Nonsurgical rhinoplasty is an innovative technique that allows for temporary modification of the nose to improve esthetic appearance and function. As with any filler augmentation, a thorough understanding of complex nasal anatomy is key to obtain optimal results while reducing risk of complications. Injection strategy is dependent on overall desired goals and can vary when addressing the radix, middle vault, and tip. While the procedure has a relatively low-risk profile, rapid recognition and early intervention of vascular complications is crucial.

Key points

- •

Nonsurgical rhinoplasty (NSR) utilizes filler injection to augment and improve aesthetic concerns of the nose.

- •

Hyaluronic acid is the most commonly used material.

- •

Advantages include low cost, quick recovery times, convenience, and low risk profile without the added risk of general anesthesia.

- •

Injection techniques closely mirror graft placement in traditional rhinoplasty.

- •

Vascular compromise leading to blindness is a major complication and requires immediate attention.

Introduction

Traditional rhinoplasty involves the surgical correction of nasal deformities to improve cosmetic appearance and/or functional status of the nose. Continuous innovation in the field has resulted in refinement of surgical techniques and approaches with the goal of producing natural results with minimal scarring and complications. Nonsurgical rhinoplasty (NSR) is a novel, popular approach that involves the injection of filler, most commonly hyaluronic acid (HA), into various areas to augment the nose and correct cosmetic concerns. Several advantages of this technique include natural results, lower associated costs, rapid recovery, ability to perform in the clinic, and temporary nature of the procedure, all without the added risks of general anesthesia and surgery. While there are a variety of injection techniques, an in-depth understanding of nasal anatomy is critical to achieve optimal results and reduce risks of significant adverse effects, namely vascular compromise.

Relevant anatomy

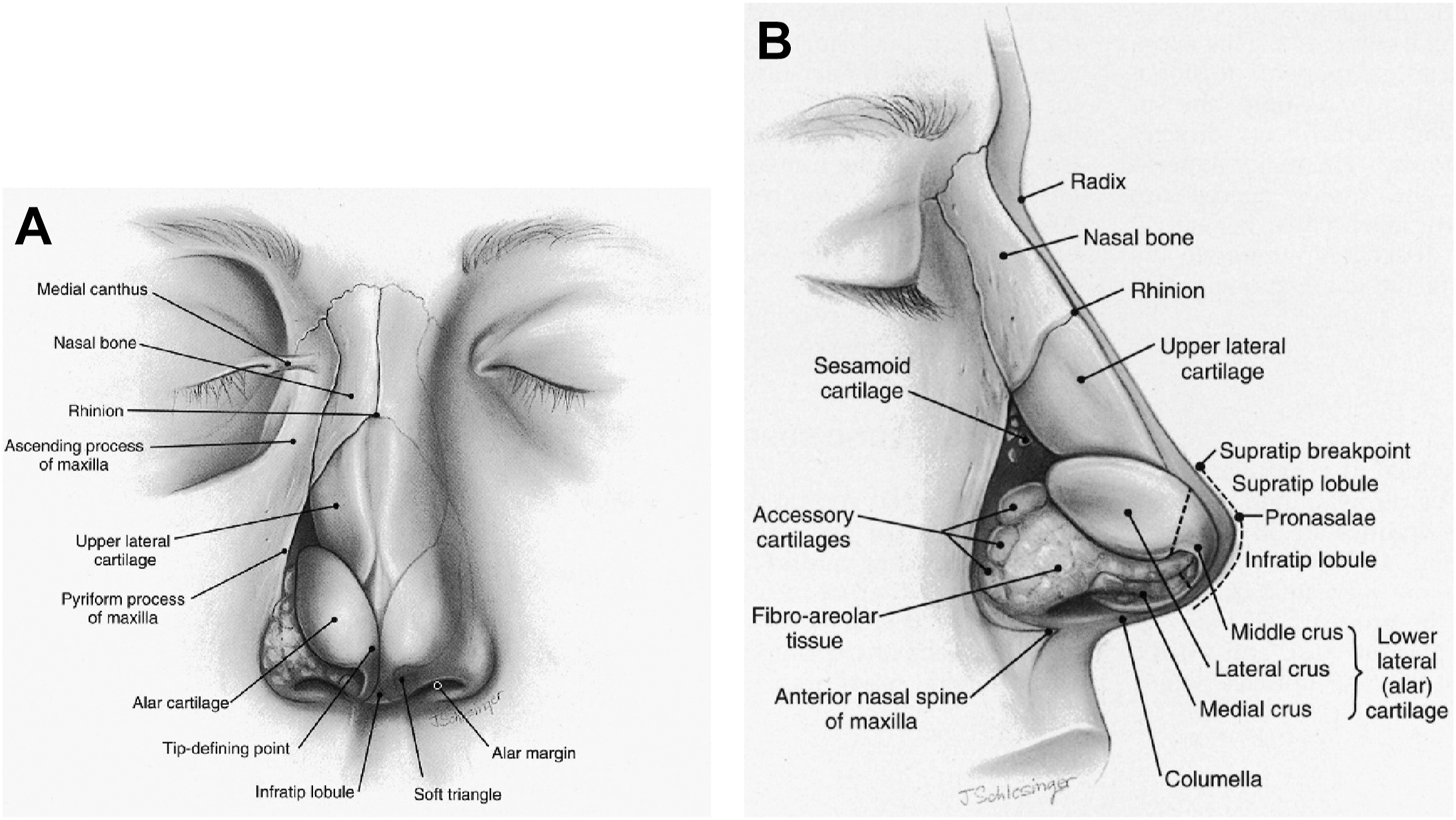

The nose can be best described in thirds comprising the bony upper third, the cartilaginous middle third, and the tip ( Fig. 1 A, B ). The upper third consists of paired nasal bones extending from the frontal bone toward the rhinion, or the junction of the nasal bone and the upper lateral cartilages (ULCs). The nasofrontal angle consists of 2 lines tangent to the glabella and to the nasal dorsum intersecting at the nasion, with the ideal angle dependent on gender and ethnicity [ ]. Nasal bones articulate with the lacrimal bone superolaterally, the nasomaxillary processes inferolaterally.

The middle third of the nose consists of paired ULCs, which articulate with the nasal bones and septum to form the keystone area. One critical area in the middle third is the internal nasal valve (INV), which is formed by the ULCs, septum, and head of the inferior turbinate. As the narrowest area in the nasal cavity, collapse in this area can lead to complaints of obstruction while exacerbating sinus and middle ear pathology [ ].

The tip consists of paired lower lateral cartilages (LLCs) formed from lateral, intermediate, and medial crura, which define tip shape, structure, and support. The medial crura join to form the columella with the caudal septal cartilage sitting just behind, extending from upper lip to the tip. The caudal border of the ULCs articulates with cephalic margins of the LLCs in the scroll area. The scroll; the shape, size, and strength of LLCs; and the attachment of medial crura to the caudal septum represent the 3 major tip support mechanisms of the nose. In addition, the minor support mechanisms include the anterior nasal spine, membranous septum, dorsal septum, lateral sesamoid cartilages, interdomal ligaments, and skin and soft tissue envelope [ ]. Understanding the intricate nuances of each unique nasal tip is essential to improving esthetic appearance while preserving function.

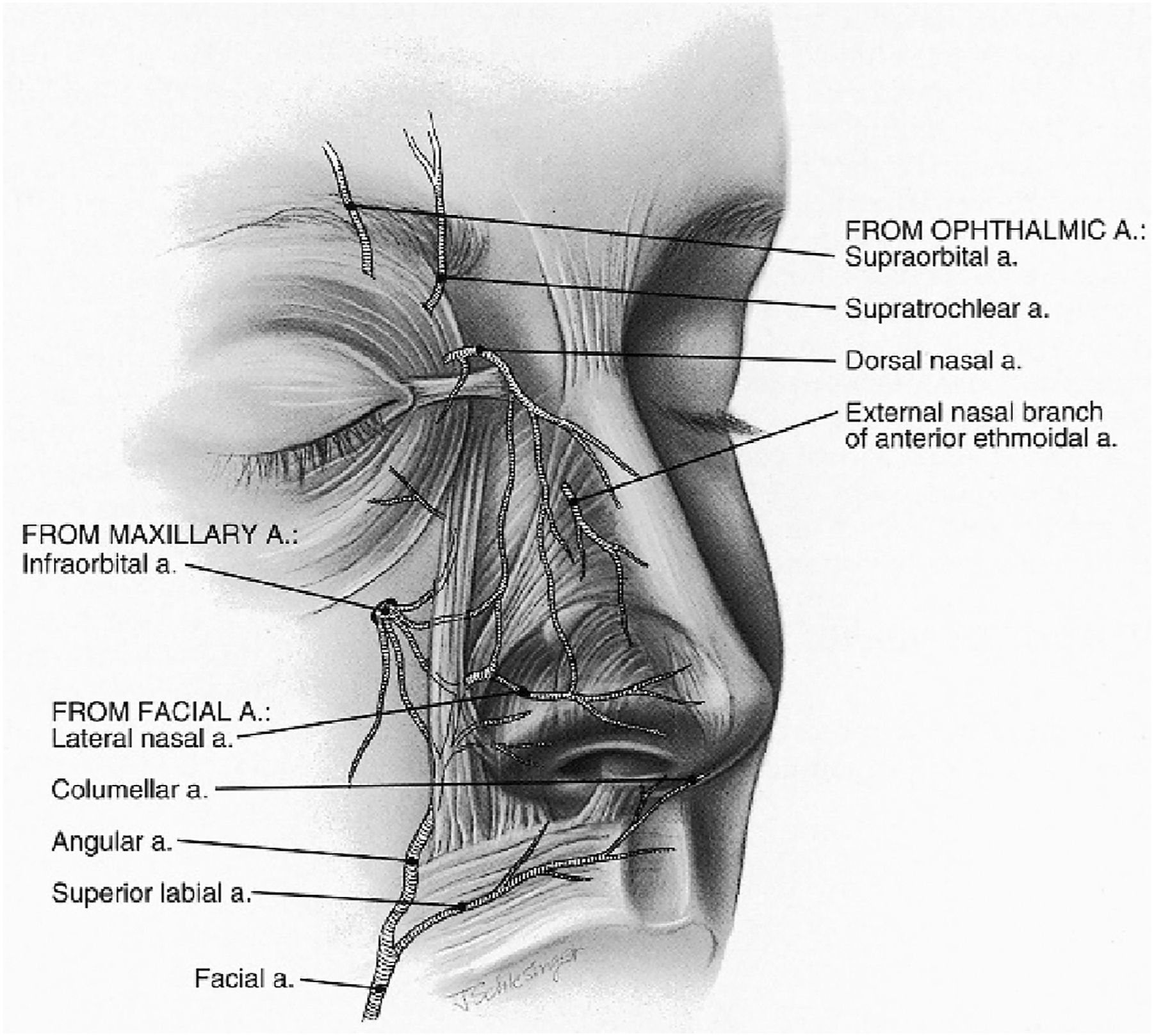

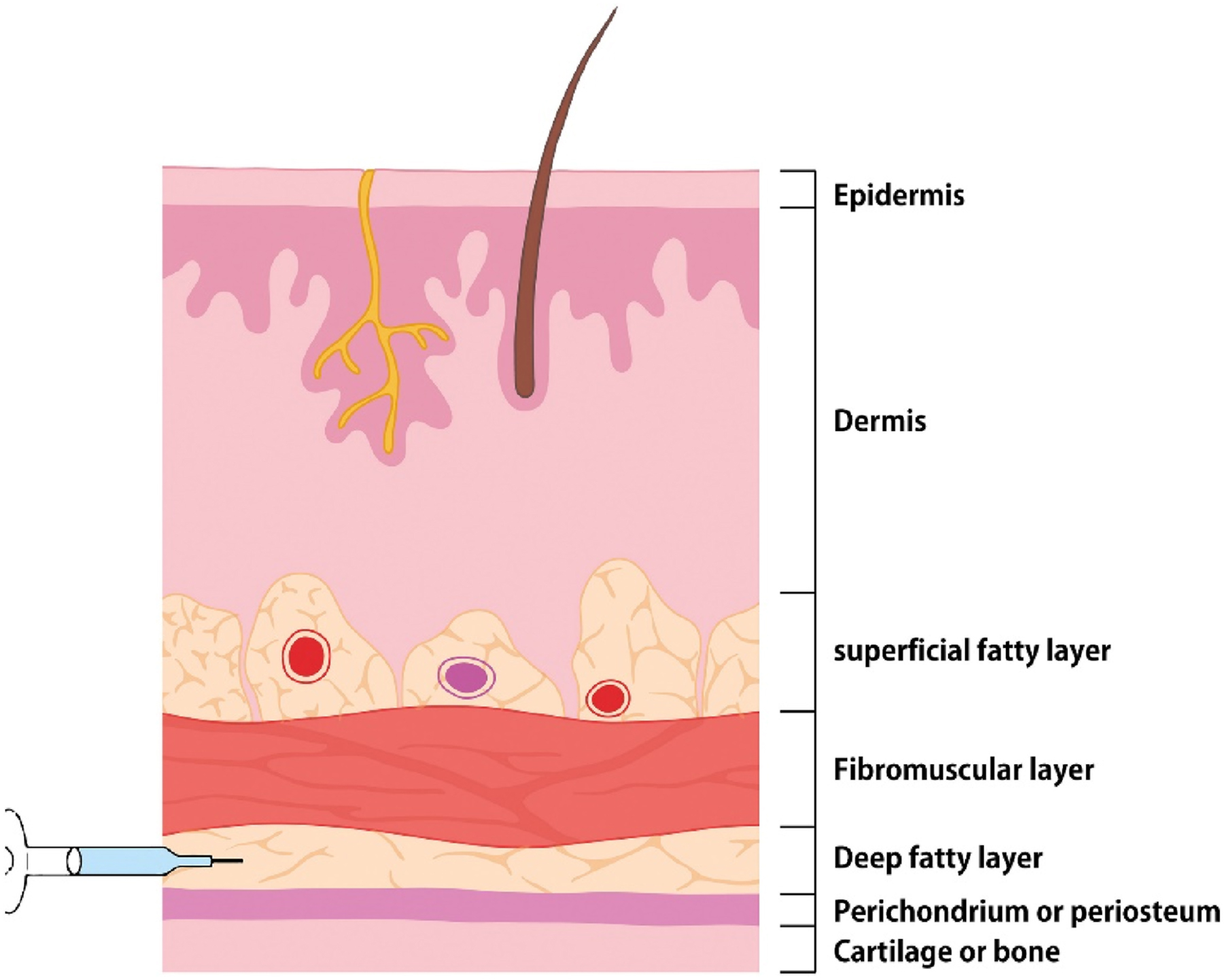

Layers of the nose include skin, superficial fat, fibromuscular layer (superficial musculoaponeurotic system [SMAS]), deep fatty layer (loose areolar tissue), and perichondrium [ ]. Skin is thickest at the radix and tip, while thinnest at the rhinion. Crucial blood vessels supplying the nose typically lie in the deep fatty layer along the lateral sidewalls of the nose. An understanding of the complex vascular supply to the nose is essential to avoiding filler-related complications with the acknowledgment that there are variations in individual anatomy ( Fig. 2 ). The ophthalmic artery branches into anterior ethmoid artery, posterior ethmoid artery, and dorsal nasal artery that supply the lateral nasal wall/septum, superior turbinate/septum, and dorsal aspect of external nose, respectively [ ]. The floor of the nose and internal structures receive blood supply from the greater palatine artery and sphenopalatine artery via the maxillary artery. The facial artery has multiple prevalent branches that supply the external nose. The alar and septal branches of the superior labial artery are responsible for alar and septal perfusion while the angular artery, which runs along the nasal sidewall, is responsible for tip, dorsum, and lateral wall supply [ ].

Filler selection

Many types of filler including silicone, HA, and calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHa) have been used over the years in NSR, with HA as the most common [ ]. When selecting an appropriate filler for NSR, ideal characteristics should include reversibility, long duration, and stiffness. Storage or elastic modulus (G′) is a rheological characteristic that represents the elastic behavior of the material and how likely it is to retain its shape [ ]. Higher G′ has an elevated resistance to deformation and increased stiffness as a result, making this feature an ideal option for NSR.

HA is a naturally occurring compound that is composed of polymeric disaccharides with the ability to form stable structures in aqueous solutions. Due to its low immunogenicity and relative ease of use, HA has been used in various areas of the face to enhance facial features [ ]. HA is a good choice for the precision required for NSR due to its low immunogenicity and high G’ options resulting in strong structural support, reversibility in event of adverse effects or patient preference, and low potential for tissue distortion. While CaHa has a significantly higher G′ than any HA product on the market, the ease of reversal makes HA a more common choice in practice today. In cases of complication, vascular injury, or patient dissatisfaction, reversibility offers an advantage to the patient and peace of mind to the injector. Compared to CaHa and other long-lasting semipermanent fillers, HA fillers can typically last between 6 and 12 months, depending on concentration, cross-linking, and density [ ]. Permanent fillers such as silicone, poly- l -lactic acid (Sculptra, Galderma, La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland), polymethylmethacrylate (Bellafill, Suneva Medical, CA, USA) should be avoided in the nose due to the potential for permanent complications including vascular injury and granulomas. Advantages and disadvantages of filler options should be thoroughly discussed with the patient, and optimal filler selection may depend on independent patient characteristics and preferences.

Patient selection

As with all cosmetic procedures, patient selection is one of the most critical aspects in achieving a positive outcome. In-depth knowledge of the strengths and limitations of NSR is absolutely critical in choosing patients who are optimal candidates for injection. At its most fundamental, NSR adds volume to the nose to help camouflage, blend, and/or balance the nose. It cannot make the nose smaller. Relationships such as raising dorsal height can give the illusion of smaller tip projection, but the fundamental length of the tip cannot be made smaller with NSR. This principle seems obvious to the reader but is worth emphasizing. Patients who desire a smaller overall nose (including smaller bridge height, smaller tip position, or shape) should be counseled that a surgical rhinoplasty may be the best option and referred for surgical consultation.

Injection technique

The procedure begins with a detailed conversation on ideal nose shape with the patient and obtaining informed consent. Local anesthetic ointment and ice to the nose may be applied for anesthesia and vasoconstriction, respectively. The nose should be cleansed thoroughly with antiseptic. The dorsal midline and ideal radix position should be marked to prevent asymmetry. A discussion of injection principles is warranted as they can help achieve an ideal outcome and minimize risk at the same time. The ideal layer for filler injection is just above the perichondrium or periosteum in the deep fatty layer as the superficial fatty layer and SMAS are rich in blood vessels ( Fig. 3 ). Deep injection, use of small needles, small boluses, and low injection pressure are all strategies to reduce the risk of vascular infiltration and will be discussed further.

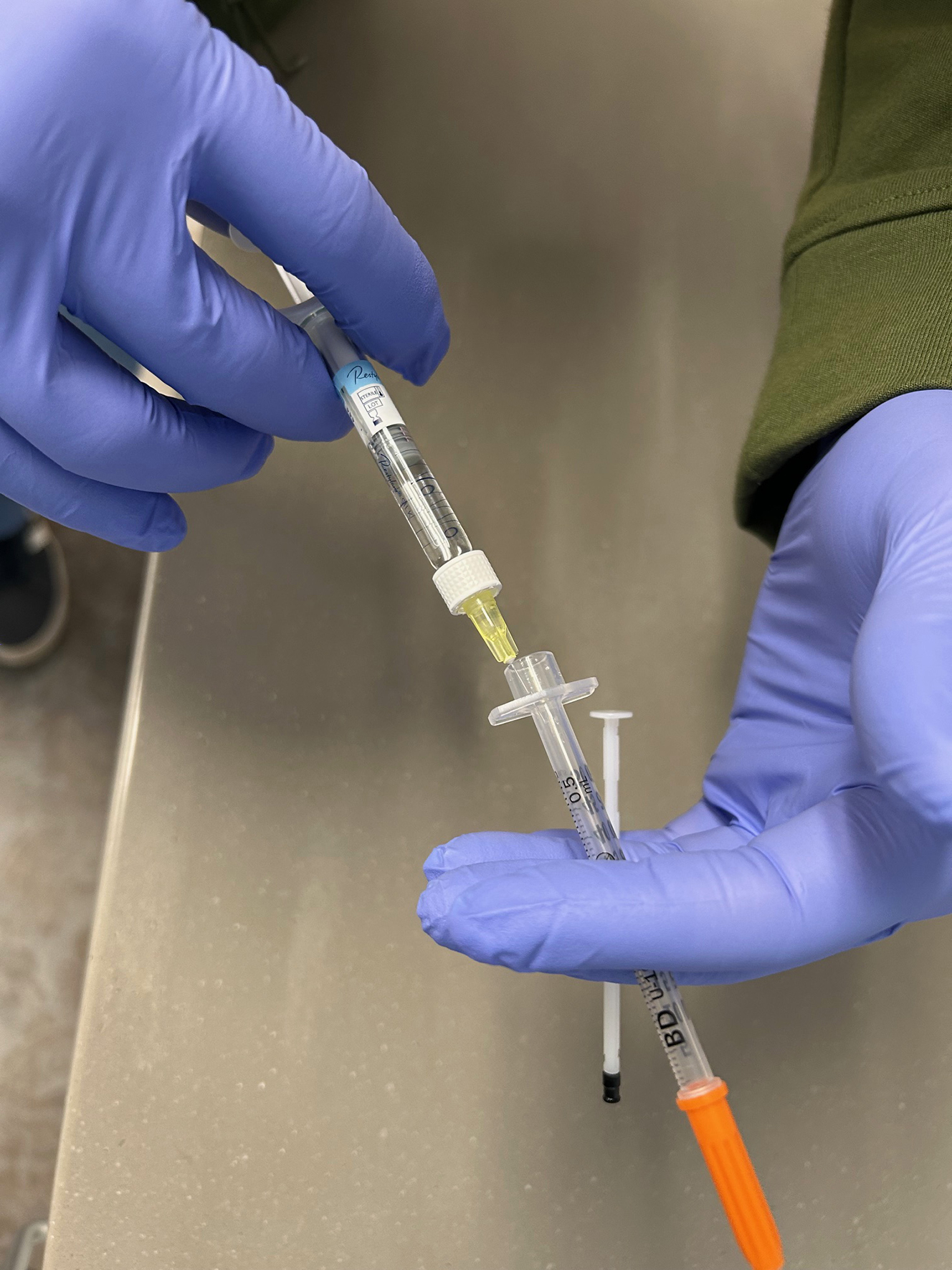

A linear threading technique with either a blunt or sharp needle tip with small boluses (<0.03 cc) is one option. Injection via cannula is another technique that is commonly used in the nose. The author’s preferred technique involves small bolus injections using back-filled insulin syringes. It is important to avoid larger gauge needles provided in the filler packaging for higher G′ fillers. These 27 G needles are ideal for deep injections in large areas of the face such as the cheeks but are much too large for NSR. Using smaller needles in theory helps achieve a higher level of safety and patient comfort. A 27 G needle increases the risk of vascular injury, allows for a higher extrusion force of the product, and places a larger bolus than smaller needles. The author backfills 0.5 cc 31 G insulin syringes with 0.1 to 0.2 cc of product in each syringe by removing the plunger and placing product into the syringe and replacing the plunger pushing the product to the front of the syringe ( Fig. 4 ). This technique allows smaller aliquots of filler to be used per injection with a much smaller extrusion force.

Product should be placed deep: either on the periosteum of the bone or perichondrium of the cartilage. In reality, perfect placement in these 2 planes may not always be realistic but the emphasis on deep injections is the key principle. Avoiding injections in the subdermal tissue will at least attempt to lower the risk of intravascular injury. Needle aspiration prior to injection may not be clinically useful in NSR as the small gauge of the needle may prevent backflow into the syringe and prevent the “flash” seen with larger needles. A 2 hand injection technique should be employed, using the nondominant hand to guide and stabilize the needle tip and then shape/smooth the tissue to the desired effect. Gentle massage of the site after injection can smoothen lumps, and touch ups should be offered after 2 weeks to allow for edema to decrease [ ]. Capillary refill (<2 seconds) should be tested on completion to insure no blanching.

There are numerous approaches to NSR depending on the overall desired esthetic outcome and deformity type/location. One proposed strategy to improve overall contour is to inject in the order of radix, rhinion, tip, and then supratip area [ ]. Another useful concept is replicating a known graft that exists in surgical rhinoplasty with filler instead to achieve similar results of augmentation and camouflage. A detailed discussion of injection technique by area is included later.

Radix

The radix, or root of the nose, refers to the upper bony portion of the nasal bones. Injection along the radix allows for treatment of a dorsal hump by moving the radix breakpoint superiorly and creating the effect of a straight bridge, similar to a radix graft in surgical rhinoplasty ( Fig. 5 ) [ ]. An important anatomic concept in this region is the relationship of the dorsal height to tip projection. When one raises the dorsal height with filler, it will provide the illusion of a shorter or less projected tip. This is ideal for most patients as creating a smaller appearing nose is a common esthetic goal. Prior to injection, lifting or manipulating of the skin of the radix can help simulate a straight dorsum to approximate the end goal. For extremely large dorsal humps, filling the radix to create a straight dorsum may raise the height past the point of esthetic balance. If this occurs, the nose tends to “blend” into the forehead without any distinct break point. This is unnatural and should be avoided. When this is anticipated, it is advised to discuss using NSR to “soften” the dorsal hump but not eliminate it entirely. If the patient’s desire is a completely straight dorsum, referral for a surgical rhinoplasty consultation is warranted.