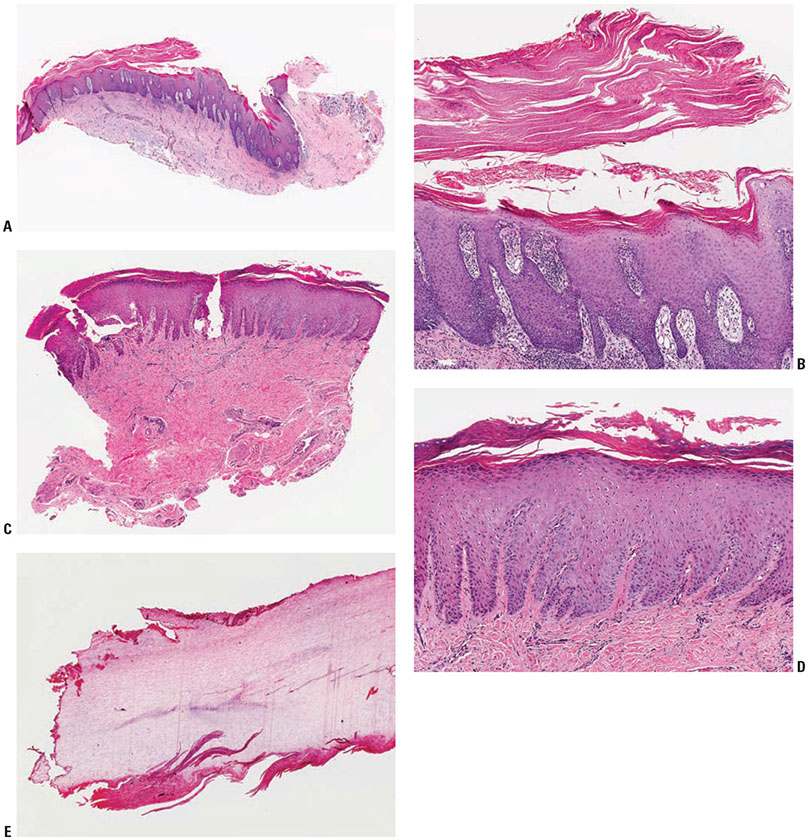

Figure 19-1 Nail unit psoriasis. A: Onycholysis and the oil drop sign are seen in the distal nail plate. B: Onycholysis seen on the great toenail in a patient with nail unit psoriasis. The nail bed biopsy from this nail is seen in Fig. 19-2C–E. C: Typical features of nail unit psoriasis are seen in this image. There is onycholysis associated with an erythematous rim at the periphery of some of the nails, splinter hemorrhages, and a few pits.

Histopathology. Sections should be stained with hematoxylin and eosin and also with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain or silver methenamine stain to rule out fungal infection. Because psoriasis and onychomycosis share many clinical and histologic features, a positive fungal staining is the only reliable way of distinguishing histologically between psoriasis and onychomycosis. It is important to remember that a patient with nail unit psoriasis may also develop onychomycosis. Treatment of the onychomycosis may unmask the underlying nail unit psoriasis.

The nail plate can show foci of parakeratosis on the surface of it, which, when shed, leave pits on the plate. With psoriatic leukonychia, foci of parakeratosis are located in the deeper portions of the plate.

The oil drop sign is histologically characterized by hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, with collections of neutrophils in the stratum corneum representing a Munro microabscess and spongiform pustules in the granular layer. The nail unit epithelium may show hypergranulosis, with focal hypogranulosis. There is elongation of the dermal papillae with dilatation and proliferation of capillaries surrounded by lymphocytes, histiocytes, and occasional neutrophils.

Distal nail onycholysis shows a similar histology and therefore has a similar histogenesis. The split in psoriatic onycholysis occurs between where neutrophils and parakeratotic foci are located within the plate and the underlying hyponychium. The yellow leading edge of onycholytic nail correlates with the presence of neutrophils in the nail plate keratin.

The changes of well-developed nail unit psoriasis of the distal nail unit with subungual hyperkeratosis will show the nail bed epithelium with psoriasiform acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, and capillary proliferation. Neutrophils may be present in the superficial epidermis and within the keratin.

Late or chronically traumatized psoriatic nails may develop features of lichen simplex chronicus, including marked compact orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, and fibrosis of the papillary dermis, characterized by vertical streaks of coarse collagen fibers. Histologic features of nail unit psoriasis are presented in Fig. 19-2.

Figure 19-2 Nail unit psoriasis. A: This longitudinal excisional specimen includes the cul de sac, matrix epithelium, and part of the nail bed epithelium. Psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia is seen. B: This medium-power view of the matrix epithelium shows epithelial hyperplasia, hypogranulosis, and neutrophils within areas of overlying parakeratosis. C: This punch biopsy of the nail bed shows features that can be seen in nail unit psoriasis affecting that anatomic area of the nail unit. There is psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and papillomatosis. Tortuous vessels are seen in the papillary dermis. D: Medium-power view of this same specimen described in C. E: The nail plate that was overlying the nail bed specimen seen in C. Note the neutrophils in an area of parakeratosis at the ventral aspect of the nail plate. The nail that was biopsied is seen in Fig. 19-1B.

Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of nail unit psoriasis is the same as that of psoriasis affecting other areas of the skin. For a complete discussion, see Chapter 7.

Differential Diagnosis. The main clinical differential diagnosis of nail unit psoriasis is onychomycosis, given the common overlapping clinical features of nail plate thickening, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis. A nail clipping sent for histology is an efficient way to distinguish between these two entities. It is important that the nail clipping be performed from as proximal as possible from the free edge of the nail plate in order to obtain a sample with the highest likelihood of identifying the fungus. Nail plate changes seen with eczematous dermatitis affecting the nail unit can also mimic nail unit psoriasis occasionally.

Principles of Management. These are exciting times for the treatment of nail unit psoriasis. The selection of an appropriate therapy will depend on what anatomic areas of the nail unit are affected. Intralesional steroid works well for pitting, surface ridging, and thickening of the nail plate, as well as for subungual hyperkeratosis and onycholysis (14). Areas of onycholysis can have a good response to topical therapies such as topical retinoids, vitamin D analogs, anthralin, tacrolimus, and topical steroids (13–17). New information supporting the use of the 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of nail unit psoriasis is available (18). There are emerging data on the usefulness of topical indigo naturalis oil extract for nail unit psoriasis (19–21). Systemic therapies directed at treating cutaneous psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis will also improve the nails, including the new biologic medications cyclosporine, methotrexate, and acitretin (12–14,17,22). Even though all of these choices are possible, it is also important to remember that simple strategies of good nail care will also help control and alleviate nail unit psoriasis. These maneuvers include good nail protection and keeping the nails short to avoid a Koebner phenomenon with a long nail plate acting as a lever and causing trauma at the nail plate–nail bed junction (14,17). All patients with nail psoriasis warrant an evaluation for psoriatic arthritis, which, if present, generally requires systemic therapy to manage.

NAIL UNIT LICHEN PLANUS

Clinical Summary. The incidence of nail involvement occurring in association with disseminated lichen planus ranges from 1% to 10%. A recent study of 316 pediatric patients with a mean age of 10.28 years affected by lichen planus found the nails to be affected in 13.9% (23). In this pediatric study, 90.9% of patients with nail unit lichen planus had lichen planus at other sites (23). Lichen planus may develop in the absence of cutaneous involvement and is most common in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Fingernails are more commonly affected than toenails. Lichen planus may involve the nail matrix, nail bed, hyponychium, and nail folds. Examination and understanding of the pathogenesis of clinical changes will aid the clinician in determining where to sample the nail unit.

Involvement of the proximal nail matrix results in onychorrhexis (longitudinal grooves and ridges of the nail plate) (Fig. 19-3). If nail unit lichen planus is treated early in its course, the changes may be reversible. However, as with other skin appendages, such as hair, if the process progresses, fibrosis and scarring may result, leading to permanent deformity. If there is scarring of the nail unit from lichen planus, anonychia (total loss of the nail plate) can result. A classic clinical feature of nail unit lichen planus is the development of a pterygium, which is caused by scarring and connection of the proximal nail fold to the nail bed. The resulting and remaining nail plate resembles angel’s wings.

Figure 19-3 A: Typical features of nail unit lichen planus. There is onychorrhexis (longitudinal striations of the nail plate) and atrophy of the distal nail bed. The black ink lines mark the sites for incisions to obtain the matrix biopsy, seen in Fig. 19-4. B: The nail matrix biopsy was obtained by reclining the proximal nail fold after incisions were made in it. The skin hook holds the reclined proximal nail fold away from the matrix biopsy site.

If the nail matrix is involved diffusely, onychoschizia (lamellar changes with fragility and brittleness) results. Matrix involvement by lichen planus can also present clinically as trachyonychia (rough nails), red lunulae, erythronychia, and atrophy of the nail unit (24). Occasionally, lichen planus of the nail bed alone may occur, and can manifest clinically as onycholysis. Papular lesions of lichen planus may occur in various locations of the nail bed and lead to focal atrophy. As a result, the overlying nail plate will be focally dimpled or spooned (koilonychia). Nail bed lichen planus lesions can also manifest clinically with hyperkeratosis (24). In some cases, complete shedding of the nail plate due to diffuse nail bed involvement may occur. Hyperpigmentation of the nail (melanonychia) may result with nail unit lichen planus.

A recent study demonstrated a potential link between metals found in dental materials and the course of nail unit lichen planus (25). Six out of 10 patch test-positive nail unit lichen planus patients improved with the removal of the metal-containing dental materials or discontinuation of systemic disodium cromoglycate. Causative metals in the dental materials were found in biopsies of the nail tissues.

Idiopathic atrophy of the nails is a form of nail lichen planus exclusively seen in children, and presents with diffuse and rapid destruction of the nails over a few months (26).

Lichen planus limited to the nail units, also known as isolated nail lichen planus (24), can be difficult to diagnose clinically, and in these cases a biopsy is extremely useful. Often, patients with this form of lichen planus have been treated with antifungal agents without success before being referred for evaluation. A large study of 67 cases of isolated nail lichen planus demonstrated an average age of 47, a male predominance (64%), and that the fingernails were involved in 94% of the cases and toenails were involved in 53.73% of the cases (24). Only 4 of the patients had isolated nail lichen planus of the toenails only. In this study, 120 biopsy specimens were taken, and in 90% of the specimens, pathologic features of lichen planus were identified, confirming the utility of nail unit biopsy to confirm the diagnosis (24).

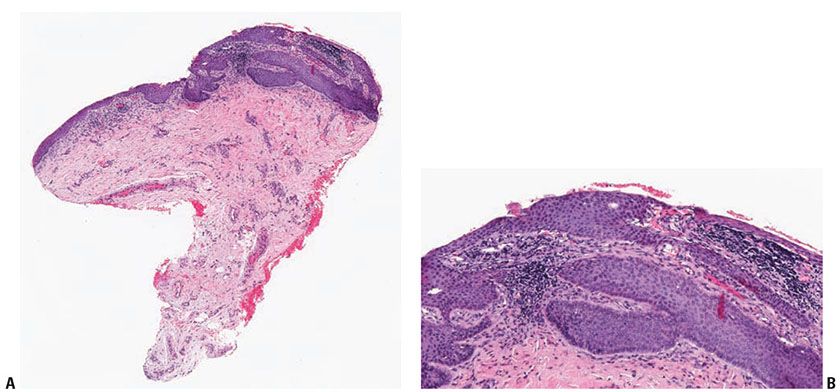

Histopathology. As in lichen planus of the skin, hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, vacuolar degeneration, necrotic keratinocytes, Civatte bodies, and a bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes at the dermal–epidermal junction accompanied by melanophages can be seen (Fig. 19-4). The hypergranulosis tends to be less wedge-shaped than in other parts of the skin. In our experience, the intensity of the inflammation in nail unit lichen planus is less than that seen in other areas of the skin. Accordingly, we have noticed that other histologic features typical of a lichenoid dermatitis are not as intense, such as the number of dyskeratotic keratinocytes and the degree of vacuolar degeneration. It is unusual, but the inflammation affecting the nail matrix may have a plasma cell predominance (27).

Figure 19-4 Biopsy of the nail matrix demonstrating features of nail unit lichen planus. A: Low-power view of this nail matrix punch biopsy shows a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate that abuts the epithelium. B: Medium-power view shows some vacuolar change at the basal layer of the epithelium. This specimen is taken from one of the nails seen in Fig. 19-3A. A part of the surgical procedure is seen in Fig. 19-3B.

Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of nail unit lichen planus is the same as that of lichen planus affecting other areas of the skin. For a complete discussion, see Chapter 7.

Differential Diagnosis. The clinical differential diagnosis for nail unit lichen planus includes other inflammatory dermatoses affecting the nail unit, such as eczematous dermatitis and psoriasis. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) affecting the nail unit should also be considered in the clinical differential diagnosis. In a study that included 14 patients with chronic cutaneous GVHD, longitudinal ridging was the most frequently observed nail change, and roughness of the nail plate was the second most frequently observed finding. Other overlapping clinical findings between nail unit GVHD and nail unit lichen planus that were noted in the study include fragility, pterygium formation, onychoatrophy, and onycholysis (28). Examination of the other areas of the skin surface can be helpful if typical lesions of other dermatoses are present. Making the diagnosis can be difficult if the changes are limited to the nails. The histopathologic features are distinct from other inflammatory dermatoses affecting the nail unit, when fully developed.

Principles of Management. Nail unit lichen planus can be difficult to treat. The therapeutic modality should be chosen based on what anatomic area of the nail unit is affected. For example, onychorrhexis is caused by inflammation affecting the matrix; so appropriately directed intralesional steroids to this area are helpful (29). Conversely, if onycholysis is present, topical steroids can be applied directly to the nail bed. Topical tacrolimus has also been reported to be effective (30). If many nails are affected, systemic steroids can be employed, and literature exists supporting both oral and intramuscular delivery routes (31). Case reports have demonstrated the effectiveness of the biologic medication etanercept, the oral retinoid alitretinoin, and the combination of the topical retinoid tazarotene and the topical steroid clobetasol for the treatment of nail unit lichen planus (32–34). Given the association between lichen planus and hepatitis C, patients with nail unit lichen planus may warrant evaluation for hepatitis C and should be referred to a hepatologist if evidence of infection is found.

INFECTION

Onychomycosis

Clinical Summary. Fungal infection of the nails is the most common nail disorder, accounting for up to 50% of nail disorders. Onychomycosis is present in 2% to 14% of the general population, rising to 50% in adults older than 70 years (35). A recent study in Brazil showed 28.3% of 7,852 patients examined were clinically diagnosed with onychomycosis (36). Medical conditions associated with an increased incidence of onychomycosis include diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, HIV infection, immunosuppression, obesity, smoking, a family history of onychomycosis, and increased age (37,38

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree