17 Laparoscopic Surgery for Stress Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse

LAPAROSCOPIC RETROPUBIC SURGICAL PROCEDURES

In the first report, Vancaillie and Schuessler (1991) laparoscopically duplicated the conventional Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz (MMK) procedure. Subsequently, Albala et al. (1992) published a case series of MMK and Burch procedures. Many investigators have modified the laparoscopic retropubic colposuspension using varying numbers and types of suture, synthetic mesh, staples, bone anchors, coils, tacks, fibrin sealant, and radiofrequency. Various suturing and needle devices have been used to simplify laparoscopic suturing and knot-tying, the most difficult skills to acquire.

Indications

After the patient has been diagnosed with urodynamic stress incontinence and has opted for surgical management, the choice of laparoscopic versus open retropubic colposuspension depends on numerous factors: history of previous pelvic or anti-incontinence surgery; history of severe abdominopelvic infection or known extensive abdominopelvic adhesions; patient age and weight; ability to undergo general anesthesia; need for concomitant abdominal, pelvic, or vaginal surgery; patient preference; and operator experience and preference. To date, most laparoscopic colposuspensions have been done for only primary stress incontinence because of difficulty in dissecting retropubic adhesions. Many patients choose laparoscopic surgery because of the smaller, more cosmetic incisions, shorter recuperation time, and rapid return to work. We explain to our patients that we perform the same procedure open and laparoscopically and that it is only the route that differs. We also state that the procedure outcomes appear to be comparable to open techniques in our hands based on short-term follow-up.

Anatomy

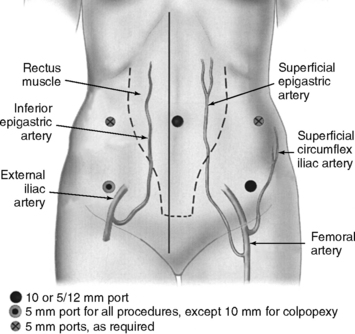

The superficial epigastric artery, a branch of the femoral artery, courses cephalad and can be transilluminated. The inferior epigastric artery branches from the external iliac artery at the medial border of the inguinal ligament and runs laterally to and below the rectus sheath at the level of the arcuate line. Two inferior epigastric veins accompany this artery (Fig. 17-1). The median umbilical ligament, the embryonic urachus, is attached to the apex of the bladder and extends to the umbilicus. The urachus remains patent in some women and may be somewhat vascular. The medial umbilical folds, the peritoneum overlying the obliterated umbilical arteries, are the lateral landmarks of dissection of the parietal peritoneum during transperitoneal surgery into the space of Retzius. The upper margin of the dome of the bladder is noted approximately 3 cm above the pubic symphysis when the bladder is filled with 300 mL of fluid. Before distention of the bladder, the upper margin of the dome lies several centimeters above the pubic symphysis.

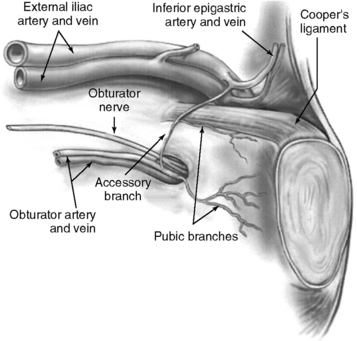

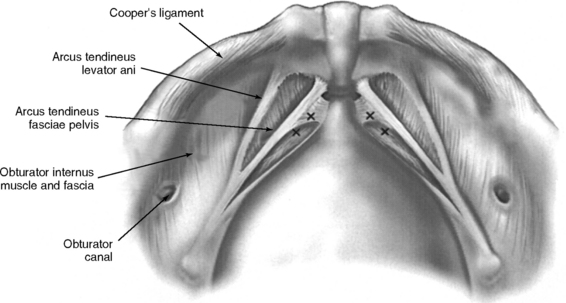

The important landmarks of the space of Retzius are Cooper’s ligaments; the accessory or aberrant obturator veins; the obturator neurovascular bundles, which are 3 to 4 cm above the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis; the bladder neck, which is delineated by placing traction on the Foley bulb; and the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis and arcus tendineus levator ani, which insert into the pubic bone (Figs. 17-2 and 17-3).

Operative Technique

OPERATIVE SETUP AND INSTRUMENTATION

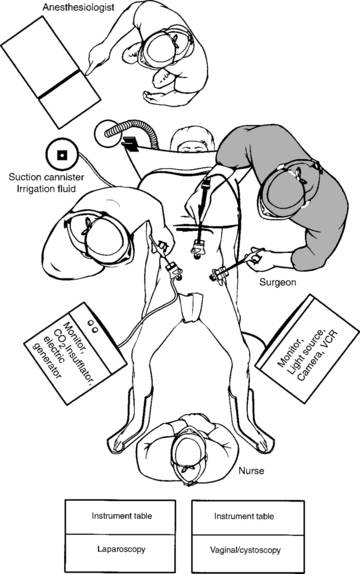

The operating room setup is shown in Figure 17-4. The monitor screens should be placed laterally to the legs in direct view of the surgeon standing on the opposite side of the table. The scrub nurse should be in the center if two monitor screens are used; otherwise, the scrub nurse is located behind one surgeon and the electrosurgical unit or harmonic scalpel on the opposite side. After the three-way Foley catheter and uterine manipulator (if needed) have been placed, the vaginal tray with cystoscope is set aside, if desired, for later use.

Ideal stirrups for combined laparovaginal cases are the Allen stirrups and Yellofins (Allen Medical Systems, Acton, MA) that have levers that can quickly convert the patient from low to high lithotomy position while preserving sterility of the field. A sterile pouch attached to each thigh is equipped with commonly used instruments, such as unipolar scissors, bipolar cautery, graspers, and laparoscopic blunt-tipped dissectors. The irrigation should be set up before making incisions for trocars.

SKIN INCISIONS FOR TROCAR SITES

Intraumbilical or infraumbilical incisions are made depending on the anatomy of the umbilicus. Many variations of the accessory trocar sites have been described. We use two additional trocars: a 5/12-mm disposable trocar with reducer in the right lower quadrant (if knot-tying from the right) lateral to the right inferior epigastric vessels and a reusable 5-mm port or an additional 5/12-mm disposable trocar, with reducer in the left lower quadrant lateral to the left inferior epigastric vessels. Trocars are placed laterally to the rectus muscle, approximately 3 cm medial to and above the anterior superior iliac spine. Based on an anatomic study by Whiteside et al. (2003), we know that ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve entrapment during fascial closure may be reduced if the ports are placed at least 2 cm cephalad to the anterior superior iliac spines. An additional 5-mm port may be placed on the principal surgeon’s side so that he or she can operate with two hands. Both reusable and disposable ports may be secured with circumferential screws to prevent port slippage. Versa Step Plus trocars (U.S. Surgical Corp., Norwalk, CT) allow easy introduction of needles, maintain pneumoperitoneum during extracorporeal knot-tying, and prevent port slippage because of the expandable sleeve. Port placement is shown in Figure 17-1.

LAPAROSCOPIC BURCH COLPOSUSPENSION

After the space of Retzius is exposed, the surgeon places two fingers in the vagina and identifies the urethrovesical junction by placing gentle traction on the Foley catheter. With elevation of the vaginal fingers, the vaginal wall lateral to the bladder neck is exposed by using a laparoscopic blunt-tipped dissector. As recommended by Tanagho (1976), no dissection is performed within 2 cm of the bladder neck to avoid bleeding and damage to the periurethral musculature and nerve supply.

We place stitches in the vaginal wall, excluding the vaginal epithelium at the level of, or just proximal to, the midurethra and bladder neck (see Fig. 17-3). No. 0 nonabsorbable suture is placed in a figure-of-eight stitch incorporating the entire thickness of the anterior vaginal wall. The needle is then passed ipsilaterally through Cooper’s ligaments. If double-armed suture is used, we make two passes through Cooper’s ligaments and subsequently tie above the ligaments. We place Gelfoam (Pharmacia Upjohn, Inc., Kalamazoo, MI) between the vaginal wall and the obturator fascia before knot-tying to promote fibrosis. With simultaneous vaginal elevation, the suture is tied with six extracorporeal square knots. Two granny half-hitches (equivalent to a surgical knot) and a flat square knot secure the stitch. Our technique for laparoscopic Burch procedure is illustrated in Color Plate 3.

Sutures are tied as they are placed to avoid tangling. Midurethral stitches are placed first, although this is a matter of preference. Placing stitches from the contralateral port is easier. For example, a right-handed surgeon elevates the vagina with his or her left hand while simultaneously placing stitches on the patient’s right side through the lower left port. In this circumstance, the principal surgeon must switch sides with the assistant. If the lower quadrant ports are placed higher (at or slightly below the level of the umbilicus), placement of ipsilateral stitches is facilitated because the angle to the ipsilateral vaginal wall and Cooper’s ligaments is less acute. The appropriate level of bladder neck elevation is estimated with the assistant’s vaginal hand. The assistant elevates the vaginal wall to place the urethra and bladder neck in a high retropubic position, which does not result in kinking or compression of the urethra. The goal is to elevate bilaterally the vaginal wall to the level of the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis so that the bladder neck is supported and stabilized by the vaginal wall that acts as a hammock between both “white lines.” In tying the sutures, the surgeon should not reapproximate the vaginal wall to Cooper’s ligaments or place too much tension on the vaginal wall. A suture bridge of 1.5 to 2 cm is common.

LAPAROSCOPIC PARAVAGINAL DEFECT REPAIR

Starting at the vaginal apex, a No. 2–0 nonabsorbable, 36- or 48-inch suture on a CT-2 needle is used to place a stitch into the full thickness of the vagina (excluding the vaginal epithelium) and then into the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis, which is 3 to 4 cm below the obturator fossa (Color Plate 4). This is then tied extracorporeally. An additional three to five sutures are placed through the vaginal wall and into the arcus tendineus or fascia of the obturator internus muscle at 1- to 2-cm intervals until the defect is closed. The same procedure is performed on the opposite side.

Clinical Results and Complications

Numerous case series have reported laparoscopic Burch colposuspension with conventional suturing technique (Table 17-1). Liu (1994) reported the first large series; 132 patients were followed for 3 to 27 months with a 97% cure rate (completely dry) and 10% complication rate (4 bladder injuries, 4 patients with urinary retention, 1 with ureteral obstruction, 3 with detrusor overactivity, and 1 with gross hematuria caused by insertion of a suprapubic catheter). Continence rates among studies vary from 69% to 100%. Five of 14 studies reported objective data. Total operative time varied from 35 to 330 minutes, with means ranging from 90 to 196 minutes. Most authors reported less blood loss, shorter hospitalization, and less frequent postoperative voiding dysfunction and de novo detrusor overactivity when compared with the abdominal route. As a preliminary observation, many authors reported decreased incidence of urinary retention and detrusor overactivity associated with laparoscopic Burch. Reasons for less-frequent postoperative voiding dysfunction are unknown, and possible explanations include sutures not being tied as tightly, which is intentional or unintentional, as a result of technique variables; less dissection of the periurethral and paracolpium tissues by some surgeons; and less postoperative pain associated with smaller incisions. The largest series of laparoscopic Burch colposuspension for primary urodynamic stress incontinence was reported by Lee et al. (2001). With only 10 patients lost to follow-up at an average of 46 months (range 36 to 60), the authors reported a satisfaction rate of 96%. Complications included 3 (1.9%) bladder injuries that were repaired intraoperatively and 23 (15.3%) patients who required oxybutynin for detrusor overactivity. Moore et al. (2001) reported a 90% objective cure rate for recurrent stress urinary incontinence in 33 consecutive patients at 19 months average follow-up.