Flap Coverage of Fingertip Injuries

Kate Elzinga

Kevin C. Chung

DEFINITION

Fingertip injuries are defined as injuries that occur distal to the insertion of the flexor and extensor tendons of the finger.1

Fingertip injuries are the most common hand injuries; the fingertips are relatively unprotected compared to the rest of the hand.

The fingertip plays an important role in fine motor skills, precise sensation, and hand aesthetics. Reconstruction of fingertip injuries can restore form and function for injured patients.

The goals of fingertip reconstruction include the following:

Durable coverage

Preservation of sensation

Preservation of length

Maintenance of distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint function

Optimized appearance

Minimized donor-site morbidity

Permitting early return to work and recreational activities

Minimizing pain, in the short and long term

Fingertip flaps are used to cover injuries with exposed bone and tendon. Local (V-Y advancement) and regional (thenar, cross-finger) flaps are useful options.

Local flaps, such as the Atasoy-Kleinert V-Y advancement flap,2 are the simplest flaps used for reconstruction; immobilization is not required and donor-site morbidity is minimal.

Regional flaps are employed when local flaps are not available because of the injury geometry (regional flaps are best used for volar oblique injuries) and size (local flaps can only be advanced 1 cm). Regional flaps require two-stage procedures and immobilization of the injured, and often adjacent, finger.

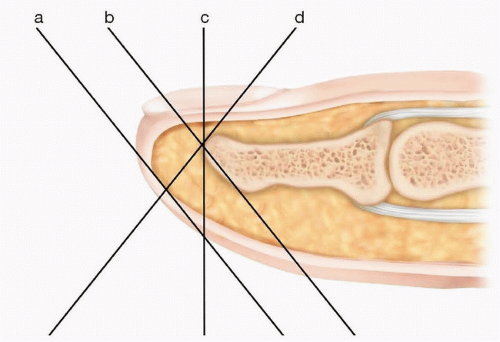

ANATOMY

The volar fingertip is covered with glabrous skin. The epidermis is thick, and papillary ridges are prominent.

The fingertip pulp is composed of fibrofatty tissue that is stabilized volarly by fibrous septa that run from the distal phalanx periosteum to the dermis and laterally by Grayson and Cleland ligaments.

The proper digital nerve trifurcates distal to the DIP joint, sending branches to the nail bed, distal fingertip, and volar pulp. The proper digital artery also trifurcates at this level, sending two branches dorsally and one branch laterally.

PATHOGENESIS

Trauma is the most common cause of fingertip injuries.3

Common mechanisms of fingertip injuries include sharp injuries from a knife, power tool, or lawn mower and crush injuries from closing a door, a strike with a hammer, dropping a heavy object, becoming trapped in machinery, or sporting activities.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A careful patient history and physical examination help determine which flap options are suitable for a particular patient.

Some patients may prefer rapid return to their work and avocations and will refuse fingertip reconstruction, opting for fingertip amputation instead.

A focused hand history must include age, sex, hand dominance, and occupation and recreational activities. The patients’ goals are explored, including their need to return to work, their availability and willingness to undergo secondary procedures and hand therapy, and the importance of appearance.

Aesthetic outcome may be more important for females and patients from certain Asian cultures.

Important considerations from the patient’s past medical history include smoking, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, connective tissue disorders, arthritis, Dupuytren disease, and previous hand injuries.

The presence of comorbidities may affect reconstruction options offered given their effect on flap vascularity and wound healing.

Key injury factors to consider include the time of injury, mechanism of injury (sharp vs crush), contamination, and associated injuries.

On physical examination, the defect size is measured. The level of the injury is assessed clinically and using radiographic imaging.

Missing tissue (skin, pulp, bone, nail) and exposed structures are documented. The geometry of the injury is assessed and classified as volar oblique, transverse, or dorsal oblique (FIG 1).1

Tissue contamination is assessed, and any early signs of infection are noted.

Surrounding tissues and digits are examined as potential donor sites.

The integrity of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and extensor digitorum communis (EDC) tendons is tested; it is important not to miss an associated jersey finger or mallet finger injury.

IMAGING

Plain radiographs can identify fractures of the finger and the presence of a foreign body.

Three radiographic views of the finger and amputated part should be obtained following a fingertip amputation.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Small defects (less than 1 cm2) with no exposed bone can be treated nonoperatively.4

Dressing changes are performed daily to maintain a clean moist wound bed as the wound heals by secondary intervention over several weeks.

Outcomes are typically excellent in these cases as glabrous sensate skin heals over the exposed soft tissues.5

Immobilization is not required and range-of-motion exercises are performed throughout.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs) can be considered for coverage of large soft tissue avulsion injuries without exposed bone or tendon.

The glabrous skin of the hypothenar eminence is the preferred harvest site for volar skin defects. Palmar skin is an excellent donor site for structure and color matching of the fingertip skin; the resultant scar from the palm can be rather imperceptible.

Skin grafting promotes faster wound coverage, but sensation, color, and durability are inferior to secondary healing.5

Replacement of amputated tissue as a composite graft may be considered; outcomes are best for pediatric patients younger than 6 years of age within 5 hours of the amputation.6

Fingertip flaps preserve finger length. Early coverage of exposed bone and tendon decreases the risk of osteomyelitis and tendon desiccation. Protecting the terminal phalanx with a flap preserves bone length that supports the overlying nail.

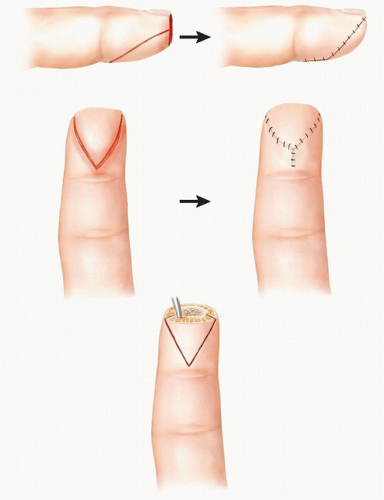

The volar V-Y advancement flap (FIG 2) is well suited for transverse and dorsal oblique fingertip injuries.

The V-Y flap can cover defects of up to 2 cm2 and can be advanced 1 cm.

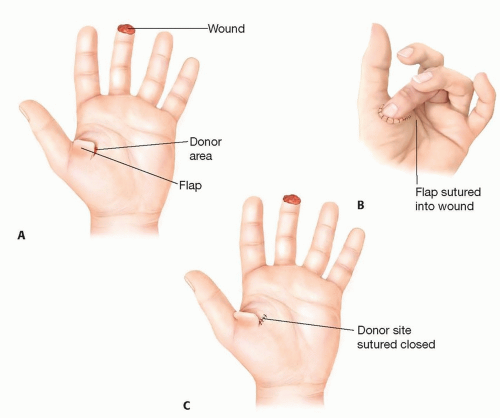

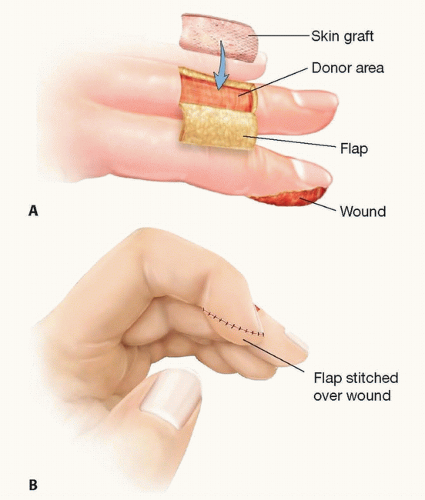

The thenar flap (FIG 3) and cross-finger flap (FIG 4) provide coverage for volar oblique injuries. The thenar flap provides improved sensory recovery and has a less conspicuous donor site compared with the cross-finger flap but requires greater finger flexion for inset, which can cause joint stiffness, particularly in elderly patients. However, the lack of donor-site morbidity and predictable outcomes makes the thenar flap our first choice, if possible, over the cross-finger flap.

The cross-finger flap can be used for defects up to 1.5 × 2.5 cm in size.

The thenar flap can be designed to cover the entire pulp with a width of up to 2 cm.

Preoperative Planning

The risks and benefits of flap coverage for fingertip injuries are discussed with the patient during their initial assessment and reviewed again prior to their surgery.

Fingertip and/or the removal of exposed bone followed by secondary intention healing are discussed as alternative treatment options.

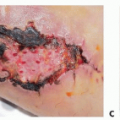

FIG 4 • A. The cross-finger flap is composed of skin and subcutaneous tissue from the dorsal middle phalanx of the adjacent finger. B. The flap donor site is closed with an FTSG.

Benefits of flap coverage include preservation of finger length, provision of durable soft tissue coverage, and good aesthetic results.

Drawbacks include the creation of a donor site, the possibility of flap failure, and the need for longer immobilization.

Cross-finger and thenar flaps require the injured digit to be placed in flexion, which can lead to postoperative stiffness.

These flaps are contraindicated in patients at high risk of joint contractures, eg, elderly patients with arthritis or Dupuytren disease.

The thenar flap cannot be performed in patients without adequate passive metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and interphalangeal joint flexion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree