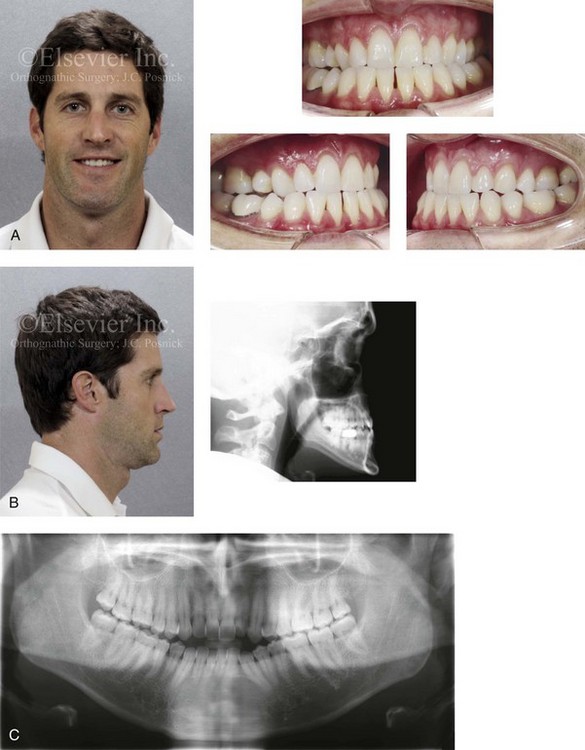

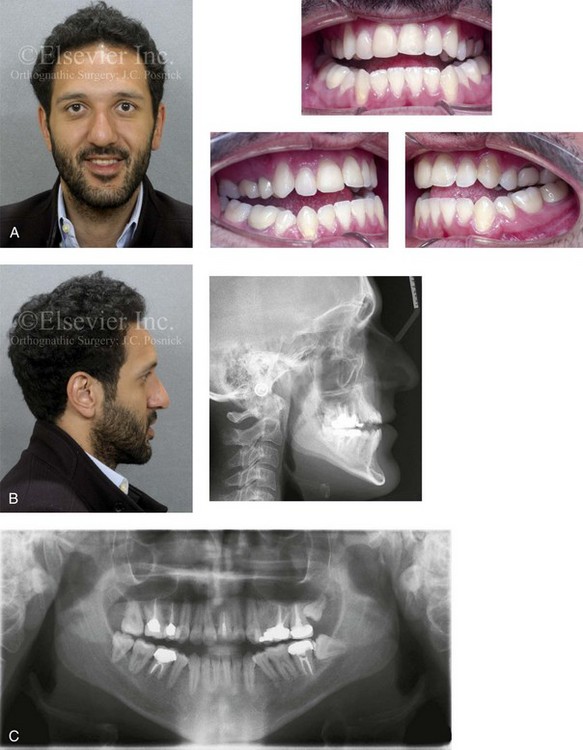

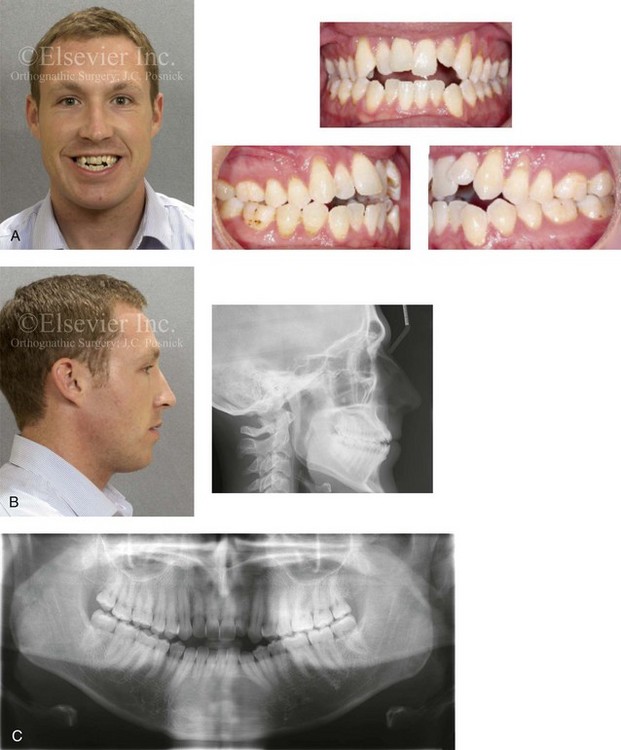

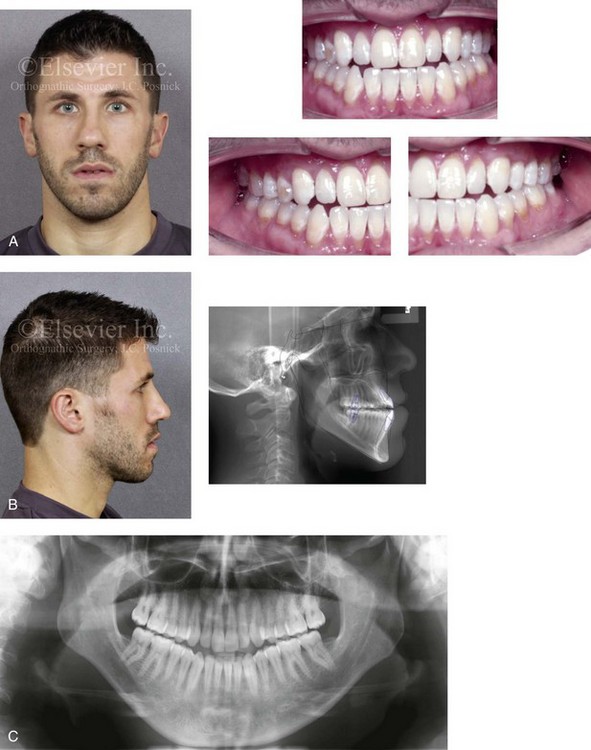

20 • The Role of Growth Modification in the Preadolescent Patient • Orthodontic Camouflage Approach • Surgical Camouflage Approach • Postsurgical Orthodontic Maintenance and Detailing • Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education • Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery • Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery • Suboptimal Facial Aesthetics after Orthognathic Surgery Developmental Class III skeletal problems generally result from maxillary deficiency in combination with relative mandibular excess. Through trial and error, it is now recognized that either growth modification in the preadolescent patient or camouflage treatment in the teenager or adult as a method of managing this type of dentofacial deformity is at best relatively ineffective. In addition, even mild degrees of a Class III facial appearance are aesthetically noticeable as unattractive by the general population.76 Therefore, the perceived need for treatment (i.e., de facto orthognathic surgery) for the Class III patient—whether by the public, the evaluating clinicians, the affected individual, or the patient’s family and friends—will be high.13,72,78,125 There is a strong family tendency for a Class III skeletal pattern. The so-called “Habsburg jaw” within the royal European family is well documented.58,104,106,122,124 The frequency of Class III skeletal patterns among white people of European or North American ancestry is reported to have a prevalence in the low single digits. There is a somewhat higher prevalence of Class III skeletal patterns among Africans than among Caucasians.27 Data from Japan, Korea, and China confirm a more frequent Class III pattern among Asians than among any other subgroup (i.e., >4%).28,117 Incidence rates of Class III malocclusion of as high as 13% have been reported in specific regions of Asia.119 Lew and colleagues examined occlusal parameters in 1050 Chinese schoolchildren who were between 12 and 14 years old.48 They found an incidence of 12.6% for Class III malocclusion, 58.8% for Class I occlusion, and 21.5% for Class II malocclusion. Samman and colleagues investigated 300 Chinese individuals residing in Hong Kong who were known to have dentofacial deformities and who had been referred to an “orthognathic surgery clinic.”91 After excluding those individuals with cleft lip and palate, 222 study patients remained. Forty-seven percent of these individuals (n = 104) were found to have a Class III skeletal malocclusion. Despite hereditary tendencies, the development of a Class III jaw disharmony is believed to be multifactorial and complex.8,33,39,57 Alternatively, it has been documented that environmental factors have a significant effect on vertical facial growth (see Chapter 21). The combination of an individual’s hereditary tendency toward a Class III skeletal pattern and a longstanding, forced mouth breathing, open-jaw posture during growth explains the occasional occurrence of a long face growth pattern (i.e., excess vertical growth) with Class III negative overjet malocclusion.29 An outlier for a Class III skeletal pattern is the impaired midface growth that is seen in many individuals from all backgrounds with repaired cleft palates (see Chapters 32, 33, and 34). Another commonly seen clinical pattern is the individual with maxillary vertical deficiency and a prominent pogonion (i.e., pseudoprognathism) as a result of “over closure” (see Chapter 23).97,99,109 An additional source of data regarding the prevalence of individuals with skeletal Class III is the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, a large-scale epidemiologic survey of the U.S. population that was carried out during the 1990s (see Chapter 3).77 The data from this study confirm that Class III problems increase from early childhood through adolescence.1,18 This can be explained by the expected late growth spurt in the mandible as compared with the maxilla. The study also confirmed that the presence of 2 mm or more of negative overjet is about twice as likely to occur among African Americans than among Caucasian Americans or Mexican Americans. Data from a U.S. public health survey of youths between the ages of 12 and 17 years indicates that about 14% have a mandibular first molar that is mesial in relation to the maxillary first molar.42 With regard to treatment, by the late 1800s, both Edward Angle, an orthodontist, and Vilray Blair, a surgeon, recognized that orthodontic treatment alone could not solve the Class III skeletal problem.15 Angle suggested that the only possible way to correct a true mandibular protrusion was with a combination of orthodontics and surgery.2 By the late 1800s, the initial orthognathic procedures were carried out to “set-back” the prominent mandible (see Chapter 2). • Predictable articulation errors in speech result from a Class III malocclusion (see Chapter 8). • Chronic obstructed nasal breathing is commonly seen in the presence of maxillary deficiency (see Chapter 10). • Characteristic difficulties with swallowing and chewing as a result of a Class III malocclusion are expected (see Chapter 8). • Wide lip separation (often with upper lip hypotonia) and mentalis strain required for lip seal are commonly seen in the presence of a significant negative overjet. • Detrimental long-term effects on the dentition and the periodontium that result from a Class III malocclusion (secondary occlusal trauma), dental crowding, or previous camouflage orthodontics are often seen (see Chapter 6). • The incidence of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) may be higher among these patients than among individuals with normal jaw harmony and occlusion (see Chapter 9). • Long chin–neck length and acute angle with a visually accentuated inferior border of the mandible • Prominent chin with a reduced labiomental fold • Protrusive and thick lower lip and vermillion • Sunken-appearing midface (A negative vector relationship between the ocular globe and the lower eyelid as a result of anterior maxillary deficiency is a frequent finding.) • Deflated, short, hypotonic appearance of the upper lip, with a thin vermillion • Sunken-appearing cheeks (i.e., the impression of flat cheek bones) • Middle one third of the face appears flat and long • Increased scleral show (i.e., pulling down of the lower lids) • Narrow alar base with paranasal flattening • Flat and relatively short upper lip with reduced vermillion exposure • Normal to deficient maxillary tooth to upper lip relationship frequently seen • Minimal attached gingiva over the labial aspects of the mandibular anterior teeth is frequently seen (see Chapter 6). • Mandibular incisors are usually upright or lingually inclined. • Interdental spacing with flared mandibular incisors may also be seen, especially in the presence of an anterior open bite with lip incompetence. • Class III malocclusion (molar and canine) with anterior open bite, negative overjet, and posterior crossbites is frequent. • Narrow maxillary arch width is seen as excess negative space in the buccal corridors. • Dental crowding with flared maxillary incisors is frequent. • Maxillary horizontal deficiency • Concave anterior maxilla consistent with a negative vector relationship of the ocular globe to the lower eyelid • Flat, counterclockwise-rotated maxillary plane • Procumbent maxillary incisors • Flat base of the nose with retrusive pyriform rims • Altered lower anterior facial height (either short or long) • B-point is anterior to or in front of A-point in profile (i.e., natural head position) • Negative overjet to the occlusion • Prognathic-appearing mandible • Lingually inclined mandibular incisors frequently found • Chin morphology varies, but it is generally dysmorphic. Frequent patterns of chin dysmorphology include vertical excess with either a prominent or flat pogonion. Most studies have found no difference in the ultimate size of the mandible between children with Class III conditions who were treated with a chin cup and those who were not.105 Wylhelm-Nold and colleagues presented some evidence that the use of the chin cup in preschool-aged children was able to decrease mandibular anterior growth if good compliance was achieved.123 Unfortunately, this did not prevent the mandible from continuing an excess growth pattern later during childhood, after the chin cup treatment was stopped. In fact, a rebound accelerated growth effect was documented. What chin cup therapy may accomplish is a change in the growth vector of the mandible, with more downward and backward (clockwise) rotation.37 These secondary changes have their own negative effects on facial morphology and occlusion (i.e., the law of unintended consequences). With the realization that the presenting maxillary deficiency should be the primary focus of the correction for most skeletal Class III individuals, growth modification moved toward methods of stimulating the upper jaw. The Delaire face mask has been used extensively to pull the maxilla forward.24 The work of Baccetti and McNamara confirmed that use of the Delaire face mask for the individual with maxillary deficiency is more likely to have effect when it is used before the patient is 8 years old.6,21,92 After this age, tooth movement (dental compensation) and mandibular clockwise rotation will be the likely consequences of this form of treatment rather than the hoped for horizontal maxillary projection. In addition, many children experience recurrence of the deformity after face mask therapy is discontinued. It is unlikely that face mask (for the maxilla) and chin cup (for the mandible) interventions will be effective in the long term for preventing the need for orthognathic surgery in all but mild cases. An accepted guideline is that more than 2 to 4 mm of reverse overjet in the preadolescent child indicates that surgery will eventually be needed if both facial and dental correction are sought. DeClerck and colleagues used orthopedic traction on the maxilla and compression on the mandible with temporary mini-plate skeletal anchorage and elastics in a limited number (n = 3) of 10- to 11-year-old children presenting with skeletal Class III malocclusions.25 Pure bone-borne orthopedic forces were applied with intermaxillary elastics on the skeletally anchored mini-plates. This approach was shown to either enhance midface growth or to hold back the mandible; in any case, the intent was to produce a corrected overjet. Although the authors were encouraged, many unknowns remained, including the ideal age for this type of orthopedic traction; the effect of the direction of force on the rotation of the palatal and mandibular planes; the long-term effects on the temporomandibular joints; and the need for retention to prevent catch-up growth of the mandible or relapse of the maxilla afterward. DeClerck’s ongoing prospective clinical trial of this promising work on a larger sample of patients (as well as the work of other independent researchers) will help to answer these questions and to determine the true effectiveness of a growth-modification approach that involves temporary skeletal anchorage and elastics.21,92 It is not uncommon for the orthognathic surgeon to see an adult in consultation who is emotionally exhausted after having undergone failed growth modification followed by disappointment after additional years of camouflage orthodontics. The individual may present with 1) significant residual malocclusion (i.e., effects on speech, swallowing, and chewing) 2) deteriorating periodontal health (i.e., crest bone loss and gingival recession associated with lower anterior and upper posterior teeth), 3) often with chronic upper airway obstruction (i.e. deviated septum, hypertrophic inferior turbinates, and tight nasal apertures) and 4) self-esteem and body image issues related to the facial disproportion and disappointment with failed treatment (Figs. 20-1 through Fig. 20-4). Figure 20-1 A 34-year-old male arrived for the evaluation of a longstanding jaw deformity with malocclusion, chronic obstructive nasal breathing, and periodontal issues. Since his early childhood years, the patient was known to have a maxillary deficiency with a relative mandibular excess growth pattern. The family elected a camouflage orthodontic approach that included four bicuspid extractions and the introduction of dental compensation in an attempt to neutralize the occlusion when the patient was 10 to 15 years old. He is a forced mouth breather as a result of increased nasal airway resistance. The patient underwent septoplasty when he was 20 years old, but significant improvement of the airway did not occur. His general dentist confirmed labial bone loss and gingival recession of the mandibular anterior and maxillary posterior dentition. He was referred to this surgeon, and a comprehensive orthognathic and dental rehabilitation approach was selected. Consultation with a periodontist, an orthodontist, and an ear, nose, and throat specialist was carried out. The patient was confirmed to have residual deviation of the septum and enlarged inferior turbinates, which explained the continual difficulty that he had breathing through his nose. A degree of root resorption of the anterior dentition was confirmed. The need for gingival grafting to attain improved root coverage and to generate a wider band of attachment was recommended for tooth nos. 3, 11, 14, 19, 20, 23 through 26, 29, and 30. This will be followed by the orthodontic removal of dental compensation and then orthognathic and intranasal procedures to improve long-term dental health, to enhance facial aesthetics, and to open the upper airway. A, Frontal facial and occlusal views before retreatment. B, Profile facial and lateral cephalometric radiograph before retreatment. C, Panorex radiograph before retreatment. Figure 20-2 A 26-year-old man arrived for surgical evaluation. Since the mixed dentition, he had been recognized as having a developmental jaw deformity characterized by maxillary deficiency in combination with relative mandibular excess. Camouflage orthodontic treatment that included four bicuspid extractions was carried out when the patient was between 12 and 16 years old. A residual Class III negative overjet with an anterior open-bite malocclusion remains. The patient has never been able to breathe well through the nose as a result of septal deviation and inferior turbinate enlargement. Secondary occlusal trauma resulted in the need for root canal therapy and crowns in all four posterior quadrants. There is labial bone loss and gingival recession associated with the anterior mandibular teeth. A comprehensive dental rehabilitative and reconstructive approach will require periodontal evaluation and treatment followed by orthodontic decompensation and then by jaw and intranasal surgery. A, Frontal facial and occlusal views before retreatment. B, Profile facial view and lateral cephalometric radiograph before retreatment. C, Panorex radiograph before retreatment. Figure 20-3 A 30-year-old man arrived for the evaluation of a longstanding jaw deformity with malocclusion, chronic obstructive nasal breathing, and an awareness of periodontal issues. Since his early childhood years, he was known to have a jaw deformity with malocclusion, including an anterior open bite. When he was between 8 and 12 years old, he underwent orthodontic camouflage treatment in an attempt to close the open bite; this included full bracketing and the use of heavy anterior elastics. By the time that he graduated from high school, he was conscious of a significant recurrent anterior open bite with dental crowding. Throughout his college years, he was aware of gingival recession on the labial aspect of many of the anterior teeth of the maxilla more so than the mandible. He was sent by his general dentist for an orthodontic evaluation and then to this surgeon for an opinion. The patient was referred for periodontal evaluation with confirmation of significant labial bone loss of the anterior dentition (more so on the maxilla than the mandible) and gingival recession. A comprehensive approach was recommended; this would include gingival grafting and four bicuspid extractions, with orthodontic retraction of the anterior dentition into the solid alveolar bone. This would be followed by jaw reconstruction, finishing orthodontics, and periodontal surveillance. A, Frontal facial and occlusal views before retreatment. B, Profile facial view and lateral cephalometric radiograph before retreatment. C, Panorex radiograph before retreatment. Figure 20-4 A 29-year-old man arrived for the evaluation of a longstanding developmental jaw deformity characterized by maxillary deficiency with relative mandibular excess. There is malocclusion and chronic obstructive nasal breathing. By the time he was 13 years old, he was referred by his pediatric dentist to an orthodontist for the evaluation of a Class III negative overjet malocclusion. He then underwent a 2-year course of compensatory orthodontics in an attempt to neutralize the occlusion. He was left with an Angle Class III negative overjet and early signs of gingival recession. The patient also has a history of stress-induced asthma and chronic obstructed nasal breathing. He uses Flonase, Singulair, and other medications in an effort to open the nasal airway, and he is also being seen by an allergist. For his gingival recession, he was referred to a periodontist, and connective tissue grafting was carried out for the lower anterior dentition on several of the maxillary posterior teeth. An orthodontic consultation confirmed crowding, the proclination of the maxillary anterior dentition, and uprighted mandibular anterior teeth. Evaluation of the upper airway documented a deviated septum and hypertrophic inferior turbinates. An orthodontic and surgical approach was recommended to limit further secondary dental trauma, to stabilize the periodontium, and to correct the occlusion. A, Frontal facial and occlusal views before retreatment. B, Profile facial and lateral cephalometric radiographs before retreatment. C, Panorex radiograph before re-treatment. • Moderate or severe Class III patterns (i.e., >4 mm of reverse overjet) • Moderate to severe vertical skeletal discrepancies • Significant dental crowding in the lower jaw and significant anterior dental protrusion in the upper jaw • A concern that the planned orthodontic mechanics may cause periodontal deterioration • A desire for enhanced facial aesthetics Skeletally immature individuals with true mandibular excess can be expected to outgrow any early orthodontic or surgical corrections and later require further treatment.7,17,83,90 Indirect methods of assessing growth maturity (e.g., a hand–wrist film to determine bone age) are not accurate enough to be used in isolation for planning the timing of surgery. A reasonable method to assess growth maturation is through the analysis of serial lateral cephalometric radiographs. These radiographs can be used in two ways: for a cervical vertebral analysis or to make sequential direct mandibular measurements. Surgery is delayed until the deceleration of growth can be documented. The use of a quantitative condylar head bone scan can also be helpful to evaluate the growth of the mandible in the adolescent, but both false-positives and false-negatives may occur. If the Class III condition is largely the result of maxillary deficiency, gauging the preferred timing of surgery is more straightforward, because the late postsurgical growth of the mandible is less likely (see Chapter 17). Alexander and colleagues completed a study of craniofacial growth changes in Caucasians with untreated Class III malocclusions by using longitudinal cephalometric records (n = 103).1 In girls, the mandibular growth spurt generally occurred between the ages of 10 and 12 years. In boys, the growth spurt was usually between the ages of 12 and 15 years. In some of the Class III subjects, limited degrees of mandibular growth relative to that of maxillary growth were documented to continue after the adolescent spurt. After the age of 13 years in girls and 15 years in boys and until closer to the age of 17 years, annual increments of mandibular growth were often between 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm, whereas increments of midface length dropped to less than 1 mm. The authors concluded that the differential growth behavior of the two jaws among individuals with Class III conditions may result in recurrent jaw disharmony and malocclusion when orthodontic or surgical treatment is undertaken before or during puberty. • Assess for active gingivitis or periodontitis and the need for treatment. • Assess the current level of oral hygiene and the need for a home care program. • Assess for the effects of occlusal trauma and malocclusion on the periodontium. • Assess the level of attached gingiva and the need for augmentation. • Confirm the adequacy of the alveolar bone and the need to create space with the use of extractions. • Assess the need for restorations to remove decay, to replace deficient enamel, and to achieve a healthy gingival interface. 1. Before orthodontic decompensation, assess the level of attached gingiva, the position of the labial and lingual plates, and the alveolar crest heights. Consider the effects of any planned orthodontic maneuvers on the periodontium. 2. Make decisions about the tooth (root) size to alveolar volume discrepancies in each arch and the need for extractions to establish and preserve periodontal health. 3. Create a plan (i.e., separate surgical and orthodontic objectives) to achieve preferred anteroposterior and vertical incisor positions in the maxilla and the mandible. 4. Understand how the orthodontic objectives become more limited when they are combined with the planned surgical procedures (e.g., maxillary segmentation, bimaxillary osteotomies) to then achieve the final desired arch form, midline positioning, occlusion, and facial symmetry and proportions. 5. Make decisions about orthodontic mechanics and anchorage requirements to achieve the chosen objectives. 6. At the end of the presurgical orthodontic phase (i.e., 4 to 6 weeks before surgery), full-dimensional stabilizing (i.e., passive) arch wires should be in place. The placement of surgical hooks can be done just before surgery. When an accentuated curve of Spee is present in the lower arch of a patient with Class III malocclusion, it is managed through a combination of intrusion of the incisors and extrusion of the premolars or molars.20,49 In preparation for surgery, repositioning the lower incisors forward is generally advantageous for the Class III skeletal pattern. Therefore, lower arch extractions are rarely indicated. If limited labial bone is present, a periodontal evaluation is recommended before the incisors are orthodontically moved forward. If gingival recession has occurred or if the gingiva is genetically inadequate, augmentation grafting procedures are indicated (see Chapter 6). If the upper arch is narrow, then orthodontic leveling is performed in segments in anticipation of surgical management.8,14,16,22,71,88,95,114 If the curve of Spee is excessive as a result of vertical skeletal dysplasia, then leveling is also done in segments in preparation for surgical correction (see Chapter 17). In the presence of maxillary deficiency, limited space to uncrowd the upper teeth may leave the roots tipped outside of the solid alveolar housing. In this circumstance, maxillary first bicuspid extractions with space closure before surgery is preferred. With only borderline crowding, extractions are often not carried out. Limited dental space deficiency can often be managed through the judicious use of interproximal reduction. In addition, the aesthetic consequences of mildly proclined incisors (i.e., A-point to B-point discrepancy in profile) can be improved via the clockwise rotation of the maxillomandibular complex at the time of surgery (see Chapters 12 and 13). The immediate presurgical planning takes into account collaborative clinical efforts between the orthodontist, the surgeon, the patient, and the patient’s family that will have been ongoing since the initial consultation visits.32,74,75,84,93,98

Maxillary Deficiency with Relative Mandibular Excess Growth Patterns

Functional Aspects

Clinical Characteristics

Profile View

Frontal View

Dental Characteristics

Radiographic Findings

The Role of Growth Modification in the Preadolescent Patient

Orthodontic Camouflage Approach

Definitive Reconstruction

Timing of Orthognathic Surgery

Pre-Orthodontic Periodontal Checklist (see Chapter 6)

Orthodontic Preparation for Orthognathic Surgery

Leveling the Mandibular Arch

Leveling of the Maxillary Arch

Immediate Presurgical Planning

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Maxillary Deficiency with Relative Mandibular Excess Growth Patterns