2 History of onabotulinumtoxinA therapeutic

Summary and Key Features

• Botulinum toxin has become a valuable therapy for treating selected neurological and urological disorders and managing the appearance of glabellar facial lines

• After identification of a muscle-relaxing substance present in sausages, scientists attributed these effects to a bacterium that became known as Clostridium botulinum. They isolated and characterized the neurotoxin, and described its mechanism of action on nerve terminals

• Dr Alan Scott, an ophthalmologist in San Francisco, began studying botulinum toxin type A (‘Oculinum’) in the 1960s and 1970s as a possible treatment for patients with strabismus

• Following Alan Scott’s successful studies in strabismus patients, he and others, including our group at Columbia University working under a research protocol, examined botulinum toxin type A in several neurological conditions, including blepharospasm, cervical dystonia, and also hyperfunctional facial lines, marked by the overactivity of facial or neck muscles

• Oculinum was approved for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm by the United Stated Food and Drug Administration in 1989

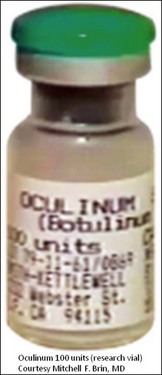

• Alan Scott’s first manufactured research therapeutic, Oculinum, was later acquired by Allergan and renamed Botox®

• Other botulinum toxin products have subsequently been licensed, each having its own clinical profile and dosing strategy; today these products have unique non-proprietary names

• As of 2011, onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox® / Botox® Cosmetic) is approved for multiple indications worldwide, including eight indications in the United States

• In providing a treatment option for several rare neurological conditions, the clinical development of onabotulinumtoxinA may have contributed to an enhanced understanding of these disorders

Identification, isolation, and characterization

The first well-described cases of medical illness after oral ingestion of an apparent foodstuff that may have contained some botulinum toxin were reported between 1817 and 1822 by the German physician Justinus Kerner. Kerner noted that the active substance interrupted signals from the motor nerves to muscles, but spared sensory nerves and cognitive abilities. He also theorized that the substance could possibly be used as therapy for medical conditions when ingested orally.

The bacterial etiology of botulism was first noted by the microbiologist Emile Pierre van Ermengen who documented his findings in 1897, identifying and naming the responsible bacteria as Bacillus botulinus, which later became Clostridium botulinum. In 1905, Tchitchikine found that C. botulinum produced a substance that affected neurotransmitter function. In 1919, Professor Burke of Stanford University described an alphabetical classification for the different serotypes of botulinum toxin based on his toxin–antitoxin experiments.

Exploration of clinical potential

Scott took the crystalline toxin into his laboratory and diluted it into small aliquots, buffered it with albumin instead of gelatin, and developed testing and storage conditions. He found that injecting minute amounts into extraocular muscles of monkeys with electromyographic (EMG) guidance produced long-lasting effects for the correction of strabismus and, at the doses used, without any systemic effects. Scott published these preclinical results in 1973, performed additional preclinical toxicology studies to evaluate doses that produced systemic effects in primates and obtained an Investigational New Drug (IND) designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to conduct the first clinical trial for humans with strabismus in 1977 by injecting minute amounts locally into the extraocular muscles. He called his formulation ‘Oculinum’ (Fig. 2.1). This clinical trial led to the 1980 publication of the first 19 patients, where efficacy in treating strabismus was reported.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree