Fig. 8.1

Operative steps. (a) Preoperative markings: Red line represents the incision, blue infraumbilical rectangle represents area of full-thickness excision, green lateral triangles represents areas of supra-Scarpa’s fascia excision, indigo supraumbilical triangle represents area of dissection to enable midline plication, yellow small triangles represents areas of Scarpa’s fascia excision, violet area represents area of liposuction. (b) Infraumbilical midline full-thickness excision. (c) Lateral supra-Scarpa’s excision. (d) Scarpa’s fascia pulled medially and sutured in the midline, causing traction on Scarpa’s fascia in the waist area, leading to improved waistline definition

Fig. 8.2

(a) Upper and lower incisions and the midline strip of tissues to be excised full thickness down to the musculoaponeurotic layer. (b) Lateral skin and supra-Scarpa’s fat excised using the Harmonic scalpel. The white Scarpa’s fascia is evident below the tip of the Harmonic scalpel

Fig. 8.3

(a) Limited dissection of abdominal flap in the midline. A triangular excision of the Scarpa’s fascia is done at its junction with the abdominal wall (yellow dotted triangles) to prevent central bulging with midline closure of infraumbilical Scarpa’s fascia. (b) Full-thickness excision “midline” and supra-Scarpa’s excision “lateral” with triangular Scarpa’s fascia at supermedial angles (yellow dotted triangles)

Fig. 8.4

(a, b) Well-defined Scarpa’s fascia layer. (c) Tightening of the flanks with medial advancement of Scarpa’s fascial layer towards midline

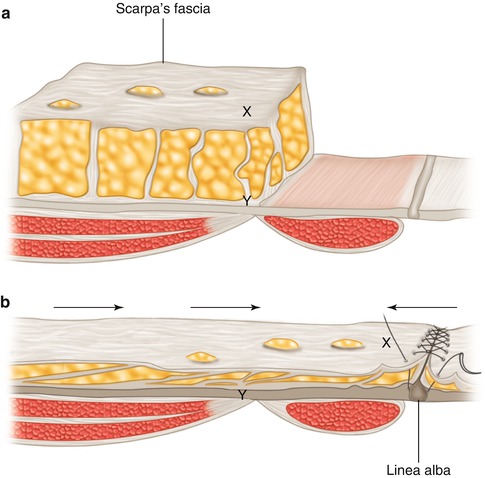

Fig. 8.5

(a) The preserved Scarpa’s fascia and underlying fat lateral to the midline. Note X and Y are two points on the same vertical plane. (b) The Scarpa’s fascia is pulled medially and sutured to its counterpart in the midline. The Scarpa’s fascia glides medially over the underlying fat (horizontal arrows); note the medial transposition of point X, while point Y is fixed to the abdominal wall

8.4.2 Results

During the period from January 2008 till March 2012, the authors of this work performed the “Brazilian” abdominoplasty technique in 87 patients. All patients were females except for 1 male patient. The patients’ ages ranged from 27 to 69 years (mean age 47 years). Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative photographs were taken. The follow-up period ranged from 2 months to 3 years. The overall complication rates were extremely low (4.5 %), with only one hematoma (1.14 %) (in a massive weight loss patient) requiring surgical evacuation. No seromas required drainage in this series, and the only wound problem was with a “V-loc” suture sinus (1.14 %) that resolved on conservative management. Two cases required revisional surgery for liposuction centrally and for a further skin excision (2.2 %). Patients reported high satisfaction with postoperative improvement in waist definition. Pre- and postoperative photographs demonstrated significant improvement of waist definition (Figs. 8.6, 8.7, 8.8, 8.9, 8.10, and 8.11)

Fig. 8.6

(a) Preoperative 44-year-old lady requesting abdominoplasty procedure. (b) Six months postoperative after Brazilian abdominoplasty showing significant improvement of waist definition

Fig. 8.7

(a) Preoperative 37-year-old lady. Note the loss of waist definition. (b) Three months postoperative after Brazilian abdominoplasty showing improvement of waist definition

Fig. 8.8

(a) Preoperative 40-year-old lady requesting abdominoplasty. (b) Six months postoperative after Brazilian abdominoplasty showing improvement of waist definition

Fig. 8.9

(a) Preoperative 38-year-old lady with loss of waist definition. (b) Three months postoperative after Brazilian abdominoplasty showing improvement of waist definition

Fig. 8.10

(a) Preoperative 45-year-old lady requesting abdominoplasty. (b) Six months postoperative after Brazilian abdominoplasty showing significant improvement of waist definition

Fig. 8.11

(a) Preoperative 43-year-old lady requesting abdominoplasty. (b) Two years postoperative after Brazilian abdominoplasty showing improvement of waist definition

8.5 Discussion

It appears that the distribution and not the absolute levels of body fat that is most important in determining female attractiveness. This explains the importance of restoring waist definition. Singh in his investigation of temporal changes in absolute levels of body fat for beauty pageant contestants showed that despite temporally dependent changes in beauty ideals, the preferred ideal waist-to-hip ratio has stayed roughly the same at 0.7 [18].

Many techniques have been proposed to correct truncal contour deformities, especially those involving the waist area. Some of these techniques addressed the musculoaponeurotic layer of the abdomen. Psillakis [19] sutured bilateral external oblique muscles to the rectus sheath, thereby reducing the diameter of the waist. Later he modified his technique by dissecting the external oblique muscles and resuturing them in the midline, together with resecting cartilage from the 7th and 8th ribs to reduce the diameter of the upper abdomen in case of exaggerated anterior projection [20]. Although the author did not comment on the complication rate with that technique, we believe that the extensive dissection and rib resections carry a higher rate of complications. Jackson et al. [21] describe the waistline suture. After vertical midline plication, a horizontal fascial plication at the level of the umbilicus was accomplished to reduce further the resultant vertical fascial excess. Posterior rectus fascia plication with concomitant rectus muscle excision to treat severe diastasis has been described by de Pina [22]. Abramo et al. [23] proposed a combination of two horizontal plications of the musculoaponeurotic layer at the top and bottom of the vertical plication, thus creating an H-shaped pattern of plication. The horizontal plication not only minimized the musculoaponeurotic laxity but also brought the cutaneous flap downwards minimizing the tension on skin closure. Marques et al. [24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree