Identifying those patients with the highest risk leads to the greatest success in reducing postoperative nausea and vomiting by modifying the anesthetic plan to decrease baseline risk, and implementing the appropriate use of prophylaxis. The strategies that will be effective in the reduction of postdischarge nausea and vomiting are currently being studied.

Key points

- •

The Consensus Guidelines for Managing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) provides an evidence-based management strategy for clinicians.

- •

Although the exact cause of PONV is unknown, many receptors, pathways, and neurotransmitters are likely involved. Because of the multitude of inputs that may be causal, single therapies are often inadequate.

- •

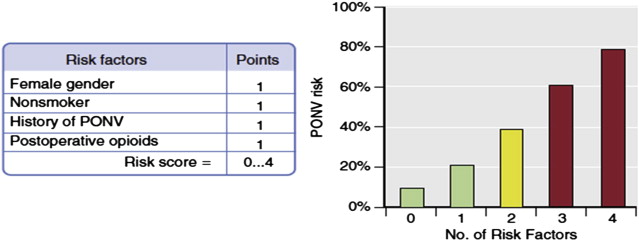

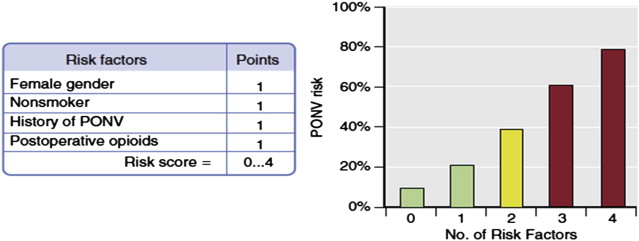

An individual’s risk for PONV is best predicted by using a simplified risk score of independent predictors: female gender, nonsmoking status, history of PONV or motion sickness, and postoperative opioid use.

- •

Although some types of surgery, plastic surgery among them, are associated with higher PONV risk, risk scores that include type of surgery provide no greater predictive value.

- •

Strategies that avoid inhaled anesthetics such as total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA), elimination of nitrous oxide, and minimal opioid use reduce risk.

- •

Multimodal regimens involving TIVA with propofol, combination antiemetic prophylaxis, hydration, and nonnarcotic analgesics, are the most effective way to prevent PONV in high-risk patients.

- •

Postdischarge nausea and vomiting is common in ambulatory surgery patients. Those who have nausea in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) are particularly at risk. Which agents in addition to dexamethasone are effective remains to be determined.

Considerable progress has been made in the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) since it was labeled the big little problem over 20 years ago by Kapur. Although usually self-limited, it is distressing to patients who, in some studies, state they would pay up to $100.00 out of pocket for a drug to avoid it. PONV can lead to dehydration, electrolyte disturbances, and the inability to take vital oral medications and fluids after surgery. The act of vomiting can cause suture disruption, lead to hematoma formation, and be a risk factor for pulmonary aspiration. Its occurrence often delays discharge from ambulatory settings and is a leading cause of unanticipated hospital admission escalating health care costs. With most surgeries now being done on an outpatient or ambulatory basis, considerable attention is being given to this issue.

The Consensus Guidelines for Managing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting authored by an international panel of experts created an evidence-based management strategy for clinicians. These guidelines have been the foundation for the improved understanding and recent advances gained regarding this common, undesirable perioperative experience. However, there is still room for improvement, particularly in the area of postdischarge nausea and vomiting (PDNV), which occurred in up to 37% of ambulatory patients in a recently published study.

Pathophysiology of nausea and vomiting

Various stimuli that produce nausea and vomiting converge in an area of the medulla known as the emetic center. This center is not a discrete nucleus but rather a collection of neurons controlled by a central pattern generator. Input to the emetic center comes from a variety of pathways: the visceral afferent nerves of the gastrointestinal tract, the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), the cerebral cortex, and the vestibular apparatus. Each of these systems is modulated by specific receptors and neurotransmitters. The CTZ is located in the fourth ventricle of the brainstem but, because of its uniquely permeable membrane, it is outside the blood-brain barrier, which allows detection of toxins and drugs in the circulation. Stimulation of dopamine, opioid, histamine, acetylcholine, serotonin type 3 receptors, or neurokinin-1 receptors in the emetic center initiates the vomiting reflex. Therapies that interfere with each of these neurotransmitter-receptor interactions are used to prevent nausea and vomiting in clinical practice. Because of the multitude of inputs that may be causal in the production of nausea and vomiting, single therapies are often inadequate.

Assessing risk for PONV

The important first step in managing PONV is to assess risk for each patient. In doing so, there are 3 categories of factors to consider:

Patient-specific factors:

- 1.

Female gender

- 2.

Nonsmoking status

- 3.

History of PONV or motion sickness

Anesthesia-related factors:

- 1.

Use of volatile anesthetics

- 2.

Use of nitrous oxide

- 3.

Perioperative opioid use

Surgery-related factors:

- 1.

Duration and invasiveness of surgery

- 2.

Type of surgery

A simplified risk score of independent predictors by Apfel and colleagues has gained widespread recognition and implementation by anesthesia providers. Although some types of surgery (plastic, strabismus, gynecologic, laparoscopic, urologic) are known to be associated with a higher PONV risk, risk scores that include type of surgery provide no greater predictive value than a simplified version. For example, hysterectomy is known to have a higher PONV risk. It may be that this increased risk is a reflection of the patient population who are female (the strongest risk factor) rather than the surgery itself. Patients having plastic surgery are predominantly women, making them inherently at higher risk. The simplified risk score for an adult having a balanced inhalational anesthetic consists of the following 4 factors: female gender, nonsmoking status, previous history of PONV or motion sickness, and postoperative opioid use. The presence of 1 risk factor correlates with a risk of 20% for PONV. Each additional risk factor adds 20%, so that patients with all 4 have an 80% risk of developing PONV ( Fig. 1 ).

Assessing risk for PONV

The important first step in managing PONV is to assess risk for each patient. In doing so, there are 3 categories of factors to consider:

Patient-specific factors:

- 1.

Female gender

- 2.

Nonsmoking status

- 3.

History of PONV or motion sickness

Anesthesia-related factors:

- 1.

Use of volatile anesthetics

- 2.

Use of nitrous oxide

- 3.

Perioperative opioid use

Surgery-related factors:

- 1.

Duration and invasiveness of surgery

- 2.

Type of surgery

A simplified risk score of independent predictors by Apfel and colleagues has gained widespread recognition and implementation by anesthesia providers. Although some types of surgery (plastic, strabismus, gynecologic, laparoscopic, urologic) are known to be associated with a higher PONV risk, risk scores that include type of surgery provide no greater predictive value than a simplified version. For example, hysterectomy is known to have a higher PONV risk. It may be that this increased risk is a reflection of the patient population who are female (the strongest risk factor) rather than the surgery itself. Patients having plastic surgery are predominantly women, making them inherently at higher risk. The simplified risk score for an adult having a balanced inhalational anesthetic consists of the following 4 factors: female gender, nonsmoking status, previous history of PONV or motion sickness, and postoperative opioid use. The presence of 1 risk factor correlates with a risk of 20% for PONV. Each additional risk factor adds 20%, so that patients with all 4 have an 80% risk of developing PONV ( Fig. 1 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree