Facial aging involves changes in the craniofacial skeleton, soft tissues, smile, and teeth. Orthodontic treatment can address these changes by improving directly dental and smile esthetics, and skeletal alignment and indirectly the surrounding soft issues. The guidelines for orthodontic management of the aged face aim at increasing lower face height, and volumizing the dentoalveolar part of the face. Combining orthodontics with other medical disciplines can yield synergistic effects, rejuvenating faces and improving overall well-being. Case studies demonstrate the positive impact of orthodontic treatment on facial esthetics.

Key points

- •

Age-related changes to facial bones, fat, muscles, ligaments, skin, teeth, and smile.

- •

Orthodontics promotes the rejuvenation of faces affecting directly the dentoalveolar bone and the teeth, and indirectly the rest of the facial tissues.

- •

Orthodontic treatment planning guidelines for rejuvenation.

- •

Self-esteem and confidence increase.

- •

Synergistic effect of orthodontics and other medical cosmetic interventions.

Introduction

Facial aging is a process that is influenced by numerous environmental factors [ ], as well as intrinsic (genetic) factors [ ] affecting the different components of the facial anatomy such as the skin, fat, muscles, ligaments, skeleton, and the teeth with the surrounding dentoalveolar bone. Seminal orthodontic research has contributed to the understanding of the alterations occurring at the craniofacial complex associated with postmaturation and aging [ ], and newer evidence on dental [ ] and lip changes is continuously emerging [ ]. Despite the broad belief that the craniofacial skeleton is expanding throughout life in general, it has been well documented that specific areas of it undergo resorption impacting the aging pattern [ ], emphasizing the stigmata of the aging face.

Aging and the reversal or amelioration of its consequences had led to an increase in the number of minimally invasive cosmetic procedures to more than 25 million in the year 2023 in the United States alone. It is the elder Generation X and Younger Boomers who dominate the facial enhancement procedures category [ ]. Adult patients seeking orthodontic treatment have increased from 15% to 35% of new case starts in orthodontic practices, with a rising tendency [ ]. Orthodontic treatment has anecdotally been perceived to service the demand for addressing problems relating to dental esthetics but adults have often complex treatment needs. Since the skeleton of the face has a significant effect on an individual’s appearance, it should be expected that elderly patient satisfaction and treatment uptake could be enhanced if facial rejuvenation can be among the anticipated outcomes of treatment. To rejuvenate the aging face effectively, it is necessary to understand the dynamic aging processes and the imbalances between these components that lead to the characteristics of the aged face [ ]. The under-projection of the elderly facial bones if overlooked and managed incorrectly with conventional facelift soft-tissue techniques may lead to unpleasant esthetic results [ ]. It would be beneficial thus for the elderly individuals if the aging process could be managed from both the bone and soft-tissue aspects with the minimum invasive techniques, providing the maximum in esthetics.

The aims of this article are (a) to briefly describe the skeletal changes to the maxilla, mandible, soft tissues, and smile/teeth induced by aging, and (b) present the effect orthodontics may have on elderly faces, rejuvenating them at the dentoalveolar/skeletal and the “facial mask” level, altering the initial perception of a patient’s cosmetic needs and possibly augment the result of any cosmetic procedure(s) that may follow. If these aging aspects as well as those associated with the smile are addressed prior to any cosmetic treatment, the final approach may need to be significantly modified [ ].

Bone changes of the midface and the mandible

There is change in the relative dynamics between bone resorption and expansion in the aging craniofacial skeleton and the process is not purely the atrophy of the bone. Computed tomography images of the face have shown that aging reduces the height of the maxilla relatively to the orbit which had increased from infancy to youth and that further actual decrease in vertical maxillary height in the medial plane occurs secondary to the normal skeletal remodeling in the dentate individuals [ ]. Clockwise rotation and recession of the maxilla has been repeatedly observed in various studies [ ] which appear to undermine midfacial support and projection, and the findings seem to be more profound in women than they are in men [ , ]. Also, the rate of facial aging tends to increase after the age of 50 with a higher pace for women [ ]. In general, the maxillary skeleton exhibits primarily signs of retrusion and deterioration [ , ].

The mandible can be considered the pillar supporting the lower part of the face. The shape of the mandible changes, becoming less convex with age, as some areas continue to grow faster than others according to the principle of differential growth [ ]. Ramus height, mandibular body height, and mandibular body length decrease significantly with age for both genders, whereas the mandibular angle increases significantly for both genders with increasing age, the processes being mainly those of contraction [ ]. The aging process of the mandible often involves resorption of bone in the chin region [ ]. The presence of the dentition is of predominant importance in mandibular morphology [ , ], and the vertical dimension [ ] which plays a significant role in facial esthetics. In general, there is an appreciable reduction in facial height, which is mainly due to changes in the maxilla and mandible, and a modest increase in facial width and depth [ ]. Even with bony changes of small magnitude, the effects can be dramatic through amplification via the overlying structures [ ].

Soft tissue changes

The skeletal changes described earlier when combined with the changes in soft tissues lead to the characteristic appearance of the aged face. The main external factors responsible for skin aging are ultraviolet radiation, pollution, and smoking while intrinsic aging also contributes to the appearance of fine rhytids and skin laxity [ ]. With intrinsic aging, the skin thins and weakens as the dermis atrophies from changes related to deterioration of these components. The rate of collagen breakdown increases, whereas the rate of collagen synthesis decreases [ ]. Volumetric changes and gravitational descent of the facial fat are considered responsible for some of the changes observed during aging [ ]. It is the redistribution and demarcation of fat that gives the senile face an unbalanced appearance [ ]. Permanent muscle contractures, loss of mass volume, and changes in physiology are also accountable for facial wrinkles and volume loss that signify aging [ ]. Although muscles may weaken with age, their relative pull is greater on the less resistant tissues and dermis and can result in hyperdynamic expressions [ ]. The zygomatic, the orbital retaining, and the mandibular retaining ligaments are the most affected by aging and are weakened, which in combination with the bony changes affecting the point of origin of all the facial ligaments promote the appearance of the facial sagging [ ].

Smile/teeth changes

The maxillary anterior teeth are key elements for smile esthetics, and the display of the maxillary incisors at rest and on smile is a characteristic of youthful appearance [ ]. The upper lip elongation is a continuous process and in the third and fourth decades of life, after growth of the craniofacial skeleton is minimal, elongation of the upper lip exceeds vertical growth of the face in different populations [ , ]. As age advances, the loss of resting muscle tone and increased flaccidity and redundancy contribute more in lowering of the smile height than the decreased muscle’s ability to create a smile [ , ]. Dynamic smile analysis showed that as a person ages, the smile gets narrower vertically and wider transversely. The result is a significant decrease in incisor display at rest, speech, and smile, along with a greater display of mandibular incisors [ , , ]. It should be noted that crowding in the lower anterior area increases, especially in females, with age [ ] making the image less esthetically pleasing. Natsumeda and colleagues [ ] followed a group of subjects with normal occlusions for 5 decades and noticed significant changes in proportions (due to shortening of crown height), color, angulation, and gingival step between central and lateral incisor which are all factors impairing dental and smile esthetics, and attractiveness. Faces with more white dentition are perceived to be younger across all age groups and gender of judges [ ]. Elderly adults may have fewer teeth, edentulous spaces, failing restorations, teeth with uncertain prognosis, more wear and abrasion, more artificial crowns, advanced periodontal tissue destruction, pronounced gingival recessions, higher frequency of uneven gingival margins due to combinations of supraeruption and wear, and a greater need for implants, preprosthetic orthodontic treatment, and orthodontic molar uprighting [ ] all of which make the restoring of the dentition more challenging.

There is a close link between physical appearance and self-esteem, family life, social attractiveness, and professional life. Attractiveness would therefore seem to make an essential contribution to an individual’s self-fulfillment and Quality of Life [ , ]. Facial tissues change over time, and the orthodontist’s training is to understand the principles of dental and skeletal development, maturation, and aging in addition to the many other facets of dental practice. Given the substantial variations in the substrate, the treatment planning for adults may well deviate from that for younger individuals, for whom conventional orthodontic protocols are more readily applicable. Orthodontic treatment has been shown that it cannot only correct an existing or acquired malocclusion and provide a beautiful smile but it can also contribute to the rejuvenation of an elderly face when properly planned [ ]. Guidelines for orthodontic management of the aged face have been developed and cases treated according to these guidelines are presented.

Rejuvenation and orthodontics—guidelines

- •

When facial rejuvenation is a treatment objective, comprehensive facial evaluation should be prioritized, and a sound diagnosis of macro-esthetic needs (esthetics of the face), should be made [ ].

- •

Posterior displacement of the skeletal elements inferior to the orbit, accompanied by bone loss at the pyriform process, is associated with a deepening of the nasolabial fold. This suggests that maintaining the maxilla-mandibular skeleton in a forward position can be esthetically advantageous.

- •

As the height of the upper part of the lower face increases with aging, the lower part should also be increased to maintain harmony and balance.

- •

A decrease in the maxillary and mandibular body heights combined with loss of tooth structure also supports methods to increase lower face height. In a periodontally healthy environment, creating a posterior open bite at the start of treatment and promoting eruption of the posterior teeth into the space created could prove advantageous for the elderly patient.

- •

A decrease in maxillary anterior teeth exposure may be managed by combining the above with clockwise rotation of the occlusal plane; any deep bite correction required should be carried to the lower teeth. Disarticulating the occlusion at the most posterior teeth in the arch and combining extrusion of upper and lower teeth anterior to it can promote rotation around this artificially created fulcrum point. Once the desired rotation and vertical height are established and the overjet has been improved (clockwise rotation of the occlusal plane may also benefit the decrease of the overjet), the disarticulation point can be transferred anteriorly, behind the central incisors where it may act as a stable determinant of the final anterior lower face height.

- •

An increase in the mandibular width with age that overthrows the width-to-height [W/H] facial ratio can be masked, and youthful looking W/H proportions could be restored by increasing lower face height, which is in agreement with the previous. If mesial movement of molars and lingual movement of first premolars and canines is present in elderly patients [ ], uprighting and expansion of the lingually tipped teeth should be performed preferably.

- •

The square appearance of older faces due to facial fat descent and increase in submalar fullness may be also harmonized by increasing the lower face height.

- •

Individuals who present cephalometric characteristics of “long-face” could still require elongation of the lower face height in later adulthood.

- •

Dentoalveolar transverse development is strongly recommended—when it can be safely accomplished—since it may enhance the support of the overlying loose and shrunk soft tissues, and may also compensate for lost fat, thus restoring “youthful” contours.

- •

Dentoalveolar posteroanterior development could also improve the skin appearance by stretching the perioral wrinkles.

Case 1

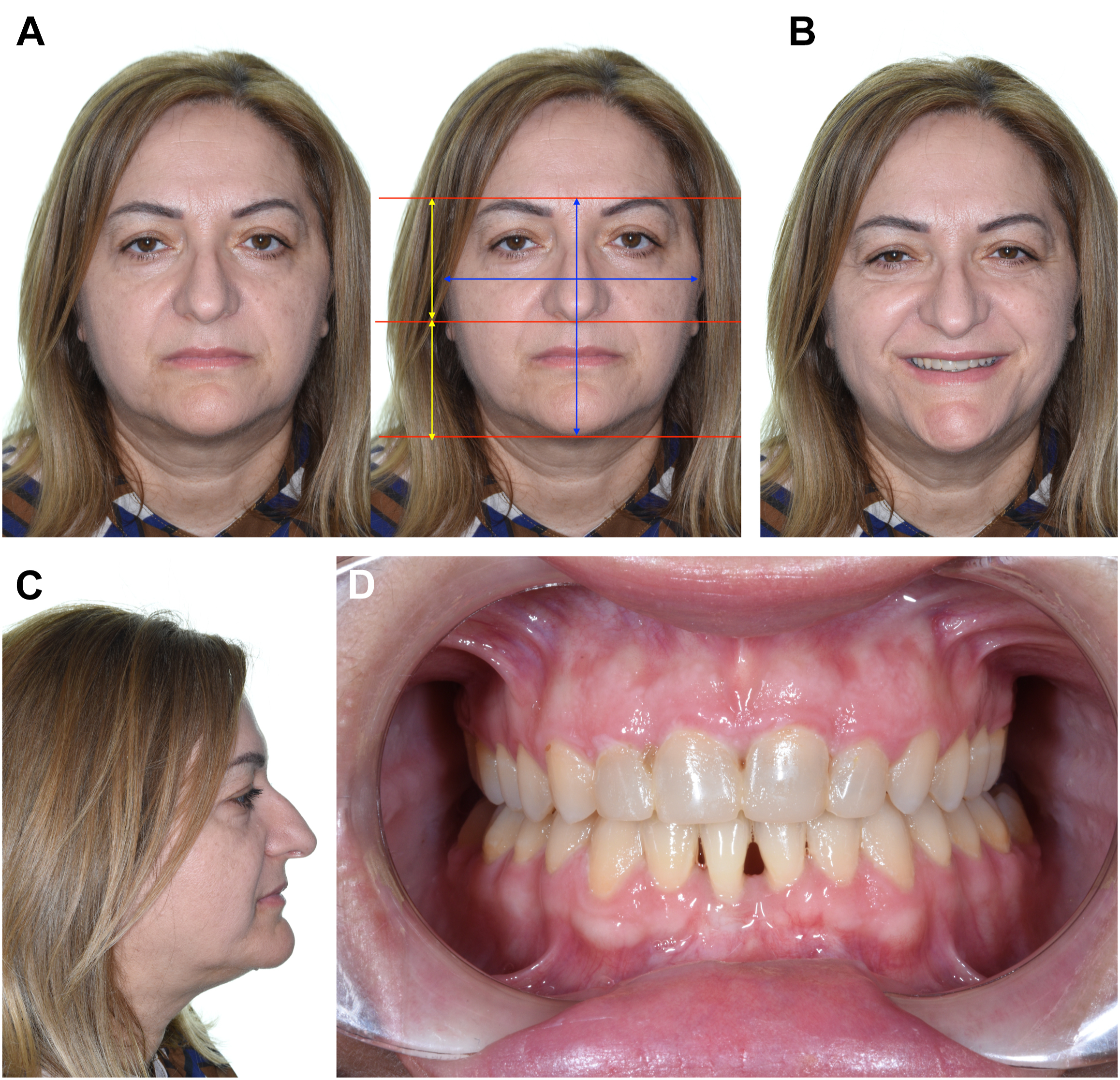

A 54-year-old female who needed restoring of her worn upper anterior teeth ( Fig. 1 D ) was referred by her dentist to assess the possible benefits from an orthodontic intervention. However, a comprehensive macro-esthetics evaluation revealed several facial abnormalities: severely short lower face height ( Fig. 1 A, right), distorted facial W/H ratio (W/H ≅ 1.13), thin and collapsed lips, deep nasolabial folds, prominent jowls ( Fig. 1 A, left), concave profile with an upward rotated chin ( Fig. 1 B), a blunt cervico-mandibular angle, and no teeth exposure upon smiling ( Fig. 1 C). The treatment deviated from the simple rearrangement of the teeth (which were relatively straight) and encompassed the normalization of as many of the impaired facial characteristics as possible. A new vertical dimension was immediately established by applying composite on the posterior teeth (as described above) resulting in a more harmonious facial appearance and allowing the unfolding of the depressed lips ( Fig. 1 E), and created space anteriorly for the temporary reconstruction of the anterior teeth with composite resin ( Fig. 1 F).

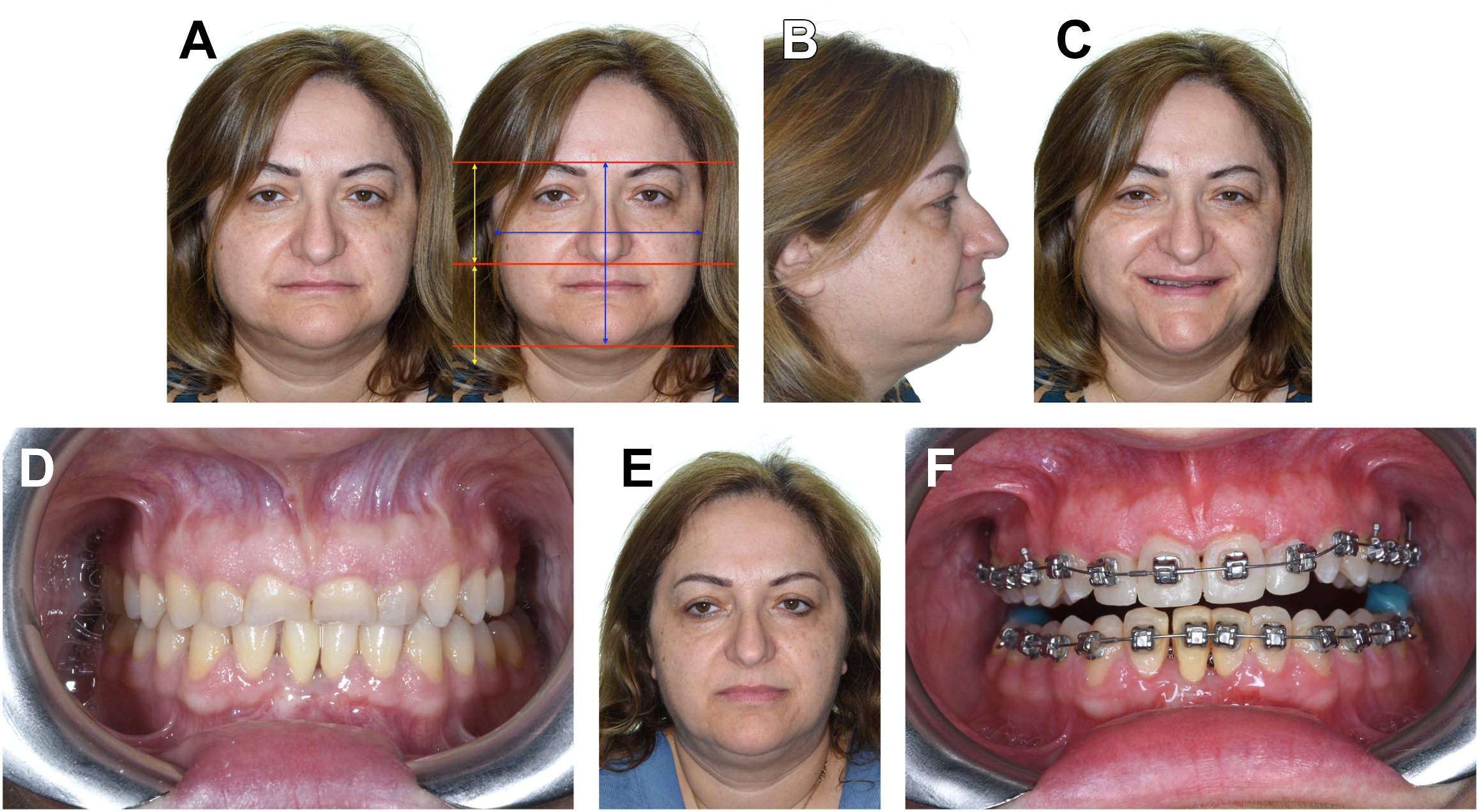

The posttreatment photographs demonstrate increased lower face height and improved facial W/H ratio (W/H ≅ 1.0) ( Fig. 2 A , right), increased upper lip length and nicely unfolded lips with normalized volume, softer nasolabial folds ( Fig. 2 A, left), straightened profile ( Fig. 2 C), adequate tooth exposure when smiling ( Fig. 2 B), and corrected occlusal relationships with temporary restorations on the anterior teeth ( Fig. 2 D). Any additional cosmetic medical intervention could have a synergistic effect, resulting in a multiplicative enhancement of the esthetic benefits for the patient.