Lip

BIOANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

The lips and perioral region are central features of appearance. The lips also provide oral competence at rest and during mastication. They are central to facial expression and are sensory organs both for food and personal contact. The lips have rich vasculature and sensory innervation.

The perioral region is bounded by the nasolabial folds laterally and superiorly and by the mental crease of the chin inferiorly. The lips are suspended only by muscles and the fibrous tissues of the modiolus at each oral commissure. For that reason, the lips and the oral commissures are mobile free margins, and reconstruction of the perioral region requires meticulous planning to direct tension in appropriate vectors. Pull on the upper lip margin creates the appearance of a “hair lip,” distortion of the lateral oral commissure can lead either to drooling or a sneer, and depression and/or eversion of the lower lip can lead to a loss of oral competence.

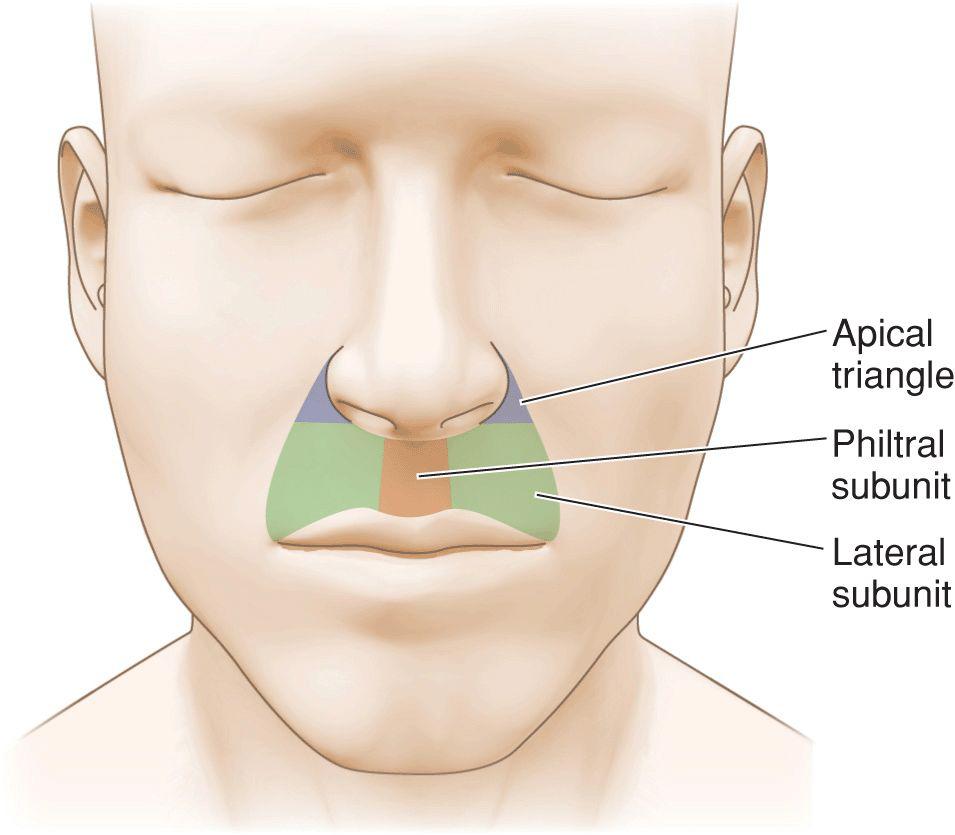

The upper lip is often divided into subunits (Fig. 9.1).1 The philtral subunit lies centrally and its lateral borders are the medial borders of the lateral subunits. The lateral subunits of the upper lip are bounded by the vermillion, the philtrum, the inferior margin of the ala, and the nasolabial fold. A small triangular extension of the lip that lies lateral to the ala and medial to the superiormost nasolabial fold is known as the apical triangle. Although small in size, it provides a recognizable declination between the lip, nose, and cheek, and it should be maintained as an aesthetic marker where feasible.

Figure 9.1 Lip subunits: The upper lip is divided into a philtral subunit and two lateral subunits. The lateral subunits each contain an apical or “sacred” triangle lateral to nasal ala. Maintaining the integrity of the philtrum, apical triangle, and nasolabial folds are goals of upper lip reconstruction

The inner margin of the lip is the mucosa of the mouth. The wet mucosa becomes vermillion as it exits the oral aperture and forms the red lip. Beneath the mucosa is a submucosal layer rich in minor salivary glands. The vermillion itself lies directly on a circumoral band of orbicularis oris and the underlying musculature has a rich vascular supply. This, coupled with a lack of keratinization, leads to the red color of the lip. The bulk of the lip is created by the orbicularis oris that forms concentric rings and gives the lips their shape, definition, and function.

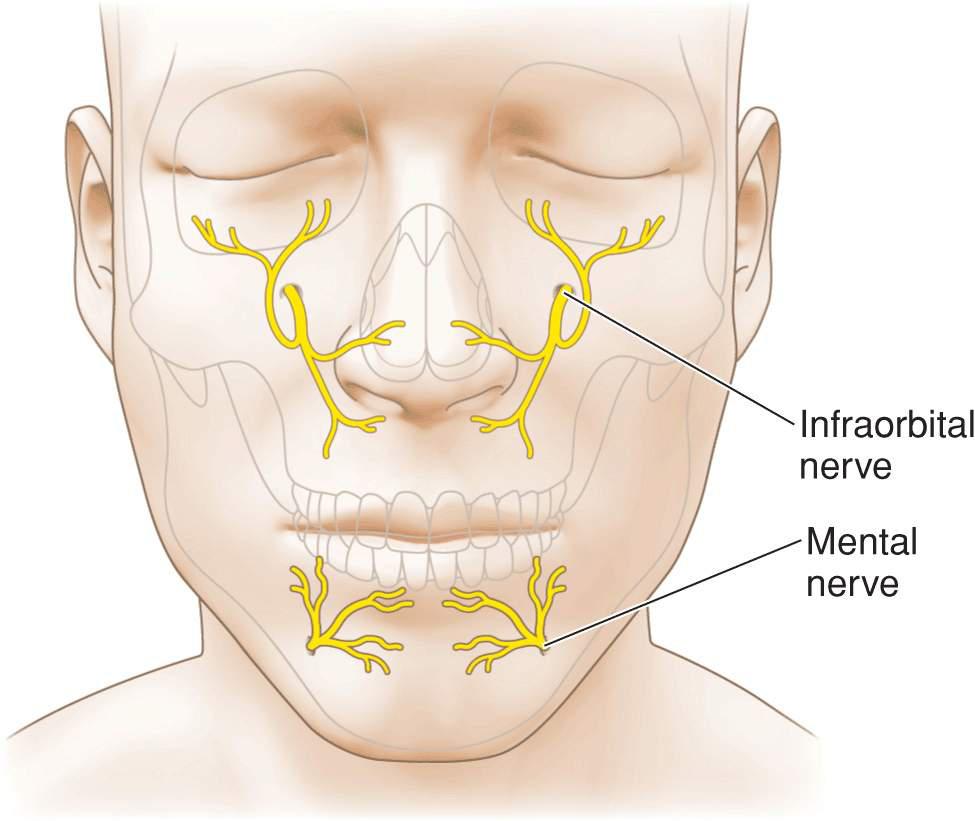

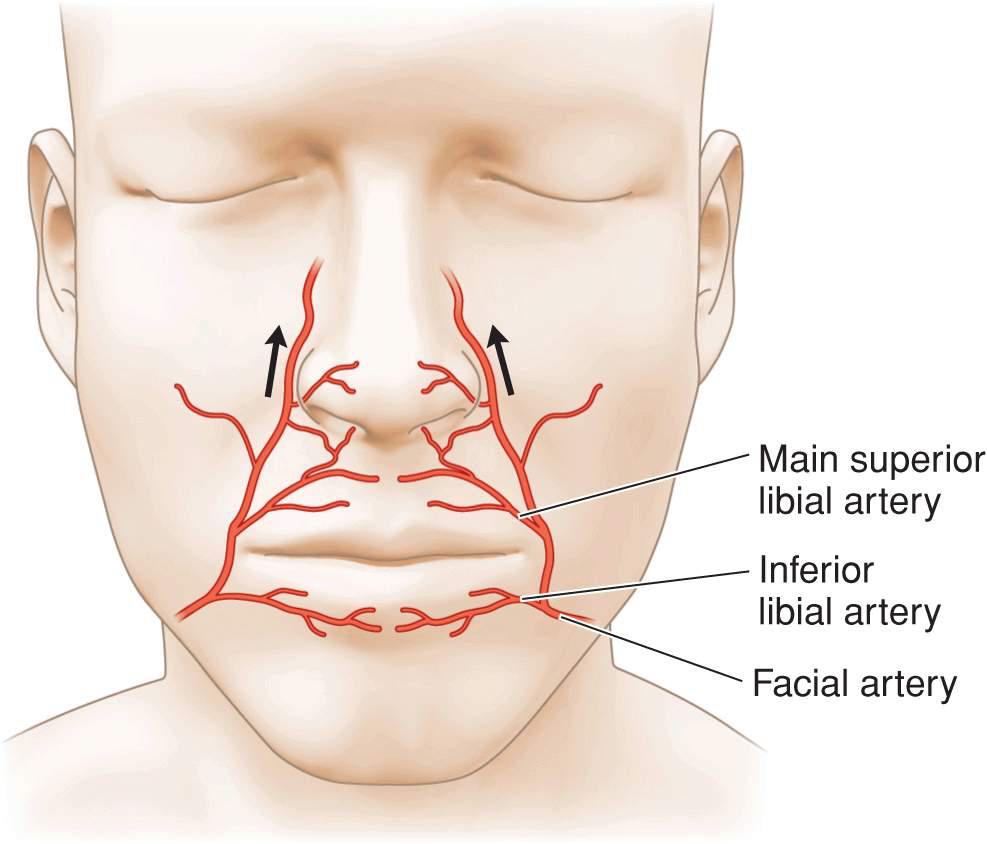

Motor innervation of the upper lip is from a plexus of nerves supplied by the zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches of the facial nerve. These nerves are highly anastomosed and deeply seated. Hence neural injury affecting perioral function is rare with the one exception being damage to the marginal mandibular nerve as it passes along the mandible. Sensory function of the upper lip is provided by the infraorbital nerve and the lower lip is innervated by the mental nerve (Fig. 9.2). Anesthesia of the lip is readily achieved by nerve block. The upper and lower lips each receive a large branch from the facial artery as it ascends toward the alar crease (Fig. 9.3). The arteries run in the submucosa and become tortuous with age. They give off many perforators and branches, anastomosing at the midline.

Figure 9.2 Sensory innervation of the perioral region. The upper lip is innervated by the infraorbital nerve and the lower lip is innervated by the mental nerve. The lateral commissures receive sensory input from the cervical nerves and require separate local anesthetic

Figure 9.3 Vasculature of the perioral region. The upper and lower lips are richly supplied by large labial branches of the facial artery. The labial branches are tortuous with age and run on the submucosal side of the orbicularis oris

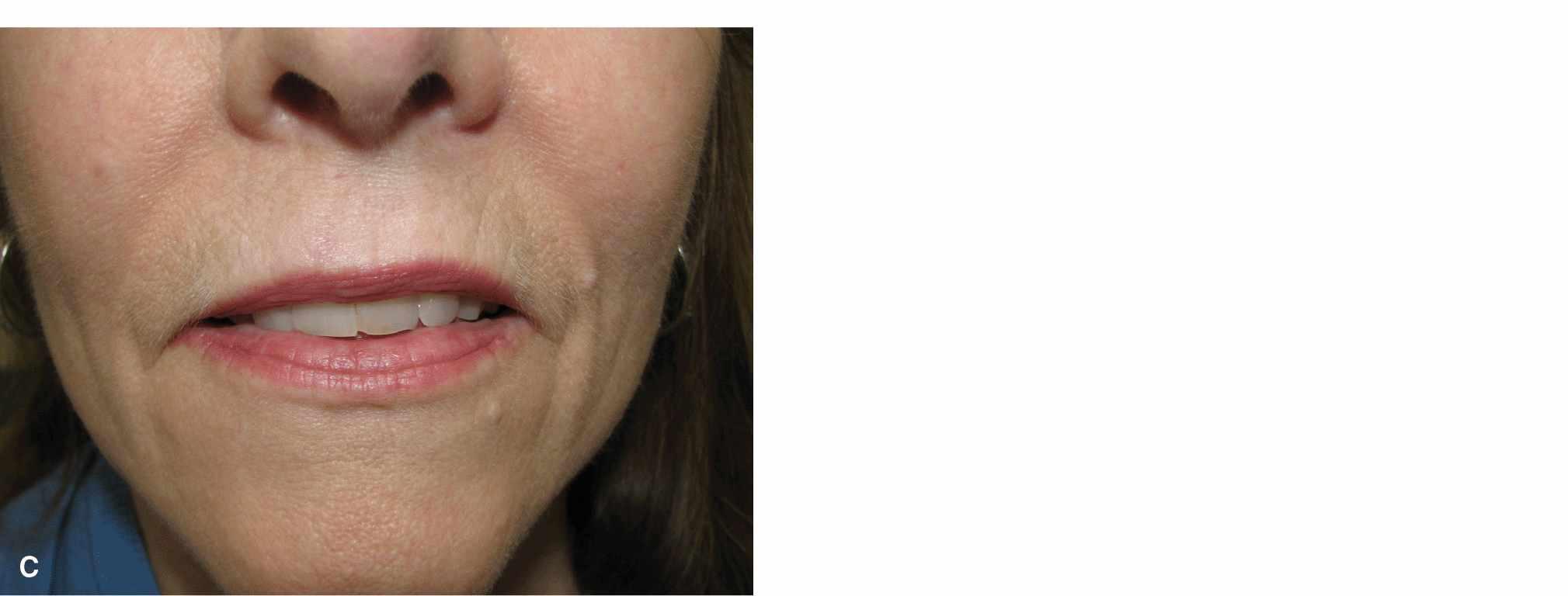

The junction of the vermillion and the cutaneous lip is a bright, clear line in younger adults. A thin, elevated, well-defined border of pale skin marks the border with the cutaneous lip. With age, this definition fades. The youthful lip often has a prominent philtrum and the vermillion border of the upper lip is crisp and voluminous. The nasolabial folds are not well developed in youth. Instead they are soft, minimally depressed inclinations. With age, the upper lip flattens, the philtrum is less prominent, and the vermillion border is less defined. The nasolabial folds become fixed and sharply recessed, clearly defining the lateral margin of the upper lip (Fig. 9.4).

Figure 9.4 Variation in the lip with age. (A) Lips of a 25-year-old woman. The vermillion is full and sharply defined. The philtrum is elevated and distinct. Repairs may be noticeable, even if the scar line is fine and sharp. (B) Lips of a 45-year-old woman. The vermillion has lost some volume. The philtrum has lost some elevation and is less distinct. A few vertical lines have formed. (C) Lips of a 65-year old woman. Volume loss and loss of the philtrum are more advanced and vertical rhytides are more pronounced. Repairs are often less visible

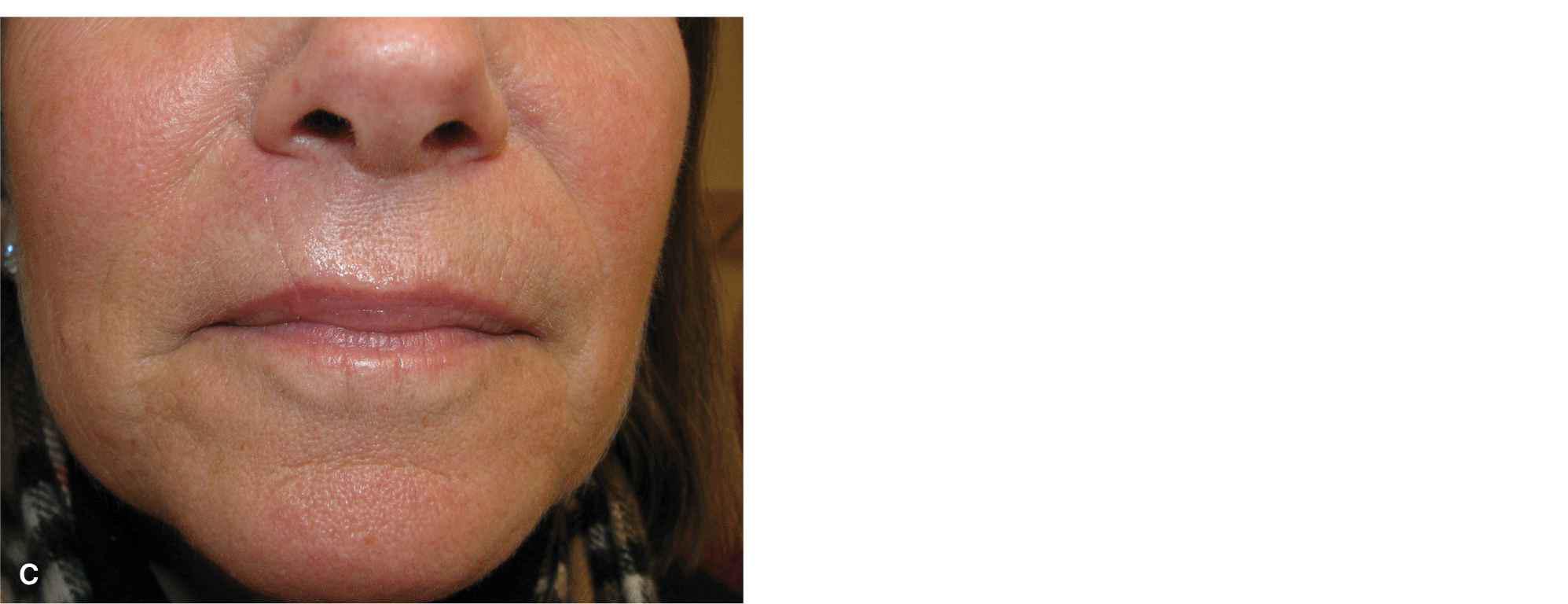

There is tremendous variation in the shape of the perioral region, and this has an impact on reconstruction (Fig. 9.5). Some individuals have a small oral opening, while others have a broad, wide mouth. The upper lip may be high and arched, or low and flat. The distance from the columella to the vermillion varies dramatically from person to person, as does the span from commissure to commissure. While most younger individuals have a prominent philtrum, in some it is minimal even in youth. In some older individuals, there is no residual philtrum at all. Such variation has impact on operative reconstruction, as what may be a simple repair in some individuals can be a challenge in others.

Figure 9.5 Variations in size and configuration of the mouth/lips. (A) Small oral aperture. Loss of any substantial component of the oral diameter may lead to relative microstomia. (B) A broad upper and lower lip makes reconstruction easier in the event of a sizeable defect

This chapter focuses on the aesthetic and functional repair of modest wounds of the upper and lower lip. A storied history of reconstruction of the lip for large wounds dates to the late 1500s and involves some of the great plastic and oral surgeons. While generally beyond the scope of this text, the artistry and geometry involved in the history of extensive wound lip reconstruction is well worth examining.2

UPPER LIP

Lateral Subunits

The lateral subunit of the upper lip is bounded by the nasolabial fold, the alar crease, the philtrum, and the vermillion border. Nonmelanoma skin cancer of the upper lip is very common, and hence repair of the upper lip lateral subunit is a frequent reconstruction.

Linear repairs

Small and modest wounds of the mid upper lateral subunit may be repaired linearly (Fig. 9.6). Vertical lines on the lip are common with age. With proper execution, such repairs can be highly aesthetic and lead to minimal or no functional impairment. The most appropriate wounds for a linear repair are those which lie above the vermillion border and whose vertical axis is longer than the horizontal axis. Linear repairs on the lip do not need to be exactly vertical. They generally should parallel the philtral columns medially but remain perpendicular to the vermillion border as it arcs slightly with its lateral procession. Linear repairs on the lip must be long and should be carried right through the vermillion border.3 In most cases, the outermost orbicularis band should be transected and excised as a “mini wedge,” without which a standing pucker of lip will often exist (Figs. 9.7 and 9.8). Dog-ears on the lip do not recede, and therefore the repair must be long enough and deep enough (just above orbicularis) to ensure that it lies flat at the moment of closure. In addition, the vermillion must be meticulously reapproximated. Even mismatch of a millimeter or less of vertical height will create a visible deformity and ruin what may otherwise be a nearly invisible repair.

Figure 9.6 For modest wounds of the lip, a vertical linear closure is an excellent repair. (A) A vertically oriented wound on the lip and a linear repair design for closure. (B) The closure is long and passes right through the vermillion border in order to avoid a pucker at the inferior margin. (C) Final result at 1 year with aesthetic repair

Figure 9.7 Fullness and puckering of the vermillion following a vertical linear repair. This is particularly problematic when smiling, as it shows against the teeth. This can be avoided in most cases with proper planning and technique. (A) Immediate linear repair on the lip showing fullness and “bulldozing” of the upper lip vermillion. This can be avoided by removing the distal orbicularis oris band. (B) Photo at 6 months demonstrating resolution of most puckering, but still some fullness of the lip

Figure 9.8 A slightly larger wound on the upper lip is repaired with a linear closure in which the distal/surface band of orbicularis oris is removed. (A) Operative wound. (B) The repair is performed in the potential space above the orbicularis musculature and is extended right through the vermillion border. The distal/surface band of orbicularis is excised and repaired as a “mini-wedge.” (C) Immediate closure without pucker formation. (D) Aesthetic closure healing at 3 months

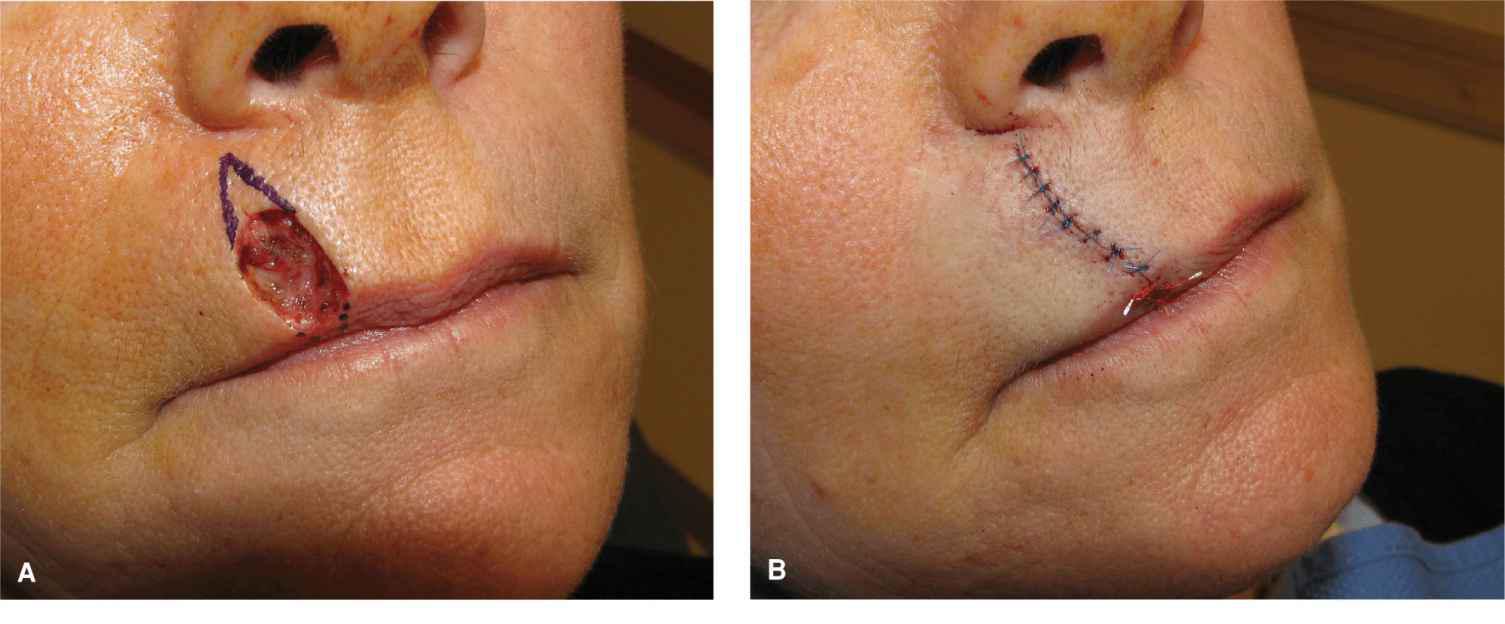

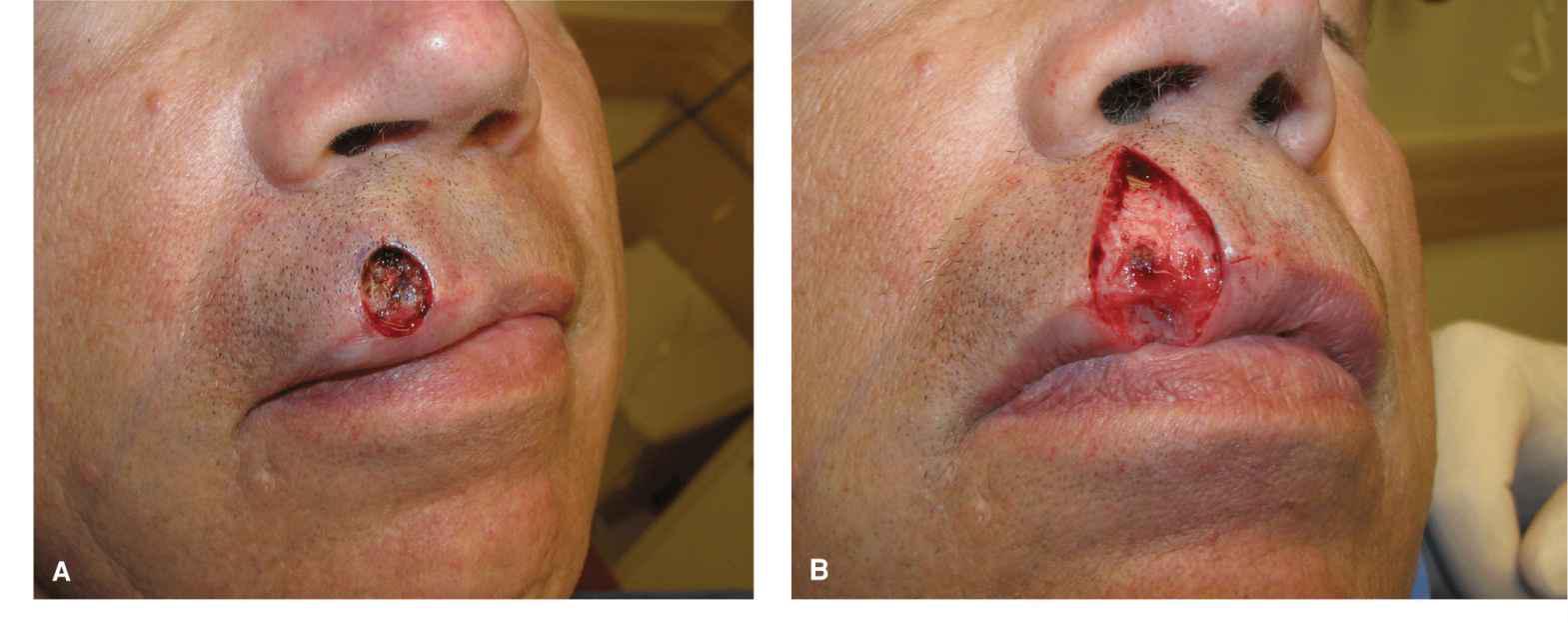

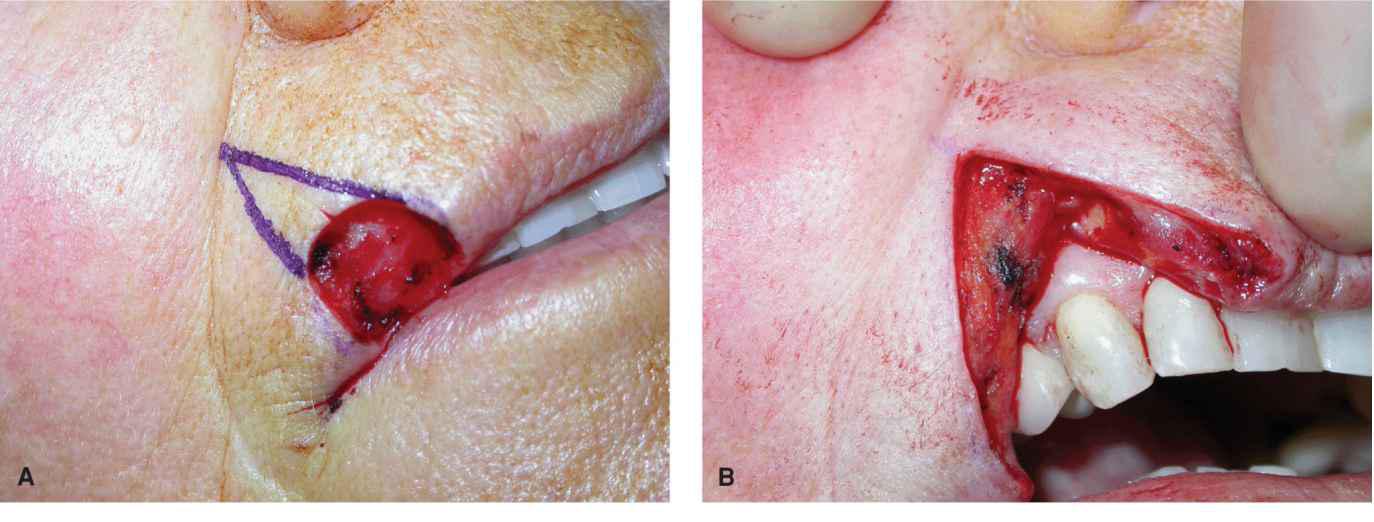

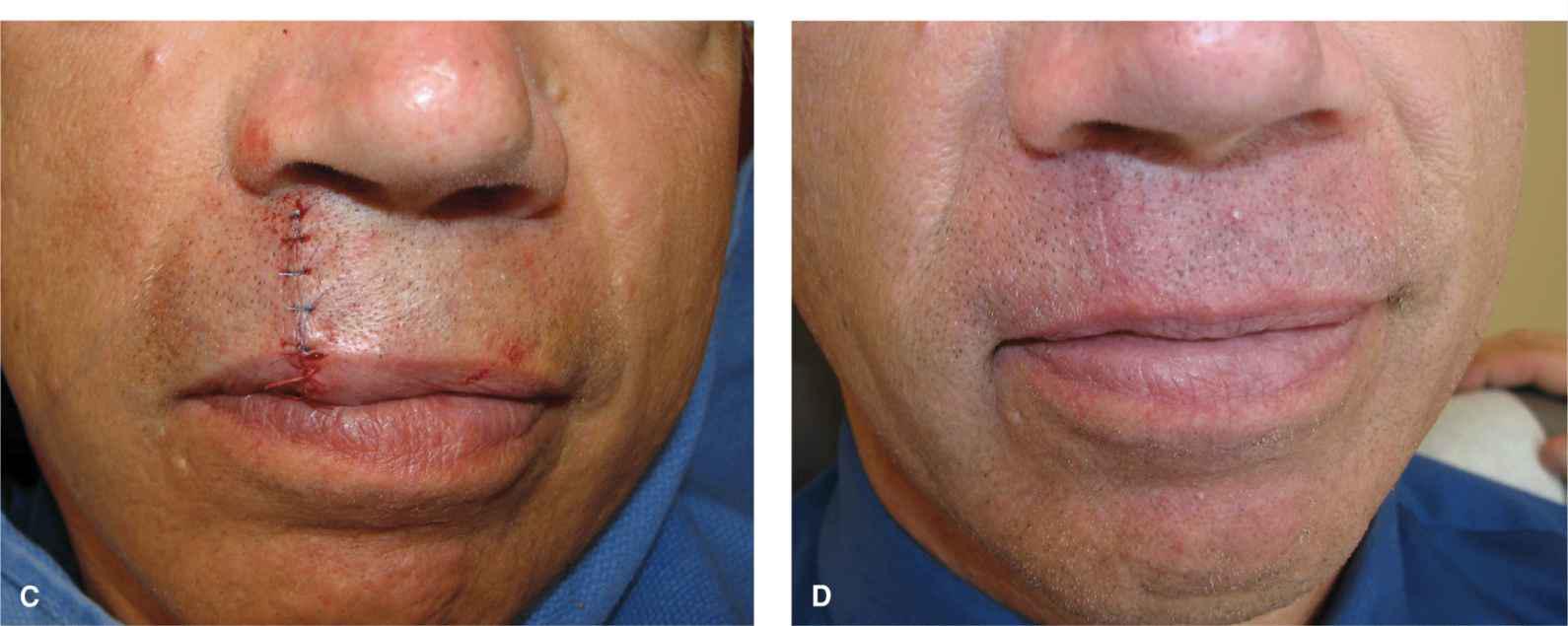

Lip wedge

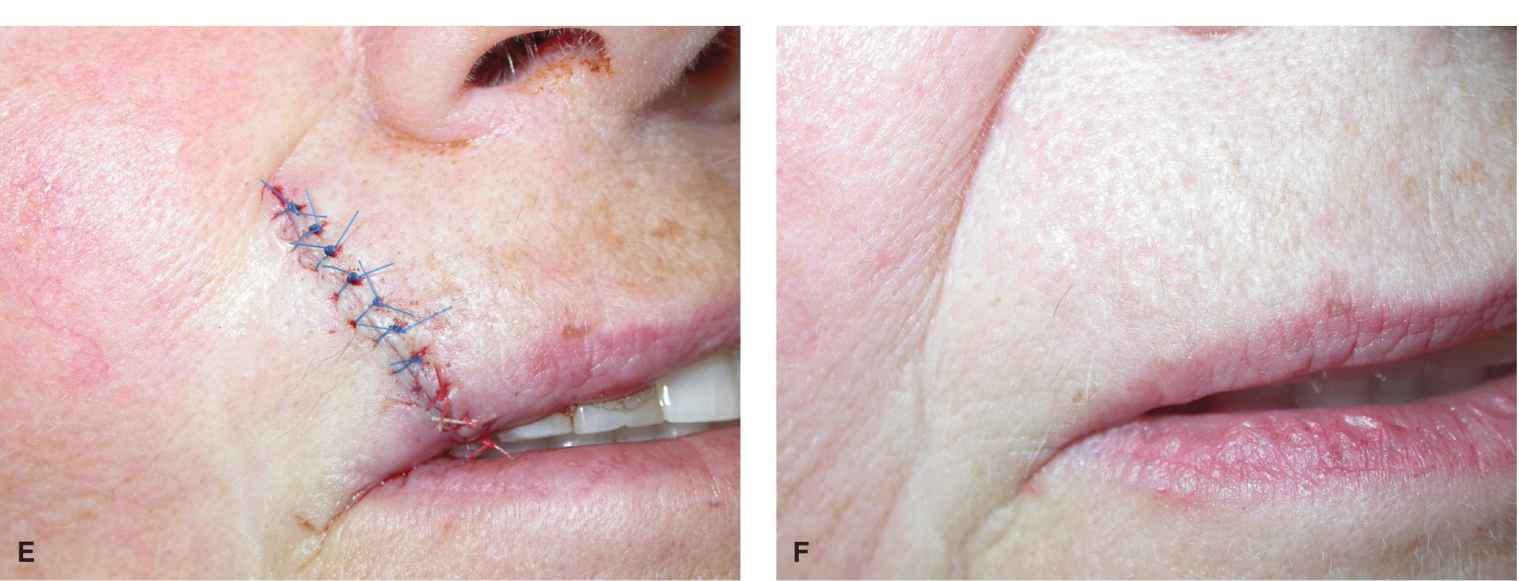

Wounds involving the vermillion border of the lateral upper lip are common. Many such defects can be repaired with a full-thickness or modified full-thickness wedge reconstruction (Fig. 9.9).4 As originally defined, the wedge is a full-thickness V-shaped transmural repair. The operative wound edges are squared off and a full-thickness V-shaped “pie” of tissue is excised up to the gingival sulcus. The labial artery is either ligated or electrocoagulated, and the repair is then closed in a multilayer fashion. The mucosa is first closed with an absorbable suture such as chromic gut. The muscle is then reapproximated with an absorbable buried suture, the dermis is separately repaired, and then the epidermis and vermillion mucosa are reapproximated.

Figure 9.9 A modest wound of the lateral upper lip and vermillion is repaired with a wedge. (A) Operative wound and planned wedge. (B) A full-thickness excision has been accomplished. (C) The mucosa has been repaired. (D) The orbicularis oris has been reapproxi-mated. (E) Repair at completion with careful matching of the vermillion border. (F) Repair at 6 months

As with the simple partial-thickness closures, it is imperative to carefully match the vermillion borders. If the defect is broad and the lip narrow, a wedge will lead to a mismatch between the smaller lateral cutaneous lip and vermillion and the taller, more substantive medial remnant. The result will be a functional lip but a visible mismatch. This may be a tolerable deformity but should be considered if the patient has high cosmetic expectations. Also, a wedge reconstruction of any defect that encompasses more than one quarter of the upper lip has the potential to cause microstomia, and for larger wounds, rotational flaps and lip sharing procedures may be preferred. The advantage of a lip wedge is that it is a relatively nonmorbid repair with a low risk of complications. Like partial-thickness repairs, wedges need not be entirely vertical but should be precisely perpendicular to the vermillion border they will repair.

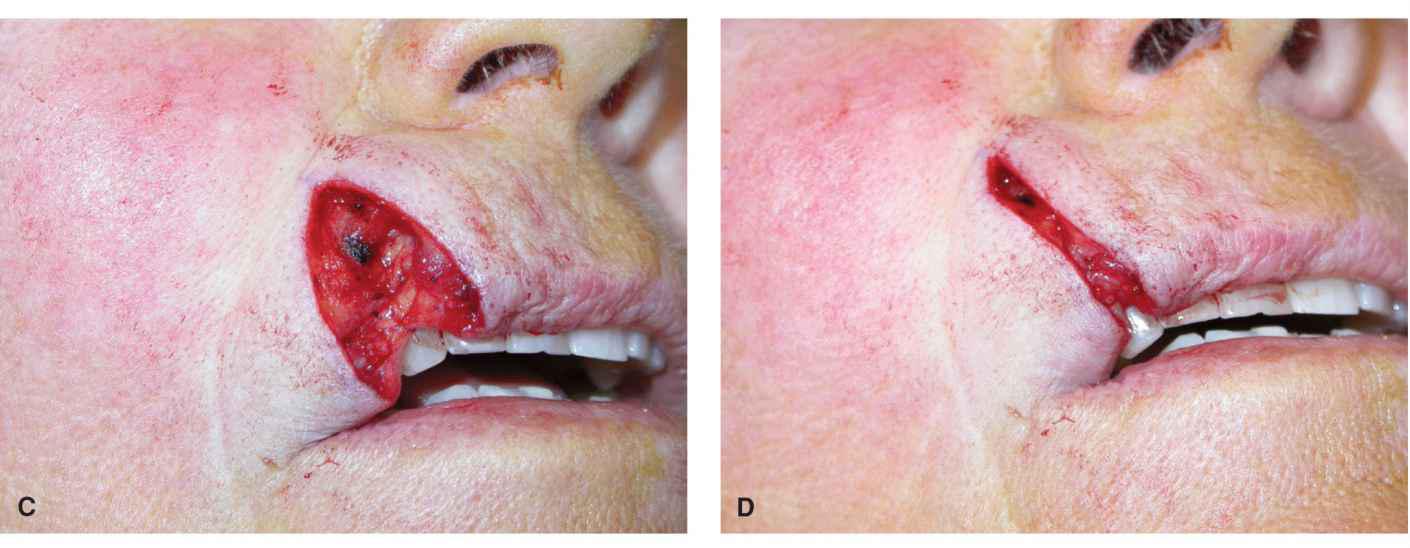

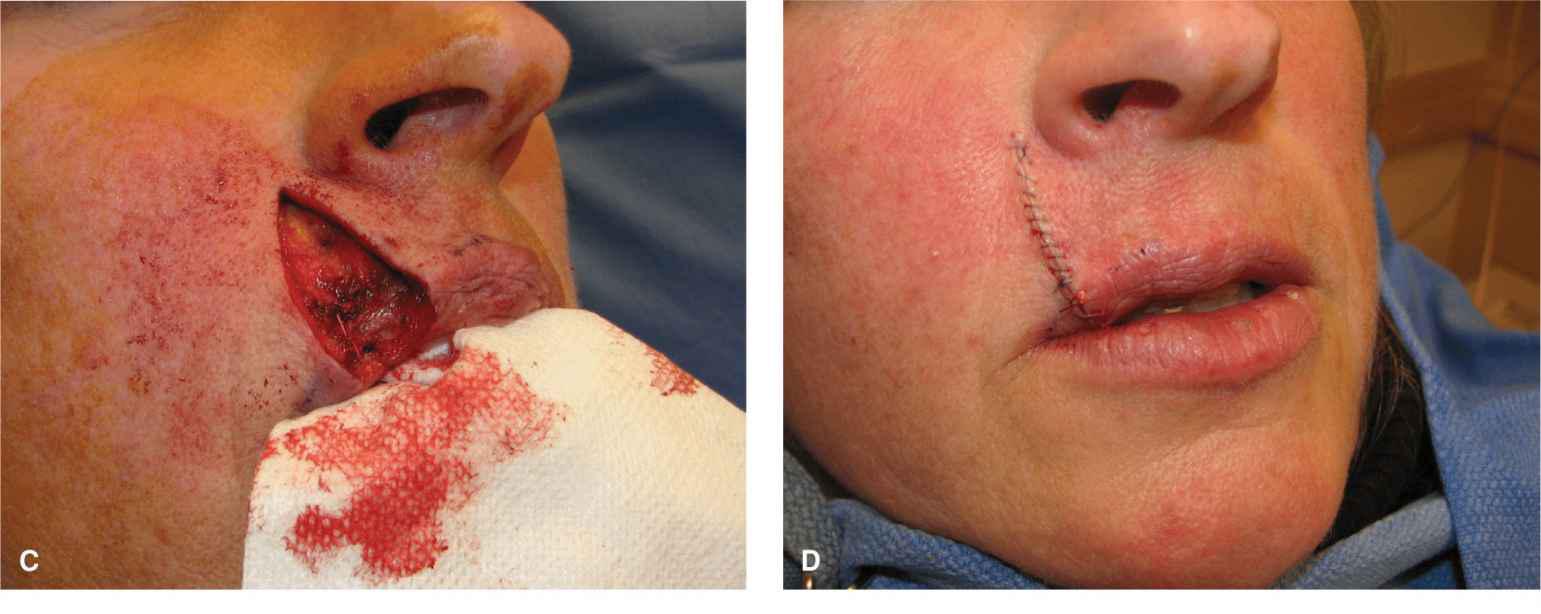

A modification of the lip wedge avoids extending the repair all the way to the gingival sulcus and preserves some muscle (Fig. 9.10).5 In the modified technique, the external repair is extended the full vertical height of the lip, but the internal extent is only about 50% of the height of the lip. The distal band of orbicularis is completely severed as is the labial artery, but the larger, deeper major circumoral band of orbicularis is preserved. This repair is less extensive than the full-thickness wedge and may preserve a more normal circumoral muscle tone in the postoperative period. From an aesthetic standpoint, there seems to be little difference from the standard lip wedge.

Figure 9.10 A modified wedge repair is performed as a partial-thickness closure without extension all the way to the gingival sulcus. (A) Operative wound and planned repair. (B) The wedge has been accomplished by excising the entire vermillion and all of the distal bands of the orbicularis oris. The labial artery has been ligated and transected. The upper bands of the orbicularis are preserved, and the wound edges are undermined free of the muscle. (C) The repair is closed by repairing the mucosa and the distal orbicularis band. (D) Immediate result without lip distortion. (E) Aesthetic repair at 6 months

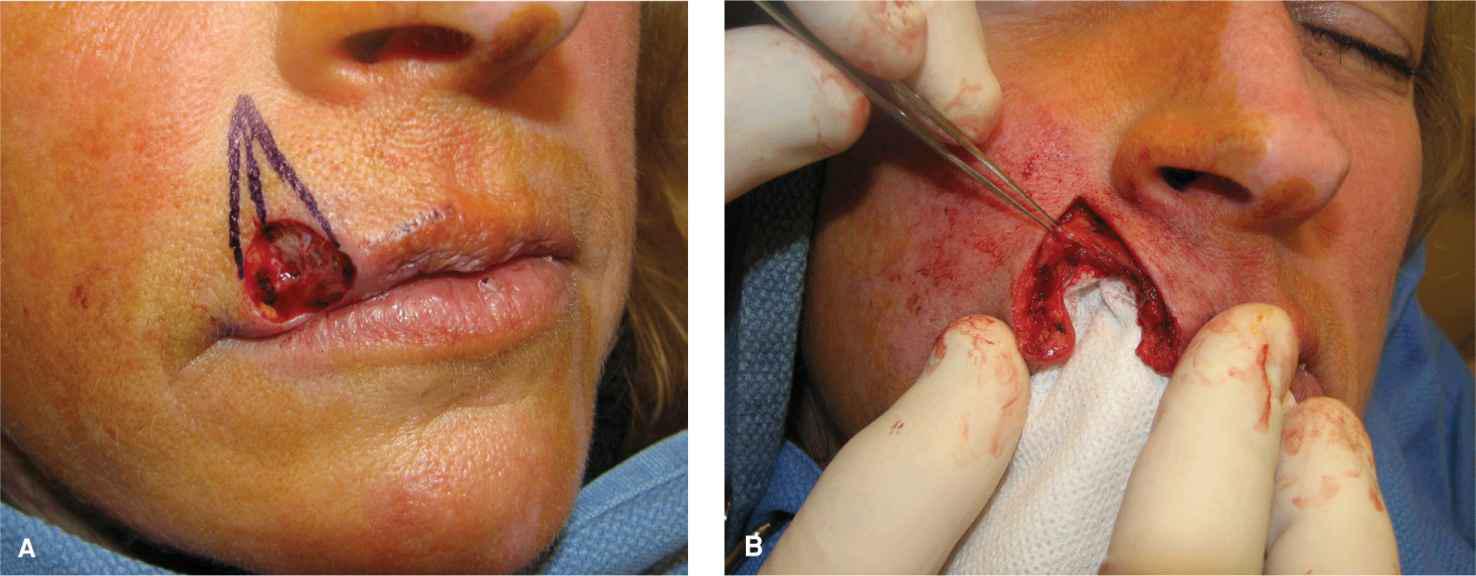

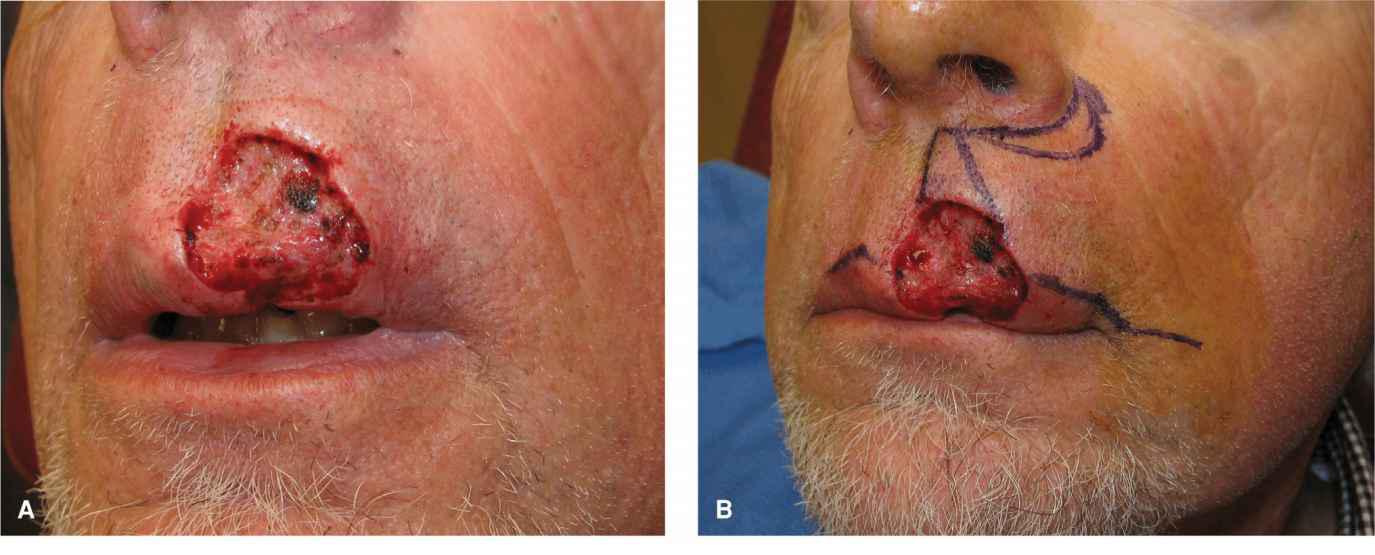

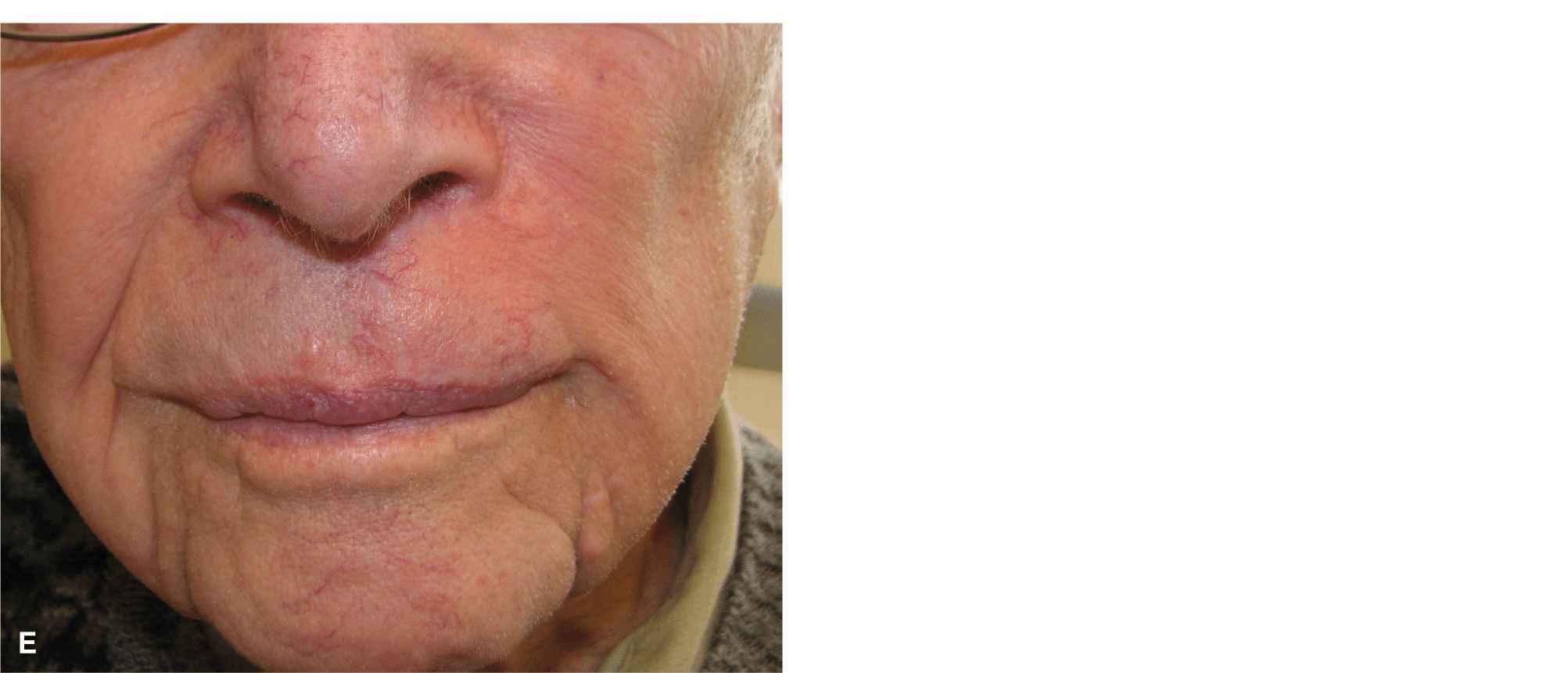

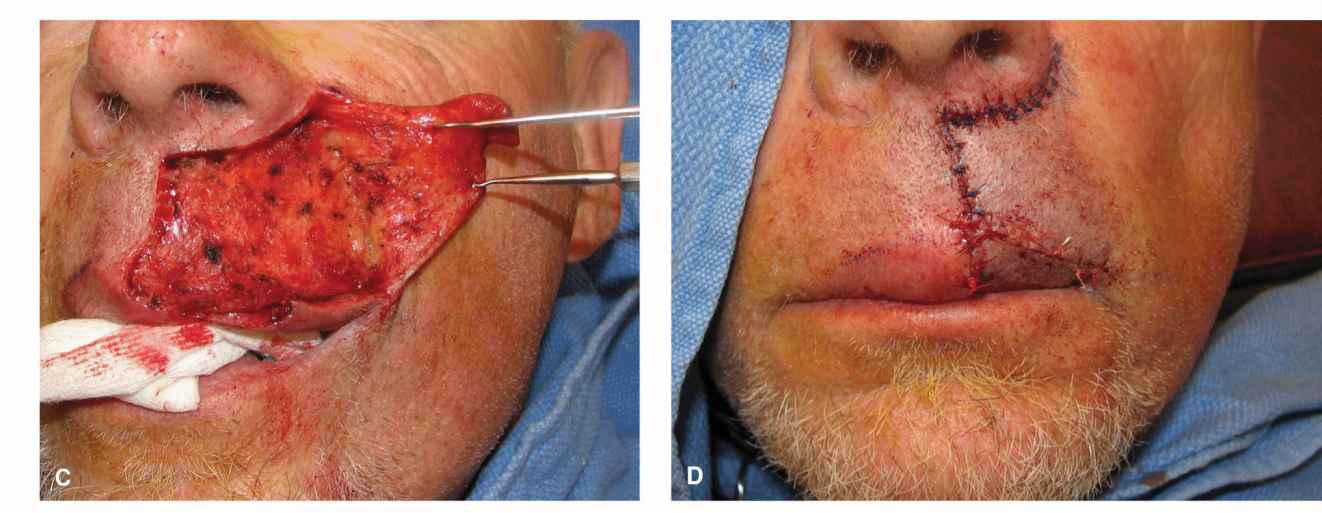

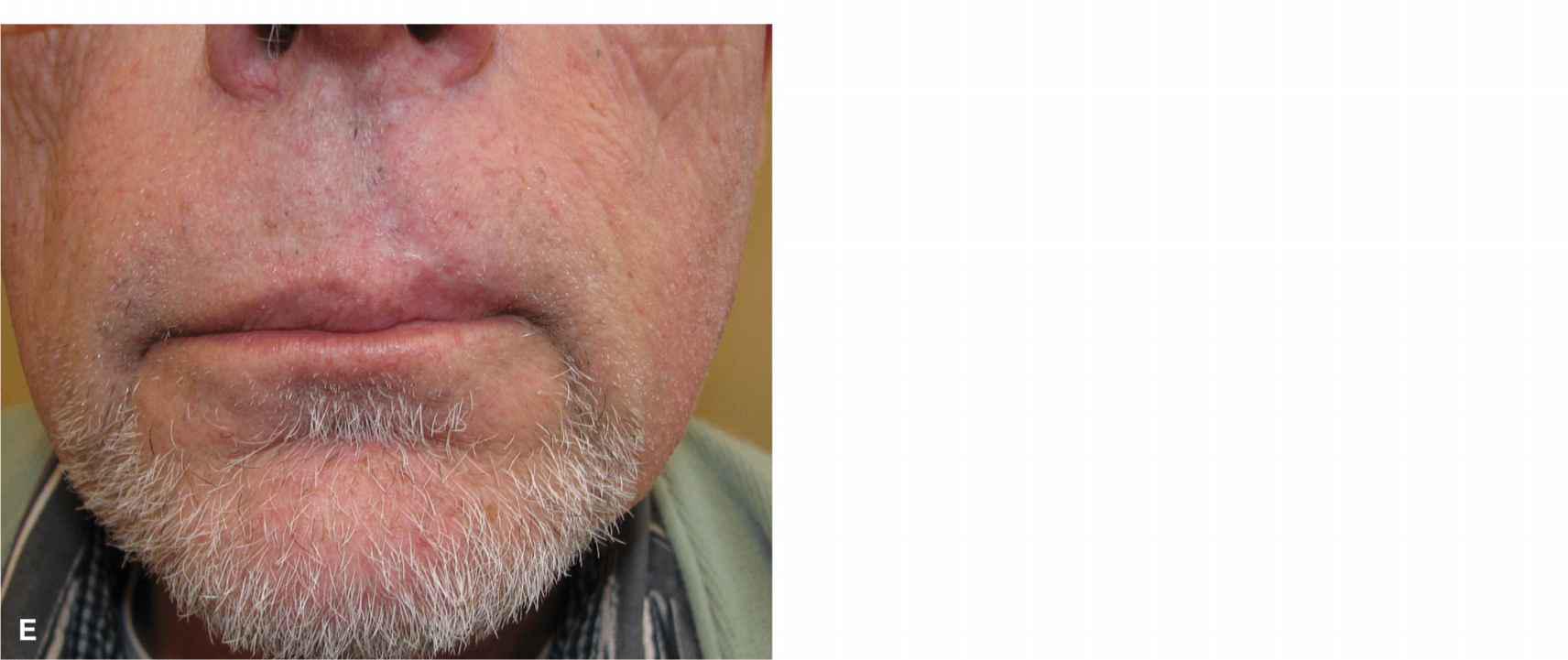

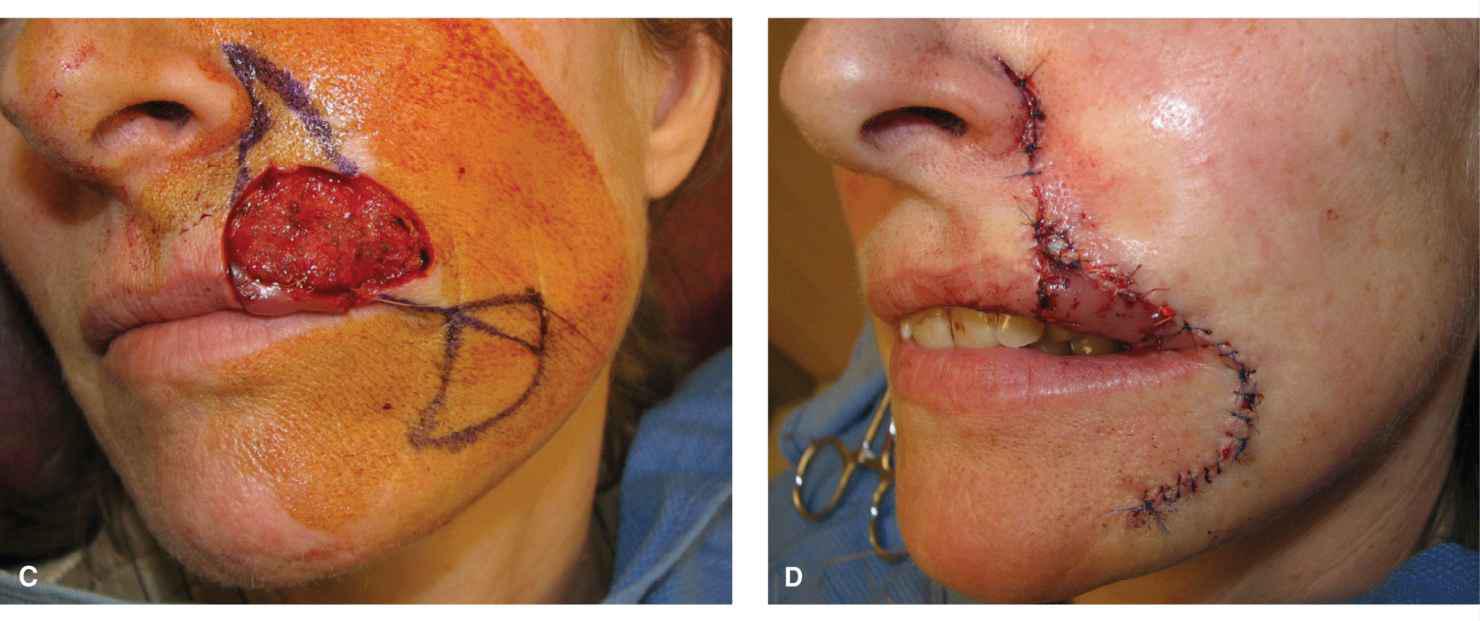

Advancement

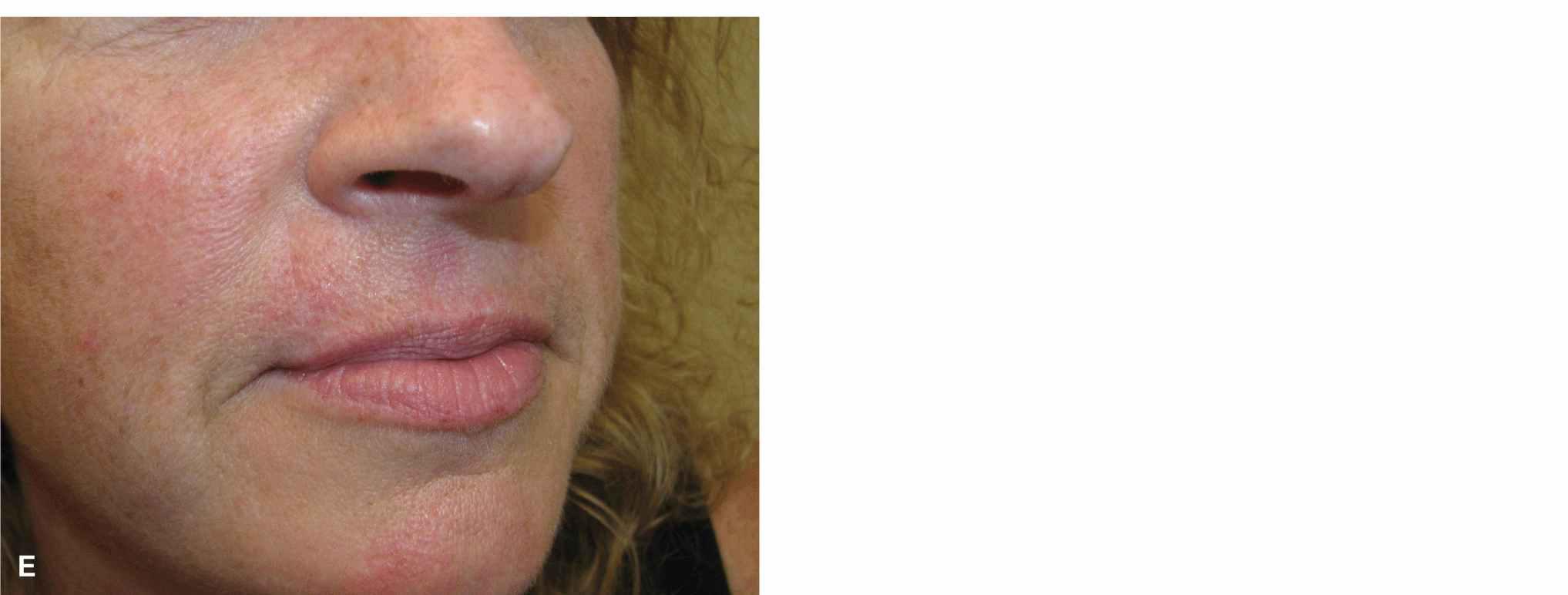

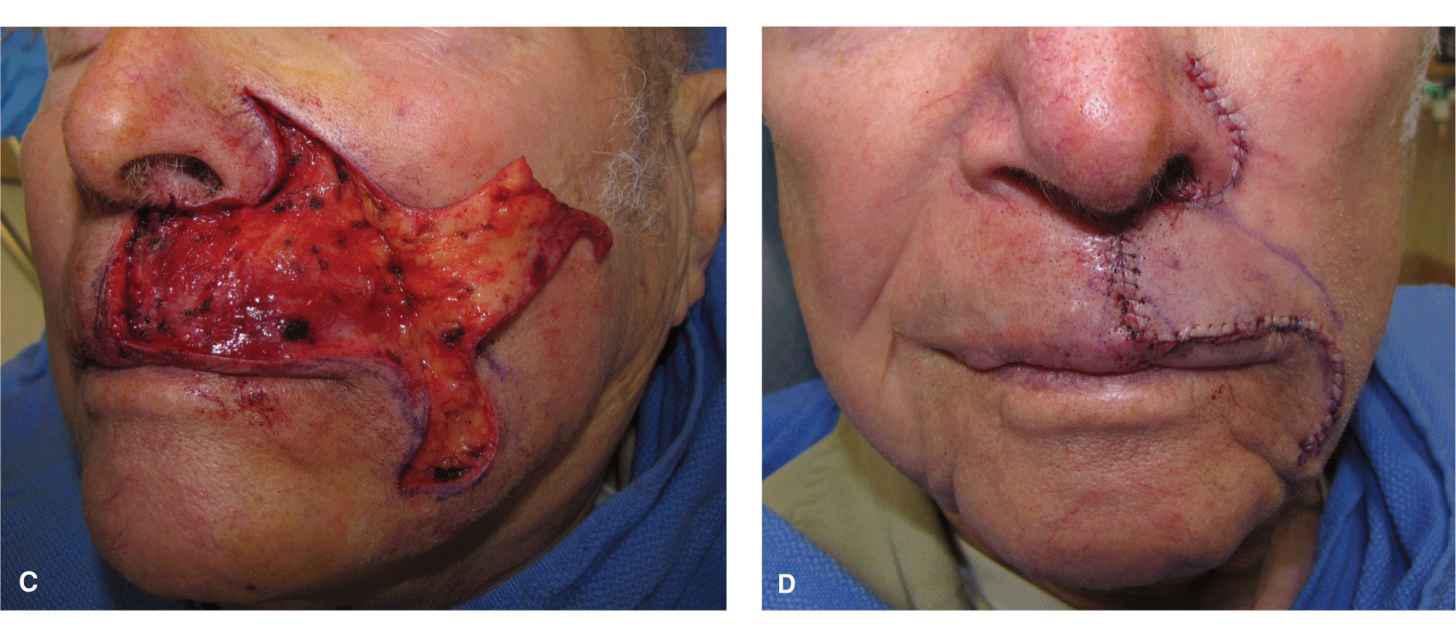

Many moderate-to-large cutaneous wounds of the upper lip lateral subunit can be suitably repaired with unilateral advancement flaps (Figs. 9.11–9.13).3,6–8 These large repairs use laxity from the medial cheek to allow for a nearly tension free closure on the lip, thus avoiding phil-tral and vermillion distortion.

Figure 9.11 Figure and photos demonstrating a cheek advancement for a sizeable operative wound on the medial aspect of the lateral subunit. (A) Operative wound. A linear repair or wedge would distort the lip and displace the philtrum. A graft would be highly unaesthetic. (B) A large advancement flap is designed with a crescentic standing tissue cones to be removed around the ala and lateral to the oral commissure. (C) The flap is elevated above orbicularis. This is an area with rich vasculature, and precise hemostasis is essential. (D) Immediate closure. The most challenging aspect of this repair is judging the effect of the advancement on the position of the lateral upper lip/vermillion. (E) Repair at 6 months demonstrating normal form and function and excellent cosmesis (Photos courtesy of Dr. Todd Holmes.)

Figure 9.12 In a modification of the prior repair, a large upper lip wound is repaired with a cheek advancement and a separate vermillion advancement. (A) A large operative wound might be repaired with a lip wedge, but the patient is a tuba player and wishes to maintain his ombusure. (B) Advancement is designed to tap into laxity of the medial cheek. A crescentic standing tissue cone is delineated around the alar margin. (C) The flap is elevated out to and beneath the nasolabial fold. (D) The repair at completion. The vermillion has been undermined and advanced/rotated separately. (E) Repair at 9 months demonstrating mild asymmetry.

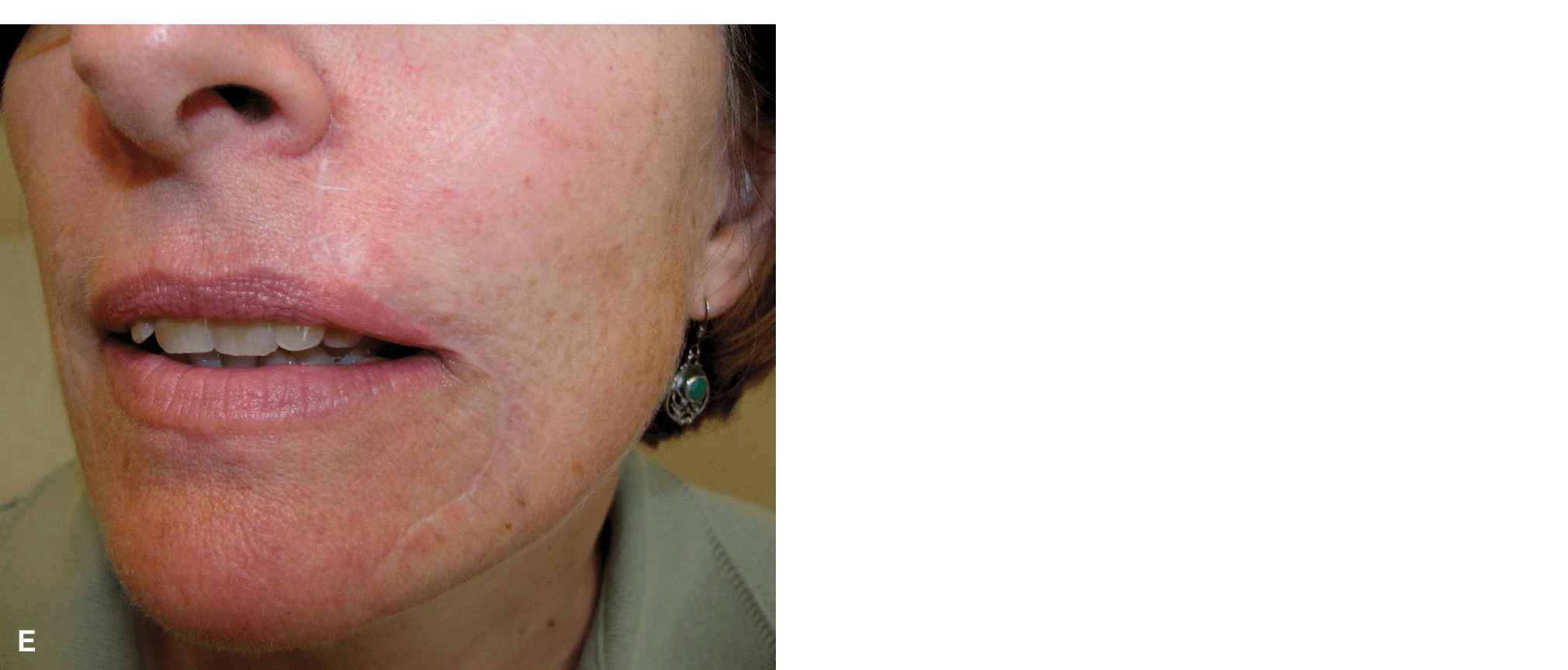

Figure 9.13 A large defect of the left upper lip is repaired with a cheek advancement and a mucosal island pedicle flap. (A) Operative wound encompasses much of the lateral subunit and includes a mucosal defect. (B) The mucosal wound has been repaired with a mucosal island flap. (C) Advancement planned. (D) The flap has been advanced into place. (E) Final result at 1 year demonstrates normal lip contour. There was some tension on this repair, and the scars are visible and hypopigmented

For defects near the vermillion, a standing tissue cone is removed superiorly and a broad flap is advanced from the lateral lip and medial most cheek. The design includes an inferior base which parallels the vermillion border just a millimeter above it and extends lateral to the oral commissure, where a standing tissue cone is removed as the flap advances. The flap is elevated in the potential plane just above the orbicularis oris, and when the nasofacial sulcus is reached, a reservoir of freely mobile tissue is achieved, thus freeing essentially all pivotal restraint. The flap should not be bulky and in general does not include any muscle fibers. The pedicle is from the superolateral aspect of the flap, and freed from all lip restraints, it may be advanced without distortion of the lateral vermillion. It is essential that all tensions are directed in a horizontal plane. Substantial attention to detail is required to ensure appropriate positioning of the lateral lip to avoid any tension on or depression of the ipsilateral vermillion. If in doubt, it is better to have the lateral commissure slightly depressed rather than elevated, as this is easier to correct in follow-up. In most cases, the strong musculature of the perioral region will reestablish the position of the mouth within several months such that prolonged positional distortion is rare, but every effort should be made to have a tensionless closure.

For defects closer to the nose or for very large defects of the upper lip, a modified advancement flap includes an arciform standing tissue cone that extends up and around the nasal ala and alar crease. By extending the repair superiorly and around the ala, the entire medial cheek can be mobilized and even extensive lip wounds can be suitably repaired. In elevating such flaps, it is important to avoid transferring a deep, bulky flap onto the upper lip. The base of the flap is broad, and the blood supply is reliable. As such a relatively thinner flap may be advanced with confidence. Even appropriately thin upper lip advancements tend to pincushion for a period of several months, but as a rule they will eventuate in an aesthetic repair. Thicker flaps without adequate undermining and improper sizing will remain bulky and unsightly as a finger of tissue seemingly placed onto the lip, and in these cases, revision is needed.

All upper lip advancements have an impact on the nasolabial fold, and asymmetry is a consequence. The aesthetic compromise of an absent nasolabial fold is usually offset by repair of a more important location, namely the upper lip, but this expectation should be discussed with the patient prior to repair.

Rotation

Rotation flaps are niche repairs on the upper lip but can prove exceptionally valuable in the appropriate situation (Fig. 9.14).9 Defects amenable to rotation are small-to-moderate wounds of the lateral subunit in the perialar region. Such wounds are often repaired with island pedicle flaps (see later). If the wound is repaired linearly, the superior standing tissue cone removal compromises the apical triangle of the lip. The ideal candidate is a patient with a relatively high and broad upper lip and a prominent arciform nasolabial fold. The repair is designed by dropping a standing tissue cone from the wound to the vermillion border. The arc of rotation extends along the nasolabial fold. The flap is elevated above muscle and all the way to the vermillion border. In this rotation, tension is directed in large part along the primary tension vector, and the rotation is used to eliminate tissue redundancy. The rotated arc can generally be sewn out along the nasolabial fold without removal of a dog-ear. It is important only to utilize this repair when the wound is relatively small in relation to the size of lateral subunit. If there is too much rotational torque on the flap, the lateral vermillion can be elevated, thus resulting in a sneer appearance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree