and Peter M. Prendergast2

(1)

Elysium Aesthetics, Bogota, Colombia

(2)

Venus Medical, Dublin, Ireland

Introduction

In the past, liposuction was a procedure dedicated only to removing unwanted fat. There was no surgical option for slimming or creating an athletic form. In men, the “six-pack” abdomen defines an athletic and masculine appearance. In reality, few men have the combination of genes, dietary habits, and exercise required to develop and reveal the bellies of the rectus abdominis that produce the “six-pack.”

The most common request from men who seek body contouring is a well-defined “six-pack” abdomen. Women desire a flat abdomen and occasionally seek limited definition of the anterior abdominal wall. Even athletes with intensive physical training regimens become frustrated with their inability to lose unwanted fat in certain areas. In these individuals, a genetic predisposition to storing fat in areas that obscures muscular definition makes it almost impossible to develop a highly defined muscular appearance.

The approach to high-definition body sculpting depends on the patient’s body type and body mass index [1–5]. If the patient is overweight, the main focus of the surgery will be to remove as much fat as possible first and then reveal the anatomy. If he is already slim or athletic, the fat removal will serve to reshape and not to “debulk.” For those slim patients, we use intramuscular autologous fat grafting to augment poorly defined muscles [3, 6]. Regardless of preoperative body type, the singular goal of high-definition body sculpting in the male patient is to produce an athletic, muscular appearance (Fig. 8.1) [3]. Once patients see the results of the procedure, they are more inclined to lead a healthy lifestyle to maintain their new appearance. As results improve with diet and exercise, a cycle of positive feedback is created that motivates the patient further and continues to improve results over time.

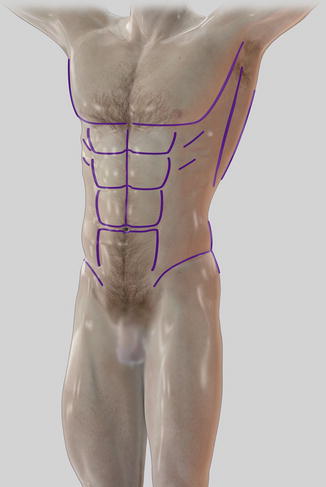

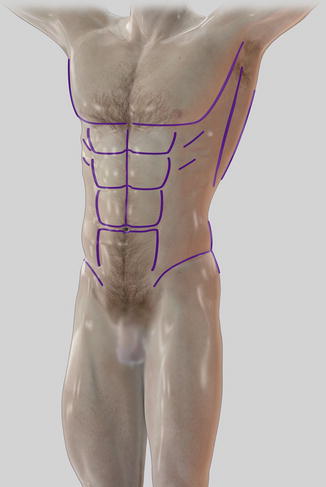

Fig. 8.1

Athletic abdominal muscles in male

Stealth Incisions

Numerous incisions are required in order to perform high-definition lipoplasty. Consideration must be given to the location of these incisions. As surgeons, the balance lies between operating comfortably from easy access sites that leave visible scars and hiding incisions in concealed folds or creases, at the cost of working from awkward positions that may necessitate additional incisions to reach all contours anyway.

Even small incisions can leave conspicuous scars, particularly if they are hyperpigmented or hypertrophic. Various factors influence the healing process, including age, race, presence of body hair in men, and the suturing method. When closure is indicated, the author prefers subdermal continuous sutures. The ideal access points should not leave visible scars over the abdomen or the back and should be hidden in the underwear or in the natural folds of the skin. This avoids stigmata of lipoplasty surgery, such as visible or symmetric linear scars. Even with good contouring results, some patients are reluctant to wear a bikini or sunbathe if noticeable scars are present.

The author has perfected the use of hidden or “stealth” incisions and developed various long and curved cannulae to comfortably access the entire body.

In men, the ideal incision points should be:

Pubis: below the hairline, two incisions in line vertically with the semilunaris lines (lateral rectus abdominis). These provide access to most of the abdominal area, including the flanks and waistline, and the rectus abdominis bellies.

Umbilical: provides access to the inferior abdominal area, vertical midline above the umbilicus, and central supraumbilical abdomen.

Nipple: in men this incision is the most hidden one, providing access to the pectoral area, the superior abdomen, and the superior flank and axillary areas.

Anterior axillary fold: provides access to the arm, pectoral area, and lateral chest. This site is essential for fat grafting in pectoralis major and minor and gynecomastia removal.

In the abdominal area, stealth incisions are always preferable. However, if additional access sites are necessary to define the horizontal tendinous intersections of the rectus abdominis, asymmetric incisions can be placed along the abdomen. The stealth incision sites are shown in Fig. 8.2.

Fig. 8.2

Abdominal incisions (arrows) with ports stitched in place

The Use of Drains

After treating the male abdomen and torso, drains should be placed in the inguinal area. The use of drains is necessary since aggressive liposuction of the flank area increases the risk of fluid collection in this area with gravity. Two drains are placed at the end of the procedure through the pubic incisions (Fig. 8.3). Either open or closed drains are acceptable, depending on the preference of the surgeon and patient.

Fig. 8.3

Postoperative drains in the pubical area in men

Markings

The preoperative markings are done in three steps with the patient in the standing position. It is recommended to use different color markers for different stages.

Deep Markings

First, the typical liposuction markings are made in the areas where extra fat is located: usually on the abdominal area, mostly infraumbilical, the “love-handles,” the flanks, the pectoral area, and lateral to it toward the axilla (Fig. 8.4).

Fig. 8.4

Common areas for deep fat extraction in men (blue)

Framing

The framing is the marking that represents the actual position of the muscles and other superficial anatomical landmarks (Fig. 8.5). The location of these landmarks might be defined by palpation with the patient at rest only but may require the patient to contract the muscles in specific areas. Sonographic guidance is particularly useful in most cases.

Fig. 8.5

Illustration showing the areas for superficial framing

The initial assessment of the position of the muscles and tone has to be done with the patient in the standing position:

1.

Ask the patient to inhale deeply until the costal margin is visible. Mark the costal margin bilaterally to define the cartilaginous thoracic arch.

2.

Palpate and mark the linea alba in the midline from the supraumbilical area to just below the xiphoid process. Remember that no midline should be marked below the umbilicus.

3.

Feel for the lateral borders of the rectus abdominis. If possible, try also to locate the transverse tendinous intersections by carefully palpating with the tips of the fingers. Ask the patient in the standing position to contract the abdominal muscles to find the grooves between the muscle bellies (Fig. 8.6). This is usually possible in thin and athletic patients, but may be more challenging in patients who are overweight or obese. Later we will discuss how to find them in obese patients.

Fig. 8.6

Markings on the patient. Arrows showing the transverse inscriptions of the rectus abdominis muscle

4.

Locate and mark the borders of the transverse and oblique muscles bilaterally. Ask the patient to push out the abdomen as much as possible. This maneuver reveals the shape of the muscles, particularly in patients with more intra-abdominal fat.

5.

Sit down in an oblique position from the patient and ask him to place his hand on your shoulder and then push your shoulder downward. The large latissimus dorsi in the posterior wall of the axilla can easily be marked as it contracts. With the arm in this position, the anterior bundles of the serratus anterior should also be visible on the chest wall below the pectoralis major. These are also marked (Fig. 8.7).

Fig. 8.7

Pushing down the arm against the surgeon’s shoulder. By this maneuver, the latissimus dorsi muscle and serratus muscles are contracted and easily seen for marking

Markings in the Obese Patient

In the obese patient, marking the anterior abdomen for high-definition body sculpting can be challenging. There are two main scenarios in obese patients: