Granulomatous and Neutrophilic Disorders

Pamela Fletcher

Diane Solderitsch

In dermatology, many disorders have similar histologic findings of cutaneous inflammation, but the clinical presentations are dissimilar and causes are often unknown. These disorders are grouped histologically into categories of granulomatous and neutrophilic dermatoses. This chapter will deal with the most common conditions found in each of these categories, defining clinical presentations, diagnosis, and management.

NONINFECTIOUS GRANULOMATOUS DISORDERS

Skin conditions in this category are disorders of Langerhans cells and macrophages. Histiocytes are a type of macrophage and play an important role in the body’s immune system. In response to inflammation or infection, these histiocytes aggregate and form granulomas in the skin.

Granuloma Annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common, self-limiting inflammatory process affecting the dermis, with females affected twice as often as males. The localized form of GA is most common in patients under the age of 30 years. Although it has been linked with diabetes mellitus (DM), there is no evidence to support it. However, there is a correlation between DM and generalized or disseminated GA, occurring often in 30- to 60-year-olds. Patients with HIV commonly present with generalized GA. Atypical forms of GA have been associated with paraneoplastic granulomatous reactions to Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, solid organ tumors, and mycosis fungoides.

Pathophysiology

The cause of GA is unknown but may be related to vasculitis, trauma, monocyte activation, or delayed hypersensitivity reaction in the skin. There is a degeneration of collagen and accumulation of mucin. Histiocytes are palisaded (elongated and perpendicular in the superficial and mid-dermis).

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of GA varies widely. The term annulare refers to the round or arciform shape of the lesions, which are often erythematous, dome-shaped papules that form a circle with central clearing (hence its frequent diagnosis as ringworm) or faintly erythematous depression at the center. Lesions may be asymptomatic or pruritic.

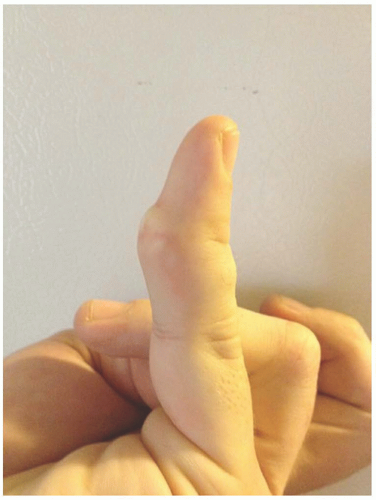

Localized

The localized form usually starts as a small ring of skin color or lightly erythematous papules favoring the dorsal surfaces of hands, feet, or extensor surfaces of the arms (especially the elbows) or legs (Figure 20-1). Over several weeks, lesions coalesce and evolve into annular plaques, which undergo central involution and increase in diameter from 0.5 to 5 cm over several months. It may also present as brownish-red plaques and papules that can be difficult to detect on dark skin.

Generalized

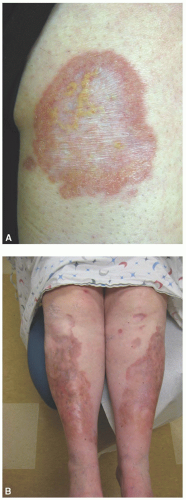

The generalized form of GA (15% of cases), typically presenting on the trunk and extremities of middle-aged Caucasian women, can be cosmetically distressing. Lesions are usually red to violaceous macules, patches, or flat, slightly elevated papules, which may be either pruritic or asymptomatic (Figure 20-2).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Granuloma annulare

Tinea corporis

Lichen planus

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL)

Sarcoidosis

Secondary syphilis

Diagnostics

Diagnosis is usually made based on clinical presentation but can be confirmed with a punch biopsy if there is any doubt. Histologically, there are two patterns of GA, palisading and interstitial (such as interstitial GA). The latter should not be confused with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis. A KOH slide can help differentiate GA from tinea corporis, which has scale. Serologies can be ordered if syphilis is considered.

Management

Localized GA is usually not treated unless it concerns the patient due to appearance. Treatment is provided mainly for cosmetic purposes

and often with less than optimal results. First-line treatment includes high-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS) with or without occlusion, intralesional (IL) corticosteroid injections into the elevated portions of the lesions with triamcinolone acetonide (depending on location), or cryotherapy. Risks from these treatments include atrophy and scarring. Off-label use of tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, and imiquimod has been reported to have some efficacy. Second-line treatment that may be used in dermatology for severe localized GA includes systemic agents such as isotretinoin, antimalarials, cyclosporine or dapsone.

and often with less than optimal results. First-line treatment includes high-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS) with or without occlusion, intralesional (IL) corticosteroid injections into the elevated portions of the lesions with triamcinolone acetonide (depending on location), or cryotherapy. Risks from these treatments include atrophy and scarring. Off-label use of tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, and imiquimod has been reported to have some efficacy. Second-line treatment that may be used in dermatology for severe localized GA includes systemic agents such as isotretinoin, antimalarials, cyclosporine or dapsone.

FIG. 20-2. The generalized form of GA presents as chronic lesions, as on legs of this 62-year-old woman with diabetes. |

Treatment for generalized GA is difficult and the patient should be referred to a dermatologist for photochemotherapy using oral psoralen and ultraviolet light A (PUVA), CO2 laser, or systemic agents.

Special considerations

Lesions in children aged 2 to 5 years may present as deep, painless, skin-colored papules near joints, on the palms, soles, or buttocks. The generalized form in older patients may present as hundreds to thousands of small, flesh-colored papules in symmetric distribution on the trunk and extremities.

Prognosis and complications

Most lesions resolve spontaneously after several months to several years (50%-75% clear within 2 years) but may recur. The generalized form may last for an extended period of time. GA does not typically result in scarring but may occur secondary to treatments.

Referral and consultation

Refer to dermatology if the diagnosis is unclear or when lesions are unresponsive to first-line treatment. Clinicians providing IL triamcinolone should be experienced to minimize side effects.

Patient education and follow-up

Educate patients about the disease; provide anticipatory guidance and reassurance. They should be alert for side effects to medications and treatments, seeking appropriate intervention if they occur. Patients may become anxious if they develop multiple lesions, the lesions involve several areas, and/or lesions expand.

Patients are often evaluated by a dermatologist and may be monitored occasionally since GA is benign and self-limiting. Patients with generalized GA should have regular checkups and be monitored for side effects of immune-modifying medications. Any signs or symptoms of infection should be evaluated immediately and care coordinated with a dermatologist.

Actinic Granuloma (of O’Brien)

A granulomatous skin disease first described by Dr. O’Brien in 1975, actinic granuloma is also called annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. There is some controversy as to whether it is a variant of GA. Actinic granuloma is uncommon and occurs more frequently in middle-aged individuals with a history of excessive sun exposure. A typical patient is a fair-skinned female aged 40 to 50 years and living in a sunny area.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of actinic granuloma is unknown, but it is thought to be an inflammatory response to sun exposure.

Clinical presentation

As the name implies, lesions present as asymptomatic annular plaques on sun-exposed areas. Lesions may be flesh or pink color with classic GA morphology (Figure 20-3).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Actinic granuloma

Tinea corporis or capitis

Granuloma annulare

Necrobiosis lipoidica

Discoid lupus

Diagnostics

As with GA, diagnostic tests are usually not indicated but may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Management

First-line treatments for actinic granulomas are similar to GA, but the response is usually poor. Other treatments, such as phototherapy and antimalarials, have been reported. Sun protection is important to prevent new lesions.

Prognosis and complications

Most lesions resolve spontaneously after several months to several years. Lesions may recur or spread secondary to sun exposure. Actinic granuloma does not usually cause scarring. Secondary scarring may occur with atrophy from IL corticosteroid injections.

Referral and consultation

Refer to dermatology if the diagnosis is unclear, lesions are atypical, or for second-line therapy. Patients may desire consultative care for cosmetic treatment.

Patient education and follow-up

Follow-up care of patients with actinic granuloma is same as GA. Emphasis should be placed on patient education for sun protection to avoid the development of new lesions.

Foreign-Body Granuloma

Foreign-body granulomas are common skin reactions that can occur from exogenous or endogenous sources. They can occur in any age group, but exogenous sources are more common during working years since occupational injury is the most common cause.

Pathophysiology

Initially, foreign-body granulomas are caused by trauma that develops into granulomas, from either allergic or nonallergic inflammation. It is a chronic process of granulomatous changes. Any exogenous source such as glass, metal, wood, ink from tattoos, collagen injections, suture material, or inorganic materials that enter the body (either accidentally or by insertion) can cause a foreign-body granuloma. The increasing use of dermal fillers for cosmetic enhancements has also been associated with foreign-body granulomatous reactions (see chapter 23). Endogenous or biologic sources, such as ruptured hair follicles or cysts, are the most common internal causes of foreign-body granulomas. Although the body is the source of the material, the immune system responds as though it is foreign.

Clinical presentation

Foreign-body granulomas usually present as an inflamed nodule or plaque usually accompanied by tenderness. In the early stage, there can be purulence. In time, the chronic lesion may become firm, sclerotic, or scarred (chronic stage) (Figure 20-4).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Foreign-body granuloma

Pyogenic granuloma

Basal cell carcinoma

Contact dermatitis

Pseudofolliculitis barbae

Acne keloidalis nuchae

Cellulitis

Osteomyelitis

Cyst

Diagnostics

Accurate diagnosis depends on history taking. Biopsy may be helpful, and an x-ray may identify the foreign body if it is substantial in size and radiopaque. A punch biopsy may be curative.

Management

Management depends on symptoms and patient preference. Surgery may be necessary for removal of the foreign body. Lasers have been used for tattoo removal with variable results.

Prognosis and complications

A foreign-body granuloma is not life- or limb-threatening but may limit function, create annoyance, or be cosmetically displeasing. Complications from surgical removal include risk of infection and scarring.

Referral and consultation

Foreign-body granulomas of the hands, feet, or digits may require consultation with a specialist such as a hand surgeon or orthopedic surgeon. Cosmetically sensitive areas may require consultation with a plastic surgeon or dermatologist.

Patient education and follow-up

Emphasis should be placed on prevention of new lesions from repeated exposure. Follow-up with their primary care provider (PCP) or specialist should be as needed.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica

NL is a granulomatous skin disease that is commonly associated with DM, hence the previous nomenclature NL diabeticorum. Nearly 75% of those with NL have or will develop DM, with skin lesions that may appear years in advance of the diagnosis. Conversely, only a very small percentage of diabetics develop NL. The onset is highest during the third or fourth decade, with female predominance of 3:1.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of NL is unknown, as with other noninfectious granulomatous diseases. Histologic analysis shows a degeneration of collagen (necrobiosis) and granulomatous inflammation.

Clinical presentation

Skin lesions start as small, violaceous, round or oval, sharply defined patches or thin plaques favoring the anterior lower legs (Figure 20-5). Then slowly, the lesion expands in size, with the borders remaining red and center evolving into a waxy yellow/brown color. The surface is often shiny with telangiectasias present (Figure 20-6). Lesions may

be asymptomatic or can have tenderness, pruritus, itching, paresthesias, or numbness. Trauma in the area frequently leads to nonhealing ulcers.

be asymptomatic or can have tenderness, pruritus, itching, paresthesias, or numbness. Trauma in the area frequently leads to nonhealing ulcers.

FIG. 20-5. Early necrobiosis lipoidica can begin as a violaceous plaque, often found on the anterior lower legs. |

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Necrobiosis lipoidica

Granuloma annulare

Diabetic dermopathy

Stasis dermatitis

Erythema nodosum (early)

Infectious granulomas

Cutaneous sarcoidosis

Nonmelanoma Skin cancer

Morphea

Lichen sclerosis

Pretibial myxedema

Xanthomas

Management

Lesions of NL are often very resistant to treatment. The focus of therapy should be to prevent leg ulcers and to heal them quickly should they develop. Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for NL. Potent TCS used daily for 2 to 4 weeks is recommended for active areas (usually borders) of large, thick plaques. It provides little improvement and may even cause a worsening of atrophy in “burnt-out” lesions of NL. IL triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg /mL), which can be diluted with lidocaine or sodium chloride to reduce risk for atrophy, may be used for smaller lesions or injected into their erythematous border. Oral corticosteroids can be effective in healing ulcerations. The benefits and risk of this systemic therapy should carefully be considered in diabetic patients. Ulcerations from NL have been reported to respond to off-label treatment with pentoxifylline, as well as aspirin and dipyridamole. Other medications include cyclosporine, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, PUVA, and hydroxychloroquine. Skin grafting may be necessary for extensive, nonhealing ulcers.

Special considerations

The clinical presentation of NL is distinctive, so a biopsy is usually not needed and may result in additional nonhealing ulcers, especially in diabetic patients.

FIG. 20-6. A: Necrobiosis lipoidica can expand with waxy, yellow centers and erythematous borders. B: Larger lesions may become shiny and atrophic with telangiectasias. |