Fig. 14.1

Histological section of the skin from the epigastrium stained with hematoxylin and eosin showing a smaller amount of collagen fibers (arrows) in patients after morbid obesity. (a) Control group patient. (b) Patient after massive weight loss

Fig. 14.2

(a, b) Examples of patients after massive weight loss

In these situations, patients turn to plastic surgery to obtain a more harmonious body contour and minimize or cure the collateral problems that accompany dysmorphism. As a rule, these patients request abdominoplasty as the first surgical intervention for the treatment of their abdominal deformity [4].

Abdominoplasty techniques may be performed using a transverse (classic), vertical, or anchor-line (“Fleur-de-Lis”) incision (Fig. 14.3). After classic abdominoplasty is performed in patients with significant excess skin and fat, some of this excess frequently remain in the lateral areas. This implies extension of the incisions to the flanks, thus defining the procedure known as flankplasty [5]. As a natural sequence of flankplasty, the incisions are extended to the midline of the back with the purpose of improving the abdominal contour and lifting the buttocks, a procedure that characterizes circumferential abdominoplasty, or belt lipectomy. Not infrequently, patients with this dysmorphism show skin and fat accumulation in the epigastrium and periumbilical region, whose treatment implies vertical fusiform excision associated with the transversal incision similar to an anchor that characterizes the composite circumferential abdominoplasty.

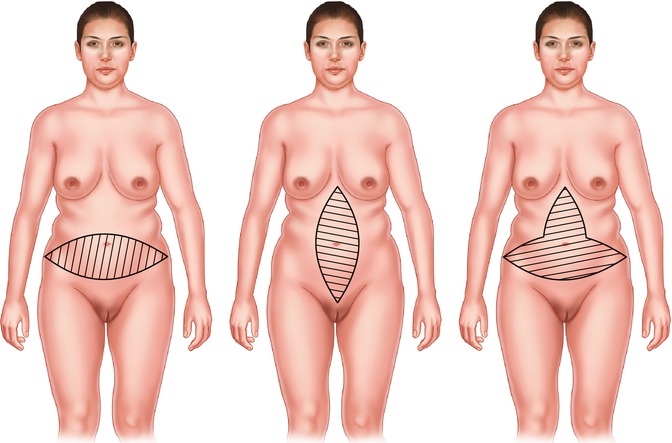

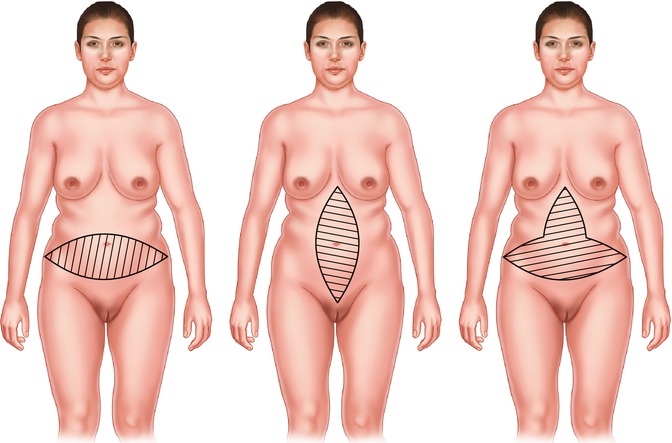

Fig. 14.3

Types of abdominoplasties. (Left) Classic transverse. (Middle) Vertical. (Right) Transverse vertical or “anchor line”

14.2 Background

Abdominoplasty involving the entire abdominal circumference was first described in 1940 by Somalo, who called it circumferential trunk dermolipectomy [6]. In 1961, Gonzales-Ulloa [7] described belt lipectomy, i.e., lipectomy of the lateral region of the abdomen. Because of their extensive incisions, these techniques were forgotten for many years.

Abdominoplasties using transverse incisions were undoubtedly standardized by Callia [8], in 1965, and Pitanguy [9], in 1967. These techniques differ from each other as regards the marking of the lower incision and, consequently, the final scar. Nonetheless, when applied to large abdomens, both would lead to the lateral “dog-ear” deformity. This motivated Baroudi [5] to extend the resection to the flanks, thus defining flankplasty, as published in 1991.

Dissatisfied with the results obtained from conventional abdominoplasties, in 1997, Carwell and Horton [10] described circumferential torsoplasty with the purpose of correcting the residual flank deformities and lifting the buttocks and trochanteric region. This was a landmark in the technique of circumferential abdominoplasty because, although they had treated only a few cases, the authors described the surgical markings in details.

In 2002, Pascal and Louam [11] described an effective procedure for the treatment of the entire abdominal circumference, combining it with a flap to enhance the buttock size. According to the authors, the operative time was long and fatiguing; however, the technique provided favorable results.

In 2003, Modolin et al. [12] reported a surgical procedure called circumferential abdominoplasty, based on Carwell and Pascal’s studies, with modifications. The technique was proposed for post-bariatric patients and stressed the remarkable improvement of patient quality of life.

Also in 2003, Hurwitz [13] carried out a retrospective analysis of patients with massive weight loss who had undergone several procedures in different surgical stages. The author focused on lower body lift, which consists of the combination of circumferential abdominoplasty with thigh lift. In another procedure described as upper body lift, the author associated reverse abdominoplasty in the entire thoracic circumference with mammoplasty and brachioplasty. In some carefully selected cases, he combined upper body lift with lower body lift and concluded that this combination was an advance in the treatment of body contouring, provided that performed by an experienced team.

In all these procedures, the different authors established that excisions should be made zwithout tension to prevent dehiscence by excessive traction and necrosis.

As of 1991, Lockwood [2] stresses the importance of the superficial fascia as a support element. Thus, suturing the superficial fascia of one flap to that of the other ensures the support of structures and the reduction of tension on the resulting scar.

14.3 Anatomy

The abdomen is the part of the trunk that lies between the thorax and the pelvis. Its upper limits are the lower ribs and the xiphoid process; inferiorly, it is limited by the pubis and the inguinal folds; its lateral limits correspond to the midaxillary lines.

The blood supply of the abdominal skin is provided by a rich anastomotic network that originates from the superior and inferior epigastric vessels, with participation of the intercostal, lumbar, and musculophrenic arteries. The lymphatic drainage is divided into two sets: the supraumbilical, which drains upward into the axillary lymph nodes, and the infraumbilical, which drains downward into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

The innervation of the abdominal wall is derived from the intercostal, iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal nerves. The intercostal nerves – from the seventh to the 11th – divide into lateral and anterior branches, which innervate skin strips corresponding to the embryonic metameres. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves are branches of the first lumbar nerve or 12th thoracic nerve and supply the infraumbilical and genital regions, as well as the thigh roots.

The abdominal skin has fixed zones of adherence even after massive weight changes, and these are important references for abdominal surgeries. Thus, a middle line, the linea alba, which extends from the xiphoid process to the pubis passing through the umbilicus, corresponds deeply to the fusion line of the aponeuroses of the anterior rectus abdominis muscles in the midline. It is usually easier to distinguish the linea alba in the upper abdomen, midway between the xiphoid process and the umbilicus, because of the greater fat accumulation in the lower abdomen. Sometimes, superficial to the linea alba, there is a sulcus which is regarded as a beauty standard today.

From the anterior superior iliac crests, going along the inguinal folds and over the upper border of the pubis, lies the inferior abdominal fold, which is more or less pronounced depending on the abdominal fat accumulation. Naturally, this sulcus is virtual in lean individuals, whereas in those with some abdominal fat accumulation, it can be clearly identified.

In the intersection between the midline and the line passing through the inferior border of the last floating rib lies the umbilicus. Some authors also situate the umbilicus in the intersection between the midline of the abdomen and the cross-sectional line tangential to the iliac crests. Anyway, the umbilicus may vary in position as a function of obesity, muscle tone, or pregnancy. On the other hand, since the female abdomen is more round and proportionally longer than males, the distance between the umbilicus and the female genitalia is longer.

14.4 The Ideal Abdomen

Some authors describe the female navel as being more deeply recessed than men’s. As to shape, the issue is controversial, seeing that navels have been described as horizontal, vertical, protruding, concave, and circular. In a recent comparative study, the great majority of full-figured women who were symbols of beauty during the Renaissance had circular navels, while the navels of contemporary female models are shaped like vertical rifts; nevertheless, the shape of the navel is determined by body posture even in the case of thin models.

The abdomen is an important part of the body in any culture. It is, in and of itself, one of the most erotically appealing areas of the male and female anatomy.

The Western culture’s perfect beauty ideal as applied to the abdomen, as well as to the entire human body, has undergone changes in consequence of religious, cultural, and ethnic standards. Artistic representations have been subject to mythic, symbolic, and religious influences right up until today’s prevailing standards.

Hence, the figurine named Venus of Willendorf with ample bosom and a ripe belly that survived the Neolithic period in Europe (35,000–40,000 B.C.) Supposedly, such beauty traits were associated with fertility (Fig. 14.4). Other representations from this same period were also found in Europe and convey admiration for the fecundity of nature as a result of large and protruding abdomens.

Fig. 14.4

Venus of Willendorf (Museum of Natural History, Vienna)

The Egyptian culture did not show much interest in the shapes of the abdomen since, given the religious influence, artistic tendencies aimed at synthesizing the figure of the pharaoh and the zoomorphic gods. However, there is a small statue carved in hippopotamus’ bone, dating back to the period of Nagada I (4,000–3,500 B.C.), which is considered a point of reference for the Renaissance period; its belly is smoothly rounded with a circular penetrating navel (Fig. 14.5).

Fig. 14.5

Statue from the Nagada I period (British Museum, London)

The Greek civilization constituted the foundation of Western cultures and placed man in the center of the universe. Gods and men emulated one another, giving rise to philosophical beauty standards. Greek plastic artists, particularly sculptors, prized the well-balanced shape of a smoothly rounded abdomen, with a longitudinal or circular navel according to the then accepted standards of what was beautiful and desirable. Good examples of these manifestations are the Venus of Cnidus (360 B.C.) (Fig. 14.6) and the Venus de Milo (130 B.C.) (Fig. 14.7) sculpted, respectively, by Praxiteles and Alexandros of Antioch.

Fig. 14.6

Copy of the Aphrodite of Knidos (Vatican Museum – copy faithful to the original, which was lost in a fire in Constantinople)

Fig. 14.7

Venus de Milo (Louvre Museum)

As Greek art continued into the Roman Empire, no important changes in beauty standards took place. During the Middle Ages, also referred to as the Dark Ages, due to religious influence, there is no exposure of the human body, which is represented schematically without any consideration for shape and thus beauty. At the end of the medieval period, representations of the human body emerged, although still distorted by religious prejudice. At the time, paintings by some Flemish artists paid tribute to women with spherical abdomens while featuring a rachitic rosary under the skin of the rib cage. It was a time when Europe underwent a long period of famine, even though the importance of fecundity still prevailed.

During the Renaissance, between the 14th and 17th centuries, the classical humanistic influence resurfaces, represented by the blossoming of the arts and the beginnings of modern science. The great masters of painting retrieved the values and the beauty standards established by the Greeks and the Romans. There was significant appreciation of male body shapes, since female body shapes were not considered perfect. Consequently, the female body was represented either as muscular or as obese when compared to today’s standards. In the latter case, it meant fertility associated with opulence, as opposed to the periods of famine and hardship of the previous medieval period. A good example is Rubens’ uniquely beautiful “The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus” featuring young girls with bulging bellies in gracious motion (Fig. 14.8).

Fig. 14.8

The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (Old Pinakothek, Munich)

As of the eighteenth century, the female body is more realistically conceived; it is elongated, with harmonious and well-balanced curves. At the end of the century, representations of women distance themselves from romanticism, and nudes are closer to reality. Subsequently, at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century, there were new artists who, unlike conventional portrait painters, came up with intriguing propositions that kindled the viewer’s imagination, marking the beginning of the so-called modern art, which detaches itself from the classical ideals of beauty (Fig. 14.9).

Fig. 14.9

Works of nude art. (a) Picasso. (b) Botero

In the twentieth century, with the arrival of TV and sophisticated technical photography resources, the current universally accepted beauty standards identifying a proportional relationship between age and beauty were reached. There are no mathematical or statistical rules that establish a golden ratio or define beauty (Fig. 14.10).

Fig. 14.10

Current beauty standard for a female abdomen

Such reflections highlight the abdomen that at present, in the twenty-first century, has acquired a very important esthetic as well as erogenous significance. Current fashion exposes and values this body part. The navel enhances the erotic abdominal image, sometimes even with the help of ornaments such as belly button piercings.

The incidence of patients with massive weight loss after treatment of morbid obesity has increased exponentially in the past few years. For them, abdominoplasty is the surgery most frequently required. It is known that the satisfaction of these patients is directly related to the body extent treated, i.e., the larger the area with reestablished body contour, the greater the patient satisfaction. For this reason, circumferential abdominoplasty, which treats the entire abdominal circumference and lifts the lateral aspect of the thighs and gluteal region, usually provides patients with great satisfaction [16, 17].

14.5 Patient Selection

Patients selected for circumferential abdominoplasty should present with excess skin and fat in the upper, lateral, and posterior abdomen. In addition, gluteal ptosis with or without the need for gluteal augmentation is also a key factor for the indication of this technique. The excess skin and fat in the epigastrium and the presence or absence of a scar resulting from conventional gastroplasty should also be quantified, because this is determinant for the indication of simple or composite circumferential abdominoplasty [18].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree