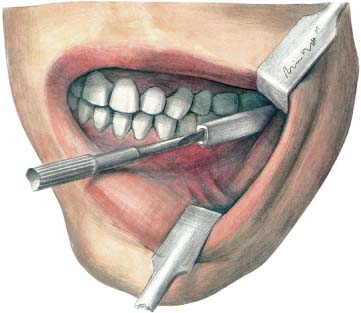

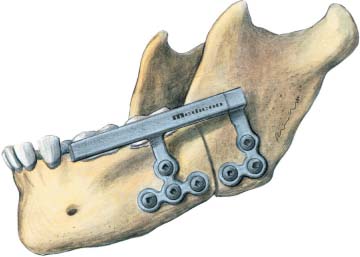

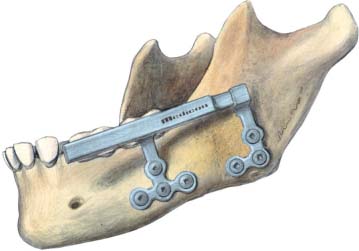

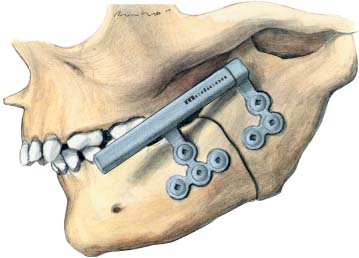

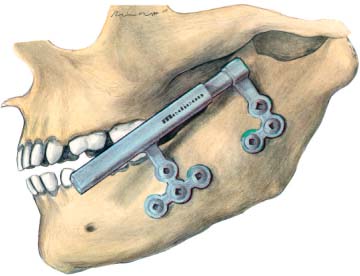

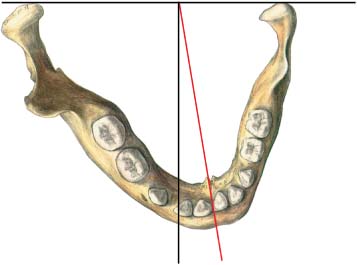

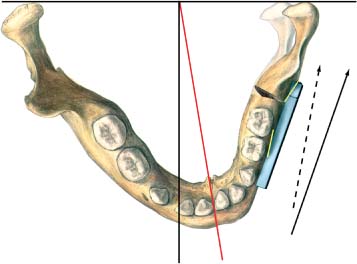

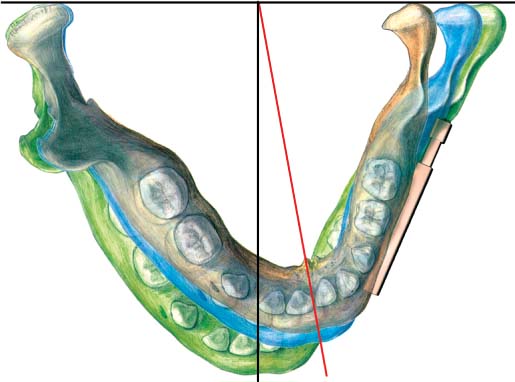

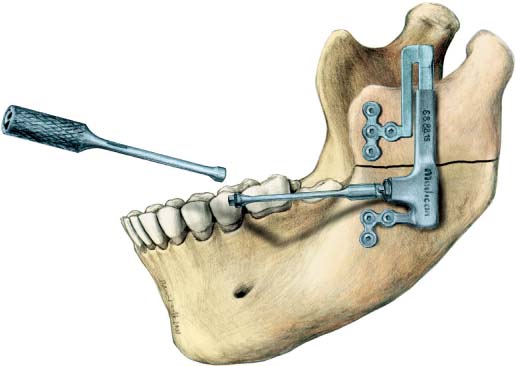

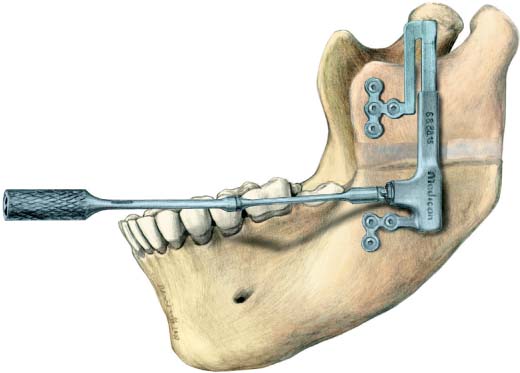

35 Intraoral Distraction Osteogenesis of the Mandible and the Maxilla The principle of distraction of the upper and lower extremities was developed by Ilizarov (1988) in the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics between 1950 and 1985. In the late 1980s miniaturized distractors were manufactured in Western Europe for use in hand surgery. Ilizarov and McCarthy exchanged ideas during a visit to New York, resulting in the first-ever distraction of malformed mandibles using transbuccally fixated hand-surgery distractors. McCarthy’s publication in 1992 sparked off an extensive search for distraction indications and frantic development of a variety of distractors for use in the craniofacial area of the skull. As well as multidimensionally adjustable equipment for extraoral use, more comfortable, enorally applied distractors were also developed, and these are used today in distraction of all parts of the craniofacial skeleton. Publications on enoral mandibular distraction first appeared in the mid-1990s (Wangerin and Gropp, 1994; Diner et al., 1996). In 1995 Cohen and coworkers first treated a severe craniofacial microsomia by simultaneous distraction of the maxilla, the orbita, and the mandible using two distractors. Chin and Toth (1996) distracted the maxilla first, shortening the activation pin which perforated the cheek as soon as possible after rapid maxilla advancement, thus avoiding scarring. Chin (1999) developed the equipment further to enable hidden Le Fort III distraction. Enoral distraction methods do not restrict the quality of life, they avoid scar formation in the cheek areas, they have the advantage of being invisible during use, they are easy to use (Fig. 35.1), and can be retained for unlimited periods. The sole existing disadvantage, the unidirectional distraction, was offset by Triaca et al. (1998) who developed multiaxial mandibular distractors. Enoral distraction in the craniofacial skeleton has now become a gold standard. Fig. 35.1 Demonstration of a horizontal mandibular distractor, activated by turning the screwdriver anticlockwise. Indications for distraction are all syndromes with mandibular malformation. A major symptom is airway obstruction in severe cases of mandibular retrognathia. Deglutition problems may also be caused by malformation of the mandible. Another indication is speech impairment due to a reduced oral cavity size (Wangerin, 2005). The development of distraction first broke the unspoken law that osteotomies should not be performed before bone growth is complete. Enoral distraction is possible even in small children from the age of 3–4 years. Prerequisite is a sufficient thickness of cortical bone surrounding the mandibular body, necessary to fix the distractor miniscrews. Acquired shortening of the mandibular body, ascending mandibular ramus, and condylar process can also be considered indications for distraction. These alterations may be caused by trauma or rheumatoid degeneration of the condyle; they may also be the result of bone infections or tumor resection. They occur mainly in adults, and distraction therapy is especially effective in the ascending ramus. In the past the only solution was to reconstruct the ramus–temporomandibular-joint unit by means of costochondral graft, a procedure that was not always successful, showing acceptable results in only one-third of cases. Distraction is less complicated, more comfortable for the patient and has a very high success rate. Prerequisite for a successful treatment is the postoperative integration of an interocclusal acrylic splint for 6 months to retain the resulting open bite until the ossification is complete. Fig. 35.2 Horizontal mandibular distractor in neutral position fixed to the mandible buccally parallel to the occlusal plane with monocortical 5 mm or 7 mm miniscrews. Fig. 35.3 Situation after horizontal distraction of the mandibular body to compensate for mandibular bony deficit. Fig. 35.4 Horizontal mandibular distractor situated at an angle to the occlusal plane to lengthen the mandibular body and the ascending ramus. Fig. 35.5 Oblique distraction: the result is an enlarged mandible with an open bite. A mandibular body which is simply too short is rare. It can occur unilaterally or bilaterally, in most cases in conjunction with a deficit of the ascending mandibular ramus. To reduce symptoms such as obstruction of the respiratory tract, difficult ingestion, or speech impairment, in some cases it is necessary to initially lengthen the mandibular body. This is often a prerequisite for a later, second distraction to elongate the likewise shortened ascending mandibular ramus. Under general anesthesia or local analgesia, a posterior buccal vestibular mucoperiosteal incision is made, followed by subperiosteal exposure limited only to the buccal surface of mandibular angle region, while preserving the periosteal attachment to lingual surface. A horizontal mandibular distractor 20 mm or 25 mm in length is inserted and fixed monocortically onto both sides of the planned osteotomy by means of one miniscrew per side, thus defining the direction of distraction. In most cases distraction runs parallel to the occlusal plane (Figs. 35.2, 35.3), less commonly obliquely, so that the distraction resultsin anopenbite (Figs. 35.4, 35.5). In cases of severe unilateral hemifacial microsomia it may at times be necessary to pre-bend the distractor miniplates to change distraction direction (Figs. 35.6–35.9) and to alleviate facial asymmetry. In such cases all the drill holes are bored in advance and the osteotomy is then marked with the Lindemann burr. The distractor is removed and the osteotomy performed. Fig. 35.6 Pre-bent miniplates on a horizontal mandibular dis-tractor used to laterally shift a rudimentary condylar process, which extends into the oral cavity. Fig. 35.7 Rudimentary shorter left ascending mandibular ramus with a noticeable midline shift to the left. Fig. 35.8 After retromolar diagonal mandibular osteotomy. Fixation of the distractor with pre-bent miniplates and resulting lateral shift of the shortened left condylar process. The original distraction direction has changed (unbroken arrow). Fig. 35.9 Distraction results in expansion of the mandible on the left side and positioning of the mandibular midline in the correct midline position. Fig. 35.10 Congenital malformations of the mandible often show a deficit in the ascending mandibular ramus; the most common distraction is therefore extension of the ascending ramus. The vertical mandibular dis-tractor is fixed to the buccal side. The distraction cylinder marks the direction of distraction. This must be carefully planned in each individual case. The distraction is rerouted by means of a gear mechanism, so that the activation rod (which is jointed to make it flexible) comes easily to rest in the floor of the mouth. Fig. 35.11 Distraction has lengthened the ascending ramus. If the osteotomy is situated in the area of cancellous bone, bone growth is unlimited. A lateral open bite results in the nonoccusal area, which will have to be supported by an interocclusal splint for 6months. It is important to expose the inferior alveolar nerve and completely split the mandible. This split should be checked, especially toward the medial periosteally covered mandibular surface. During the active bone growth period there is always a risk of just a greenstick fracture occurring. The distractor is then reinserted and fixed permanently onto both sides of the osteotomy with mono-cortical screws of 5 mm or 7 mm in length. A test distraction should be performed, so that any unforeseen problems can be dealt with. Ultimately, the incision is closed with resorbable sutures. If the mandibular body islong enough, many cases with a deficiency of the ramus require vertical distraction. In our patients this is the type of distraction we performed most often during the last decade (Kuder, 2006) (Figs. 35.10, 35.11). In these cases planning the distraction vector is a prerequisite for successful treatment. Based on cephalometric analysis of the lateral X-ray the vector can be defined and transferred during the operation. In individual cases we checked the distractor position intraoperatively by vector determination pins or by radiographic verification. In other severe cases of hemifacial microsomia, operation planning was performed with the aid of computed tomography (CT) and stereolithography and the complete surgical procedure was simulated on a model skull. During this procedure the fixation plates of the distractor were pre-shaped, ensuring high accuracy when intraoperatively positioning the equipment. The operative approach is identical to that in the horizontal mandibular area. Distraction is easily performed by patients themselves: with the aid of a mirror the patient uses a screwdriver to turn the activation pin in the mandibular vestibule. It can be pulled out at the end of distraction for total submergence of the device and to avoid infection in the distraction area (Fig. 35.12). The close connection between horizontal and vertical distraction in the mandible has already been described in the sections on body deficiency and ramus deficiency. Depending on primary presentation and the extent of the bony defect, procedures are planned individually for each patient. In the majority of cases horizontal distraction is performed first to relieve primary symptoms, which can be done by the age of 3 or 4 years according to the severity of the respiratory obstruction. In the early teenage years, vertical distraction is performed to develop a bony mandibular angle. In a case of a severe bilateral facial cleft with extreme mandibular retrognathy we performed two horizontal distractions 1 year apart, concluding therapy with a bimaxillary osteotomy at the end of skeletal maturity. Facial asymmetries caused by unilateral hemifacial micro-somia in combination with mandibular retrognathia were treated with a combination of horizontal and oblique mandibular distraction, and ultimately corrected by bimaxillary osteotomy (Wangerin et al., 2006).

Introduction

Mandibular Distraction in Congenital Malformation or Acquired Deficiency

Body Deficiency

Indication

Surgical Technique

Ramus Deficiency

Indication

Combinations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree