16

Hand and Forearm Tendon Injuries

Injuries of the distal upper extremity range from simple lacerations to complex open blast injuries involving destruction of vital soft tissue nerve and vascular structures. Effective evaluation and treatment requires detailed attention to the mechanism, time, and level of injury. The initial evaluation of an injured hand or forearm consists of a complete assessment for bony, vascular, and soft tissue injuries. Complex injuries mandate prioritizing reconstruction. First, the osseous structures are stabilized with internal or external fixation methods. Following rigid stabilization of the extremity, soft tissue repair is undertaken to protect and provide minimal tension over delicate vascular and nerve reconstructions. When loss of soft tissue is extensive, priority is placed on bony stabilization and revascularization. Soft tissue coverage is then employed and the soft tissue is allowed to stabilize and heal for 3 weeks. Tendon and nerve reconstruction is delayed until soft tissue coverage has stabilized.

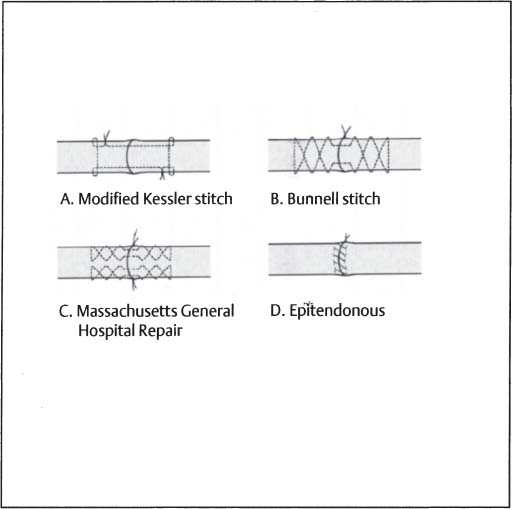

Tendon injuries of the forearm and hand range from simple an incomplete laceration of a single tendon to maceration and structural loss of multiple musculotendenous units. The mechanism of injury dictates the method of repair. Simple tendon lacerations are repaired directly with any familiar tendon repair technique (Fig. 16–1). The repair of tendon lacerations that are the result of blast and avulsion injuries is usually delayed because the extent of tendon damage is not immediately known. A delay of 3 to 4 weeks allows the determination of viable tendon, at which point, tendon reconstruction with tendon grafts is performed. Over the course of the delay, the tendon path and muscle length can be preserved utilizing Silastic (Dow Corning, Midland, MI and Barry, UK) tendon rods sutured to the injured tendon ends.

Figure 16–1 Tendon injury repairs. (A) Modified Kessler stitch. (B) Bunnell stitch. (C) Massachusetts General Hospital repair. (D) Epitendonous suture.

Extensor Tendon Injuries

Extensor Tendon Injuries

Patients with extensor tendon injuries present with obvious lacerations over the involved tendon, or palpable pain in the region of a closed injury. The resting hand position will display the involved digit in flexion secondary to the loss of the counterbalancing extensor. The patient will also be unable to extend the involved digit actively while the palm of the hand is face down on a flat surface (tabletop test).

Extensor tendon injuries are commonly the result of open lacerations, but also occur secondary to a variety of closed etiologies. Closed traumatic rupture of the extensor tendon includes but ins’t limited to: rupture of the extensor tendon at distal insertion of the distal phalanx (mallet finger) or central slip from the dorsum of the middle phalanx (boutonnière deformity), and rupture of the extensor pollicis longus associated with radius fractures. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis develop attrition ruptures at multiple levels that can also present in a similar fashion.

Anatomy

The extensor compartments of the hand are separated into six dorsal compartments:

• Abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis

• Extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis

• Extensor pollicis longus

• Extensor indicis and extensor digitorum communis

• Extensor digiti minimi (quinti)

• Extensor carpi ulnaris

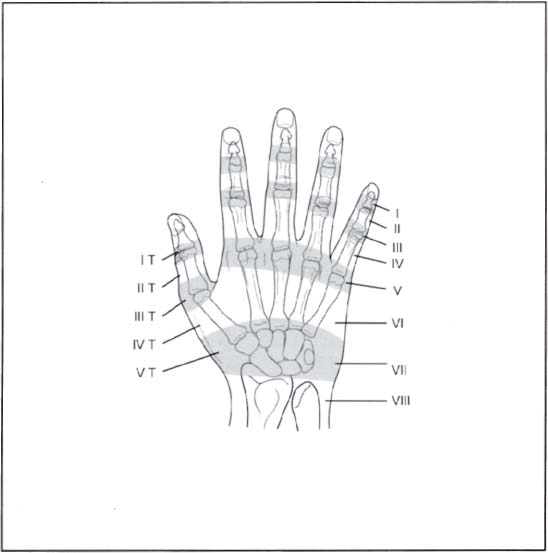

Longitudinally the extensor tendon is divided into nine zones from its course from the muscle to insertion into the distal phalanx (Fig. 16–2):

Zone I Distal interphalangeal joint

Zone II Middle phalanx

Zone III Proximal interphalangeal joint

Zone IV Proximal phalanx

Zone V Metacarpophalangeal joint

Zone VI Metacarpal

Zone VII Carpus

Zone VIII Distal forearm

Zone IX Musculotendinous junction proximal forearm muscle

The thumb has only five zones (Fig. 16–2):

Zone I Interphalangeal joint

Zone II Proximal phalanx

Zone III Metacarpophalangeal joint

Zone IV Metacarpal joint

Zone V Carpus

Figure 16–2 Extensor tendon zones.

The extensor tendon zones are a useful tool for describing the level of injury; they also correlate to functional prognosis. For ease of reference, the odd-numbered zones are located over the joints and the even-numbered zones are located over the bone.

In the proximal forearm, the extensor digitorum communis tendons arise from a common muscle belly and disallow independent extension of the middle and ring fingers. The exceptions are the index and small fingers, which have their respective independent extensors (extensor indicis proprius, extensor digit quinti. In zone V, the juncture tendinea connect the long, ring, and small finger tendons allowing ~30 degrees of flexion of the MCP joint even if the specific extensor digit to that tendon is cut. This anatomical configuration may confuse physical examination findings when obvious lacerations suggest proximal injury.

Timing of Repair

The timing of a repair depends primarily on the extent of the injury. Simple extensor tendon lacerations may be repaired easily in the emergency room with adequate local anesthesia. However, complex injuries of multiple tendons at many levels or with gross contamination require repair in the operating room, which allows the patient the benefit of sustained anesthesia in a tourniquet-controlled environment. Tendon injuries that are not associated with ischemicrelated injury to the hand or digit are repaired within one week. If it is not feasible to repair the tendon at the initial evaluation, the wound is irrigated and temporarily closed and the patient is placed in a volar splint with wrist, MP, and IP joints in slight extension.

Treatment

Due to the complex architecture of the extensor tendon, the treatment regimen and aftercare is dependant on area of injury. Generally, complete open lacerations are repaired acutely, while closed and partial (<50%) injuries can be treated with appropriate splinting to allow healing.

Zone 1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree