Microneurovascular Free Transfer of Pectoralis Minor Muscle for Facial Reanimation

J. K. TERZIS

The pectoralis minor muscle seems to have the best qualities of both the gracilis and extensor digitorum brevis muscles, previous choices for facial reanimation, but without their disadvantages. The pectoralis minor is an ideal shape, has adequate bulk, and possesses a dual nerve supply that allows for independent movements of its upper and lower portions. These characteristics make the muscle a more intelligent choice than either the gracilis or extensor digitorum brevis for substitution of atrophied facial musculature (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

INDICATIONS

The best indication for use of the pectoralis minor muscle flap is in developmental facial paralysis in young children. For use in a 4- or 5-year-old child, the muscle dimensions are ideal (i.e., 6 to 10 cm long and 0.4 to 0.6 cm wide). In these patients, the muscle can be used totally, without thinning or shortening. The muscle also can be an excellent choice for adults, especially patients who are not athletic and have not built up muscles of the upper torso through sports or exercise. Its use is not recommended in well-developed patients, especially weightlifters or swimmers, because of excessive bulk, unless substantial debulking is undertaken.

Donor-site morbidity is minimal, limited to a small incision over the anterior axillary fold, an imperceptible loss of pectoralis major bulk that is not appreciated by the patient but only by careful inspection of the upper thoracic area, and no reportable functional loss.

The muscle is flat and is composed of several slips that can be separated in a distoproximal fashion for a substantial length without fear of vascular and neural compromise. It has

sufficient bulk to substitute for the lower face and can yield adequate excursion in the needed directions of pull. If the hilus of the muscle is placed over the zygomatic arch, its slips of origin can be separated and fashioned to substitute not only for the zygomatic major muscle, but also for the elevators of the upper lip and for the retractors of the commissure. A multidirectional pull can be obtained that is ideal if the patient has a “canine” type of smile in the contralateral normal face.

sufficient bulk to substitute for the lower face and can yield adequate excursion in the needed directions of pull. If the hilus of the muscle is placed over the zygomatic arch, its slips of origin can be separated and fashioned to substitute not only for the zygomatic major muscle, but also for the elevators of the upper lip and for the retractors of the commissure. A multidirectional pull can be obtained that is ideal if the patient has a “canine” type of smile in the contralateral normal face.

Possibly, the most important advantage of the pectoralis minor is its dual innervation, a proof of its segmental origin during development. The upper third of the muscle is innervated by a branch of the lateral pectoral nerve, while the lower two thirds receive nerve supply from the medial pectoral nerve, an offshoot from the medial cord of the brachial plexus. This dual innervation allows for independent movements of the upper part quite separately from the lower part of the muscle. These separately moving muscle subunits can be used to address the separate needs of animation of the eye and mouth, a quality not present in previously described muscle units.

ANATOMY

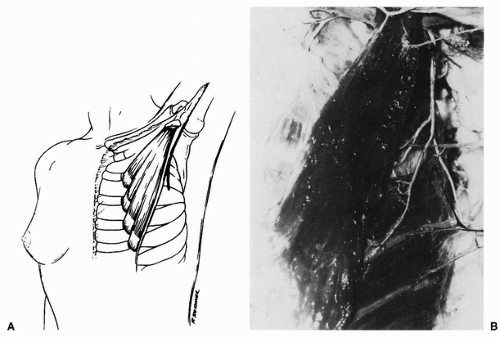

The pectoralis minor is a flat, thin, triangular muscle situated beneath the pectoralis major. The muscle arises from the outer surfaces of the third, fourth, and fifth ribs near their costochondral junctions and from the fasciae covering the intercostal muscles. The fibers ascend upward and laterally and converge to form a flat tendon that inserts in the upper surface of the coracoid process of the scapula. Frequently, there is an additional slip that originates from the second rib.

The normal action of the muscle is pulling the scapula forward and downward, assisting simultaneously in adduction of the arm by rotating the scapula. If the scapula is maintained in a fixed position by the levator scapulae, the pectoralis minor raises the corresponding ribs in forced inspiration.

Blood Supply

There is great variability in the arterial supply of the pectoralis minor, with contributions received from three main sources: the lateral thoracic artery, the thoracoacromial artery, or directly from a branch of the axillary artery. Infrequently, the latter arterial source is present when contributions to the muscle from the other two arterial trunks are minimal. I call this direct artery the “lateral thoracic artery” because, in the few clinical encounters in which a direct artery from the axillary to the pectoralis minor occurred, there was no visible contribution to the muscle from other arterial sources more inferiorly. In the original ten dissections, a separate branch from the axillary artery was never encountered.

By far the predominant vascular pattern is from branches of the lateral thoracic or thoracoacromial arteries. The former passes around the lateral margin of the muscle after it has supplied it with a branch, while the latter passes around the medial margin of the muscle after it has issued an arterial branch, usually to the superior part of the muscle. One or the other branch is dominant, but in a clinical series, the dominant branch came more frequently from the lateral thoracic artery. When the two branches share the blood supply to the pectoralis minor, harvesting the muscle on the lateral thoracic contribution has been the choice, but in these patients, the superior portion of the muscle was not as well perfused and appeared duskier.

There is also extensive variability in the venous drainage of this muscle. More often than not, there is a separate vein that will drain the muscle adequately; however, in many cases, one of the venae comitantes must be used because the direct vein is absent. If there is some doubt about dominant venous drainage, it is best to harvest all the available veins and to observe under magnification which one best drains the muscle unit after microvascular transfer.

Nerve Supply

The nerve supply to the muscle has minimal variations. The majority of the pectoralis minor (four fifths) receives innervation from the medial pectoral nerve, while the most superior part of the muscle receives a tiny branch from the lateral pectoral nerve. Another substantial branch of the lateral pectoral nerve destined to innervate the pectoralis major uses the pectoralis minor only as a passway; thus harvesting the pectoralis minor necessitates taking of that nerve. However, these axons need not be lost, and if time is taken to redirect these fibers back to the pectoralis minor, additional innervation can be obtained through a process of direct neurotization.

The nerve supply to the pectoralis minor is multisegmental, receiving contributions from all five spinal nerves contributing to the brachial plexus, namely, C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1. Motor fibers from these spinal nerves reach the pectoralis minor through branches of two nerves, the lateral and medial pectoral nerves. The dominant innervation to the pectoralis minor is through the medial pectoral nerve, with contributions from C8 and T1. A major branch from this nerve is responsible in all cases for three fourths or two thirds of the muscle, depending on whether the muscle has three or four slips. Also constant is the innervation of the superior part of the pectoralis minor, which, in all cases, comes through a tiny branch from the lateral pectoral nerve. A larger lateral pectoral branch also penetrates the muscle, but it usually does not supply the muscle; instead, it courses through it on its way to the pectoralis major.

Contrary to reported variability in the nerve supply of the pectoralis major, the innervation of the pectoralis minor is relatively constant. Variations are limited to the presence or absence of the communicating loop, with fiber exchange between the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. It is worth mentioning that in two clinical cases of severe brachial plexopathy, with documented neuroradiologic and electrical findings of C8 and T1 avulsion, the inferior segment of the pectoralis minor responded to intraoperative electrical stimulation, raising the possibility that some motor fibers from T2 may contribute to the innervation of this muscle.

The dual innervation of the pectoralis minor makes it a unique muscle for facial reanimation procedures because the upper leaves can be motored separately from the lower portion of the muscle. This characteristic opens possibilities for independent eye and mouth movements, one of the greatest advantages of using this muscle for facial-muscle substitution (Figs. 157.1, 157.2, 157.3, 157.4).

FLAP DESIGN AND DIMENSIONS

In the adult, the individual slips of the muscle measure 10 to 14 cm long. The upper leaves are shorter, and the lower leaves are longer. In a child or baby, pectoralis minor leaflets are only 6 to 10 cm long, making it ideal for facial reanimation procedures, since the muscle can be used in toto without any trimming. The width of the muscle is less than 0.5 cm in very young patients, but it can be up to 2 or 3 cm in athletic adults, a situation that would require extensive debulking.

FIGURE 157.1 A: The location of the pectoralis minor on the anterior thorax showing the four slips of origin near the costal cartilages and the coracoid tendinous insertion. Note the heavy line over the anterior axillary fold, which signifies the incision for microsurgical harvesting of this muscle. B: Corresponding fresh dissection specimen showing the pectoralis minor exposed after removal of the pectoralis major muscle. (From Terzis, ref. 7, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|