1 Historical Milestones in Female Pelvic Surgery, Gynecology, and Female Urology

ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

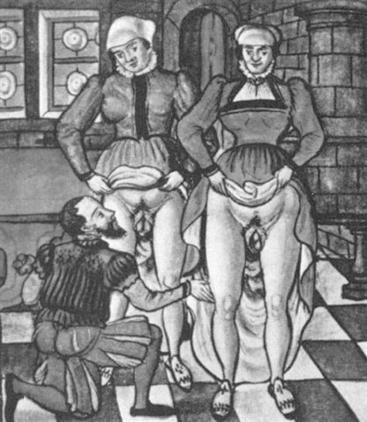

From the earliest days of recorded medical history, physicians struggled with the problems of pelvic organ prolapse (Fig. 1-1), urinary incontinence, and vesicovaginal fistula. An inadequate understanding of pelvic anatomy plagued practitioners before the nineteenth century. Ignorance of asepsis, the absence of anesthesia, faulty suture materials, inadequate instrumentation, and suboptimal exposure delayed any consistent success until the mid-nineteenth century.

Figure 1-1 Sixteenth-century woodcut showing examination of women with uterine prolapse.

(From Stromayr C. Die Handschrift des Schnitt-und Augenarzles Caspar Stromayr, Lindau Munscript, 1559.)

The evolution of pelvic surgery from the Hippocratic age to the antiseptic period is a fascinating one, where original theories occasionally fell from favor only to be resurrected and popularized by subsequent generations. Equally intriguing is the development of a wide array of innovative instrumentation and materials that often paralleled many surgical advances. This chapter is an attempt to touch upon the milestones that occurred along the way and to pay homage to the pioneers who helped shape a specialty and upon whose shoulders we stand. The author’s selection of important milestones in our specialty up to 1961 is shown in Table 1-1. Note that this chapter emphasizes American contributions and milestones that influenced contemporary thought, patient care, and surgical practices. I am grateful for the works of Dr. Thomas Baskett, Dr. James V. Ricci, and, particularly, Dr. Harold Speert, whose extensive research on the subject made this chapter possible.

Table 1-1 Timeline of Milestones Related to Pelvic Surgery and Female Urology

| Second half of first century AD Soranus’s (De Morbis Mulierum) first good description of the human uterus. | |

| 1561 | First accurate description of the human oviduct. Observationes Anatomicae by Gabriele Falloppio. |

| 1672 | First accurate account of the female reproductive organs and ovarian follicles (“Graafian Follicles”) De Mulierum Organis Generationi Inservientibus by Regnier de Graaf. |

| 1677 | Description of the vulvovaginal glands, “Bartholin Glands.” De Ovariis Mulierum by Caspar Bartholin. |

| 1691 | Description of the female inguinal canal. Adenographia by Anton Nuck. |

| 1705 | François Poupart describes the inguinal ligament and its function. |

| 1727 | Jacques Garengeot modifies a trivalve speculum to better differentiate “vaginal hernias” during pelvic examination. |

| 1737 | Description of the peritoneum and posterior cul-de-sac. A Description of the Peritoneum by James Douglas. |

| 1759 | Description of the embryonic mesonephros or “Wolffian Body and Duct.” Theoria Generationis by Caspar Fredrich Wolff. |

| 1774 | William Hunter completes his monumental work, Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus, which remains the finest work on uterine anatomy to date. |

| 1801 | Joseph Claude Récamier popularizes the use of a tubular vaginal speculum to treat ulcers and infections of the vagina and cervix. |

| 1803 | Pieter Camper describes the superficial layer of abdominal fascia. |

| 1804 | Astley Paston Cooper describes the ligamentous covering of the pubis and its condensation above the linea ileo-pectinea as it extends from the pubis outward. |

| 1805 | Philipp Bozzini introduces his lichtleiter (light conductor), the earliest endoscope. |

| 1809 | Ovariotomy is performed by Ephraim McDowell. |

| 1813 | Conrad Johann Martin Langenbeck carries out the first planned and successful vaginal hysterectomy. |

| 1825 | Marie Anne Victorie Boivin devises the bivalve vaginal speculum. |

| 1836 | Charles Pierre Denonvilliers describes the rectovesical fascia. |

| 1838 | John Peter Mettauer uses lead sutures to perform the first surgical correction of vesicovaginal fistula in the United States. |

| 1849 | Anders Adolf Retzius describes prevesical space. |

| 1852 | James Marion Sims describes his knee-chest positioning of patients for vesicovaginal fistula repair. |

| 1860 | Hugh Lenox Hodge details the use of his pessary to correct for uterine displacement. |

| 1877 | Léon Le Fort describes his method of partial colpocleisis as a simple and safe means for treatment of uterine prolapse. |

| 1877 | Max Nitze introduces an electrically illuminated cystoscope. |

| 1878 | T.W. Graves designs a speculum that combines features of both bivalve and Sims’s specula. |

| 1879 | Alfred Hegar introduces his metal cervical dilator to replace laminaria. |

| 1890 | Friedrich Trendelenburg describes his technique for positioning patients to facilitate a transvesical approach in the repair of vesicovaginal fistula. |

| 1893 | Howard Atwood Kelly devises the air cystoscope for inspection of the bladder and identification and catheterization of the ureters. |

| 1895 | Alwin Mackenrodt provides a comprehensive and accurate description of the pelvic connective tissue and correlation with pelvic prolapse. |

| 1898 | Ernst Wertheim performs radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. |

| 1899 | Thomas James Watkins performs an “interposition” operation for treatment of uterine prolapse associated with cystocele. Thus, the uterus is brought forth through an anterior colpotomy incision and sutured under the anterior vaginal wall, with the cervix secured posteriorly. The markedly anteverted uterus essentially pivots on twisted broad ligaments, thus producing antagonistic forces, because any dropping of the bladder increases the anterior displacement of the uterus, and any prolapse of the uterus elevates the cystocele. |

| 1900 | David Todd Gilliam describes his method of uterine ventrosuspension, whereby he ligated the proximal round ligament and attached it to the anterior rectus sheath lateral to the rectus muscle. |

| 1900 | Hermann Johannes Pfannenstiel introduces a transverse incision for laparotomy. |

| 1901 | Alfred Ernest Maylard advocates the oblique transection of the rectus muscles to improve exposure. |

| 1901 | John Clarence Webster and John Baldy introduce their suspension technique for correction of uterine retroversion, whereby the proximal round ligament is brought under an opening made under the utero-ovarian ligament and, ultimately, secured at just above the uterosacral ligament. |

| 1909 | George Reeves White noted that certain cases of cystocele were due to lateral paravaginal defects and thus could be repaired by reconnecting the vagina to the “white line” of the pelvic fascia. |

| 1910 | Max Montgomery Madlener introduces a popular female sterilization technique using ligation of the tube alone. |

| 1911 | Max Brödel becomes head of the world’s first Department of Medical Illustration at Johns Hopkins University. |

| 1912 | Alexis Victor Moschcowitz describes the passage of silk sutures around the cul-de-sac of Douglas to prevent prolapse of the rectum. |

| 1913 | Howard Atwood Kelly describes the Kelly plication stitch, a horizontal mattress stitch placed at the urethrovesical junction to plicate the pubocervical fascia and “reunite the sphincter muscle.” |

| 1914 | Wilhelm Latzko describes a technique for vaginal closure of vesicovaginal fistula following hysterectomy. |

| 1915 | Arnold Sturmdorf introduces his tracheloplasty technique. |

| 1917 | W. Stoeckel is the first to successfully combine a fascial sling and sphincter plication for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. |

| 1929 | Ralph Hayward Pomeroy devises a method of female sterilization involving ligation and resection of the tube. |

| 1940 | Noble Sproat Heaney describes his technique for vaginal hysterectomy using a clamp, needle holder, and retractor of his own design. His method for closing the vaginal cuff that incorporates peritoneum, vessels, and ligaments is known as the “Heaney stitch.” |

| 1941 | Leonid Sergius Cherney suggests a modified low transverse abdominal incision, whereby the rectus muscle is cut at its very insertion into the pubis to provide better access to the space of Retzius. |

| 1941 | Raoul Palmer popularizes the use of the laparoscope in gynecology. |

| 1942 | Albert H. Aldridge reports on rectus fascia transplantation as a sling for relief of stress urinary incontinence. |

| 1946 | Richard W. TeLinde continues the Johns Hopkins legacy in gynecology with the introduction of his text, Operative Gynecology. |

| 1948 | Arnold Henry Kegel describes his progressive resistance exercise to promote functional restoration of the pelvic floor and perineal muscles. |

| 1949 | Victor Marshall, with Marchetti and Krantz, describe retropubic vesicourethral suspension for stress urinary incontinence. |

| 1957 | Milton L. McCall describes his posterior culdoplasty to prevent or treat enterocele formation at vaginal hysterectomy. |

| 1961 | John Christopher Burch introduces his method of urethrovaginal fixation for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. |

GYNECOLOGY IN ANTIQUITY

Gynecology in antiquity finds its roots in the Ebers papyrus (1500 BC) that portrayed the uterus as a wandering animal— usually a tortoise, newt, or crocodile—capable of movement within its host. Hippocrates perpetuated this animalistic concept, stating that the uterus often went wild when deprived of male semen. He provided the earliest description of a pessary, using a pomegranate to reduce uterine prolapse and using catheters fashioned from tin and lead to irrigate and drain the uterus. The seven cells doctrine of the Common Era replaced the animalistic concept, depicting the uterine cavity as being divided into seven compartments whereby male embryos developed on the right, females on the left, and hermaphrodites in the center. Similar notions remained popular until the Middle Ages. Soranus of Ephesus (AD 98 to 138) is commonly considered the foremost gynecologic authority of antiquity. He described the uterus based on human dissection and performed a hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. His writings provided the foundation for gynecologic texts up to the seventeenth century. The ancients used instruments fashioned from tin, iron, steel, lead, copper, bronze, wood, and horn. Those made of iron and steel were likely quite popular, but very few survived the oxidation of more than two millennia. Gynecologic instruments from the first century BC were unearthed at Pompeii, including forceps, catheters, scalpels, as well as massive bivalve, trivalve, and quadrivalve vaginal specula.

THE RENAISSANCE

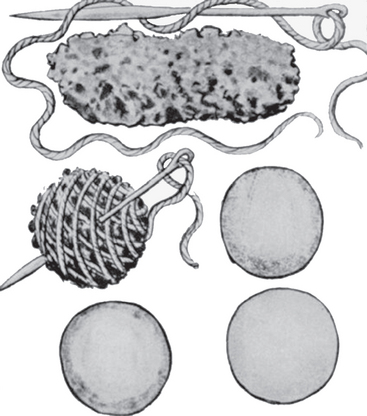

Among the more comprehensive accounts of sixteenth century gynecologic surgery is Caspar Stromayr’s Practica Copiosa, which contains beautifully executed watercolors depicting diseases of women. Included are illustrations of the examination of uterine prolapse and placement of a pessary comprised of sponge bound by twine, sealed with wax, and dipped in butter (Figs. 1-2 and 1-3). Despite the many advances regarding pelvic anatomy during the Renaissance, the approach to most gynecologic problems changed very little from that which was popular during the classical period.

Figure 1-2 Sixteenth-century woodcut depicting placement of a pessary to treat uterine prolapse.

(From Stromayr C. Die Handschrift des Schnitt-und Augenarzles Caspar Stromayr, Lindau Munscript, 1559.)