40. Midface Rejuvenation

Sumeet Sorel Teotia, Sami U. Khan, Foad Nahai

The human “middle of the face,” often called midface, is a loosely applied anatomic term that mainly focuses on the soft transition from the lower eyelid inferiorly toward the rounder, upper cheek as it transitions into the lateral face, upper lip, and soft tissue of the nasal sidewall. Thus a midface problem arises when any anatomic component within this region begins the aging process.

HISTORY

In the early twentieth century, surgical procedures to address facial aging consisted of skin and subcutaneous facelifts. These interventions had no effect on the midface.

RENAISSANCE ERA (1970s)1

■ Early 1970s: Skoog2 described subsuperficial musculoaponeurotic system (sub-SMAS) dissection.

■ 1976: Mitz and Peyronie3 defined SMAS.

■ Late 1970s: Focus changed to dissecting, dividing, and repositioning the SMAS.

■ These advances improved the appearance of the lower third of the face and neck, but not the midface.

DIFFERENT PLANES OF DISSECTION ERA (1980-1992)1

■ Craniofacial surgeons, like Tessier,4 introduced subperiosteal approaches to better reposition facial soft tissues.

• “Mask lift”: subperiosteal dissection of the malar region, zygomatic arches, and orbital region

• Soft tissues dissected and redraped over the facial skeleton to rejuvenate the face

■ 1984: Psillakis5 attempted to reposition/elevate the soft tissues of the orbital and malar region by undermining the superficial temporofrontal fascia and fixing it to the aponeurosis of the temporalis.

■ 1990: Hamra6 introduced the deep plane rhytidectomy, combining a Skoog-type sub-SMAS dissection over the zygomaticus musculature and medially to fully release the nasolabial fold. This allowed total release of the all SMAS attachments. The flap was advanced laterally and fixed to the superficial temporal fascia.

■ 1992: Hamra7 refined his technique to improve midface rejuvenation with the “composite rhytidectomy.” Through a transblepharoplasty incision, the orbicularis oculi was undermined, and this plane was connected to the facelift dissection plane. This created a composite flap of orbicularis muscle, cheek fat, and platysma, which, when repositioned, addressed the three major areas of soft tissue ptosis.

■ 1992: Barton8 provided a better understanding of the sub-SMAS plane and its relationship to the nasolabial fold. Anatomically, within the medial cheek the SMAS becomes the investing fascia of the zygomaticus major and minor.

• Thus, simple SMAS manipulation does not significantly improve the appearance of the deepened nasolabial fold.

• He recommended that, to address the fold, medial to the zygomaticus musculature the dissection must transition to skin-subcutaneous tissue plane to release the tethering effect of the SMAS.

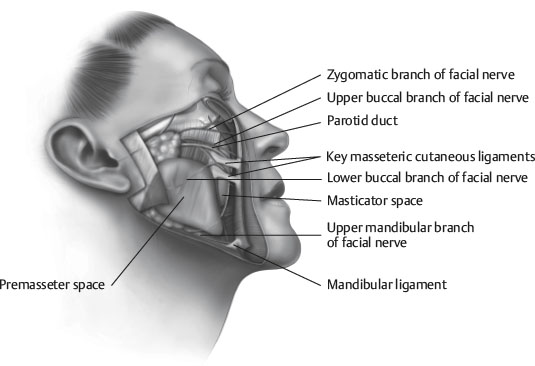

■ 1993: Owsley9 defined the malar fat pad as a “discrete area of bulky subcutaneous fat, which overlies the maxillary zygomatic region.” The fat pad is triangular in shape and has its base at the nasolabial fold. He advocated dissecting below the fat pad to completely mobilize it and then suspending it under tension to the subcutaneous fascia over the malar eminence with a vector perpendicular to the nasolabial crease (Fig. 40-1).

Fig. 40-1 Elevation and mobilization of the malar fat pad.

ADVANCED TECHNIQUES ERA (1992-1999)2

■ 1992: Terino10 described his concept of addressing the “fourth plane.”

• Advocated the use of alloplastic facial augmentation in conjunction with concepts of facial zonal anatomy to address volume loss in the midface

■ 1993: Flowers11 describes the tear trough deformity and used alloplastic implants for volumetric correction.

■ 1994: Coleman12 posed the question “Should we support and fill or should we excise and suspend?”

• Popularized lipoinfiltration for soft tissue augmentation and lifting in the periorbital region through fat grafting

■ 1994: Facial surgeons, including Fuente del Campo,13 Isse,14 and Ramirez,15 started to incorporate the endoscope into facial rejuvenation.

• 1995: Ramirez described six types of procedure combinations for rejuvenation of the upper and middle third of the face.

• Types four through six addressed the midface and consisted of full open, full endoscopic, and biplanar combined procedures.

VECTORS AND VOLUME ERA (1999-PRESENT)1

■ Concepts of volume management of the midface and correct vector of elevation/pull

■ Little15,16 described a volumetric approach to midface rejuvenation, both in the subcutaneous and subperiosteal plane.

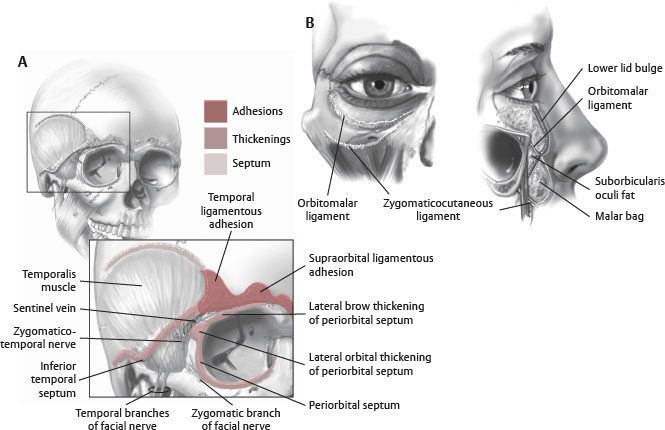

■ Significant anatomic studies refined the complex anatomy of the midface/periorbital region.

■ Vectors of pull in rejuvenative surgery were reassessed, and a more vertically oriented direction of pull was advocated, especially for procedures addressing the midface.

PERTINENT ANATOMY

BASIC DEFINITION OF THE MIDFACE

■ Portion of the cheek medial to a line extending from the frontal process of the zygoma to the oral commissure and from the lower lid above to the nasolabial fold below17

■ Anatomically, the midface thus encompasses complex relationships of the lower lid, the nasolabial fold, the upper lip, and the malar eminence/cheek.

BASIC ANATOMY18,19

■ Skeleton

• Main determinant of contour of the midface, although the thickness of the soft tissue component is important, especially with changes in aging

• Serves as platform for attachment of the overlying ligaments and muscles, which support the midface soft tissues

• Upper/outer prezygomatic portion: Overlies the body of the zygoma

• Lower/medial portion: Overlies the maxilla; covers the vestibule of the oral cavity

■ Soft tissue

• Suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF)

► Posterior to muscle

► May require reduction, repositioning, or nothing

• Temporal fat pad

► Superior to zygoma between superficial and deep layers of temporal fascia

• Malar fat pad

► Main midface soft tissue structure

► Triangular

► Changes with age: Flattens, loses projection, loses volume, elongates, becomes narrower, and displaces inferiorly

• Buccal fat pad

► Superficial to the periosteum overlying the maxilla at the lateral buttress

► Important support structure for the cheek mass

• SMAS

► Adipofascial layer superficial to the parotid fascia and mimetic muscles

► Laterally anchored to the parotid fascia and at the osteocutaneous ligament of the zygoma and mandible

► Midface elevation often achieved by elevating the SMAS in the midfacial region

► Mainstay of SMAS facelift procedures for addressing facial aging in the midface region

■ Retaining ligaments

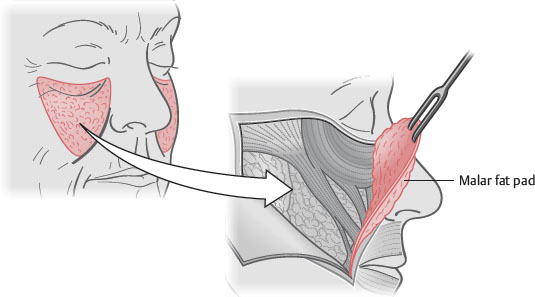

• Midface retaining ligaments20 (Fig. 40-2)

Fig. 40-2 Retaining ligaments of the midface and orbit.

♦ Orbicularis retaining ligament21

♦ Zygomatic ligament

♦ Upper masseteric ligament

■ Nasolabial fold (see Chapter 43)

• Confluence of SMAS, dermis, and muscle fascia overlying muscles of facial expression

• Complex facial anatomic structure

• Prominence adds to aged appearance

• Contributes to midface aging

• Surgical correction is complex and controversial as to the ideal procedure.

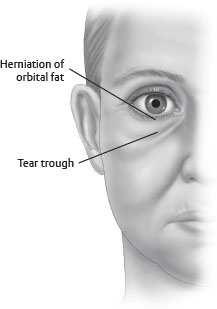

■ Tear trough (see Chapter 37) (Fig. 40-3)

Fig. 40-3 Tear trough.

• Also known as nasojugal groove

• Prominence increases with age

• Medial aspect of the lower eyelid

• Becomes more prominent with loss of cheek volume and descent of midface structures; groove often accentuated by herniated orbital fat

► Anatomic cause of groove is controversial.

♦ Some surgeons think it is the prominence of the orbital rim after descent of the malar fat pad.

♦ Probably is triangular confluence of the inferomedial orbicularis oculi, levator alaeque nasi, and levator labii superioris, which is located inferior to the orbital rim and becomes apparent with volume loss in this area.

■ Muscles

• Orbicularis oculi

► Most affected in midface lift procedures

► Sphincteric muscle originating from the orbital bones and inserting into the soft tissues of the eyelids

TIP: Repositioning the lateral canthus and orbicularis oculi muscle, thus shortening the apparent length of the lower eyelid, is crucial to re-creating a youthful appearance of the periorbital region and midface.

• Zygomaticus major: Important for smiling

► Major anatomic landmark in dissection of midface procedures

• Risorius: Important for smiling

• Levator labii superioris

• Orbicularis oris

• Masseter

■ Skin

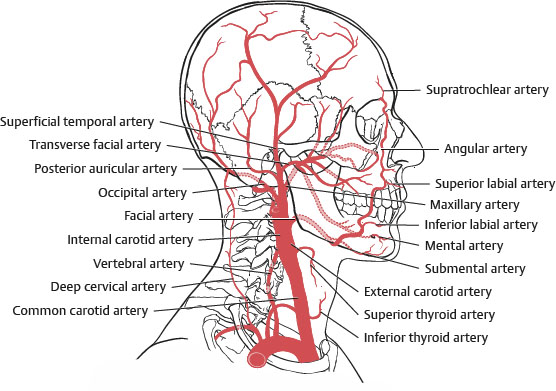

Fig. 40-4 Blood supply.

• Mainly from branches of the external carotid artery

• Significant anastomoses with the internal carotid artery system exist in the periorbital region

• Facial artery

• Infraorbital artery

► Supplies the lower eyelid and midcheek

► May be injured during subperiosteal midface dissection as it exits its foramen

• Superficial temporal artery

► Travels within the SMAS layer as it crosses the zygomatic arch

► Protected in sub-SMAS dissection

• Transverse facial artery

► Supplies lateral canthal region

■ Innervation

• Sensory: Branches of CN V2 (trigeminal)

► Infraorbital nerve

► Zygomaticofacial nerve

► Posterior maxillary nerve

• Motor: Zygomatic and buccal branches of facial nerve (CN VII)

► Orbicularis oculi is predominantly supplied by zygomatic branches that mainly enter near inferior lateral aspect entering on the posterior aspect of the muscle.

► Lower lid receives additional innervation from a buccal branch from the midcheek, which passes deep to the zygomaticus major.

► Additional buccal branches extend medially.

► In general, in midface surgery, injury to a distal branch rarely results in a noticeable deficit.

APPLIED ANATOMY

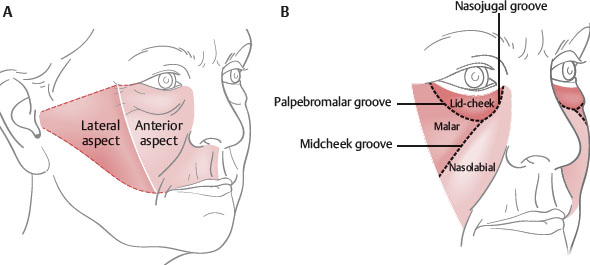

■ The midface is divided into an anterior and a lateral segment.

• Anterior segment is called the midcheek.22

• Midcheek is the portion of the midface on the anterior aspect of the face, extending from the lower eyelid caudally to the nasolabial groove and upper lip22 (Fig. 40-5, A).

Fig. 40-5 Subcutaneous compartments of the midcheek.

• The aesthetically pleasing fullness of the youthful cheek is produced by the midcheek.

■ As a person ages, changes in the midcheek reveal that it comprises three distinct anatomic structures22 (Fig. 40-5, B).

1. Lid-cheek segment

2. Malar segment

3. Nasolabial segment

■ Understanding the influence of each of these structures and the changes affecting each during the aging process is important to adequately correct changes that occur over time.

• As the aging process progresses and affects these three structures, the midcheek segments become separated by three cutaneous grooves.22

1. Palpebromalar groove: superolaterally

2. Nasojugal groove: Medially

3. Midcheek groove: Inferolaterally

■ These three grooves intersect to form an obliquely oriented Y.22

• The midcheek groove runs essentially parallel to the nasolabial fold; cephalically, it extends into the nasojugal groove.

• The palpebromalar groove extends laterally toward the lateral canthus at the cephalic limit of the midcheek.

Changes With Aging

■ Loss of skin elasticity from decreased collagen

■ Epidermal thinning and the development of rhytids

■ Loss of fat volume

■ Descent of soft tissues from attenuation of ligamentous structures, causing the development of prominent grooves and a gaunt look from volume loss

■ Changes in the skeletal support structure of the midface

■ Midface shape defined by specific shape and projection of the orbital bones, zygoma, and maxilla

• May be the most influential factor creating individual variation of facial appearance

■ Studies have shown the changes in the bone structure of the midface with age.

• Pessa et al23 suggested that age-related changes in bone structure led to posterior retrusion of the inferior orbital rim and the anterior maxilla.

• Using facial CT scans to assess midface skeletal changes in male and female patients, Mendelson et al24 found that the angle between the anterior maxilla and the orbital floor decreased in both sexes over time.

• Yet, in contrast to previous reports, Mendelson found that the inferior orbital rim remained relatively fixed. Thus, the retrusion of the anterior maxillary wall in relation to the fixed inferior orbital rim leads to the “negative vector” appearance of the lid-cheek junction, as described by Jelks et al.25

• Shaw and Kahn26 also used CT evaluation to show significant decrease in the glabellar and maxillary angles with increasing age.

• These studies all contrast the earlier notion that facial skeletal aging changes consisted of growth and expansion with advancing age.

• Recent data intuitively make sense, because these skeletal structures serve as the foundation of the midface soft tissues and the site of attachment of the muscles of the lower lid and upper lip and the supporting/retaining ligaments of the midface.

• Pessa et al23 and Mendelson et al24 showed greater changes in maxillary angles in males during aging. The posterior displacement of the anterior maxilla leads to loss of soft tissue support, which, in addition to soft tissue volume loss, accentuates the aging changes in the midface.

• Skeletal support loss could explain the descent of the malar fat pad/soft tissues and their influence on deepening of the nasolabial fold, which is a fixed structure.

Midface Similarities With the Scalp

■ The topographic anatomy of the scalp has been described in five layers:

1. Skin

2. Subcutaneous tissue

3. Musculoaponeurotic layer

4. Loose areolar tissue

5. Fixed periosteum and deep fascia

■ Anatomic structure of the midface can be equated with that of the scalp22 (Fig. 40-6).