6

Injectable Fillers

New insights into the facial aging process—subcutaneous tissue loss and osseoerosion—and the evolution of safer, longer-lasting, and more convenient, readily available materials for adding volume to facial structures have added a new dimension to noninvasive facial rejuvenation. The ease of performance, lack of downtime, and infrequency of complications have increased the popularity and patient acceptance of these procedures. Now alternatives to bovine collagen are readily available. These techniques fit in well with the menu of combination therapies—neuromodulation, nonablative and ablative lasers, intense pulsed light (IPL), and light-emitting diode (LED) therapies.

There have been many discussions theorizing the attributes of the perfect filling agent. The distillate is simple. We want a product that can be administered safely, conveniently, rapidly, and painlessly and without leaving any traces that it has been injected. We want a product that does not result in any complications and that lasts a long time (forever would be preferable if we didn’t have to sacrifice safety for longevity). The ideal substance should be “biocompatible, nonimmunogenic, nonresorbable, nonpyogenic, noncarcinogenic, inexpensive, and nonmigratory, with the ability to be stored, shaped, removed, and sterilized easily.”1 We have not achieved filler nirvana, but the nonanimal-derived, stabilized hyaluronic acid products are the current state of the art, fulfilling much of our desired criteria.

Hyaluronic acid is a versatile macromolecule. It is a polysaccharide first isolated from bovine vitreous in 1934. It has been found in all tissues and in all vertebrates. It is a universal component of the extracellular space, where the molecule has multiple properties to constitute a matrix that supports the normal function of cells and tissues.2 Non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) is patented and produced by Q-Med AB, Uppsala, Sweden. We have used these products extensively since 1996 as an adjunct to our facial rejuvenation surgical procedures and as a stand-alone technique for adding volume to facial structures and for ablating rhytids.3–7 Others have had similar experience with this product.8–11 Hyaluronic acid derived from rooster combs (Biomatrix, San Tropez, France) has been used for almost 3 decades by ophthalmic surgeons during intraocular procedures. One of the authors (S.B.) participated in its early development to enhance and replace volume in the reconstructive and cosmetic arenas,12,13 (unpublished Hylan B [Biomatrix] monkey studies in 1990–1995). Both of these products can be used without prior skin testing.

For the last 2 decades, the most widely available and widely used substance for filling in facial rhytids has been bovine collagen.14 Collagen is a major structural protein in vertebrates, including humans. Approximately 25% of the protein in the human body and 75% in the skin is collagen. Injectable bovine collagen has been used extensively for facial rejuvenation since the 1980s.15–21 It requires skin testing before it can be used as filler. The second generation, derived from human fibroblast cell culture, can be used without prior skin testing.22 We will discuss this in greater detail later in this chapter.

The use of autogenous fat as a filling agent is somewhat more complicated. It has the advantages of potential permanence after implantation and unlimited volume available for implantation. But this technique has the disadvantage of requiring an additional procedure for harvesting and a degree of unpredictability after implantation. This discussion will be continued in Chapter 7.

The search for permanent synthetic fillers has been fraught with controversy. Materials that appear to give satisfying results in the short term may ultimately lead to complications after several years. With the exception of the silicone microdroplet technique, which can be useful when used in small quantities,23 at this time we do not use filling agents that claim to be permanent. The dictum that permanent filler may give rise to a permanent problem seems reasonable. The theory that the use of permanent filler is acceptable if it can be removed easily if the need arises is also not realistic in most cases. Solid materials that are implanted surgically do, however, fall into this category, and are discussed with regard to midface lifting and cheek augmentation in Chapters 11 and 12. We do not use solid implants in the lips.

Indications

Indications

Static Rhytids

Wrinkles, grooves, crevices, furrows, and fine lines that are the result of aging, sun exposure, and loss of skin and muscle turgor and elasticity can be filled, creating a smoother cutaneous surface and an illusion of a more youthful face. Facial animation (squinting, smoking) and a variety of facial expressions (smiling, frowning, crying, surprise) accentuate the static rhytids and will have to be treated concurrently.

Although theoretically any facial area can be filled, some areas typically require filling and other areas can only be partially filled or are filled with difficulty. We will discuss the filling of facial rhytids starting with the most cephalad areas, from the hairline, and work caudally, to the neck.

Tranverse forehead creases respond well to neuromodulation and usually do not require filling, except in cases of scarring and atrophic indentations following cutaneous steroid injections (Fig. 6-1A,B). Within the 1 cm “no Botox” zone above the eyebrows, however, rhytid filling works well to supplement neuromodulation of the forehead.

The glabellar area is managed well with neuromodulation when the vertical furrows are apparent only during frowning. However, static furrows that persistent at rest will require combined filling and neuromodulation, which are effectively and efficiently performed during one session (Fig. 6-2A,B). The depressions are filled and then the appropriate neuromodulating injections to the corrugator muscle insertions are given. In this manner the area can be filled most accurately. It is apparent that this combined therapeutic approach yields more complete and longer-lasting results than when either modality is used alone. The transverse crease over the bridge of the nose that is not completely effaced after neuromodulation of the procerus muscle can be filled in with satisfying results (Fig. 6-3A,B).

Vertical creases in the lateral aspect of the upper eyelid are sometimes visible after neuromodulation of the crow’s feet and lateral canthal areas. In patients with upper eyelid redundant folds, upper lid laser-assisted blepharoplasty and laser resurfacing constitute the most effective treatment. But for patients who are not emotionally or financially ready for this procedure, filling agents can work remarkably well as a temporizing maneuver.

Figure 6-1 (A) Acutaneous depression of the forehead followed Triamcinalone injections of a forehead scar. (B) Restylane was used to fill in cutaneous atrophic depressions following triamcinolone injections to reduce a scar.

Figure 6-2 (A), Deep glabellar furrows evident at rest require more than neuromadulation alone for complete correction. (B) These deep glabellar furrows were filled with Restylane layered on Perlane and concomittantly treated with Botox neuromodulation (40 units).

Figure 6-3 (A,B) After Botox neuromodulation of the patient’s corrugator and procerus muscles (60 units of Botox), her residual furrows and the bridge of her nose were recontoured with Perlane.

We do not recommend filling of crow’s feet creases or even deeper furrows in the lateral canthal area as a primary treatment. The skin is too fine and the muscle activity too rapid and repetitive. This area is much more efficiently managed with neuromodulation.

Meticulously applied, understated filling can be utilized for subtle lower eyelid contour irregularities. In thicker-skinned individuals with less translucent skin, tear trough deformities and hollowed, oversculpted lower lid contours can be filled in. When correcting tear trough deformities, the filling agent should be applied in the suborbicularis, supraperiosteal space. Even a pretarsal orbicularis muscle ridge can be re-created when desired.

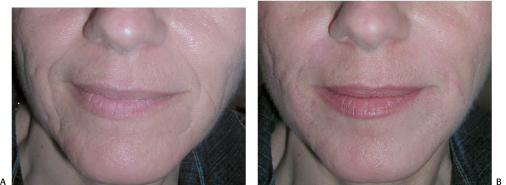

Nasolabial grooves are prime regions for filling to camouflage midfacial laxity. A combination of layered thicker and thinner materials can be used for an enhanced effect (Figs. 6-4A,B; 6-5A,B). The end results can be further accentuated with noninvasive skin tightening procedures utilizing radiofrequency or laser energy. Even following surgical midface lifting or nonsurgical tightening procedures, the application of filling agents to the nasolabial grooves may be necessary for the final effect.

Melomental grooves have been called by the unflattering name of marionette lines, or more clinically, oral commissures. These multicontoured facial cutaneous depressions can be ameliorated with filling agents, but more complete correction can be attained with concomitant neuromodulation of the depressor oris angulii muscles (the “dolphin shot”) and midface tightening procedures when necessary (see Chapters 14–16). Using a layered technique of thicker more deeply injected fillers and more superficially injected thinner fillers is helpful. This combination technique can also be used to support the corners of the mouth.

Figure 6-4 (A,B) Nasolabial folds were diminished with Restylane layered on Perlane.

Lips can be augmented and recontoured effectively with a combination of hyaluronic acid products of different viscosities, (see Chapter 14). The upper lip border can be accentuated and vertical rhytids softened with less viscous materials (Fig. 6-6A,B), whereas the body of the lip is more efficiently filled with more viscous products (Fig. 6-7A,B).

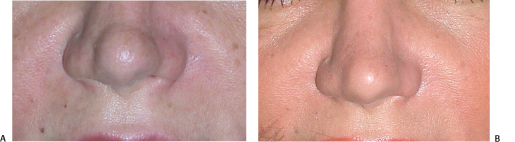

Recontouring of the facial bony contours (cheek bones, chin, jawline, nasal deformities) can be achieved with thicker fillers injected in a supraperiosteal plane (Fig. 6-8A,B). This can give a satisfying result and can also have a temporizing effect so patients can see if they like their new facial contour before they have a definitive surgical procedure.

Soft tissue defects can be improved utilizing a variety of agents. Small, distensible traumatic and acne scars can be filled over time with multiple sessions, using hyaluronic acid gel or silicone (Fig. 6-9A,B). Broad, ill-defined areas of scarring or atrophy will require thicker material that is available in larger quantities-fat, polylactic acid. Ice-pick scars are difficult to fill and are better managed with a biopsy punch, suturing, and nonablative laser collagen stimulation or 50% TCA focally applied with a tooth pick into the scar.

Figure 6-5 (A,B) Perlane was used to soften this animated patient’s nasolabial folds.

Figure 6-6 (A) This patient desired treatment of her upper lip rhytids and augmentation of her lips and chin. (B) The perioral area has been rejuvenated with Botox neuromodulation of the depressor anguli oris muscles, Cosmoplast and Restylane to accentuate the upper lip border, and Perlane to fill the body of the lip, to support the corners of the mouth, soften the oral commissures, and augment the chin.

Figure 6-7 (A,B) Perlane was used to create visible upper and lower lips.

Figure 6-8 (A,B) Perlane was used to correct these nasal deformities while the patient was contemplating corrective surgery.

Figure 6-9 (A,B) Restylane layered on Perlane made a significant improvement in the correction of this patient’s acne scarring.

Choice of Materials

Choice of Materials

Permanent Filling Agents

Injectable filling materials can be classified as either permanent or temporary. As already stated, we do not in general use permanent filling agents. Silicone is a permanent filler. Fat is potentially permanent, but its duration after implantation can be unpredictable. Fat implantation is discussed in detail in Chapter 7.

Silicone in its liquid injectable form has been used since the 1940s. However, it has been misused during the subsequent decades. Excessive volumes and adulterated forms have been injected, causing subsequent complications and controversy. Two U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medical-grade liquid injectable silicones are available today. Adatosil (Escalon Medical Corp., Chicago, Illinois) and Silikon (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, Texas) are approved for the tamponade of retinal detachments. The FDA’s Modernization Act (1997) allows for their off-label use for soft tissue augmentation.23

Silicone is inert and lighter than water and human tissue. Following microdroplet liquid silicone injection, there is a transient, mild inflammatory response for about the first 2 weeks, followed by a fibroblastic response beginning at 1 month and accompanied by collagen deposition.24 Eleven to 14 months after implantation there is intense fibrosis. This may cause some hardening of the tissues injected, and thus silicone is best injected into areas of denser, less mobile tissue.

Temporary Filling Agents

Hyaluronic Acid and Hyaluron

Although hyaluronic acid is found in the highest concentrations in connective tissues, 56% is found in human skin. Because it is a uniform, unbranched linear polysaccharide, hyaluronic acid has a simple chemical structure that is identical in all species and tissues (only the length of the molecular chain varies), and it can be considered an ideal biomaterial.2 It is composed of hydrophilic disaccharide units containing glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine. Pure hyaluronic acid is inherently biocompatible. It is the impurities in the hyaluronic acid raw material, especially of animal origin, that can affect biocompatibility. The following products produce longer lasting results and fewer hypersensitivity reactions than collagen products.10 No pretreatment skin testing is required.

Restylane (Q-Med, Uppsala, Sweden), FDA approved December 12, 2002, has 20 mg/mL of hyaluronic acid with a gel bead size of 250 μm and 100,000 units per mL. It has 0.5 to 1% cross linking.

Hylaform (INAMED, Santa Barbara, California), FDA approved April 2004, has 5.5 mg/mL of hyaluronic acid and 20% cross linking.

Perlane (Q-Med, Uppsala, Sweden), not approved in the United States, has 20 mg/mL of hyaluronic acid with a gel bead size of 1000 μm and 10,000 units per mL and less than 1% cross linking.

Hylaform Plus (INAMID, Santa Barbara, California), FDA approved October 13, 2004, has 5.5 mg/mL of hyaluronic acid, and has a larger gel particle size and is more viscous than hyaluronic acid. It has 20% cross linking.

Restylane Touch

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree