Figure 36-1 Metastatic carcinoma of stomach origin to the face. Multiple dermal and subcutaneous nodules are seen on the face and neck.

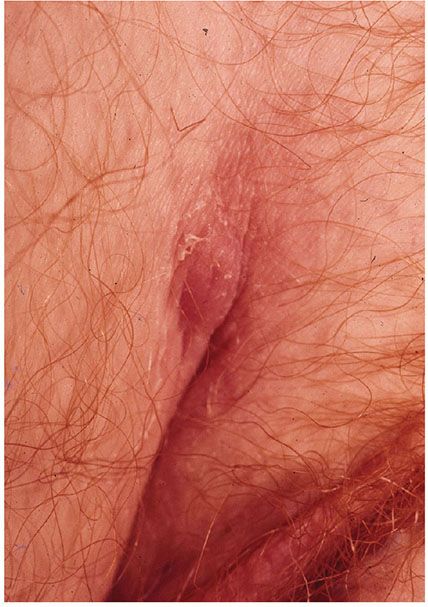

Distinction of a primary carcinoma of the skin from a metastatic lesion can be a problem when dealing with a solitary lesion (Fig. 36-2). Some examples include primary mucinous adenocarcinoma of skin (20–22), adenocarcinoma of the mammary-like glands of the vulva (23), cutaneous signet-ring carcinoma (24), primary carcinoids (25,26), and adnexal carcinomas (27).

Figure 36-2 Metastatic ovarian carcinoma to the inguinal area. A single nodule of recent onset.

To establish a diagnosis of a primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin, the presence of a peripheral myoepithelial layer, if present, is helpful (21). Immunoperoxidase positivity with CD15, CK5/6, and 34BE12 (22) favor a primary lesion. A number of studies have shown that p63 staining of a tumor favors a primary tumor over a metastatic lesion (27–29). Other markers favoring a primary skin cancer include CK15, D2-40, and nestin (4,7,12). Except for sebaceous tumors, there is rare reactivity for primary adnexal carcinoma of the skin with CD10 in comparison with metastatic carcinoma, especially metastatic renal cell carcinoma (30).

Although metastatic lesions can occur at any site, the scalp, head, and umbilicus are more frequent. Finding of the primary tumor or the presence of serum chromogranin (25) would indicate a metastatic carcinoid.

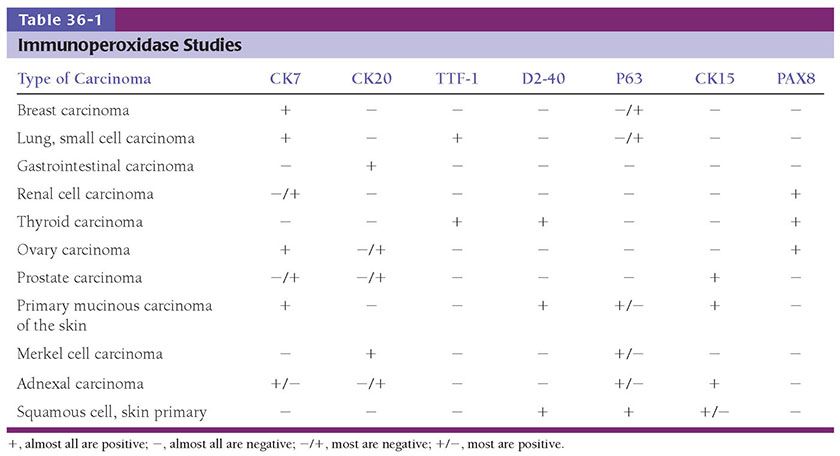

Some immunoperoxidase stains that are helpful in distinguishing primary tumors from metastatic lesions are shown in Table 36-1.

Molecular approaches for identification of tissue can also be used, but is not the subject of this chapter (31,32).

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT FOR CUTANEOUS METASTASES

The management of cutaneous metastases has been recently reviewed from a dermatologic perspective (33). Adiagnosis of a cutaneous metastasis should prompt an assessment for the presence of distant disease and the total tumor burden, which will guide subsequent therapy. Excision of metastases is recommended when surgically feasible and when this will result in a significant decrease in total tumor burden, improve quality of life, or result in increased functionality.

Using melanoma as an example, isolated metastases may be excised with up to a 1-cm margin of normal skin, although there are no evidence-based studies of the utility of margins for metastatic disease. More limited excisions may be performed for palliation and when there are cosmetic or functional considerations. Options for therapy for patients with widespread cutaneous and subcutaneous metastases of advanced melanoma that are nonresectable include radiotherapy, isolated limb perfusion, interferon alfa injections, cryotherapy, laser ablation, or radiofrequency ablation, and for patients with disseminated disease, systemic chemotherapy, oncogene-targeted therapy, and immunotherapy.

Sometimes, treatment of the primary cancer with a successful regimen will cause cutaneous lesions to lessen. For example, an abscopal response represents an unusual response to radiation therapy in which radiation of a tumor causes untreated distant skin lesions to dissipate without recurrence. The abscopal response has been reported with treatment of melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and hematologic, and solid tumors, and may be caused by activated cellular immunity (33).

Novel treatments have had a profound effect on prolonging the survival and improving the quality of life with metastatic cancer. Oncogene-targeted therapy represents a potential revolution, though its benefits so far are limited for most patients. In general, tumors newly presenting with metastatic disease should be submitted for oncogenic mutation testing, which increasingly is done using large panels of genes. Appropriate targeted therapy for metastatic melanoma associated with a mutation of the BRAF gene results in complete or partial tumor regression in the majority of patients, with an estimated median progression-free survival of more than 7 months (33). Current trials emphasize the use of agents targeting more than one oncogene (e.g., BRAF plus MEK inhibitors), in the hope of extending survival.

Another promising mode of therapy for patients with disseminated metastatic disease is the use of agents that modify the host immune response. Examples include the use of immune check point inhibitors such as ipilimumab, and monoclonal antibodies directed at the programmed death 1 (PD-1) protein or its ligand. In the near future, use of these agents in various combinations with targeted therapy and other modalities likely will result in improved survival for patients with metastatic melanoma, and for other cancers as well.

CARCINOMA OF THE BREAST

Cutaneous metastases that occur predominantly by lymphatic dissemination include inflammatory carcinoma, carcinoma en cuirasse, telangiectatic and nodular carcinoma, and carcinoma of the inframammary crease. Alopecia neoplastica and mammary carcinoma of the eyelid are probably caused by hematogenous spread (13).

Clinical Summary. Inflammatory breast carcinoma is characterized by an erythematous patch or plaque with an active spreading border that resembles erysipelas and usually affects the breast and nearby skin (13). Rarely, inflammatory metastatic carcinoma may arise from primary involvement of other organs. The inflammatory appearance and warmth are attributed to capillary congestion.

En cuirasse metastatic carcinoma is characterized by a diffuse morphea-like induration of the skin and rarely involves skin from other primary carcinomas. It usually begins as scattered papular lesions coalescing into a sclerodermoid plaque without inflammatory changes.

Telangiectatic metastatic breast carcinoma is characterized by violaceous papulovesicles resembling lymphangioma circumscriptum (13). A violaceous hue, which is often present, is caused by blood in dilated vascular channels.

The nodular form appears as multiple firm nodules that may show ulceration. An exophytic nodule may occur in the inframammary crease resembling a primary squamous cell or basal cell carcinoma and occurs more frequently in women with large breasts.

Alopecia neoplastica occurs as oval plaques or patches of the scalp and may be confused clinically with alopecia areata or a scarring alopecia. Metastatic mammary carcinoma in the eyelid clinically presents as a painless swelling with induration or as a discrete nodule (13). Of 10 metastatic tumors to the eyelids, 4 were breast carcinomas, 2 were renal, and 1 each were thyroid, prostate, lung, and salivary gland (34).

Histopathology. In inflammatory carcinoma, histologic examination of the skin reveals extensive invasion of the dermal and often the subcutaneous lymphatics by groups and cords of tumor cells. The tumor cells are similar to those in the primary growth and atypical in character with large, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei. There is marked capillary congestion, which is the reason for the clinical appearance of erythema and warmth (13). Often, there is interstitial edema and a slight perivascular lymphoid infiltrate. The extensive lymphatic dissemination is caused by retrograde lymphatic spread into the skin secondary to blockage of the deep lymphatics and lymph nodes. Fibrosis is not a significant feature. Some studies indicate that only 1% to 4% of patients with metastatic breast carcinoma present with the inflammatory or erysipeloid type and that most of these patients have intraductal breast carcinoma (35).

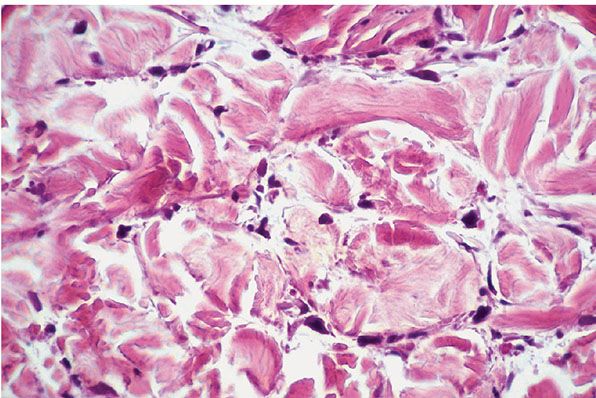

In carcinoma en cuirasse, also referred to as scirrhous carcinoma, the indurated areas show fibrosis and may contain only a few tumor cells. The tumor cells may be confused with fibroblasts. The tumor cells have elongated nuclei similar to fibroblasts, but the nuclei are larger, more angular, and more deeply basophilic. The tumor cells often lie singly; however, in some areas, they may form small groups or single rows between fibrotic and thickened collagen bundles (Fig. 36-3). This latter feature of “Indian filing” is of particular diagnostic importance and may be seen in any histologic variety.

Figure 36-3 Metastatic breast carcinoma. Individual atypical tumor cells are seen between fibrotic collagen bundles.

In telangiectatic carcinoma, the tumor cells tend to be located more superficially in the dermis within dilated lymphatic vessels than those in inflammatory carcinoma. The blood vessels are congested with red blood cells, as in inflammatory carcinoma, but usually also contain aggregates of neoplastic cells. The presence of many dilated blood vessels immediately beneath the epidermis gives rise to the clinical appearance of hemorrhagic vesicles.

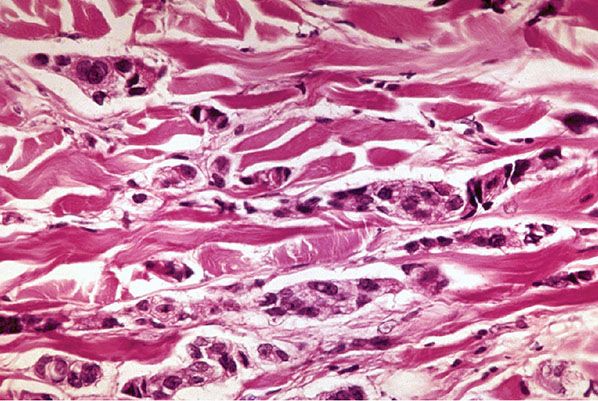

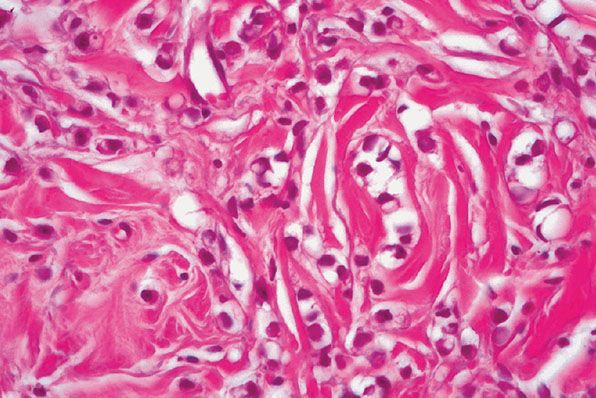

In nodular carcinoma, there are variably sized groups of tumor cells in the dermis, and these nodular areas are surrounded by fibrosis. Depending on the tumor type, some cells may show a glandular arrangement, which may be quite ill-defined (Fig. 36-4). Sometimes, a nodule may be pigmented and clinically suggestive of a melanoma or pigmented basal cell carcinoma. The pigment results from melanin accumulation within the cytoplasm of neoplastic cells and in the stroma (36).

Figure 36-4 Metastatic breast carcinoma. Cords of atypical cells with ill-defined attempts at acinus formation infiltrating between collagen bundles.

Carcinoma of the inframammary crease has been described as islands of epithelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei extending contiguously with the epidermis from the dermis (37).

In hematogenous metastases, the histologic picture varies with clinical presentation. In alopecia neoplastica, the features resemble those of the en cuirasse type, with single files of tumor cells between thickened collagen bundles. Metastatic mammary carcinoma involving the eyelid has been described in 13 patients, and in 8 of them, the microscopic features had a prominent histiocytoid appearance (38).

Epidermotropic involvement from metastatic breast carcinoma may mimic malignant melanoma and/or Paget disease (39).

The signet-ring cell histologic pattern of breast carcinoma (Fig. 36-5) may also be seen in carcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract and urinary bladder (40). This may be confused with a primary cutaneous signet-ring cell carcinoma that occurs most frequently in middle-aged men on the eyelid and less frequently in the axilla (40). A primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin also may require distinction from metastatic lesions from the breast or colon (15). Rarely, a granular cell histologic pattern is seen.

Figure 36-5 Metastatic breast carcinoma. This tumor demonstrates a signet-ring cell pattern.

Immunoperoxidase Studies. Cutaneous metastases of mammary carcinoma are positive with most cytokeratins, except for CK20 (15), and often are positive with epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Reactivity with S-100 protein has been reported in cases of primary and metastatic breast carcinoma (41). The presence of melanin granules and melanosomes within tumor cells that give a positive HMB-45 is rare and probably occurs secondarily to phagocytosis or melanocyte colonization of the tumor cells (29). In lesions in which there are cells positive with S-100 or HMB-45, strong reactivity with keratins or reactivity with EMA and/or CEA would rule out melanoma. A positive androgen receptor marker might be helpful in supporting metastatic breast cancer when estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors are negative. Primary signet-ring carcinoma of the skin has been reported to be positive with CK7 and CK20, and this would aid in distinction from the breast, which is usually negative with CK20 (40). Most breast carcinomas are negative with D2-40, nestin, and CK15, but a subset showed 5% positive with CK15 (42,43).

Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, which is generally thought to derive from the sweat glands, is positive with numerous cytokeratins but is negative with CK20. This would allow distinction from a metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon, which would be positive with CK20 (44).

Expression of CK7 was found in the majority of cases of carcinoma, with the exception of those arising from the colon, prostate, kidney, thymus, carcinoid tumors of the lung and gastrointestinal tract, and Merkel cell tumors of the skin.

CARCINOMA OF THE LUNG

Metastasis to the skin is more common in men, but the incidence of lung carcinoma in women is increasing (5,6). In 56 patients reported with skin metastasis from lung carcinoma, 7% had a skin nodule before the diagnosis of the primary tumor, and 16% had a nodule at the same time (45). In 11 of 21 patients with cutaneous metastasis, the skin was the first extranodal site (1).

Clinical Summary. Metastases may occur on any cutaneous surface, but the most common sites are the chest wall and posterior abdomen (13). Small cell carcinoma shows predilection for the skin of the back (2). Most lesions present as a localized cluster of cutaneous papules or nodules or as a solitary nodule.

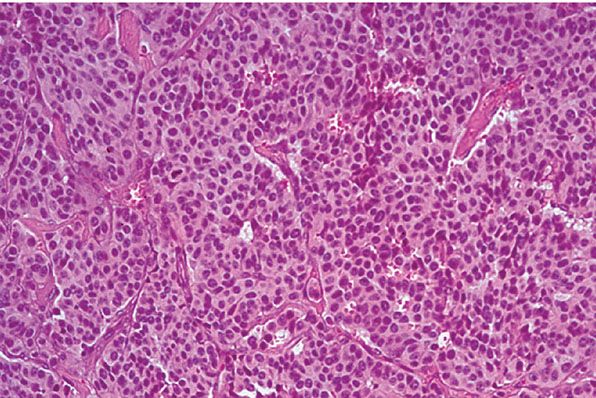

Histopathology. Cutaneous metastases were undifferentiated in approximately 40% and adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in approximately 30% each (4). The undifferentiated tumors were often of the small cell type with hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm, formerly known as oat cell carcinomas (4). Carcinoid tumors of the lung are derived from the bronchus and consist of solid islands and nests of uniform cells (Fig. 36-6). Other sources of carcinoid tumors include the stomach, small and large intestines, and primarily the skin (46,47). The closely packed tumor cells may suggest a malignant lymphoma. Immunoperoxidase studies are extremely helpful in making this distinction. Larger cells require consideration of metastatic amelanotic melanoma and, again, immunoperoxidase studies may be required for distinction.

Figure 36-6 Metastatic carcinoid tumor from the lung. Uniform small cells without high-grade atypia, forming nests in a typical pattern of a carcinoid tumor.

Squamous cell carcinomas that are metastatic to skin are usually poorly or moderately differentiated (4). They can usually be distinguished from primary squamous cell carcinoma by the absence of proliferation from the surface epidermis and seldom show an orderly pattern of differentiation from basaloid to prickle cells with centers of keratinization. They may show occasional whorls of squamoid cells with imperfect keratinization and individually keratinized cells, and sometimes have large, bizarre forms with frequent mitotic figures (4). In larger tumors, areas of central necrosis are often present. Most cutaneous metastatic squamous cell carcinomas arise in the lung, oral cavity, or esophagus. Tumors from the oral cavity tend to be more differentiated and nearly always appear on the head or neck. Squamous carcinoma metastatic from the esophagus shows essentially similar features to that from the lung (4).

Adenocarcinomas metastatic to the skin from the lung are often moderately differentiated, but some show well-formed, mucin-secreting, glandular structures. Individual tumor cells sometimes contain abundant cytoplasmic mucin but usually lack large pools of mucin, which is more characteristically seen from gastrointestinal metastatic adenocarcinomas (4).

Immunoperoxidase Studies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree