CHAPTER 12 Fat Injections to the Breast

The Lipomodeling Technique

Summary/Key Points

Introduction

This approach has been considered since the very beginning of liposuction, particularly after the publication of the works of Illouz1 and Fournier.2 However, it remained controversial and was not widely used until the development of more precise tools and techniques. It was feared that autologous fat transfer would generate fat necrosis and calcifications which, at that time, were not readily assessable because of the limitations of existing imaging modalities.

The final blow came in 1987. After the presentation of a case by Bircoll,3 the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons recommended to stop using fat tissue injections for breast augmentation. The technique regained popularity after confirmation by Coleman4,5 that fat tissues could be transplanted safely provided that adequate care is given to the preparation and transfer of fat cells. In 1998, given the proven efficacy of fat transfer to the face for facial rejuvenation or post-surgery reconstruction, we developed a research program aimed at evaluating the efficacy of the procedure for thoracomammary reconstruction. We developed the technique named ‘lipomodeling’,6,7 then assessed its efficacy and tolerability in patients and demonstrated the absence of clinical or radiological signs of adverse effects.

History of the Technique and Progression of Ideas

First attempts

Fat grafting for breast plastic surgery has long been advocated by prominent surgeons. In 1895, at the German Congress of Surgery, Czerny described the first clinical case of breast reconstruction by transplantation of a giant lipoma of the lumbar region to the breast. Adipose cells were used to fill the void left in the breast after tumor resection in a patient with a fibroadenoma.8,9 Some surgeons thereafter performed breast reconstruction or augmentation using fascio-cutaneous flaps,10 gluteus fat implants,11 or local pedicle flaps.12 Injections of fat either directly into the breast1,2,13 or into previously inserted implants14 have also been reported. Some authors have even described the cases of women undergoing augmentation mammaplasty by cadaver fat allografts.15,16

Liposuction experiments published by Illouz1 contributed to the development of the technique and to the worldwide generalization of the concept. It became tempting to use autologous fatty tissues collected by liposuction for breast augmentation, as primarily done by Illouz. Similarly, in 1991, Fournier described the fat-grafting technique which he used only in patients who refused prostheses and who desired only moderate breast augmentation.2 The quantity of fat grafted to the patients was between 100 and 250 ml in each breast, injected in the retroglandular space, not in the mammary parenchyma.

The controversy

Fat grafting to the breasts has been highly controversial since the presentation by Bircoll, first in Bangkok in 1984, then at the California Society of Plastic Surgeons in 1985, of a case undergoing breast augmentation by injection of fat cells obtained by liposuction. The patient was a 20-year-old woman who requested a moderate augmentation of her breast while undergoing fat grafting to repair the damages caused by a dog bite. Bircoll3 considered the technique should only be used for women requesting moderate augmentation because of the potential risk of necrosis when grafting large quantities of fat. He reported the main advantages of the procedure: simplicity, absence of scar, early recovery, avoidance of prosthesis use and thereby of prosthesis-related complications, as well as the positive slimming impact at the site of fat removal. In April 1987,17 Bircoll reported the case of a patient undergoing bilateral fat grafting after unilateral reconstruction by transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM; improved aesthetic results and symmetry). The two papers triggered controversial reactions from the medical community18–21 who deplored that autologous fat injections in the breasts could generate microcalcifications and cysts, possibly interfering with the detection of early breast carcinoma. Bircoll argued22,23 that cancer-related calcifications and those consecutive to fat transplantation occur in different sites and have different radiological aspects, and therefore cannot be mistaken, and that breast reduction surgery also is responsible for microcalcifications, but the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons stated:

Ironically, in 1987, a retrospective study of the mammographic changes after breast reduction published in the same journal24 reported that calcifications were detectable in 50% of all mammograms at 2 years from surgery. The author insisted that in most cases these benign calcifications were easily distinguishable from cancer. Despite this high incidence and the risk for mammography abnormalities to interfere with cancer detection, there was no discussion of discontinuing breast reductions.

Progressive lifting of the taboo

The demonstration of the efficacy of fat transfer, based on atraumatic fat harvesting and injection, for facial rejuvenation and for the correction of facial deformities4,5 prompted us to adapt the technique to breast reconstruction. The contribution of fat grafting to the thorax and the breast for breast reconstruction has been one of our principal research topics over the past ten years. First, we used fat grafting along with autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction. This method, previously developed by our surgical unit,25–27 allowed satisfactory reconstruction in 70% of the cases. However, the other 30% resulted in insufficient breast volume and reduction of the contralateral breast was needed, or else insertion of a prosthesis; in this case, the procedure was no longer autologous and the patients suffered the drawbacks of prostheses (unnatural shape and texture, and obligation to change the prosthesis after a while). We started using fat grafting in breast cancer patients undergoing autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction who were at low risk of local recurrence. We named the technique ‘lipomodeling,’ from the Greek root lipo for fat, and the Latin word modello which means to give shape or volume, which is exactly the objective of this procedure. At first, only volunteer patients who agreed to undergo strict follow-up were operated on. Then, after the demonstration of the efficacy of the technique, we proposed it to almost all patients treated by latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction. Fat grafting provides them with optimal breast shape and texture as well as a natural cleavage. The study of mammography, computed tomography (CT)-scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings conducted in parallel28 demonstrated that the impact of lipomodeling on the patient’s images was far from negative. It was thus progressively extended to other indications of breast reconstruction, then to the correction of breast deformities, to the treatment of sequelae of conservative treatment and, more recently, to breast cosmetic surgery.

Our first presentations28,29 raised considerable controversy, similar to criticisms made in 1987. Point-by-point debate gradually won over the hostility of the clinical community and fat grafting has now become a standard procedure in breast reconstruction.7,30,31

Operative Technique6,7,31

Preparation

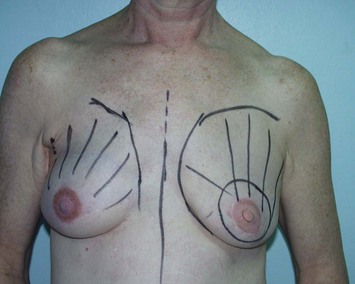

Careful clinical examination of the breast areas to be treated is required. They are identified and marked on the skin before the operation (Fig. 12.1). In addition to commonly used two-dimensional images, three-dimensional morphological images are taken and compared to evaluate the quantity of fat that should be grafted and estimate fat resorption.

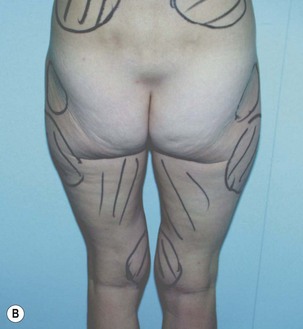

The various fatty areas in the patient’s body are examined to identify and locate natural fat deposits. Usually, the fat cells used for lipomodeling are those taken from the abdominal region. The patients are satisfied with the local thinning effect; and also, the procedure is easy for the surgeons since it is not necessary to change the patient’s position between collection and grafting. The second most frequent site for fat harvest is the trochanter (flabby thighs), and the inner side of the thighs and knees. Areas of fat harvest are visualized and marked with skin-marking pen (Fig. 12.2).

Fat harvesting

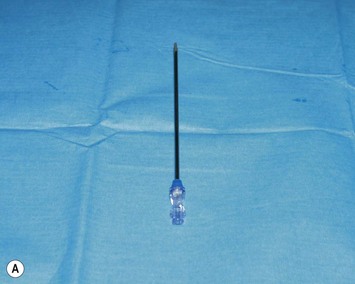

Recent work in the field has contributed to the standardization of the methods to be used for fat harvesting and grafting, and for the limitation of hazards at each step of the procedure. Only a strict observation of the rules at the different steps can ensure satisfactory median and long-term fat cell survival.4–79 Fat is harvested using a disposable cannula or a Coleman harvesting cannula. These blunt-tipped cannulas are inserted through 4 mm incisions made with a No. 15 blade, and directly attached to a 10 ml Luer-lock syringe. Fat cells are collected by moderate aspiration (Fig. 12.3) to minimize trauma on the adipocytes and improve the number of viable transplanted cells. The volume of fat aspirates must be enhanced to account for the cell loss incurred by centrifugation, refinement and transplantation.

Conditioning of the graft

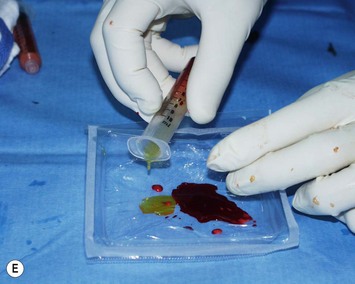

During fat harvesting, a surgical assistant prepares the cells for centrifugation by placing a screw cap on the extremity of each syringe (Fig. 12.4), then syringes are subjected to 3-minute centrifugation at 3200 rpm (Fig. 12.4). Six syringes can be processed at a time.

During centrifugation, harvested fat cells are separated into three layers (Fig. 12.4C):

Careful planning is necessary to ensure efficient and rapid preparation of the fat graft. Fat cells are transferred from one syringe to the other using a three-way stopcock, then collected into 10 ml fractions (Fig. 12.4F).

Placement of the fat graft

When all fat samples have been processed, a number of 10 ml syringes of purified fat aspirates are available. The fat is then transferred directly from the 10 ml syringes to the breast area by adapting specific disposable cannulas of 2 mm diameter. These cannulas (Fig. 12.5A) are slightly longer and more resistant than those used for fat grafting to the face because higher mechanical constraints are associated with injection of fat into more solid and more fibrous tissues.

Incisions to the breast are performed using a 17 gauge needle knife (Fig. 12.5B). These small incisions allow for the passage of the cannula while limiting the impact of scarring and preserving the cosmetic results of the procedure which becomes almost invisible with time. Multiple small incisions, positioned to allow accurate placement of graft tunnels in different radial directions are required to ensure correct shaping.

It is recommended to inject the fat in small spaghetti strips (Fig. 12.5C), in multiple layers and multiple directions, from deep to superficial tissues (Fig. 12.5D), following a three-dimensional grid pattern. A good spatial representation of the area is required to avoid injecting large fat clumps potentially responsible for fat cell necrosis. On the contrary, each aliquot must be injected in a well-vascularized area, at a distance from other injection sites, and under low pressure (while gently pulling the cannula back).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree