Genital and oral problems

Sheelagh M Littlewood MBChB, FRCP

Introduction

Genital and oral disease is often regarded as a difficult subspeciality. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, the appearance of dermatoses on genital skin may be very ‘nonspecific’ and the characteristics of disease seen elsewhere may be absent in this area. It is important, therefore, to search for clues to diagnoses of diseases of oral and genital skin on nonmucosal surfaces.

Many diseases of the genital area result in scarring that would not be expected to occur in nongenital disease. This results in a ‘common end-stage’ appearance of shiny, smooth, featureless scarred tissue with little evidence of the original underlying disease, but could equally represent, for example, lichen sclerosus or lichen planus.

As the area is moist, occluded and subjected to friction and chronic irritation from urine and faeces, it is an excellent environment for infection and this often complicates other disease processes. It is important to remember that patients often attribute disease in the genital area to poor hygiene and as a result overwash the area, adding an irritant dimension to an already complex picture.

Many doctors and most patients are not familiar with the normal variation in the anatomy of this area and have little, or no, experience of normal appearances in an asymptomatic patient. This can result in misdiagnosis and unwarranted anxiety.

Lichen sclerosus

Introduction

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory condition which tends to produce scarring that preferentially affects the genital area. It is 6-10-fold more prevalent in women. The aetiology is unknown, but a strong association with autoimmune disease is recognized. Occasionally, the disease can be asymptomatic and found purely by chance. However, the vast majority of patients complain of pruritis and soreness. In men, the condition only affects the uncircumcised. It can be asymptomatic but tends to produce not only itching and burning, but also bleeding, blistering, sexual dysfunction, and difficulties with urination when the urethral meatus is involved.

Clinical presentation

In either situation the classical features are pallor and atrophy as demonstrated by a wrinkling of the skin and textural change, plus an element of purpura, erosions, fissuring, telangiectasia, hyperkeratosis, bullae, or hyperpigmentation. Atrophy results in loss of the labia minora and burying of the clitoris, and pseudocysts of the clitoral hood from adhesions can occur.

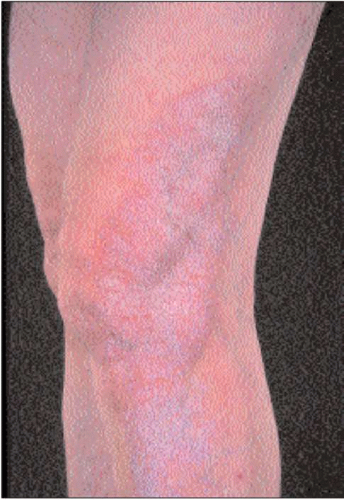

The introitus can be significantly reduced and perineal involvement produces a classic figure-of-8 shape, extending around the anus (7.1, 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4). The histopathology can be very distinctive and can be useful in differentiating the condition from lichen planus, lichen simplex, and cicatricial pemphigoid. Typical findings are epidermal atrophy, hydropic degeneration of the basal layer, hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging, oedema, and homogenization of collagen in the upper dermis with an inflammatory infiltrate below. The dermis shows sparse elastic fibres with swollen collagen

fibres, dilatation of blood vessels, and extravasation of red blood cells. There is often localized or diffuse squamous hyperplasia which may be the result of chronic scratching, but equally can indicate malignant transformation. There should be a low threshold for biopsy, sometimes repeatedly, of hyperkeratotic suspicious areas to exclude squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

fibres, dilatation of blood vessels, and extravasation of red blood cells. There is often localized or diffuse squamous hyperplasia which may be the result of chronic scratching, but equally can indicate malignant transformation. There should be a low threshold for biopsy, sometimes repeatedly, of hyperkeratotic suspicious areas to exclude squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

7.1 Perianal LS. |

7.2 Juvenile LS. |

7.3 Nongenital LS on the leg. |

7.4 Extensive LS with petechiae and marked scarring. |

Management

First-line treatment is now recognized as ultra-potent topical steroids, 0.05% clobetasol propionate, for 3 months initially. It is important to advise on avoiding irritants, and the use of bland emollients and soap substitutes. Previous treatments such as topical testosterone have been shown to be ineffective. Surgery is not indicated for uncomplicated disease but is useful for complications such as introital narrowing and removal of pseudocysts. The disease runs a chronic course and the development of SCC is well recognized, with an incidence of 4-5%. Topical tacrolimus has also been used but its place has yet to be fully determined.

Lichen planus

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory dermatosis that is believed to account for 1% of new cases seen in dermatology outpatients. Typical skin lesions are violaceous, itchy, flat-topped papules (7.5). The aetiology of LP is unknown, but it is believed to be an autoimmune disease. It can affect the skin or mucous membranes or both simultaneously.

Clinical presentation

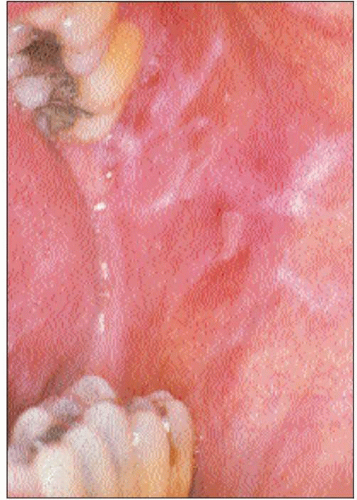

Oral LP

Oral LP is one of the commoner conditions seen in oral medicine clinics. The prevalence ranges from 0.5% to 2.2% with a slightly higher prevalence in women.

There are three classes of clinical disease:

Reticular, which is a net or plaque-like area which is often painless and is seen in about 20% of patients with typical cutaneous lichen planus (7.6).

Erosive/atrophic, in which erythematous areas of thinned but unbroken epithelium occur. This includes the gingival condition of desquamative gingivitis.

Ulcerative lesions, in which the epithelium is broken.

7.5 Polygonal flat-topped papules of LP on the wrist. Wickham striae are easily seen. |

7.7 Chronic LP of the anogenital area with hyperpigmentation and gross scarring. |

The latter two are typically very painful and run a chronic relapsing course. More than one type can exist at any time and can affect the buccal mucosa, lateral border of the tongue, and gingiva.

Genital LP

LP can affect the perigenital skin with a classic presentation of violaceous flat-topped papules (7.7). It can also affect the mucosal side of the labia, where it typically produces a glazed erythema, which bleeds easily on touch and tends to erode, hence the term ‘erosive LP’. The early glazed erythema is very nonspecific and is difficult to diagnose correctly as it can resemble a number of other inflammatory diseases. However, LS tends to affect the outer aspect of the labia minora, as opposed to LP, which affects the inner. In a typical case of mucosal LP, the erythema is bordered by a white, occasionally violaceous border, which can be an important diagnostic clue. If present then this is the ideal place to biopsy. However, it is often absent resulting in diagnostic difficulty. One should always examine the mouth and other cutaneous sites, and look for evidence of vaginal disease, as this can be very helpful in making the diagnosis.

The erosive form of genital LP can be associated with a similar condition in the mouth, the vulvo-vaginal-oral syndrome.

The erosive form of genital LP can be associated with a similar condition in the mouth, the vulvo-vaginal-oral syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree