior

This quadrilateral muscle originates anteriorly as fingerlike bundles from the external surfaces of the upper 8–9 ribs and wraps around the rib cage to insert into the vertical, medial edge of the scapula. It acts to draw the scapula laterally and around the rib cage, as in punching. The inferior part of the muscle rotates the tip of the scapula laterally, raising the arm. In muscular individuals, the anterior parts of the lowest 3–4 digitations of the serratus anterior can be seen on the lateral chest wall as they mingle with fibers of the external oblique (Fig. 2.7). The superior bundle is usually seen immediately below or at the inferior margin of the pectoralis major. The digitations of the serratus anterior are easily distinguished from the external oblique as thicker, more pronounced bundles of muscle that are oriented more horizontally relative to the fibers of the external oblique. A line drawn from the male nipple to the posterior superior iliac spine approximates the anterior extent of the visible portion of the serratus anterior over the torso as seen in profile view [5]. The rest of the serratus anterior is hidden from view by the pectoralis major superiorly and the latissimus dorsi posteriorly or is present between the two where it forms the medial wall of the axilla. Posteriorly, the mass of the serratus anterior can be appreciated where it bulges underneath the flat latissimus dorsi muscle that covers it. Its posterior limit sometimes extends more medial to the scapula where its fibers insert into part of the rhomboid major. Defining the serratus anterior plays an important role in high-definition body sculpting in male patients.

Fig. 2.7

The superolateral abdominal wall. The serratus anterior is clearly visible as three bulging slips of muscle below the lateral aspect of pectoralis major

Pectoralis Major

The pectoralis major forms most of the muscle bulk of the chest and gives the chest a smooth, convex form, particularly when the muscle is well developed (Fig. 2.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree