Introduction to diagnosing dermatological conditions (basic principles)

G Whitlock PhD, MRCP

John SC English FRCP

Iain H Leach MD FRCPath

Essentials of cutaneous anatomy and physiology

The skin is a large and specialized organ, which covers the entire external surface of the body. It plays an important role in protecting the body against external traumas and injurious agents such as infection, trauma, UV radiation, and extremes of temperature as well as providing waterproofing. Additional functions include detection of sensory stimuli and thermoregulation.

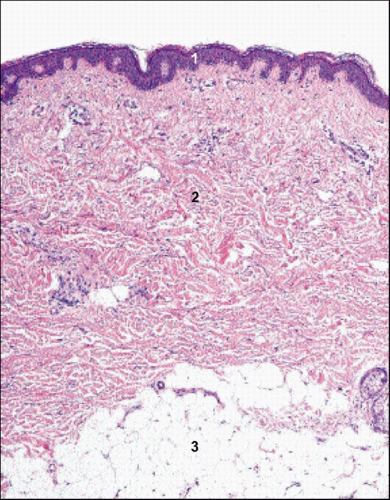

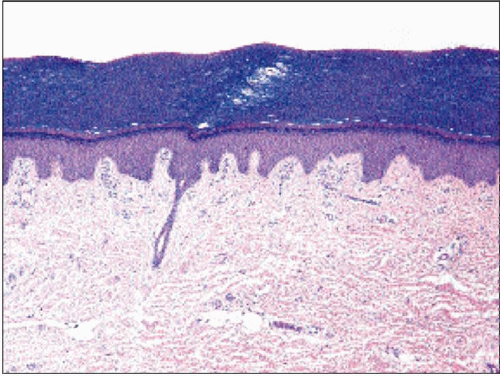

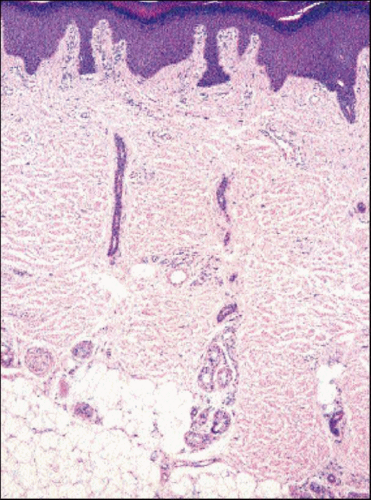

The skin has two main layers, the superficial epidermis and the dermis, which lies between the epidermis and subcutaneous fat (1.1). The microanatomy of the skin is essentially similar throughout, but there is considerable regional variation. For example, the surface keratin layer is much thicker on the palms and soles (1.2) than elsewhere, whilst the dermis is much thicker on the back than on the eyelids. There is also considerable regional variation in the numbers and size of skin appendages such as hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands.

The epidermis is the surface layer of the skin and is a keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium, the principle cell type being the keratinocyte. The basal layer of the epidermis contains small cuboidal cells that continually divide to replenish the cells lost from the skin surface. The bulk of the epidermis is composed of the stratum spinosum or ‘prickle cell’ layer, so called because the intercellular connections or desmosomes are visible on histological sections as prickles surrounding each cell. The cells in this layer are large with abundant cytoplasm containing keratin tonofilaments. With maturation towards the surface the cells become flatter and accumulate dark keratohyalin granules to form the granular layer. These cells then lose their nuclei and the keratohyalin granules, and keratin filaments

combine to form the surface keratin layer. Epidermal turnover is continuous throughout life, with the turnover time from basal cell to desquamation estimated at 30-50 days depending on site.

combine to form the surface keratin layer. Epidermal turnover is continuous throughout life, with the turnover time from basal cell to desquamation estimated at 30-50 days depending on site.

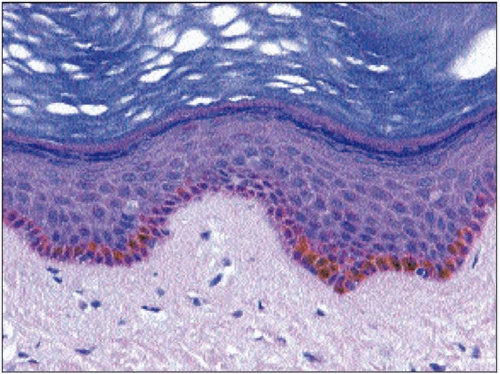

The epidermis also contains small numbers of melanocytes, Langerhans cells, and Merkel cells. Melanocytes are present scattered along the basal epidermis. They have long dendritic cytoplasmic processes, which ramify between basal keratinocytes. Melanocytes synthesize melanin pigment that is passed to basal keratinocytes via the dendritic processes in the form of granules or melanosomes. Melanin pigment varies in colour from red/yellow to brown/black. It is responsible for skin pigmentation and has an important role in protecting the skin from the effects of UV radiation. There is some regional variation in the number of melanocytes, with more being present on sun-exposed sites though the number is fairly constant between individuals. Racial skin pigmentation is related to increased activity and increased amounts of pigment rather than increased numbers of melanocytes (1.3).

Langerhans cells are also dendritic cells and are located in the basal epidermis and stratum spinosum. They act as antigen presenting cells and are an important part of the immune system. Small numbers are present in normal skin, but numbers are increased in some inflammatory skin diseases, such as contact dermatitis. There are two types of allergic reaction in the skin: immediate reactions causing contact urticaria (hay fever is an immediate allergic reaction of the nasal mucosa), and delayed allergic reactions. This manifests as allergic contact dermatitis such as reactions from prolonged contact of nickel-containing metals with the skin. Merkel cells are difficult to visualize in routine histological sections but can be identified with special stains. Their precise function is not clear but they are thought to play a role in touch sensation. They can give rise to Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare aggressive malignant tumour most often seen in the elderly.

The dermis lies beneath the epidermis and is essentially fibrous connective tissue. The papillary dermis is a thin superficial layer containing fine collagen and elastic fibres, capillaries, and anchoring fibrils which help attach the epidermis to the dermis. The bulk of the dermis is formed by the reticular dermis which is mainly composed of thick collagen fibres and thinner elastic fibres. The collagen fibres provide much of the substance and tensile strength of the dermis, whilst elastic fibres provide the skin with elasticity. Small numbers of lymphocytes, macrophages, mast cells, and fibroblasts are present in the dermis together with blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, nerves, pressure receptors, and the skin appendages. The junction between the epidermis and dermis is not flat but has a complex three dimensional arrangement of downgrowths from the epidermis (rete ridges) and upgrowths from the papillary dermis (dermal papillae). This arrangement increases the surface area of the dermo-epidermal junction and enhances adhesion between the two layers.

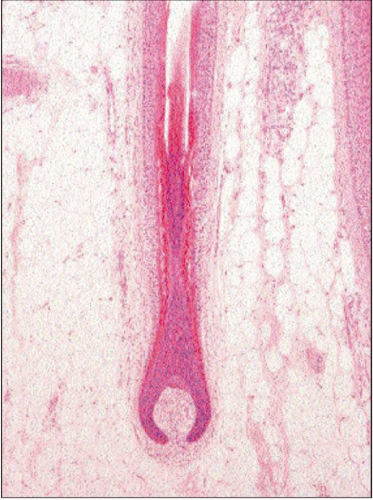

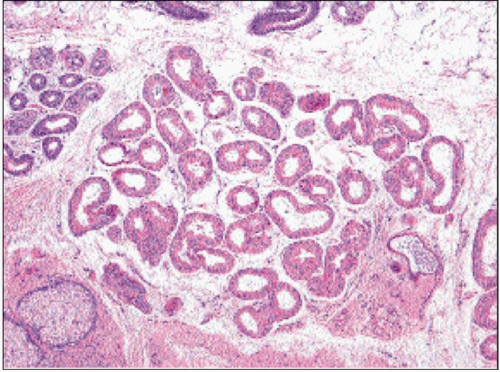

The skin appendages comprise the hair follicles with their attached sebaceous glands, the eccrine sweat glands and the apocrine glands (1.4, 1.5, 1.6 and 1.7). Hair follicles are widely distributed but are not present on the palms and soles. They

vary considerably in size from the large follicles of the scalp and male beard area to the more widespread small vellus follicles, present on the female face for example. The hair follicle is a tubular epithelial structure, which opens onto the skin surface and is responsible for producing hairs. The deepest part of the follicle, the hair bulb, is situated in the dermis or subcutaneous fat. The germinal matrix of the bulb consists of actively dividing cells that give rise to the hair shaft and inner root sheath. Keratinization of the epithelial cells occurs without keratohyalin and with no granular layer; this produces ‘hard’ keratin as opposed to the ‘soft’ keratin of the epidermis, which is produced with keratohyalin. The outer root sheath of the follicle is derived from a downgrowth of the epidermis. Melanocytes in the hair bulb produce melanin pigment, which is incorporated into the hair shaft and is responsible for hair colouration.

vary considerably in size from the large follicles of the scalp and male beard area to the more widespread small vellus follicles, present on the female face for example. The hair follicle is a tubular epithelial structure, which opens onto the skin surface and is responsible for producing hairs. The deepest part of the follicle, the hair bulb, is situated in the dermis or subcutaneous fat. The germinal matrix of the bulb consists of actively dividing cells that give rise to the hair shaft and inner root sheath. Keratinization of the epithelial cells occurs without keratohyalin and with no granular layer; this produces ‘hard’ keratin as opposed to the ‘soft’ keratin of the epidermis, which is produced with keratohyalin. The outer root sheath of the follicle is derived from a downgrowth of the epidermis. Melanocytes in the hair bulb produce melanin pigment, which is incorporated into the hair shaft and is responsible for hair colouration.

Hair follicle growth is cyclical with an active growth phase (anagen phase), which is followed by an involutional phase (catagen), and a resting phase (telogen) during which time hairs are shed. The anagen phase (during which time hairs are growing) lasts for at least 3 years, catagen lasts for approximately 3 weeks, and telogen 3 months. At any one time the majority of hair follicles (>80%) are in anagen phase, 1-2% are in catagen, and the remainder are in telogen phase.

Sebaceous glands are normally associated with and attached to a hair follicle (1.4). They are widespread but are particularly large and numerous on the central face and are absent from the palms and soles. Sebaceous glands are largely inactive before puberty but subsequently enlarge and become secretory. The glands are composed of lobules of epithelial cells, the majority of which contain abundant lipid within the cytoplasm and appear clear on histological sections. The lipid-rich secretion, sebum, is formed through necrosis of the epithelial cells and is secreted into the upper portion of the hair follicle. The function of sebum may include waterproofing and protection of the hair shaft and epidermis as well as inhibition of infection. The other main component of the hair follicle is the arrector pili muscle. This is a small bundle of smooth muscle situated in the dermis but attached to the follicle. Contraction of the muscle makes the hair more perpendicular.

Eccrine sweat glands are responsible for the production of sweat and play an important role in temperature control. They are widely distributed and are particularly numerous on the palms and soles, the axillae, and the forehead. The secretory glandular component is situated in deep reticular dermis (1.6). The gland is composed of a tubular coil of secretory epithelial cells with an outer layer of contractile myoepithelial cells. Sweat is transported via a duct, which spirals upwards through the dermis to open onto the skin surface. Glandular secretion and sweating are controlled by the autonomic nervous system.

Apocrine glands are histologically similar to eccrine sweat glands but are slightly larger (1.7). They are much less widespread and are principally located in the axillae and ano-genital region. Their precise function in man is unclear, though in some other mammals they have an important role in scent production.

History taking

History taking is the first part of a skin consultation. This is no different to any other medical specialty: one seeks to know when the condition started, which part of the body is affected, and how the condition has progressed since presentation. Clues to the diagnosis may come from asking the patient’s profession, if other family members or personal contacts are affected, and whether there has been exposure to allergens or irritants. Particular attention should be afforded to any treatments, both topical or systemic, that have been tried previously and if these have changed the character of the condition. In the past medical history, one considers whether the skin condition is a dermatological manifestation of a systemic disease, if there is a history of atopy (asthma, eczema, or hayfever), and also if the patient has suffered from previous skin complaints. Related to this, it is important to ask about family history of skin disease. Medications themselves can provoke skin eruptions and so a thorough drug history will include current and recent medications as well as any over-the-counter medicines or supplements. Often overlooked is the psychological impact of the skin condition. Changes in the patient’s quality of life may be a major factor in the patient consulting the physician in the first place. Through questioning a patient about how the condition affects the patient’s life, the physician will be able to assess what in particular is worrying the patient and explore the expectations for the consultation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree