Chapter 56 Management of contractural deformities involving the shoulder (axilla), elbow, hip and knee joints in burned patients

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Contractural deformities of the shoulder (axilla), elbow, hip and knee observed in a burned patient

The factors leading to formation of the contractural deformities

Folding bodily joints in flexion, a so-called posture of ‘comfort’, is a characteristic body posture seen commonly in a distressed individual. Although the exact reasons are not entirely clear, contraction of muscle fibers at rest and contractile force difference between the flexor muscle and the extensor muscle play an important role in the genesis of this body posture. The magnitude of joint flexion, furthermore, increases as an individual loses voluntary control of muscle movement, as frequently occurs in a burn victim (Fig. 56.1). A prolonged period of physical inactivity associated with burn treatment and scar tissue contraction around the joint structures as the recovery ensues, further impedes the joint mobility.

Incidence of burn contracture involving the shoulder (axilla), elbow and knee joints

Burn treatment that requires a long period of bed confinement and physical inactivity as well as restriction of joint movement will lead to joint dysfunction. Consequently, every bodily joint, i.e. the vertebral, mandibular, shoulder, elbow, finger, hip, knee and toe joints, are susceptible to changes. Of various bodily joints involved, the contractural deformities of the shoulder (axilla), elbow, hip and the knee are relatively common. Factors such as a wide range of joint movement and an asynchronous muscular control characteristic features of these joints, when combined with a high vulnerability to burn injuries, are the probable reasons accounting for the high incidence encountered. Recent review of the records of 1005 patients treated at the Shriners Burns Hospital in Galveston, Texas, over the past 25 years, indicated that the elbow was the joint most commonly affected. There were 397 patients with elbow joint deformity followed by 283 knee contractures. There were 248 axillary deformities. The hip joint contracture was the deformity least encountered and was noted in only 77 patients (Table 56.1).

Table 56.1 The distribution of joint deformities

| Joint involved | n |

|---|---|

| Shoulder (axilla) | 248 |

| Elbow | 397 |

| Hip | 77 |

| Knee | 283 |

| Total | 1005 |

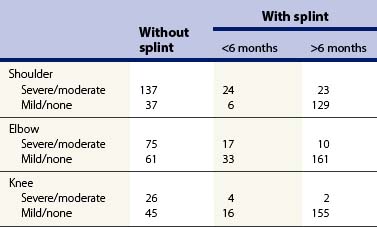

The efficacy of splinting in controlling burn contractures of shoulder (axilla), elbow and knee joints

Although Cronin in 1955 demonstrated that the neck splint was effective in preventing recurrence of neck contracture following surgical release,1 the routine use of splinting for burn patients did not become a part of the regimen of burn wound care in Galveston until 1968 when Larson, the former Surgeon-in-Chief and Willis, the former Chief Occupational Therapist at the Shriners Burns Institute, began to fabricate splints with thermoplastic materials to brace the neck and extremities.2–5

A study was conducted in 1977 to determine the efficacy of splinting across large joint structures such as the elbow, axilla and knee joints by reviewing the records of 625 patients. There were 961 burns over these joints in this group of patients. Of these, 356 had involved the axillae, while 357 and 248, respectively, involved the elbow and the knee joint. The incidence of contractural deformities encountered in these joints was, as expected, low with the use of splints. The incidence of contractures in these joints was 7.3%, provided that patients had worn the splints for 6 months. The effectiveness of splinting was diminished to 55% if splinting was discontinued within 6 months. For comparison, the incidence of contractural deformity ascertained in 219 patients who had never worn the splint was 62% (Table 56.2).

Although splinting and bracing were shown to be effective in minimizing joint contracture, it was not entirely clear if restriction of joint movement would affect the quality of scar tissues formed across the joint surface. The effects were assessed by determining the frequency of secondary surgery performed in this group of patients. Over 90% of 219 individuals who did not use the splint/bracing, required reconstructive surgery. In contrast, the need for surgical reconstruction in individuals who wore splints was 25%.6

Management during the acute phase of recovery

Body positioning and joint splinting

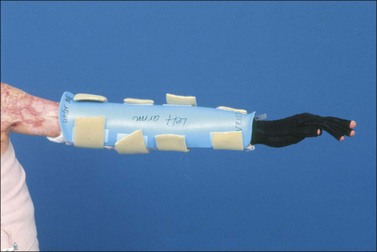

Elbow joint

Elbow flexion is commonly seen in a distressed patient. Rigid flexion contracture of the elbow is a common sequela if the elbow is left unattended. With burns of the skin around the olecranon, exposure of the elbow joint is a common sequela if the elbow is allowed to contract freely. Maintaining the elbow in full extension therefore is essential. An extension brace (Fig. 56.2), or a three-point extension splint across the elbow joint is effective for this purpose (Fig. 56.3).

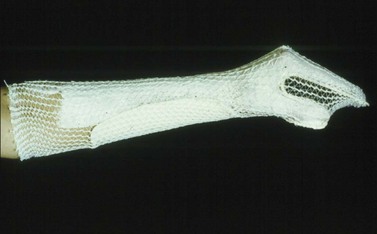

Wrist joint

A contractural deformity involving a wrist joint is relatively common in individuals with hand burns that were not splinted properly. A cock-up hand splint should be applied to maintain a 30° wrist extension (Fig. 56.4).

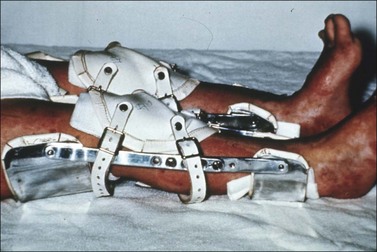

Knee joint

Flexion of the knee is another posture commonly assumed by a burned victim. Similar to the elbow, uncontrolled flexion of the knee joint will lead to exposure of the joint structure, especially in instances where the injuries involved the patella surface. Maintenance of knee in full extension is, in this sense, an essential component of therapeutic regimen. This is accomplished by means of a knee brace or a three-point extension splint to assure a full extension of the knee joint (Fig. 56.5).

Management during the intermediate phase of recovery

A period starting from the 2nd month following the injury through the 4th month is considered as the intermediate phase of recovery from burn injuries. The burn victims typically will have full recovery of physiologic functions with integumental integrity restored. The cicatricial processes around the injured sites, on the other hand, are physiologically active though healing of the burned wound is considered satisfactory. That is, the process is characterized by, in addition to a maximal rate of collagen synthesis, a steady increase in the myofibroblast fraction of the fibroblast population in the wound;7 the cellular change believed to account for contraction of the scar tissues. Continuous use of splinting and pressure to support the joints and burned sites, in this sense, is essential in order to control changes caused by ensuing scar tissue formation and scar contracture.

Bodily positioning and joint splinting

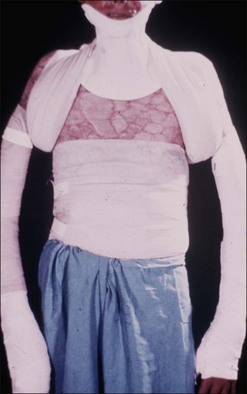

Joint splinting and bodily positioning are similar to the regimen used during the acute phase of burn recovery. That is, the shoulder is kept at 15–20 degree flexion and 80–120 degree abduction. A ‘figure-of-eight’ wrapping over an axillary pad is used to maintain this shoulder joint position (Fig. 56.6). The elbow and knee joints are maintained in full extension by means of a three-point extension splint or brace. A pressure dressing or garment is incorporated in the splint. In instances where the use of ‘figure-of-eight’ bandage, pressure dressing and/or garment, is not feasible because of recent surgery, devices such as an ‘airplane splint’ device (Fig. 56.7), or a three-point extension splint may be used to splint the axilla, elbow and the knee joints.