Facial rashes

Paul Farrant MRCP

Russell Emerson MD, MRCP

Introduction

Facial rashes cause cosmetic embarrassment to patients and are an important source of anxiety. The face is involved in many different diseases because it contains numerous sebaceous glands and is constantly exposed to the environment. This chapter describes the common dermatological diseases and an approach to differentiating them from each other.

History

It is important to take a thorough history of the presenting skin complaint and exposure to external factors including ultraviolet light (UV), cosmetic products, prescribed topical creams, and systemic therapies. This should include a medical history and enquiry about other medical symptoms including muscle weakness, joint pains, and past history of skin problems. Table 6.1 lists the clinical features of common facial rashes.

Scale: rashes with associated scale suggest psoriasis (silvery-white), seborrhoeic dermatitis (greasy, yellow), eczema, contact dermatitis, or possibly a fungal infection.

Pustules and papules: acne, rosacea, perioral dermatitis, folliculitis and pseudo folliculitis barbae. Multiple small papules on the cheeks are seen in tuberous sclerosis and polymorphic light eruption following UV exposure.

Vesicles/milia/cysts: vesicles are seen with herpetic infections. Milia are common but may be a feature of porphyria. Cysts are common on the face and can occur in isolation (epidermoid, pilar) or as part of an acneiform eruption.

Swelling: periorbital swelling is seen with angio-oedema (urticaria), dermatomyositis, and rosacea. Swelling and redness of one cheek are seen with erysipelas. Acute contact dermatitis often causes localized itching and swelling which becomes dry or scaly, whereas urticaria/angio-oedema does not.

Pigmentation: macular pigmentation on the cheeks is suggestive of melasma. The face is also a common site for simple lentigo, lentigo maligna, and seborrhoeic keratoses.

Atrophy/scarring: discoid lupus is associated with scarring. Atrophoderma vermiculatum, a facial variant of keratosis pilaris, causes atrophy over the cheeks.

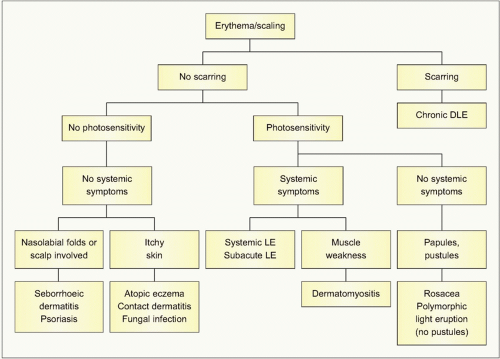

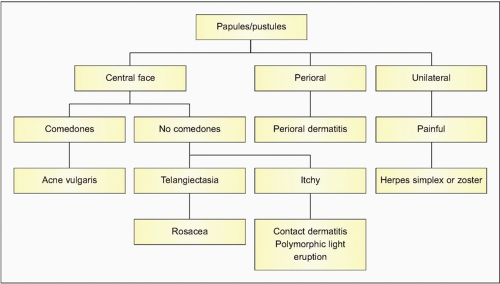

A stepwise approach to the management of patients with erythema/scaling and papules/pustules is seen in 6.1 and 6.2, respectively.

Table 6.1 Clinical features of facial rashes | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acne

Introduction

Acne is a disorder affecting the pilosebaceous unit associated with excess grease production of the skin, keratinization of the opening of the hair follicle, and inflammation due to bacterial infection with Propionibacterium acnes that may result in scarring.

Clinical presentation

Acne typically presents with open comedones (black heads), closed comedones (white heads), papules, pustules, and cystic lesions (6.3). The face, upper chest, and upper back are most commonly affected. Macrocomedones and scarring (both pitted and hypertrophic) are also features. A particular variant, acne excoriée, is characterized by marked excoriations on the face and is typically seen in young women (6.4).

Histopathology

Perifollicular inflammation with a predominance of neutrophils is seen. The hair follicles are often dilated, and filled with keratin. Rupture of the follicles can result in a foreign body reaction.

Differential diagnosis

Folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis can all mimic acne on the face. Acne-like conditions can also be precipitated by drugs (e.g. antiepileptics), topical and oral corticosteroids, oils applied to the hair line (pomade acne), and exposure to various chemicals (e.g. chloracne).

Management

Most acne will clear spontaneously by the mid twenties. Mild acne can be managed by topical agents, applied daily for 3-6 months. These include benzoyl peroxide (first line, good for noninflammatory acne), topical antibiotics (erythromycin, clindamycin), and topical retinoid related drugs (tretinoin and adapalene). Combinations of these agents can also be used, for example benzoyl peroxide in the morning and a retinoid in the evening.

Moderate acne is best managed with systemic antibiotics in addition to topical agents. These again require 3-6 months of treatment to achieve long-term clearance. These include oxytetracycline, lymecycline, erythromycin, and trimethoprim.

For unresponsive cases or severe acne associated with scarring, specialist referral is indicated. Such patients may require a 4-6 month course of oral isotretinoin. This achieves clearance in 85% of patients. Frequent side-effects include dryness of the lips, mucous membranes, and skin. It should be avoided in pregnancy and patients may require monitoring of their liver function and lipids. Any change in mood or tendency to depression during treatment should lead to cessation of therapy.

Perioral dermatitis

Introduction

Perioral dermatitis typically affects young women in the 20-35-year-old age group. It is a variant of rosacea and may be precipitated by inappropriate use of moderate/potent topical corticosteroids.

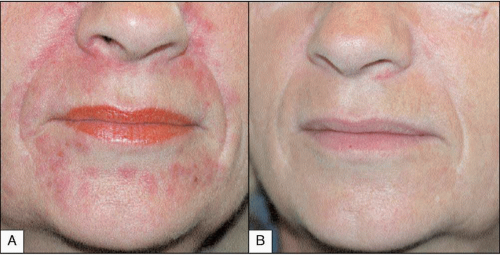

Clinical presentation

It is characterized by small erythematous papules around the mouth and chin (6.5A). The area immediately adjacent to the vermillion border is usually spared. There may also be periorbital involvement. Comedones are not a feature.

Differential diagnosis

Acne vulgaris, steroid acne, rosacea, and seborrhoeic dermatitis are the main differentials.

Management

Patients should be advised to stop the application of topical corticosteroids and placed on a 2-4 month course of oral tetracycline antibiotics (6.5B). Topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus may also be beneficial for flares.

Rosacea

Introduction

Rosacea is a common cause of facial redness in the 25-55-year-old age group, especially women.

Clinical presentation

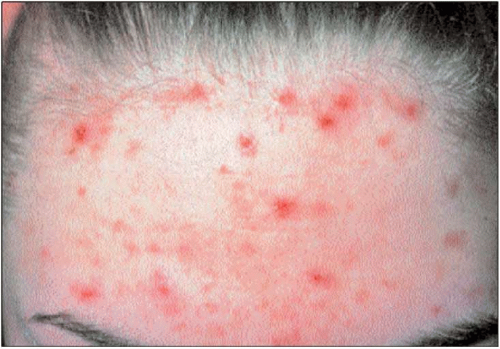

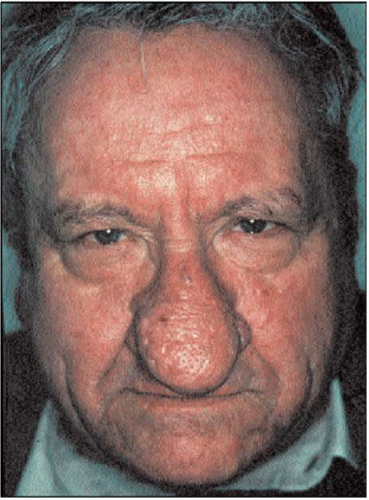

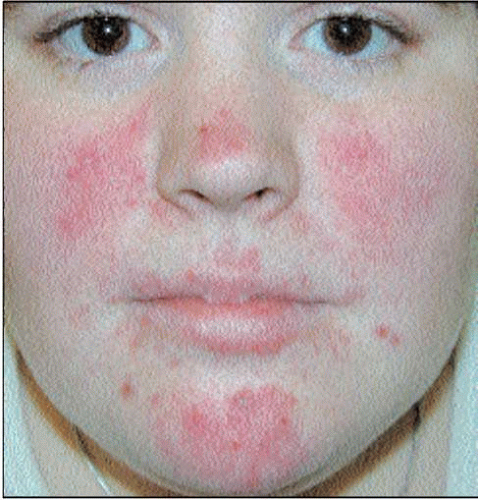

Many patients have a history of flushing exacerbated by trigger factors including spicy foods, temperature changes, and alcohol. Facial redness typically occurs with small papules and occasional pustules (6.6, 6.7). The inflammatory changes typically affect the cheeks and nasolabial folds. Fixed redness may develop associated with superficial blood vessels (telangiectasia) and rarely sebaceous hyperplasia leads to an enlarged nose (rhinophyma) (6.8). Up to 15% of patients may have associated eye involvement presenting as conjunctivitis, keratitis, blepharitis, and cyst formation along the eyelid margin. Comedones are typically absent in rosacea.

6.6 Papular lesions on the cheeks, nose, and chin with no evidence of comedones is typical of rosacea. |

Histopathology

A mixed lympho-histiocytic perifollicular infiltrate may be present. In addition, there may be a perivascular infiltrate or granulomatous response. These changes are nonspecific. There may also be vascular dilatation, solar elastosis, and sebaceous gland hyperplasia indicating solar damage.

Differential diagnosis

Rosacea should always be suspected in patients with facial redness and papules. Other causes of flushing and erythema include eczema, seborrhoeic dermatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and the carcinoid syndrome.

Management

Patients should avoid trigger factors. Mild cases can be managed with topical metronidazole gel. More severe cases (6.7) require courses of systemic tetracyclines for 2-4 months. Many patients experience disease relapses and patients should be informed that it might be a chronic condition. Severe cases may need a specialist opinion and low-dose oral isotretinoin can be beneficial. Patients with rhinophyma and telangiectasia may benefit from skin surgery and laser therapy, respectively.

Atopic eczema

Introduction

Facial eczema commonly affects adults with severe eczema and can be a presenting feature of allergic contact dermatitis.

Clinical presentation

In infants the cheeks are a common site to be involved, with an ill-defined, red, scaling rash that is symmetrical. Episodes of infection are common and weeping and crusting are both common in this context. In adults, eczema can be either generalized (6.9, 6.10), or more localized to specific areas such as the skin around the eyes and mouth. Lichenification of the skin may be present around the eyes (6.11).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree